полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 3

After having paired, the Marsh Hawks invariably keep together, and labor conjointly in the construction of the nest, in sitting upon the eggs, and in feeding the young. Their nests are variously constructed as to materials, usually chiefly of hay somewhat clumsily wrought together into the form of a nest, but never very nicely interwoven; occasionally, in more northern localities, they are lined with feathers, in some cases with pine-needles and small twigs.

Richardson states that all the nests of this Hawk observed by him were built on the ground by the side of small lakes, of moss, grass, feathers, and hair, and contained from three to five eggs, of a bluish-white color, and unspotted. The latter measured 1.75 inches in length, and were an inch across where widest. The position and manner of constructing the nest correspond with my own experience, but the size of the eggs does not. The nests have been invariably on the ground, near water, built of dry grass, and lined with softer materials.

Mr. Audubon gives a very minute account of a nest which he found on Galveston Island, Texas. It was about a hundred yards from a pond, on a ridge just raised above the marsh, and was made of dry grass; the internal diameter was eight, and the external twelve inches, with the depth of two and a half. No feathers were found. This absence of a warm lining in Texas really proves nothing. A warm lining may be required in latitude 65° north, and the same necessity not found in one of 29°. A nest observed in Concord, Mass., by Dr. H. R Storer, was on the edge of a pond, and was warmly lined with feathers and fine grasses. Many other instances might be named.

The eggs found in the Galveston nest were four in number, smooth, considerably rounded or broadly elliptical, bluish-white, 1.75 inches in length, and 1.25 in breadth. Another nest, found under a low bush on the Alleghanies, was constructed in a similar manner, but was more bulky; the bed being four inches above the earth, and the egg slightly sprinkled with small marks of pale reddish-brown.

The prevalent impression that the eggs of this Hawk are generally unspotted, so far as I am aware, is not correct. All that I have ever seen, except the eggs above referred to from Texas, and a few others, have been more or less marked with light-brown blotches. These markings are not always very distinct, but, as far as my present experience goes, they are to be found, if carefully sought. In 1856 I received from Dr. Dixon, of Damariscotta, a nest with six eggs of a Hawk of this species. The female had been shot as she flew from the nest. With a single exception, all the eggs were very distinctly blotched and spotted. In shape they were of a rather oblong-oval, rounded at both ends, the smaller end well defined. They varied in length from 2.00 to 1.87 inches, and in breadth from 1.44 to 1.38 inches. Their ground-color was a dirty bluish-white, which in one was nearly unspotted, the markings so faint as to be hardly perceptible, and only upon a close inspection. In all the others, spots and blotches of a light shade of purplish-brown occured, in a greater or less degree, over their entire surface. In two, the blotches were large and well marked; in the others, less strongly traced, but quite distinct.

The nest was found in a tract of low land, covered with clumps of sedge, on one of which it had been constructed. It is described as about the size of a peck basket, circular, and composed entirely of small dry sticks, “finished off or topped out with small bunches of pine boughs.” There was very little depth to the nest, or not enough to cover the eggs from view in taking a sight across it. “No feathers were found in or about it. It was simply made of small dry sticks, about six inches thick, with about one inch of pine boughs for finishing off the nest.” The eggs were found about the 20th of May. They contained young at least two weeks advanced, showing that the bird began to lay in the latter part of April, and to sit upon her eggs early in the following month.

It will be thus seen that the eggs of this Hawk vary greatly in size and shape, and in the presence or absence of marking, varying in length from 1.75 to 2.00 inches, and in breadth from 1.25 to 1.50, and in shape from an almost globular egg to an elongated oval. Some are wholly spotless, and others are very strongly and generally blotched with well-defined purplish-brown.

This Hawk was found breeding in the Humboldt Valley by Mr. C. S. M‘Carthy, on the Yellowstone by Mr. Hayden, at Fort Benton by Lieutenant Mullan, at Fort Resolution by Mr. Kennicott, at Fort Rae and at Fort Simpson by Mr. Ross, at La Pierre House by Lockhart, and on the Lower Anderson by Mr. MacFarlane.

Genus NISUS, Cuvier

Accipiter, Briss. 1760. (Type, Falco nisus, Linn.)

Nisus, Cuv. 1799. (Same type.)

Astur, Lacép. 1801. (Type, Falco palumbarius, Linn.)

