полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 3

Audubon states that Mr. Ward, his assistant, found this species breeding on the Santee River early in the month of March. Their nests were said to be placed on low trees near the margin of the river, and to be not unlike those of the common Crow, but without the substantial lining of its nests. Mr. Ward also mentioned seeing them flying over the cane-brakes, in pursuit of large insects, in the manner of the Mississippi Kite, and finding the birds very shy.

In Southern Illinois it has been known to occur as far north as Mount Carmel, where Mr. Ridgway saw a pair in July, flying about among the dead trees bordering a lagoon near the Wabash River.

Mr. Audubon, in his visit to Texas, saw several of these birds flying at a small elevation over the large marshes, and coursing in search of its prey in the manner of the common Marsh Harrier.

Dr. Heermann found the extensive marshes of Suisun, Napa, and Sacramento Valleys the favorite resorts of these birds, especially during the winter, and there they seemed to find a plentiful supply of insects and mice. They ranged over their feeding-grounds in small flocks from a single pair up to six or seven. He fell in with an isolated couple in the mountains between Elizabeth Lake and Williamson’s Pass, hovering over a small freshwater marsh. In July and August the young were quite abundant, from which Dr. Heermann inferred that it does not migrate for the purposes of incubation. Dr. Gambel, who procured his specimens at the Mission of St. John, near Monterey, describes it as flying low and circling over the plains in the manner of a Circus, and as feeding on the small birds. It was easy of approach when perched on trees, and uttered a loud shrill cry when wounded, and fought viciously.

Lieutenant Gilliss, who found them in Chile, describes the nest as composed of small sticks, and states that the number of the eggs is from four to six, and that they are of a dirty yellowish-white with brownish spots. The common name of this Hawk in Chile is Bailarin (from the verb bailar, to dance or balance), from the graceful and easy manner in which it seems almost to float upward or to sink in the air.

An egg of this species, in the collection of the Boston Society of Natural History, measures 1.64 inches in length by 1.48 in breadth. In shape it is very nearly spherical, and equally obtuse at either end. The ground-color, though nowhere very distinctly apparent, appears to be of a dull white, strongly tinged with a reddish hue. Distributed over the entire egg are broad deep flashes of a dark mahogany-brown, intermingled with others of a similar color, but lighter in shading. These cover the egg more or less completely, in the greater portion of its surface. This egg was taken near Fort Arbuckle, Indian Territory, May 9, 1861, by J. H. Clark, Esq., and sent to the Smithsonian Institution.

Genus ICTINIA, Vieillot

Ictinia, Vieill. 1816. (Type, Falco mississippiensis, Wilson.)

Nertus, Boie, 1826. (Type, Falco plumbea, Gmelin.)

Pœcilopteryx, Kaup, 1844. (Same type.)

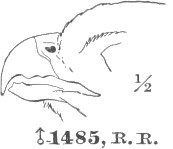

♂ 1485, r. r. ½

Ictinia mississippiensis.

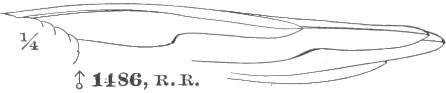

♂ 1486, r. r. ¼

Ictinia mississippiensis.

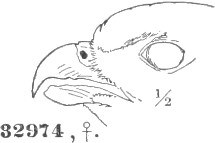

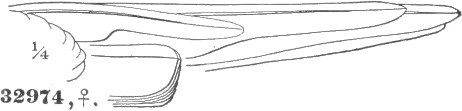

32974, ♀. ½

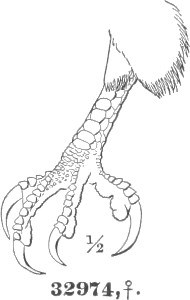

32974, ♀. ½

32974, ♀. ¼

I. plumbea.

Gen. Char. Form falcon-like; the neck short, wings long, and pointed, the primaries and rectrices strong and stiff, and the organization robust. Bill short and deep, the commissure irregularly toothed, and notched; gonys very convex, ascending terminally; cere narrow; nostril very small, nearly circular; feet small, but robust; tarsus about equal to middle toe, with a distinct frontal series of broad transverse scutellæ; claws rather short, but strongly curved, slightly grooved beneath, their edges sharp. Third quill longest; first of variable proportion with the rest. Tail moderate, the feathers wide, broader terminally, and emarginated.

