полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 3

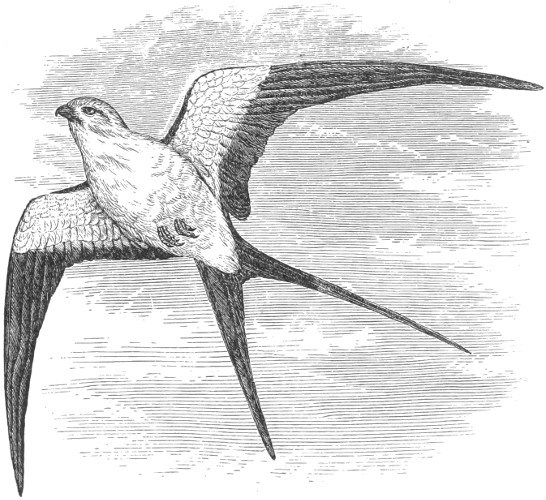

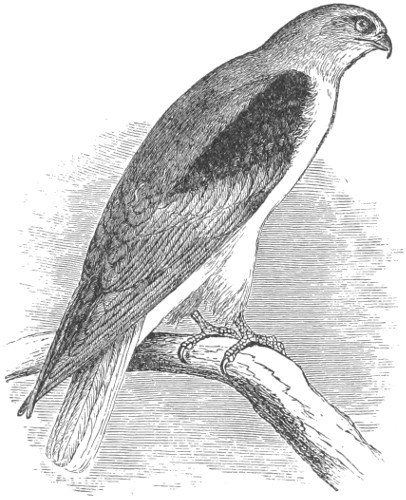

Sp. Char. Adult, male and female. Whole head and neck, lining of wings, broad band across the rump, and entire lower parts, pure white. Interscapulars and lesser wing-coverts, rich, dark, soft, bronzed purplish-black. Rest of upper parts, including lower part of rump, upper tail-coverts, and tail, more metallic slaty-black, feathers somewhat greenish basally, more bluish terminally, with a peculiar, soft milky appearance, and with very smooth compact surface. Tertials almost entirely white, black only at tips. White on under side of wing occupying all the coverts, and the basal half of the secondaries. Wing, 15.40–17.70; tail, 12.50–14.50; tarsus, 1.00–1.30; middle toe, 1.15–1.20.

Younger. Similar, but with the beautiful soft purplish-bronzed black of shoulders and back less conspicuously different from the more metallic tints of other upper parts. Young (youngest? 18,457, Cantonment Burgwyn, New Mexico). The black above less slaty, with a brownish cast, and with a quite decided gloss of bottle-green; secondaries, primary coverts, primaries, and tail-feathers finely margined terminally with white. Feathers of the head and neck with fine shaft-lines of black.

Hab. Whole of South and Middle America, and southern United States; very rarely northward on Atlantic coast to Pennsylvania; along the Mississippi Valley to Minnesota and Wisconsin; breeding in Iowa (Sioux City) and Illinois; exceedingly abundant in August in southern portion of the latter State; Cuba; accidental in England.

Localities: Guatemala (Scl. Ibis. I, 217); Cuba (Cab. Journ. II, lxxxiii); Brazil (Cab. Journ. V, 41); Panama (Lawr. VII, 1861, 289); N. Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 325, common, breeding); Veragua (Salv. 1867, 158); Costa Rica (Lawr. IX, 134); Minnesota (thirty miles north of Mille Lac, lat. 47°; Trippe, Birds of Minn., Pr. Essex Inst. VI, 1871, p. 113).

A pair marked as from England (56,099, ♀, and 56,100, ♂, “in England geschossen”; Schlüter Collection) are smaller than the average of American skins, the female measuring, wing, 15.50; tail, 13.00. The colors of this female, however, are as in American examples. The male has the plumage somewhat different from anything we have seen in the small series of American specimens. The whole upper parts are a polished violaceous slaty-black, this covering the back and lesser wing-coverts, as well as other upper parts. Were a large series of American specimens examined, individuals might perhaps be found corresponding in all respects with the pair in question.