Dædalion, Savig. 1809. (Same type.)

Dædalium, Agass. (Same type.)

Sparvius, Vieill. 1816. (Same type.)

Jerax, Leach, 1816. (Same type.)

Aster, Swains. 1837. (Same type.)

Micronisus, Gray, 1840. (Type, Falco gabar, Daud.)

Phabotypus, Glog. 1842. (Same type.)

Hieraspiza, 1844, Jeraspiza, 1851, and Teraspiza, 1867, Kaup. (Type, Falco tinus, Latham.)

Hieracospiza, Agas. (Same type.)

Nisastur, Blas. 1844. (Same type.)

Urospiza, 1845, Urospizia, 1848, and Uraspiza, 1867, Kaup. (Type, Sparvius cirrhocephalus, Vieill.)

Leucospiza, Kaup, 1851. (Type, Falco novæ-hollandiæ, Gmel.)

Cooperastur, Bonap. 1854. (Type, Accipiter cooperi, Bonap.)

Erythrospiza, Kaup, 1867. (Type, A. trinotatus Temm.? not of Bonap. 1830!)

Gen. Char. Form slender, the tail long, the wings short and rounded, the feet slender, the head small, and bill rather weak. Bill nearly as high through the base as the length of the chord of the culmen, its upper outline greatly ascending basally; commissure with a prominent festoon. Superciliary shield very prominent. Nostril broadly ovate, obliquely horizontal. Tarsus longer than the middle toe, the frontal and posterior series of regular transverse scutellæ very distinct, and continuous, sometimes fused into a continuous plate (as in the Turdinæ!). Outer toe longer than the inner; claws strongly curved, very acute. Wing short, much rounded, very concave beneath; third to fifth quills longest; first usually shortest, never longer than the sixth; outer three to five with inner webs cut (usually sinuated). Tail long, nearly equal to wing, usually rounded, sometimes even, more rarely graduated (Astur macrourus) or emarginated (some species of subgenus Nisus).

SubgeneraLess than one third of the upper portion of the tarsus feathered in front, the feathering widely separated behind; frontal transverse scutellæ of the tarsus and toes uninterrupted in the neighborhood of the digito-tarsal joint, but continuous from knees to claws. Tarsal scutellæ sometimes fused into a continuous plate … Nisus.

More than one third (about one half) of the upper portion of the tarsus feathered in front, the feathering scarcely separated behind; frontal transverse scutellæ of the tarsus and toes interrupted in the region of the digito-tarsal joint, where replaced by irregular small scales. Tarsal scutellæ never fused … Astur.

The species of this genus are exceedingly numerous, about fifty-seven being the number of nominal “species” recognized at the present date. Among so many species, there is, of course, a great range of variation in the details of form, so that many generic and subgeneric names have been proposed and adopted to cover the several groups of species which agree in certain peculiarities of external structure. That too many genera and subgenera have been recognized is my final conclusion, after critically examining and comparing forty of the fifty-seven species of Gray’s catalogue (Hand List of Birds, I, 1869, pp. 29–35). The variation of almost every character ranges between great extremes; but when all the species are compared, it is found that, taking each character separately, they do not all correspond, and cross and re-cross each other in the series in such a manner that it is almost impossible to arrange the species into well-defined groups. From this genus I exclude Lophospiza, Kaup (type, L. trivirgatus); Asturina, Vieill. (type, A. nitida); Rupornis, Kaup (type, R. magnirostris); Buteola, Dubus (= Buteo, type, B. brachyura, Vieill.); included by Gray under Astur, as subgenera, and Tachyspiza, Kaup (type, T. soloensis); and Scelospiza, Kaup (type, S. francesii); which are given by Gray as subgenera of Micronisus, Gray (type, Accipiter gabar), the species of the typical subgenus of which, as arranged in Gray’s Hand List, I refer to Nisus. All these excluded names I consider as representing distinct genera.

The species of this genus are noted for their very predatory disposition, exceeding the Falcons in their daring, and in the quickness of their assault upon their prey, which consists chiefly of small birds.

Subgenus NISUS, CuvierAccipiter, Brisson, 1760.81

Nisus, Cuvier, 1799. (Type, Falco nisus, Linn.; A. fringillarius (Ray), Kaup.)

Jerax, Leach, 1816. (Same type.)