This genus is peculiar to America, the two most closely related genera being Elanus on the one hand and Harpagus on the other. Its species belong to the tropical and subtropical regions, one of them (I. plumbea) generally distributed throughout the intertropical portions, the other (I. mississippiensis) peculiar to Mexico and the southern United States.

In their habits, they are very aerial, like the genus Nauclerus, sailing for the greater time in broad circles overhead, occasionally performing graceful evolutions as they gyrate about. Like Nauclerus, they are also partially gregarious, and, like it, feed chiefly on insects and small reptiles, which they eat while flying.

SpeciesCommon Characters. Adult. Uniform plumbeous, becoming lighter (whitish) on the head, and darker (blackish) on the primaries and tail. Inner webs of primaries with more or less rufous. Young. Beneath whitish, striped longitudinally with brownish; above much variegated: tail with several narrow whitish bands.

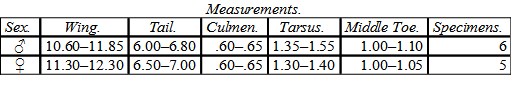

1. I. mississippiensis. Adult. Wings lighter than the tail, the secondaries hoary whitish; inner webs of primaries with only obscure spots of rufous, the outer webs with a very obscure stripe of the same. Tail wholly black. Young. Stripes beneath reddish-umber; lower tail-coverts with longitudinal shaft-streaks of the same. Second to third quills longest; first shorter than seventh and longer than sixth. Wing, 10.60–12.30; tail, 6.00–7.00; culmen, .60–.65; tarsus, 1.30–1.55; middle toe, 1.00–1.10. Hab. Prairies and savannas of the southern United States and Northern Mexico, from Wisconsin and Georgia to Mirador.

2. I. plumbea.75 Adult. Wing concolor with the tail, the secondaries black; inner webs of the primaries almost wholly rufous; outer webs with only a trace of rufous. Tail with about three bands of pure white, formed by transverse spots on the inner webs. Young. Stripes beneath brownish-black; lower tail-coverts transversely spotted with the same; upper parts darker. Third quill longest; first shorter or longer than the seventh. Tail more nearly square. Wing, 10.50–12.20; tail, 5.60–6.80; culmen, .62–.70; tarsus, 1.15–1.50; middle toe, 1.00–1.05. Hab. Tropical America, from Paraguay to Southern Mexico.

Ictinia mississippiensis (Wilson)MISSISSIPPI KITE; BLUE KITEFalco mississippiensis, Wils. Am. Orn. pl. 25, f. 1, 1808.—Lath. Gen. Hist. I, 275.—James. (Wils.) Am. Orn. I, 72, 1831. Nertus mississippiensis, Boie, Isis, 1828, 314. Milvus mississippiensis, Cuv. Règ. An. (ed. 2), I, 335, 1829. Ictinia mississippiensis, Gray, Gen. B. fol. sp. 2; List B. Brit. Mus. p. 48, 1844; Gen. & Sub-Gen. Brit. Mus. p. 6, 1855.—Cass. B. Cal. & Tex. p. 106, 1854.—Kaup, Ueb. Falk. Mus. Senck. p. 258, 1845; Monog. Falc. Cont. Orn. 1850, p. 57.—Strickl. Orn. Syn. I, 140, 1855.—Brewer, Oölogy, I, 1857, 41.—Coues, Prod. Orn. Ariz. p. 13, 1866.—Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 327 (Texas).—Gray, Hand List, I, 28, 1869. Falco plumbeus, Aud. Orn. Biog. II, 108, pl. cxvii; V, p. 374, 1831. Ictinia plumbea, Bonap. Eur. & N. Am. B. p. 4, 1838; Ann. N. Y. Lyc. II, 30; Isis, 1832, p. 1137.—Jard. (Wils.) Am. Orn. I, 368, pl. 25, f. 1, 1832.—Brew. (Wils.) Synop. 685, 1852.—Aud. Synop. B. Am. p. 14, 1839.—Woodh. (Sitgr.) Exp. Zuñi & Colorad. p. 61, 1853.—Nutt. Man. 92, 1833.

