полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 3

Young female (Cuba; Dr. Gundlach, Coll. G. N. Lawrence). Prevailing color above brownish-black, with a glaucous cast on the dorsal region; tail deep black, with a faint greenish-bronze reflection, with white and grayish base and tip, as in the adult. Each feather of the upper parts rather broadly tipped with ochraceous-rufous; crown, occiput, and auriculars streaked longitudinally with the same. Prevailing color of the head and lower parts deep ochraceous, on the head forming a broad superciliary stripe from the forehead back to the occiput; throat and cheeks streaked longitudinally with dusky; crissum immaculate; other lower parts, including lining of the wing, thickly covered with large transverse spots of brownish-black. Upper tail-coverts white, with a blackish shaft-line; tail with the basal third white anteriorly and brownish-ashy next the black, and with a terminal band, about 1.00 wide, of brownish-ashy, passing into white at the tip. Under surface of primaries cream-color anterior to the emargination, towards the ends grayish, with transverse spots of dusky. Wing-formula, 4, 3=5–2–6–7, 1. Wing, 13.90; tail, 8.25; tarsus, 1.90; middle toe, 1.55.

An older specimen in young plumage (11,755, Florida) differs as follows: The colors generally are lighter, the ochraceous being more prevalent and lighter in tint; the throat is immaculate, and the markings beneath more longitudinal. The secondaries and primaries are broadly tipped with ochraceous. Wing, 14.00; tail, 7.20; tarsus, 1.95; middle toe, 1.50.

Hab. West Indies and Southern Florida.

LIST OF SPECIMENS EXAMINEDNational Museum, 3; Coll. C. J. Maynard, 7; Philadelphia Academy, 2; Museum Comp. Zoöl., 3; Coll. R. Ridgway, 1. Total, 16.

Habits. The Black Kite is a Central and South American species, well known in that section, but having no other claim to be regarded as a bird of North America than its presence in a restricted portion of Florida, where it is, in the extreme southern section, not very uncommon, and where it is also known to breed. It was first taken in that peninsula by Mr. Edward Harris, and subsequently by Dr. Heermann. It was supposed by Mr. Harris to breed in Florida, from his meeting with young birds; and this supposition has been confirmed by Mr. Maynard, who has since found them nesting, and procured their eggs.

Mr. Salvin met with what he presumed to be this species in Central America, ascribing the immense flights of Hawks seen by him in the month of March, in the Pacific Coast region, migrating in a northwesterly direction, to this Kite. The bird was well known to the Spaniards under the name of Asacuani,—a term that has become proverbial for a person who is constantly wandering from place to place. Mr. Leyland obtained a single specimen of the Rostrhamus near the Lake of Peten. In the spring of 1870, Mr. Maynard met with several individuals of this species among the Florida everglades. He first observed one on February 18, but was not able to secure it. Visiting the same spot ten days later, with Mr. Henshaw, three birds of this species were shot, and the nest of one was discovered. It was at that time only partly completed, was small, flat, and composed of sticks somewhat carelessly arranged. It was built upon the top of some tall saw-grass, by which it was supported. This grass was so luxuriant and thick that it bore Mr. Maynard up as he sought to reach the nest, which did not contain any eggs. On the 24th of March, Mr. Maynard discovered another nest of this species. It was built in a bush of the Magnolia glauca, and was about four feet from the water. It contained one egg. It was about one foot in diameter, was quite flat, and was composed of sticks carelessly arranged, and lined with a few dry heads of the saw-grass. The female was shot, and found to contain an egg nearly ready for exclusion, but as yet unspotted. Other eggs were subsequently procured through the aid of Seminole Indians, by whom this Hawk is called So-for-funi-kar.

Rostrhamus sociabilis (young).

The usual number of eggs laid by this Kite is supposed to be two, as in three instances no more were found, and this was said to be their complement by the Indians. It also appeared to be somewhat irregular in the time of depositing its eggs.

This Hawk is described as very sociable in its habits, unlike, in this respect, most other birds of prey. Six or eight specimens were frequently seen flying together, at one time, over the marshes, or sitting in company on the same bush. In their flight they resemble the common Marsh Hawk, are very unsuspicious, and may be quite readily approached. The dissection of the specimens showed that this bird feeds largely on a species of freshwater shell (Pomus depressa of Say).