Cooperastur, Bonap. 1854. (Type, Accipiter cooperi, Bonap.)

Hieraspiza, 1844, Jeraspiza, 1851, and Teraspiza, 1867, Kaup. (Type, Falco tinus, Lath.)

Hieracospiza, Agass. (Same type.)

Urospiza, 1845, Urospizia, 1848, and Uraspiza, 1867, Kaup. (Type, Sparvius cirrhocephalus, Vieill.)

Erythrospiza, Kaup, 1867. (Type, A. trinotatus (Temm.?))

Micronisus, Gray, 1840. (Type, Falco gabar, Daud.)

Nisastur, Blas. 1844. (Same type.)

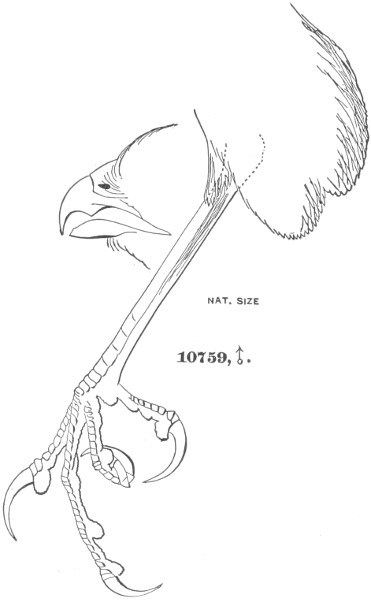

10759, ♂. nat. size

Nisus fuscus.

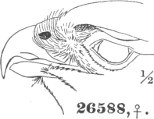

26588, ♀. ½

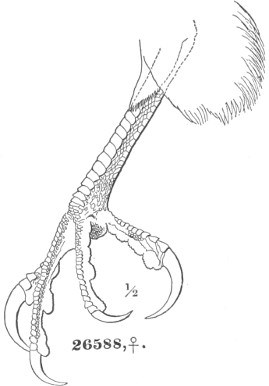

26588, ♀. ½

Nisus cooperi.

The species of this subgenus are generally of small size and slender form; but with a graceful and apparently delicate structure they combine remarkable strength and unsurpassed daring. They differ from the species of Astur mainly in less robust organization. The species are very numerous, and most plentiful within the tropical regions. The Old World possesses about thirty, and America about fifteen, nominal species. Several South American species are intimately related to the two North American ones, and may prove to be only climatic races of the same species; thus, erythrocnemis, Gray (Hand List, p. 32, No. 305) may be the intertropical form of fuscus, and chilensis, Ph. and Landb. (Hand List, No. 314), that of cooperi. But the material at my command is too meagre to decide this.

26588, ♀. ¼

Nisus cooperi.

26588, ♀. ¼

Nisus cooperi.

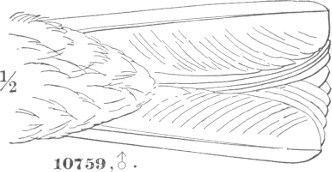

10759, ♂. ½

Nisus fuscus.

In consequence of the insufficient material for working up the South American species, I shall omit them all from the following synopsis of the North American species and races.82

Species and RacesCommon Characters. Adult. Above bluish slate-color; the tail with obscure bands of darker, and narrowly tipped with white. Beneath transversely barred with white and pinkish-rufous; the anal region and crissum immaculate white. Young. Above grayish umber-brown, the feathers bordered more or less distinctly with rusty; scapulars with large white spots, mostly concealed; tail-bands more distinct than in the adult. Beneath white, longitudinally striped with dusky-brown.

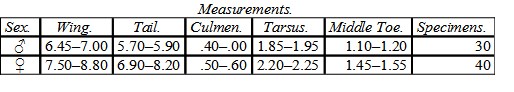

1. N. fuscus. Middle toe shorter than the bare portion of the tarsus, in front; tarsal scutellæ fused into a continuous plate in the adult male. Tail nearly even. Top of head concolor with the back; tail merely fading into whitish at the tip. Concealed white spots of the scapulars very large and conspicuous. Wing, 6.45–8.80; tail, 5.70–8.20; culmen, .40–.60; tarsus, 1.85–2.25; middle toe, 1.10–1.55. Hab. Whole of North America and Mexico.