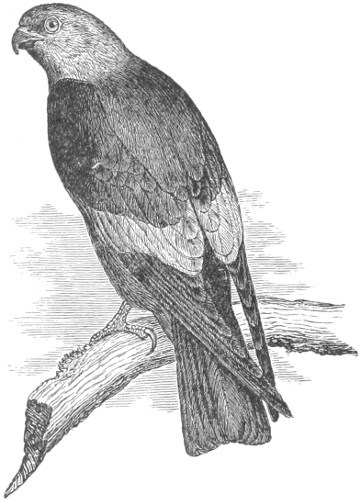

Sp. Char. Adult male (No. 1,486, Coll. R. Ridgway, Richland Co., Ill., August 19, 1871). Head, neck, secondaries, and entire lower parts plumbeous-ash, becoming, by a gradual transition, lighter on the head and secondaries, where the shade is pale cinereous; the head anteriorly, and the tips of the secondaries, being silvery-white. Lores and eyelids black. Rest of the plumage dark plumbeous, approaching plumbeous-black on the lesser wing-coverts, primaries, and upper tail-coverts, the tail being nearly pure black. Primaries with an indistinct narrow concealed stripe of chestnut-rufous on the outer webs, and larger spots of the same on the inner webs; feathers of the head, neck, and lower parts abruptly pure white beneath the surface, this showing in partially exposed spots on the pectoral region and crissum. Scapulars also with large concealed white spots. Shafts of primaries and tail-feathers black on both sides. Wing-formula, 3, 2–4–5–6, 1. First primary angularly, the second concavely, emarginated. Tail emarginated, lateral feather longest; depth of fork, .40. Wing, 11.75; tail, 6.80; culmen, .63; tarsus, 1.20; middle toe, 1.15.

Adult female (No. 1,487, Coll. Ridgway, Richland Co., Ill., August 19, 1871). Similar to the male, but head and secondaries decidedly darker, hardly approaching light ash; scarcely any trace of rufous on the primaries, none at all on outer webs; shafts of tail-feathers white on under side. Wing, 11.80; tail, 7.25. Bill, cere, eyelids, and interior of mouth, deep black; iris deep lake-red; rictus orange-red; tarsi and toes pinkish orange-red; lower part of tarsus and large scutellæ of toes dusky. (Notes from fresh specimens, the ones above described.)

Immature male (transition plumage; 1,488, Coll. Ridgway, Richland Co., Ill., August 21, 1871.) Similar to the adult female, but the white spots on basal portion of pectoral and crissal feathers distinctly exposed; secondaries not lighter than rest of the wing. Tail-feathers with angular white spots extending quite across the inner webs, producing three distinct transverse bands when viewed from below. Inner web of outer primary mostly white anterior to the emargination. Wing, 10.50; tail, 6.25. Color of bill, etc., as in the adult, but interior of mouth whitish, and the iris less pure carmine.

Immature female (Coll. Philadelphia Academy, Red Fork of the Arkansas, 1850; Dr. Woodhouse). Similar to the last. Wing, 11.10; tail, 6.31.

Young female (first plumage; Coll. Philadelphia Academy, North Fork Canadian River, September 19, 1851; Dr. Woodhouse). Head, neck, and lower parts white, with a yellowish tinge; this most perceptible on the tibiæ. Each feather with a medial longitudinal ovate spot of blackish-brown; more reddish on the lower parts. The chin, throat, and a broad superciliary stripe, are immaculate white. Lower tail-coverts each with a medial acuminate spot of rusty, the shaft black. Upper parts brownish-black; wing-coverts, scapulars, and interscapulars, feathers of the rump, and the upper tail-coverts, narrowly bordered with ochraceous-white, and with concealed quadrate spots of the same; primary coverts, secondaries, and primaries sharply bordered terminally with pure white. Tail black (faintly whitish at the tip), with three (exposed) obscure bands of a more slaty tint; this changing to white on the inner webs, in the form of angular spots forming the bands. Lining of the wing pale ochraceous, transversely spotted with rusty rufous; under primary-coverts with transverse spots of white. Wing, 11.90; tail, 6.40.