The egg of this species taken in Florida by Mr. Maynard is of a rounded oval shape, equally obtuse at either end, and measures 1.70 inches in length by 1.45 in breadth. The ground-color is a dingy white, irregularly, and in some parts profusely, blotched with groups of markings of a yellowish brown, shading from a light olive-brown to a much duller color, almost to a black hue. These markings in the specimen seen are not grouped around either end, but form a confluent belt around the central portions of the egg. The following description is given by Mr. Maynard of the other specimens taken by him.

Egg No. 1. Ground-color bluish-white, spotted and blotched everywhere with brown and umber. Dimensions, 1.72 × 1.45. No. 2. Ground-color same as No. 1. Two large irregular blotches of dark brown and umber on the larger end, with smaller confluent blotches and streaks of the same, covering nearly the entire surface of that end; smaller end much more sparsely spotted with the same. Dimensions, 1.76 × 1.40. No. 3. Ground-color dirty brown. The entire egg, except the small end, covered with a washing of dark brown, which forms dark irregular blotches at various points, as if the egg had been painted and then taken in the fingers before drying. Dimensions, 1.55 × 1.55.

Genus CIRCUS, Lacepede

Circus, Lacép. 1800, 1801. (Type, Falco æruginosus, Linn.)

Pygargus, Koch, 1816. (Same type.)

Strigiceps, Bonap. 1831. (Type, Falco cyaneus, Linn.)

Glaucopteryx, Kaup, 1844. (Type, Falco cineraceus, Mont.)

Spilocircus, Kaup, 1847. (Type, Circus jardini, Gould.)

Pterocircus, Kaup, 1851. (Same type.)

Spizacircus and Spiziacircus, Kaup, 1844 and 1851. (Type, Circus macropterus, Vieill.)

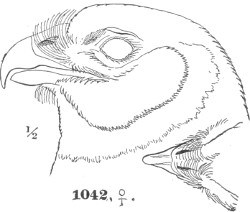

1042, ♀. ½

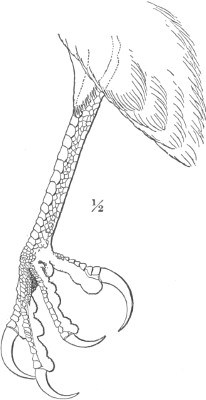

½

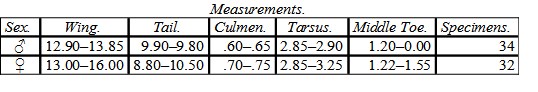

¼

Circus hudsonius.

Gen. Char. Form very slender, the wings and tail very long, the head small, bill weak, and feet slender. Face surrounded by a ruff of stiff, compact feathers, as in the Owls (nearly obsolete in some species). Bill weak, much compressed; the upper outline of the cere greatly ascending basally, and arched posteriorly, the commissure with a faint lobe; nostril oval, horizontal. Loral bristles fine and elongated, curving upwards, their ends reaching above the top of the cere. Superciliary shield small, but prominent. Tarsus more than twice the middle toe, slender, and with perfect frontal and posterior continuous series of regular transverse scutellæ; toes slender, the outer longer than the inner; claws strongly curved, very acute. Wings very long, the third or fourth quills longest; first shorter than the sixth; outer three to five with inner webs sinuated. Tail very long, about two thirds the wing; rounded.

The relationships of this well-marked genus are, to Accipiter on the one hand, and Elanus on the other; nearest the former, though it is not very intimately allied to either. I cannot admit the subgenera proposed by various authors (see synonomy above), as I consider the characters upon which they are based to be merely of specific importance, scarcely two species being exactly alike in the minute details of their form.

The species are quite numerous, numbering about twenty, of which only about four (including the climatic sub-species, or geographical races) are American. North America possesses but one (C. hudsonius, Linn.), and this, with the C. cinereus, Vieill., of South America, I consider to be a geographical race of C. cyaneus of Europe.