2. N. cooperi. Middle toe longer than the bare portion of the tarsus, in front; tarsal scutellæ never fused. Tail much rounded. Top of the head much darker than the back; tail distinctly tipped with white; concealed white spots of the scapulars very small, or obsolete. Wing, 8.50–11.00; tail, 7.50–10.50; culmen, .60–.80; tarsus, 2.10–2.75; middle toe, 1.30–1.85. Hab. Whole of North America and Mexico.

Adult. Rufous markings beneath, in form of detached bars, not exceeding the white ones in width; dark slate of the pileum and nape abruptly contrasted with the bluish-plumbeous of the back; upper tail-coverts narrowly tipped with white; scapulars with concealed spots of white. Young. White beneath pure; tibiæ with narrow longitudinal spots of brown. Wing, 9.00–11.00; tail, 8.00–9.80; culmen, .65–.80; tarsus, 2.45–2.75; middle toe, 1.55–1.85. Hab. Eastern region of North America; Eastern Mexico … var. cooperi.

Adult. Rufous markings beneath, in form of broader bars, connected along the shaft, almost uniform on the breast; black of the pileum and nape fading gradually into the dusky plumbeous of the back; upper tail-coverts not tipped with white, and scapulars without concealed spots of the same. Young. White beneath strongly tinged with ochraceous; tibiæ with broad transverse spots of brown. Wing, 8.50–10.60; tail, 7.50–10.50; culmen, .60–.75; tarsus, 2.10–2.75; middle toe, 1.30–1.75. Hab. Western region of North America; Western Mexico … var. mexicanus.

Nisus fuscus (Gmel.) KaupSHARP-SHINNED HAWKFalco fuscus, Gmel. Syst. Nat. p. 283, 1789.—Lath. Ind. Orn. p. 43, 1790; Syn. I, 98, 1781; Gen. Hist. I, 283, 1821.—Mill. Cim. Phys. pl. xviii, 1796.—Daud. Tr. Orn. II, 86, 1800.—Shaw, Zoöl. VII, 161, 1809.—Aud. B. Am. pl. ccclxxiii, 1821; Orn. Biog. IV. 522, 1831.—Brew. (Wils.) Am. Orn. 685, 1852.—Peab. B. Mass. III, 78, 1841.—Thomp. Nat. Hist. Verm. p. 61, 1842.—Nutt. Man. 87, 1833. Accipiter fuscus, Bonap. Eur. & N. Am. B. p. 5, 1838; Consp. Av. 32, 1850.—Gray, List B. Brit. Mus. 38, 1844; Gen. B. fol. sp. 4, 1844.—Cass. B. Cal. & Tex. 95, 1854; Proc. Ac. Nat. Sc. Phil. 1855, 279; Birds N. Am. 1858, 18.—Strickl. Orn. Syn. I, 108, 1855.—Woodh. Sitgr. Exp. Zuñi & Colorad. p. 61, 1853.—Cooper & Suckley, P. R. R. Rep’t, VII, ii, 146, 1860.—Heerm. Williamson’s Rep. 33.—Newb. Williamson’s Rep. 74.—Coues, Pr. Ac. Nat. Sc. Phil. Jan. 1866, p. 7.—Blakist. Ibis, III, 1861, 317 (fresh eggs).—Gray, Hand List, I, 32, 1869. Astur fuscus, De Kay, N. Y. Zoöl. II, 17, pl. ii, fig. 2 (juv. ♂), 1844.—Giraud, B. Long Isl’d, p. 19, 1844. Nisus fuscus, Kaup, Monog. Falc. Cont. Orn. 1850, p. 64. Falco dubius, Gmel. Syst. Nat. 1789, p. 281.—Lath. Ind. Orn. p. 43, 1790; Syn. Supp. I, 37, 1802; Gen. Hist. I, 279, 1821.—Daud. Tr. Orn. 1800, II, 122. Falco velox, Wils. Am. Orn. pl. xlv, f. 1, 1808.—Bonap. An. Lyc. N. Y. II, 29, 1433; Isis, 1832, p. 1137. Accipiter velox, Beech. Voy. Zoöl. p. 15. Astur velox, James. (Wils.) Am. Orn. I, 68, 1831. Falco pennsylvanicus, Wils. Am. Orn. pl. xlvi, fig. 1, 1808.—Lath. Gen. Hist. I, 280, 1820.—Temm. Pl. Col. 67. Accipiter pennsylvanicus, Vig. Zoöl. Journ. I, 338.—Steph. Zoöl. XIII, ii, 32, 1815.—Rich. Faun. Bor.-Am. II, 44, 1831.—Jard. (Wils.) Am. Orn. II, pp. 210, 215, 1832.—Swains. Classif. B. II, 215, 1837. Astur pennsylvanicus, Less. Man. Orn. I, 92.—James. (Wils.) Am. Orn. I, 70, 1831. Nisus pennsylvanicus, Cuv. Règ. An. (ed. 2), I, 334, 1829.—Less. Tr. Orn. p. 59, 1831. Falco columbarius, var., Shaw. Zoöl. VII, 189, 1809. Accipiter ardosiacus, Vieill. Enc. Méth. III, 1274, 1823. Accipiter fringilloides (not of Vigors!), Jard. (Wils.) Am. Orn. II, 215, 1832. ? Nisus pacificus, Lesson, Man. et d’Oiseaux, 1847, 177 (Acapulco to California. Square tail). Accipiter fuscus, Brewer, Oölogy, 1857, 18, pl. III, f. 23, 29; pl. V, f. 54.