LIST OF SPECIMENS EXAMINEDNational Museum, 9; Philadelphia Academy, 3; New York Museum, 4 (Brazil); Boston Society, 1; Cambridge Museum, 2; Cab. G. N. Lawrence, 3; Coll. R. Ridgway, 1. Total, 23.

Nauclerus forficatus.

Habits. The Swallow-tailed Hawk has an extended distribution in the eastern portion of North America. It is irregularly distributed; in a large part of the country it occurs only occasionally and in small numbers, and is probably nowhere abundant except in the southwestern Gulf States, or along the rivers and inland waters. On the Atlantic coast it has been traced, according to Mr. Lawrence, as far north as New York City. According to Mr. Nuttall, individuals have been seen on the Mississippi as far as St. Anthony’s Falls, in latitude 44°. It is found more or less common along the tributaries of the Ohio and Mississippi, where it is essentially a prairie bird, and breeds in Southern Wisconsin, in Iowa, Nebraska, and Kansas, and throughout Illinois. It has been taken in Cuba, and occasionally also in Jamaica. It is found in Central America, and in South America to Northern Brazil, Buenos Ayres, and, according to Vieillot, to Peru. It nests in South Carolina and in all the States that border on the Gulf of Mexico, frequenting the banks of rivers, but is not found near the seaboard.

Mr. Thure Kumlien noticed a pair of these Hawks in the neighborhood of Fort Atkinson, Wis., in the summer of 1854, and had no doubt they were breeding, though he was not able to find their nest.

Mr. Osbert Salvin, in a letter from San Geronimo, in the Vera Paz (Ibis, 1860, p. 195), states that he has positive information that this Hawk breeds in the mountains about Coban, his chief collector having found a nest there with young the previous year. Specimens had been before that received by Mr. Sclater, forwarded by Mr. Skinner, from the neighborhood of Cajabon, Guatemala. It was said to be more numerous at Belize.

Mr. Dresser informs us that he was so fortunate as to find this graceful bird very abundant in some parts of Texas, and he had a good opportunity of observing and admiring it in its true home. It was occasional about San Antonio de Bexar, where it was usually seen late in July before heavy rains. Near the Rio Grande or in Texas he did not see it at all. At Peach Creek and near Gonzales he found it not unfrequent; and on the Colorado, Brazos, and Trinity Rivers it was one of the most common birds. It only remains there during the summer months, arriving early in April, and breeding later than the other birds of prey. On the 26th of May he found them very abundant on a creek near the Colorado, but none had commenced breeding. They were preparing their nests; and, from the number he saw about one large grove, he judged that they breed in society. On his wounding one of them, the rest came flying over his head in the manner of Seagulls, uttering harsh cries; and he counted forty or fifty over him at one time. He was informed that these Kites build high up in oak, sycamore, or cottonwood trees, sometimes quite far from the creeks.

Mr. Dresser describes this bird as exhibiting a singularly pleasing appearance on the wing, gliding in large circles, without apparent effort, in very rapid flight. The tail is widely spread, and when sailing in circles the wings are almost motionless. One was noticed as it was hunting after grasshoppers. It went over the ground as carefully as a well-trained pointer, every now and then stooping to pick up a grasshopper, the feet and bill seeming to touch the insect simultaneously. They were very fond of wasp grubs, and would carry a nest to a high perch, hold it in one claw, and sit there picking out the grubs. Their stomachs were found to contain beetles and grasshoppers.

Dr. Woodhouse speaks of this Hawk as common in Texas, and also in the country of the Creek and Cherokee nations. He confirms the accounts which have been received of its fondness for the neighborhood of streams, and adds that along the Arkansas and its tributaries it was very abundant.