The birds of this genus frequent open, generally marshy, localities, where they course over the meadows, moors, or marshes, with a steady, gliding flight, seldom flapping, in pursuit of their food, which consists mainly of mice, small birds, and reptiles. Their assault upon the latter is sudden and determined, like the “Swift Hawks,” or the species of Accipiter.

In the following synopsis, I include only the three forms of C. cyaneus, giving the characters of the European race along with those of the two American ones.

Species and RacesC. cyaneus. Wing, 12.50–16.00; tail, 9.00–10.70; culmen, .60–.80; tarsus, 2.42–3.25; middle toe, 1.10–1.55. Third to fourth quills longest; first shorter than sixth or seventh; outer four with inner webs sinuated. Adult male.78 Above pearly-ash, with a bluish cast in some parts; breast similar; beneath white, with or without rufous markings. Adult female. Above brown, variegated with ochraceous on the scapulars and wing-coverts; beneath yellowish-white or pale ochraceous, with a few longitudinal stripes of brown. Young (of both sexes). Like the adult female, but darker brown above, the spotting deeper ochraceous, or rufous; beneath pale rufous, the stripes less distinct.

Tail and secondaries without a subterminal band of dusky; lower parts without any markings.

Wing, 12.50–15.00; tail, 9.00–10.70; culmen, .60–.75; tarsus, 2.70–2.85; middle toe, 1.10–1.35. Hab. Europe … var. cyaneus.79

Tail and secondaries with a subterminal band of dusky; lower parts with rufous markings.

Wing, 12.90–16.00; tail, 9.00–10.50; culmen, .65–.75; tarsus, 2.90–3.25; middle toe, 1.20–1.55. Lower parts with scattered irregular specks, or small cordate spots, of reddish-rufous. Hab. North and Middle America … var. hudsonius.

Wing, 12.40–14.50; tail, 8.50–10.50; culmen, .62–.81; tarsus, 2.42–3.00; middle toe, 1.20–1.50. Lower parts with numerous regular transverse bars of reddish-rufous Hab. South America … var. cinereus.80

Circus cyaneus, var. hudsonius (Linn.)MARSH HAWK; AMERICAN HARRIERFalco hudsonius, Linn. Syst. Nat. p. 128, 1766.—Gmel. Syst. Nat. p. 277, 1789.—Lath. Syn. I, 91, sp. 76, 1781; Gen. Hist. I, p. 97, sp. C. 1821.—Daud. Tr. Orn. II, 173, 1800.—Shaw, Zoöl. VII, 165, 1809. Circus hudsonius, Vieill. Ois. Am. Sept. pl. ix, 1807.—Cass. B. Cal. & Tex. p. 108, 1854; Birds N. Am. 1858, p. 38.—Heerm. P. R. R. Rep’t, II, 33, 1855.—Kennerly, P. R. R. Rep’t, III, 19, 1856.—Newb. P. R. R. Rep’t, VI, 74, 1857.—Coop. & Suck. P. R. R. Rep’t, XII, ii, 150, 1860.—Strickl. Orn. Syn. I, 150, 1855.—Coues, Prod. B. Ariz. 13, 1866.—Blakist. Ibis, 1861, 319.—Lord, Pr. R. A. I. IV, 1864, 110 (Brit. Coll.). Circus cyaneus hudsonius, Schleg. Mus. Pays-Bas, Circi, 2, 1862. Circus cyaneus, var. hudsonius, (Ridgway) Coues, Key, 1872, 210.—Gray, Hand List, I, 37, 1869. Strigiceps hudsonius, Bonap. Consp. Av. p. 35, 1850. Falco spadicens, Gmel. Syst. Nat. p. 273, 1789.—Forst. Phil. Trans. LXII, 383, 1772. Falco buffoni, Gmel. Syst. Nat. p. 277, 1789.—Lath. Gen. Hist. I, 98, D, 1821. Falco uliginosus, Gmel. Syst. Nat. p. 278, 1789.—Lath. Ind. Orn. p. 40, 179; Syn. I, 90, 1781; Gen. Hist. I, 271, 1821.—Daud. Tr. Orn. II, 173, 1800.—Wils. Am. Orn. pl. li, f. 2, 1808.—Sab. App. Frankl. Exp. p. 671. Circus uliginosus, Vieill. Ois. Am. Sept. I, 37, 1807.—De Kay, Zoöl. N. Y. II, 20, pl. iii, figs. 5, 6, 1844.—James. (Wils.) Am. Orn. I, 88, 1831.—Max. Cab. Journ. VI, 1858, 20. Strigiceps uliginosus, Bonap. Eur. & N. Am. B. p. 5, 1838.—Kaup, Monog. Falc. Cont. Orn. 1850, p. 58. Falco cyaneus & β. Lath. Ind. Orn. p. 40, 1790; Syn. I, 91, 7 sp. 6 A.—Shaw, Zoöl. VII, 164, 1809. Falco cyaneus, Aud. B. Am. pl. ccclvi, 1831.—James. (Wils.) Am. Orn. IV, 21, 1831.—Bonap. Am. Orn. pl. 12; Ann. Lyc. N. Y. II, 33; Isis, 1832, p. 1538.—Peab. B. Mass. p. 82, 1841. Circus cyaneus, Bonap. Ann. Lyc. N. Y. p. 33.—Jard. (Wils.) Am. Orn. II, 391.—Rich.