Sp. Char. Adult male (11,990, District of Columbia; A. J. Falls). Above deep plumbeous, this covering head above, nape, back, scapulars, wings, rump, and upper tail-coverts; uniform throughout, scarcely perceptibly darker anteriorly. Primaries and tail somewhat lighter and more brownish; the latter crossed by four sharply defined bands of brownish-black, the last of which is subterminal, and broader than the rest, the first concealed by the upper coverts; tip passing very narrowly (or scarcely perceptibly) into whitish terminally. Occipital feathers snowy-white beneath the surface; entirely concealed, however. Scapulars, also, with concealed very large roundish spots of pure white. Under side of primaries pale slate, becoming white toward bases, crossed by quadrate spots of blackish, of which there are seven (besides the terminal dark space) on the longest. Lores, cheeks, ear-coverts, chin, throat, and lower parts in general, pure white; chin, throat, and cheeks with fine, rather sparse, blackish shaft-streaks; ear-coverts with a pale rufous wash. Jugulum, breast, abdomen, sides, flanks, and tibiæ with numerous transverse broad bars of delicate vinaceous-rufous, the bars medially somewhat transversely cordate, and rather narrower than the white bars; laterally, the pinkish-rufous prevails, the bars being connected broadly along the shafts; tibiæ with rufous bars much exceeding the white ones in width; the whole maculate region with the shaft of each feather finely blackish. Anal region scarcely varied; lower tail-coverts immaculate, pure white. Lining of the wing white, with rather sparse cordate, or cuneate, small blackish spots; axillars barred about equally with pinkish-rufous and white. Wing, 6.60; tail, 5.70; tarsus, 1.78; middle toe, 1.20. Fifth quill longest; fourth but little shorter; third equal to sixth; second slightly shorter than seventh. Tail perfectly square.

Adult female (19,116, Powder River; Captain W. F. Raynolds, U. S. A.). Scarcely different from the male. Above rather paler slaty; the darker shaft-streaks rather more distinct than in the male, although they are not conspicuous. Beneath with the rufous bars rather broader, the dark shaft-streaks less distinct; tibiæ about equally barred with pinkish-rufous and white. Wing, 7.70; tail, 6.90; tarsus, 2.10; middle toe, 1.40. Fourth and fifth quills equal and longest; third equal to sixth; second equal to seventh; first three inches shorter than longest.

Young male (41,890, Philadelphia; J. Krider.) Above umber-brown; feathers of the head above edged laterally with dull light ferruginous; those of the back, rump, the upper tail-coverts, scapulars, and wing-coverts bordered with the same; scapulars and rump showing large, partially exposed, roundish spots of pure white. Tail as in adult. Sides of the head and neck strongly streaked, a broad lighter supraoral stripe apparent. Beneath white, with a slight ochraceous tinge; cheeks, throat, and jugulum with fine narrow streaks of dusky-brown; breast, sides, and abdomen with broader longitudinal stripes of clear umber (less slaty than the back), each with a darker shaft-line; on the flanks the stripes are more oval; tibiæ more dingy, markings fainter and somewhat transverse; anal region and lower tail-coverts immaculate white.