Mr. Ridgway states that this Hawk arrives in Richland County, Ill., in May, and lives during the summer on the small prairies, feeding there upon small snakes, particularly the little green snake (Leptophis æstivus) and the different species of Eutænia. It builds its nest there among the oak or hickory trees which border the streams intersecting the prairies. Towards the latter part of summer it becomes very abundant on the prairies, being attracted by the abundance of food, which at that season consists very largely of insects, especially Neuroptera. It is most abundant in August, and in bright weather dozens of them may be seen at a time sailing round in pursuit of insects.

Mr. Audubon speaks of the movements of this bird in flight as astonishingly rapid, the deep curves they describe, their sudden doublings and crossings, and the extreme ease with which they seem to cleave the air, never failing to excite admiration. In the States of Louisiana and Mississippi, where, he adds, these birds are very abundant, they arrive in large companies in the beginning of April, and utter a sharp and plaintive note. They all come from the westward; and he has counted upwards of a hundred, in the space of an hour, passing over him in an easterly direction. They feed on the wing, and their principal food is said to be grasshoppers, caterpillars, small snakes, lizards, and frogs. They sweep over the fields, and seem to alight for a moment to secure a snake or some other object. They also frequent the creeks, to pick up water-snakes basking on the floating logs.

On the ground their movements are said to be awkward in the extreme. When wounded, they rarely strike with their talons, or offer serious resistance. They never attack other birds or quadrupeds to prey upon them.

This Hawk is a great wanderer, and a number of instances are on record of its having been taken in Europe. One of these was in Scotland, in 1772; another in England, in 1805.

Mr. R. Owen (Ibis, 1860, p. 241), while travelling from Coban to San Geronimo, in Guatemala, among the mountains, came suddenly upon a large flock of two or three hundred of these Hawks, which were pursuing and preying upon a swarm of bees. At times they passed within four or five yards of him. Every now and then the neck was observed to be bent slowly and gracefully, bringing the head quite under the body. At the same time the foot, with the talons contracted as if grasping some object, would be brought forward to meet the beak. The beak was then seen to open and to close again, and then the head was again raised and the foot thrown back. This movement was repeatedly observed, and it was quite clear to him that the birds were preying upon the bees.

This Hawk constructs its nest on tall trees, usually overhanging or near running water. The nest is like that of the Crow in its general appearance. It is constructed externally of dry twigs and sticks, intermixed with which are great quantities of the long Spanish moss peculiar to the Southern States, and lined with dry grasses, leaves, and feathers. One found by Dr. C. Kollock, of Cheraw, S. C., in May, 1855, containing young, was on a large tree, not near the trunk, but on one of the projecting branches, and difficult of approach.

The eggs are described by Mr. Audubon as from four to six in number, of a greenish-white color, with a few irregular blotches of dark brown at the larger end. The drawing of an egg, obtained by Dr. Trudeau in Louisiana, and which was made by that gentleman, is very nearly spheroidal, and its measurements are, length 1.75 inches, breadth 1.56. It corresponds with Mr. Audubon’s description of the egg of this Hawk.

An egg in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution, taken in Iowa by Mr. Krider, does not correspond very well with the description and figure mentioned. It measures 1.80 in length by 1.40 in breadth; its form is very regularly oval, both ends being of nearly the same shape. The ground-color is a creamy white, one end (the smaller) splashed with large confluent blotches of ferruginous, and the remainder of the surface more sparsely spotted with the same; these rusty blotches are relieved by smaller, sparser spots of very dark brown.

Dr. Cooper, in a letter dated Sioux City, May 21, 1860, mentions finding the nest of this Hawk in a high tree in Northwestern Iowa, latitude 41° 30′. The bird had not begun to lay.

Genus ELANUS, Savigny

Elanus, Sav. 1809. (Type, Falco melanopterus, Daudin.)

Milans, Boie, 1822.