Measurements.—♂. Wing, 12.50–13.25; tail, 9.00–9.30; culmen, .60–.70; tarsus, 2.75–2.90; middle toe, 1.10–1.25. Specimens, 8. ♀. Wing, 13.50–15.00; tail, 9.50–10.70; culmen, .75; tarsus, 2.70–2.85; middle toe, 1.25–1.35. Specimens, 4.

Observations.—The adult female of cyaneus is distinguishable from that of hudsonius by lighter colors and less distinct ochraceous blotches on the shoulders. & Swains. Faun. Bor. Am. pl. xxix, 1831.—Aud. Synop. p. 19, 1839.—Brew. (Wils.) N. Am. Orn. Syn. 685, 1852.—Peab. U. S. Expl. Exp. p. 63, 1848.—Woodh. in Sitgr. Rep’t, Exp. Zuñi & Colorad. p. 61, 1853.—Nutt. Man. Orn. U. S. & Can. p. 109, 1833.—Giraud. B. Long Isl’d, p. 21, 1844.—Gray, List B. Brit. Mus. p. 78, 1844.

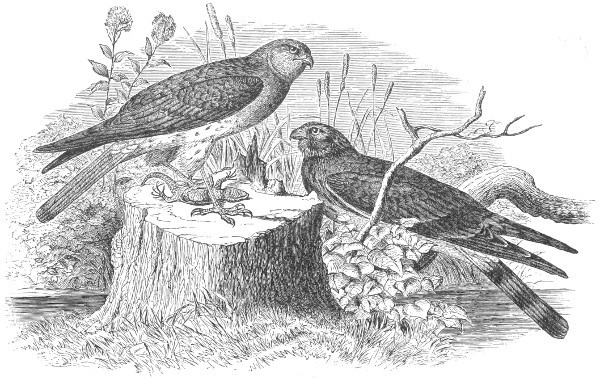

Sp. Char. Adult male (10,764, Washington, D. C., December). Head, neck, breast, and upper parts light cinereous, palest anteriorly where it is uninterruptedly continuous; occiput somewhat darker, with a transverse series of longitudinal dashes of white, somewhat tinged with reddish. Back, scapulars, and terminal third of secondaries, with a dusky wash, the latter fading at tips; five outer primaries nearly black, somewhat hoary on outer webs beyond their emargination; lesser wing-coverts faintly mottled with paler, or with obsolete dusky spots. Upper tail-coverts immaculate pure white. Tail bluish-cinereous, mottled with white toward base; crossed near the end with a distinct band of black, and with about five narrower, very obscurely indicated ones anterior to this; tip beyond the subterminal zone fading terminally into whitish. Whole under side of wing (except terminal third or more of primaries) pure white; immaculate, excepting a few scattered transverse dusky spots on larger coverts. Rest of under parts pure white everywhere, with rather sparse transverse cordate spots of rufous. Wing, 14.00; tail, 9.20; tarsus, 2.80; middle toe, 1.30. Third and fourth quills equal, and longest; second intermediate between fifth and sixth; first 5.81 inches shorter than longest.