Young female (12,023, Fort Tejon, California; J. Xantus). Similar in general appearance to the young male. Markings beneath broader, and slightly sagittate in form, becoming more transverse on the flanks; paler and more reddish than in the young male; tibiæ with brownish-rufous prevailing, this in form of broad transverse spots.

Hab. Entire continent of North America, south to Panama; Bahamas (but not West Indies, where replaced by A. fringilloides, Vig.).

Localities: Oaxaca (Scl. 1858, 295); Central America (Scl. Ibis, I, 218); Bahamas (Bryant, Pr. Bost. Soc. VII, 1859); City of Mexico (Scl. 1864, 178); Texas, San Antonio (Dresser, Ibis, 1866, 324); Western Arizona (Coues); Mosquito Coast (Scl. & Salv. 1867, 280); Costa Rica (Lawr. IX, 134).

LIST OF SPECIMENS EXAMINEDNational Museum, 51; Philadelphia Academy, 14; New York Museum, 7; Boston Society, 5; Museum, Cambridge, 9; Cab. G. N. Lawrence, 1; Coll. R. Ridgway, 4; Museum W. S. Brewer, 1. Total, 92.

Specimens from different regions vary but little in size. The largest are 4,198, ♀, San Francisco, Cal., winter, 16,957, ♀, Hudson’s Bay Territory, and 55,016, ♀, Mazatlan, Mexico, in which the wing ranges from 8.40 to 8.50, the tail 7.00. The smallest females are 45,826, Sitka, Alaska, and 11,791, Simiahmoo, W. T., in which the wing measures about 7.80. A female (32,499) from Orizaba, Mexico, one (8,513) from Fort Yuma, Cal., and one (17,210) from San Nicholas, Lower California, have the wing 8.00, which is about the average. The largest males are 54,336, Nulato, Alaska, 58,137, Kodiak, Alaska, 27,067, Yukon, mouth of Porcupine, and 55,017, Mazatlan, Mexico, in which the wing measures 7.00, the tail 5.60. The smallest males are 5,990, Orange, N. J., 8,514, Shoalwater Bay, W. T., 21,338, Siskiyou Co., Cal., 37,428, Orizaba, Mexico, and 5,584, Bridger’s Pass, Utah; in this series the wing measures 6.50–6.70, the tail 5.40–5.60. A specimen from Costa Rica measures: wing 6.70, tail 5.35. Thus the variation in size will be seen to be an individual difference, rather than characteristic of any region. Some immature specimens from the northwest coast of North America (as 45,828, ♂, Sitka, Rus. Am., 5,845, ♂, Fort Steilacoom, W. T., 11,791, Simiahmoo, Puget Sound, and 8,514, Shoalwater Bay, W. T.) are much darker than others, the brown above inclining to blackish-sepia; no other differences, however, are observable. An adult from the Yukon (54,337, ♀) has the rufous bars beneath remarkably faint, although well defined; another (19,384, ♀, Fort Resolution), in immature plumage, has the longitudinal markings beneath so faint that they are scarcely discernible, and the plumage generally has a very worn and faded appearance. A male in fine plumage (10,759, Fort Bridger, Utah) has the delicate reddish-rufous beneath so extended as to prevail, and with scarcely any variegation on the sides and tibiæ; the bars on the tail, also, are quite obsolete.

Habits. This species is one of the most common Hawks of North America, and its geographical range covers the entire continent, from Hudson’s Bay to Mexico. Sir John Richardson mentions its having been met with as far to the north as latitude 51°. Drs. Gambel and Heermann, and others, speak of it as abundant throughout California. Audubon found it very plentiful as far north as the southern shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. It has been obtained in New Mexico by Mr. McCall, in Mexico by Mr. Pease, in Washington Territory by Dr. Cooper and Dr. Suckley, in Alaska by Mr. Dall, at Fort Resolution by Mr. Kennicott, at Fort Simpson by Mr. B. R. Ross, etc. Messrs. Sclater and Salvin give it as a rare visitant of Guatemala. It has been ascertained to breed in Massachusetts, New Jersey, Wisconsin, California, and Pennsylvania, and it probably does so not only in the intervening States and Territories, but also in all, not excepting the most southern, Florida, where its nest was found by Mr. Wurdemann.