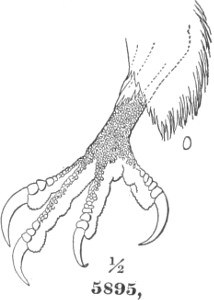

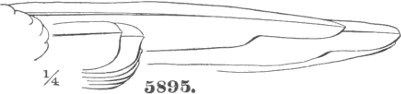

Gen. Char. Bill rather small and narrow, the tip normal; commissure moderately sinuated; upper outline of lower mandible greatly arched, the height at base less than half that through middle; gonys almost straight, declining downward toward tip. Nostril roundish, in middle of cere. Tarsus and toes (except terminal joint) covered with small roundish scales; under surface of claws just perceptibly flattened; sharp lateral ridge on middle claw very prominent; a very slight membrane between outer and middle toes. Second quill longest, third very slightly shorter; first just exceeding fourth; second and third with outer webs slightly sinuated; inner web of first emarginated, of second sinuated. Tail peculiar, emarginated, but the lateral feather much shorter than the middle, the one next to it being the longest.

5895. ½

5895. ½

5895. ¼

Elanus leucurus.

The species of this well-marked genus are confined to the tropical and subtropical portions of the world, and appear to be only two in number, of which one is cosmopolitan, and the other peculiar to the Old World.

Species and RacesCommon Characters. Above pearly ash, becoming white or whitish on the head and tail, with a large black patch covering the lesser-covert region. Lower surface continuous pure white; a black spot on front of, and partly around, the eye.

1. E. leucurus. A large black patch on the lining of the wing, in the region of the primary coverts. First quill very much shorter than the third; second quill longest.

Black patch on lining of the wing restricted to the primary coverts; lesser coverts, on outer surface, not conspicuously bordered anteriorly with white.

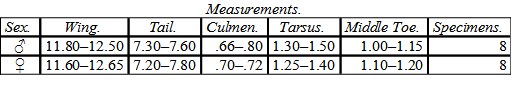

Above deep bluish-ash, with the inner webs of the secondaries appreciably paler, sometimes abruptly white. Wing, 11.60–12.65; tail, 6.80–7.80; culmen, .65–.80; tarsus, 1.20–1.50; middle toe, .94–1.20. Hab. Tropical and subtropical America … var. leucurus.

Above pale ash, with the inner webs of the secondaries hardly, or not at all, appreciably paler than the outer. Wing, 11.00–12.50; tail, 6.20–7.00; culmen, .70–.77; tarsus, 1.10–1.66; middle toe, 1.05–1.08. Hab. Western Australia … var. axillaris.71

Black patch on the lining of the wing extending over the whole of the lesser coverts; lesser coverts, on the outside, conspicuously bordered anteriorly with white.

Similar to var. axillaris, except as above. Wing, 11.75–12.30; tail, 6.30–7.00; culmen, .75–.80; tarsus, 1.10–1.40; middle toe, 1.15–1.25. Hab. Southern Australia … var. scriptus.72

2. E. cæruleus. No black on lining of the wing. First quill usually longer than the third, never very much shorter; second longest. Colors darker than in E. leucurus.

Wing, 12.00; tail, 6.10; culmen, .75; tarsus, 1.25; middle toe, 1.20. No ashy tinge on side of breast. Hab. Southern Europe and North Africa … var. cæruleus.73

Wing, 9.50–10.70; tail, 5.40–5.75; culmen, .65–.70; tarsus, 1.05–1.10; middle toe, 1.00–1.10. Sides of the breast strongly tinged with ashy. Hab. Southern Africa and India … var. minor.74