Hab. Central Mexico and Southern United States; common as far north as Georgia (accidental in Pennsylvania, Vincent Barnard), on the Atlantic coast, and Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin, in the Mississippi Valley. Exceedingly abundant summer bird on the prairies of Southern Illinois.

Localities: Coban (Salvin, Ibis, III, 1861, 355); E. and N. Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 327); Chester Co., Pa. (breeds; Barnard.)

LIST OF SPECIMENS EXAMINEDNational Museum, 6; Philadelphia Academy, 4; New York Museum, 1; Cambridge Museum, 1; Cab. G. N. Lawrence, 1; R. Ridgway, 3. Total, 16.

Habits. This Hawk appears to be confined to the extreme southern and southwestern portion of the Gulf States. It is not known to occur farther north than South Carolina on the Atlantic, though on the Mississippi it has been traced much farther north. It is most abundant about the Mississippi. It was first discovered by Wilson near Natchez, where he found it quite abundant. Mr. Say afterwards observed it far up the Mississippi, at one of Major Long’s cantonments. On Captain Sitgreave’s expedition to the Zuñi and Colorado Rivers, it was found to be exceedingly abundant in Eastern Texas, as well as in the Indian Territory, more particularly on the Arkansas River and its tributaries.

Dresser states that he found this Hawk by no means an unfrequent bird in Texas, and generally in the same localities with the Nauclerus forficatus. It was not very common near San Antonio, but was occasionally found, and even breeds there, as he procured both the old and the young birds during the summer. In travelling eastward in the month of May, he first noticed them near the Rio Colorado, and was told by the negroes on one of the plantations that they were then nesting. On the 20th of May he shot a female on the banks of that river, from which he extracted a fully formed egg. It was almost round, and rather large for the size of the bird. Eastward from the Colorado he also saw this Hawk quite often.

Ictinia mississippiensis.

Though the species, no doubt, occurs in Mexico, Mr. Sclater states that all the Mexican Ictiniæ which he has seen, collected by Sallè, Boucard, and others, have belonged to I. plumbea (Ibis, 1860, p. 104). A single specimen from Coban, Central America, was obtained by Mr. Salvin, but I. plumbea was by far the most common species of Ictinia in Vera Paz.

This species was first discovered within the territory of the United States by Wilson, in his visit to Natchez. He had noticed the bird sailing about in easy circles, and at a considerable height in the air, generally in company with the Turkey Buzzards, whose manner of flight it almost exactly imitated, so much so as to make it appear either a miniature of that species, or like one of them at a great distance, both being observed to soar at great heights previous to a storm. Wilson conjectures that this apparent similarity of manner of flight may be attributable to their pursuit of their respective kinds of food,—the Buzzard on the lookout for carrion, and the birds of the present species in search of those large beetles that are known to fly in the higher regions of the air, and which, in the three individuals dissected by him, were the only substances found in their stomachs. For several miles, as he passed near Bayou Manahak, the trees were swarming with a kind of Cicada, or locust, that made a deafening noise. He there observed a number of these birds sweeping about among the trees in the manner of Swallows, evidently in pursuit of the insects, which proved indeed, on dissection, to be their principal food.

One of these Hawks was slightly wounded by Wilson, and though disabled and precipitated from a great height exhibited evidence of great strength and an almost unconquerable spirit. As he approached to pick it up, the bird instantly gave battle, striking rapidly with its claws, wheeling round and round, and defending itself with great vigilance and dexterity, while its dark red eye sparkled with rage. His captor wished to preserve it alive, but, notwithstanding all his precautions in seizing it, the Hawk struck one of its claws into his hand with great force, and this could only be disengaged by Wilson’s dividing the sinew of the heel with a pen-knife. As long as the bird afterwards lived with Wilson, it seemed to watch every movement, erecting the feathers of the back of its head, and eying him with a savage fierceness. Wilson was much struck with its great strength, its extent of wing, its energy of character, and its ease and rapidity of flight.