Another specimen differs as follows: The fine cinereous above is replaced by a darker and more brownish shade of the same, the head and breast much tinged with rusty. Tail much darker, the last black band twice as broad and near the tip; other bands more numerous (seven instead of five), and although still very obscure on middle feathers are better defined than in the one described; inner webs of tail-feathers (especially the outer ones) tinged with cream-color; white of lower parts tinged with rufous; the deep rufous transverse bars on the breast and sides broader, larger, and more numerous than in No. 16,764; abdomen and tibiæ with numerous smaller cordate spots of rufous; lower tail-coverts with large cordate spots of the same, and a deep stain of paler rufous; lining of wings more variegated. Wing, 14.10; tail, 9.00; tarsus, 2.90; middle toe, 1.30.

Adult female (16,758, Hudson’s Bay Territory; Captain Blakiston). Umber-brown above; feathers of the head and neck edged laterally with pale rufous; lores, and superciliary and suborbital stripes dull yellowish-white, leaving a dusky stripe between them, running back from the posterior angle of the eye. Lesser wing-coverts spattered with pale rufous, this irregularly bordering and indenting the feathers; feathers of the rump bordered with dull ferruginous. Tail deep umber, faintly fading at the tip, and crossed by six or seven very regular, sharply defined, but obscure, bands of blackish; the alternating light bars become paler and more rufous toward the edge of the tail, the lateral feathers being almost wholly pale cream-color or ochraceous, darker terminally; this tint is more or less prevalent on the inner webs of nearly all the feathers. Ear-coverts dull dark rufous, obsoletely streaked with dark brown; the feathers of the facial disk are fine pale cream-color, each with a middle stripe of dark brown; throat and chin immaculate dirty-white, like the supraorbital and suborbital stripes. Beneath dull white, with numerous broad longitudinal stripes of umber-brown; these broadest on the breast, growing gradually smaller posteriorly. Under surface of primaries dull white, crossed at wide intervals with dark-brown irregular bars, of which there are five (besides the terminal dark space) on the longest quill.

Juv. (♀, 15,585, Bridger’s Pass, Rocky Mountains, August; W. S. Wood). Upper parts very dark rich clove-brown, approaching sepia-black; feathers of the head bordered with deep ferruginous, and lesser wing-coverts much spotted with the same, the edges of the feathers being broadly of this color; secondaries and inner primaries fading terminally into whitish; upper tail-coverts tinged with delicate cream-color (immaculate). Tail with four very broad bands of black, the intervening spaces being dark umber on the two middle feathers, on the others fine cinnamon-ochre; the tip also (broadly) of this color. Ear-coverts uniform rich dark snuff-brown, feathers of a satiny texture; feathers of facial disk the same centrally, edged with fine deep rufous. Entire lower parts deep reddish-ochraceous or fulvous-rufous, growing gradually paler posteriorly; immaculate, with the exception of a few faint longitudinal stripes on the breast and sides. Under side of wing as in the last, but much tinged with rufous.

Hab. Entire continent of North America, south to Panama; Cuba, and Bahamas.

Localities: Oaxaca (Scl. 1859, 390); Orizaba (Scl. 1857, 211); Guatemala, winter (Scl. Ibis, I, 221); Cuba (Cab. Journ. II, lxxxiii; Gundlach, Repert. 1865, 222, winter); City of Mexico (Scl. 1864, 178); E. Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 328, resident); W. Arizona (Coues); Bahamas (Bryant, Pr. Bost. Soc. 1867, 65); Costa Rica (Lawr. IX, 134).

LIST OF SPECIMENS EXAMINEDNational Museum, 53; Museum Comp. Zoöl., 24; Boston Society, 8; Philadelphia Academy, 10; Cab. of G. N. Lawrence, 5; R. Ridgway, 6. Total, 106.