Audubon regards this species as remarkable for its devotion to its young, and narrates that in one instance he saw the female bird lift up and attempt to carry out of his reach one of her fledglings. She carried it in her claws the distance of thirty yards or more.

He also describes their flight as graceful, vigorous, and protracted. At times the bird seems to float in the air as if motionless, or sails in broad and regular circles, then, suddenly closing its wings, is seen to slide along to some distance, and then renews its curves. At other times it sweeps in long undulations with the swiftness of an arrow, passing within touching distance of a branch on which it seeks an insect. Sometimes it is said to fly in hurried zigzags, and at others to turn over and over in the manner of a Tumbler Pigeon. Audubon has often observed it make a dash at the Turkey Buzzard, and give it chase, as if in sport, and so annoy this bird as to drive it to a distance. It feeds on the wing with great ease and dexterity. It rarely, if ever, alights on the earth; and, when wounded, its movements on the ground are very awkward. It is never known to attack birds or quadrupeds of any kind, though it will pursue and annoy foxes and Crows, and drive them to seek shelter from its attacks. The Mississippi Kite is said to be by no means a shy bird, and may be easily approached when alight, yet it usually perches so high that it is not always easy to shoot it.

In Southern Illinois, Mr. Ridgway found this Kite to be a very abundant summer bird on the prairies. There it is found from May till near the end of September, and always associated with the Swallowtail (Nauclerus forficatus.) It breeds in the timber which borders the streams intersecting the prairies; but it is not until the hottest weather of July and August that it becomes very abundant, at this time feeding chiefly upon the large insects which swarm among the rank prairie herbage. Its particular food is a very large species of Cicada, though grasshoppers, and occasionally small snakes (as the species of Eutænia, Leptophis æstivus, etc.), also form part of its food. Its prey is captured by sweeping over the object and picking it up in passing over, both the bill and feet being used in grasping it; the food is eaten as the bird sails, in broad circles, overhead. Mr. Ridgway describes the flight of this Kite as powerful and graceful in the extreme, and accompanied by beautiful and unusual evolutions.

According to Mr. Audubon, the nest of this species is always placed in the upper branches of the tallest trees. It resembles a dilapidated Crow’s nest, and is constructed of sticks slightly put together, Spanish moss, strips of pine bark, and dry leaves. The eggs are three in number, nearly globular, and are described by Mr. Audubon as of a light greenish tint, blotched thickly over with deep chocolate-brown and black; but the eggs thus described are those of some totally different species.

The same writer mentions that a pair of these Hawks, whose nest was visited by a negro sailor, manifested the greatest displeasure, and continued flying with remarkable velocity close to the man’s head, screaming, and displaying the utmost rage.

The description given by Mr. Audubon of the egg of this species, and also that in my North American Oölogy, of the drawing of an egg said to be of this bird, taken in Louisiana by Dr. Trudeau, do not correspond with an egg in the cabinet of the Boston Society of Natural History, formerly in that of the late Dr. Henry Bryant. This egg measures 1.50 inches in length by 1.32 in breadth, is very nearly globular, but is also much more rounded at one end, and tapering at the other. It is entirely unspotted and of a uniform chalky whiteness, with an underlying tinge of a bluish green. It was found by Mr. C. S. McCarthy in the Indian Territory, on the north fork of the Canadian River, June 25, 1861. The nest was made of a few sticks, and was in the fork of a horizontal branch, fifteen feet from the ground. There were two eggs in the nest.

It was also found breeding by Mr. J. H. Clark at Trout Creek, Indian Territory, June 21, and by Dr. E. Palmer at the Kiowa Agency (S. I. 13,534).

Genus ROSTRHAMUS, Lesson

Rostrhamus, Less. 1831. (Type, Falco hamatus, Illig.)

Gen. Char. Wings and tail large, the latter emarginated. Bill very narrow, the upper mandible much elongated and bent, the tip forming a strong pendent hook; lower mandible drooping terminally, the gonys straight; the upper edge arched, to correspond with the concavity of the regular commissure. Nostril elongate-oval, horizontal. Tarsus short, about equal to middle toe, with a continuous frontal series of transverse scutellæ; claws extremely long and sharp, but weakly curved; inner edge of the middle claw slightly pectinated. Third to fourth quills longest; outer five with inner webs sinuated.

53081, ♀. ¼

53081, ♀. ½

53081, ♀. ½

Rostrhamus sociabilis.

The species of this genus are two in number, and are peculiar to the tropical portions of America, one of them being confined to the Amazon region, the other extending to Florida in one direction and Buenos Ayres on the other. Their nearest allies are the species Circus and Elanus, like them inhabiting marshy localities, where their food is found, which consists, in large part, of small mollusca.

Species and RacesCommon Characters. Adult. Prevailing color plumbeous-black, or bluish-plumbeous; the tail and primaries black. Entirely concolored, or with white tail-coverts. Cere and feet orange-red. Young. Spotted with blackish-brown and ochraceous, the former prevailing above, the latter beneath.

1. R. sociabilis. Tail-coverts, with terminal and basal zones of the tail, white; that of the tail more or less shaded with grayish-brown. Adult. Uniform blackish-plumbeous, darker on the head, quills, and tail. Hab. South America, West Indies, and Florida.

Plumbeous of a glaucous cast, the head dark plumbeous, and the wing-coverts lighter, inclining to grayish-brown. Wing, 13.25–15.50; tail, 6.75–8.25; bill, .85–1.04; tarsus, 1.70–2.40; middle toe, 1.40–1.55. (2 sp. P. A. N. S.) Hab. Florida and West Indies … var. plumbeus.

Plumbeous of a blackish cast, the head deep black, and the wing-coverts not lighter, and not inclining to brownish. Wing, 12.90–14.00; tail, 7.60–7.80; bill, .90–1.25; tarsus, 1.50–1.80; middle toe, 1.45–1.65. Hab. South America … var. sociabilis.76

2. R. hamatus.77 Tail-coverts, with end and base of the tail, slaty-black. Adult. Uniform bluish-plumbeous, darker on the head, wings, and tail. Tail uniform black, or with two narrow, interrupted, white bands across the middle portion (♂, Brazil, B. S. Coll.). Wing, 11.00–12.00; tail, 5.00–7.00; bill, 1.02–1.07; tarsus, 1.75–1.90; middle toe, 1.45. Hab. Amazon region of South America.

Rostrhamus sociabilis, var. plumbeus, RidgwayHOOK-BILL KITE; EVERGLADE KITERostrhamus sociabilis, Vieill. D’Orb. Hist. Nat. Cuba, av. p. 15.—Cass. Birds N. Am. 1858, 38.—Maynard, Birds Florida, Prospectus, 1872.

Sp. Char. Adult male (No. 61,187, Everglades, Florida; C. J. Maynard). Prevailing color plumbeous, becoming black on the secondaries, primaries, and tail, somewhat brownish-ashy on the wing-coverts, and with a glaucous cast on the neck, the head becoming nearly black anteriorly. Tail-coverts (the longer of the upper and all of the lower) and base of the tail pure white, this occupying more than the basal half of the outer feather, and changing into grayish-brown next the black; tail with a terminal band of grayish-brown, about .75 wide. Inner webs of primaries marbled, anterior to their emargination, with grayish and white. Tibiæ tinged with rusty fulvous. Wing-formula, 4, 3, 5–2–6–7, 1. Wing, 14.01; tail, 7.25; culmen, .95; tarsus, 1.90; middle toe, 1.55; hind claw, 1.10, the toe, .90. Bill deep black; cere and naked lore bright orange-red; feet deep orange-red.