Habits. The Marsh Hawk is one of the most widely distributed birds of North America, breeding from the fur regions around Hudson’s Bay to Texas, and from Nova Scotia to Oregon and California. It is abundant everywhere, excepting in the southeastern portion of the United States. Sir John Richardson speaks of it as so common on the plains of the Saskatchewan that seldom less than five or six are in sight at a time (in latitude 55°). Mr. Townsend found it on the plains of the Columbia River and on the prairies bordering on the Missouri. The Vincennes Exploring Expedition obtained specimens in Oregon. Dr. Gambel and Dr. Heermann found it abundant in California. Dr. Suckley’s party obtained specimens in Minnesota; Captain Beckwith’s, in Utah; Captain Pope, Lieutenant Whipple, and Dr. Henry, in New Mexico; and Lieutenant Couch, in Tamaulipas, Mexico. Dr. Woodhouse met with it abundantly from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, throughout the summer, showing conclusively that it breeds in those different sections of country. De la Sagra, Lembeye, and Dr. Gundlach, all give it as a bird of Cuba, but not as breeding there.

Dall records it as very rare on the Yukon, and an occasional summer visitor only at St. Michael’s, where an individual was killed as late as November. Donald Gunn states that it makes its appearance in the fur countries about the opening of the rivers, and departs about the beginning of November. It preys upon small birds and mice, is very slow on the wing, flies very low, and in a manner very different from all other kinds of Hawks.

In Nova Scotia it is very abundant, and is very destructive of young game. Mr. Downes regards it as an indiscriminating feeder upon fish, snakes, and even worms. He took two green snakes from the stomach of one of them.

Circus hudsonius (male and female).

Mr. Dresser found them abundant throughout the whole country east of the Rio Nueces at all seasons of the year. They were more abundant in full blue plumage than elsewhere. Near San Antonio he met with them on the prairies, where they feed on the small green lizards which abound there, and which they are very expert in catching. Dr. Coues mentions them as very abundant in Arizona. Dr. Kennerly met with them on both sides of the Rio Grande wherever there was a marsh of any extent. Flying near the surface, just above the weeds and canes, they round their untiring circles hour after hour, darting after small birds as they rise from cover. Pressed by hunger, they will attack even wild Ducks. Dr. Kennerly also observed them equally abundant in the same localities in New Mexico. Dr. Newberry mentions finding this Hawk abundant beyond all parallel on the plains of Upper Pitt River. He saw several hundred in a single day’s march.

In Washington Territory both Dr. Suckley and Dr. Cooper found this Hawk abundant throughout the open districts, and especially so in winter. Dr. Cooper found it no less common in California, and among several hundreds saw but two birds in the blue plumage. Near Fort Laramie he found it no less common, but there, at least one half were in the blue plumage. From this he infers that the older birds seek the far interior in preference to the seaboard.

Mr. Allen mentions it as common in winter about the savannas in Florida, and Mr. Salvin states that it is a migratory species in Guatemala. It occurred in the Pacific Coast Region, and examples were also received from Vera Paz.

In evidence of the nomadic character of the Marsh Hawk it may be mentioned that specimens asserted to be of this species are in the Leyden Museum that were received from the Philippines and from Kamtschatka.

In Wilson’s time this Hawk was quite numerous in the marshes of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, where it swept over the low grounds, sailing near the earth, in search of a kind of mouse very common in such situations, and was there very generally known as the Mouse Hawk. It is also said to be very serviceable in the Southern rice-fields in interrupting the devastations made by the swarms of Bobolinks. As it sails low and swiftly over the fields, it keeps the flocks in perpetual fluctuation, and greatly interrupts their depredations. Wilson states that one Marsh Hawk was considered by the planters equal to several negroes for alarming the Rice-birds. Audubon, however, controverts this statement, and quotes Dr. Bachman to the effect that no Marsh Hawks are seen in the rice-fields until after the Bobolinks are gone. Dr. Coues, on the other hand, gives this Hawk as resident throughout the year in South Carolina.

According to Audubon, the Marsh Hawk rarely pursues birds on the wing, nor does it often carry its prey to any distance before it alights and devours it. While engaged in feeding, it may be readily approached, surprised, and shot. When wounded, it endeavors to make off by long leaps; and when overtaken, it throws itself on the back and fights furiously. In winter its notes while on the wing are sharp, and are said to resemble the syllables pee-pee-pee. The love-notes are similar to those of the columbarius.

Mr. Audubon has found this Hawk nesting not only in lowlands near the sea-shore, but also in the barrens of Kentucky and on the cleared table-lands of the Alleghanies, and once in the high covered pine-barrens of Florida.