Elanus leucurus (Vieillot)BLACK-SHOULDERED KITE; WHITE-TAILED KITEMilvus leucurus, Vieill. Nouv. Dict. Hist. Nat. XX, 556, 1816; Enc. Méth. III, 1205, 1823. Elanoides leucurus, Vieill. Enc. Méth. III, 1205, 1823. Elanus leucurus, Bonap. Eur. & N. Am. Birds, p. 4, 1838; Consp. Av. p. 22, 1850.—Gray, Gen. B. fol. sp. 4, 1844; List B. Brit. Mus. p. 46, 1844.—Rich. Schomb. Reis. Brit. Guiana, p. 735.—Cass. B. Cal. & Tex. p. 106, 1854; Birds N. Am. 1858, 37.—Kaup, Monog. Falc. Cont. Orn. 1850, p. 60.—Heerm. P. R. R. Rept. VII, 31, 1857.—Coop. & Suck. P. R. R. Rept. XII, ii, 149, 1860.—Coues, Prod. Orn. Ariz. p. 12, 1866.—Strickl. Orn. Syn. I, 138, 1855.—Gray, Hand List, I, 28, 1869. Falco melanopterus, Bonap. Journ. Ac. Phil. V, 28; Ann. Lyc. N. Y. II, 31; Isis, 1832, p. 1137. Milvus dispar, Less. Man. Orn. I, 99, 1828. Falco dispar, Bonap. Am. Orn. pl. xi, f. 1, 1825; Ann. Lyc. N. Y. II, 435.—Aud. Am. B. pls. cccli, ccclvii; Orn. Biog. IV, 367, 1831.—Temm. pl. cl. 319 (Juv.).—James. (Wils.) Am. Orn. IV. 13, 1831. Elanus dispar, Cuv. Reg. An. (ed. 2), I, 334, 1829.—Less. Tr. Orn. p. 72, 1831.—Jard. (Wils.) Am. Orn. III, 378, 1832.—Bridg. Proc. Zoöl. Soc. pt. ii, p. 109; Ann. Nat. Hist. XIII, 500.—Aud. Syn. B. p. 13, 1831.—Brew. (Wils.) Synop. p. 685, 1852.—Nutt. Man. p. 93, 1833. E. leucurus, Brewer, Oölogy.

Sp. Char. Adult. Upper surface, including occiput, nape, interscapulars, scapulars, rump, upper tail-coverts, and wings (except lesser and middle coverts), soft, delicate, rather light bluish-cinereous, becoming gradually white on anterior portion of the head above. Rest of the head, with the tail, lining of the wing, and entire lower parts, pure white, sometimes with a very faint tinge of pale pearl-blue, laterally beneath; two middle tail-feathers ashy, but much lighter than the rump; shafts of tail-feathers black, except toward ends. Bristly loral feathers (forming ante-orbital spot, extending narrowly above the eye), a very large patch on the shoulder, covering lesser and middle wing-coverts, and large quadrate spot on under side of wing (on first row of primary coverts), deep black. Under side of primaries deep cinereous (darker than outer surface); under surface of secondaries nearly white. Second quill longest; third scarcely shorter (sometimes equal, or even longest); first longer than fourth. Tail slightly emarginated, the longest feather (next to outer) being about .50 longer than the middle, and .60 (or more) longer than the lateral, which is shortest.

Male. Wing, 12.50; tail, 7.10; tarsus, 1.20; middle toe, 1.15.

Female. Wing, 12.80; tail, 7.10; tarsus, 1.45; middle toe, 1.35.

Specimens not perfectly adult have the primary coverts, secondaries, and inner primaries, slightly tipped with white.

Still younger individuals have these white tips broader, the tail more ashy, and the upper parts with numerous feathers dull brown, tipped narrowly with white; the breast with sparse longitudinal touches of brownish.

Young (♀, 48,826, Santiago, Chile, May, 1866; Dr. Philippi). Occiput and nape thickly marked with broad streaks of dusky, tinged with rusty; scapulars umber-brown, tipped with rusty; all the feathers of wings narrowly tipped with white; tail-feathers with a subterminal irregular bar of dark ashy; breast tinged with rufous, and with badly defined cuneate spots of deeper rusty. Wing, 12.25; tail, 7.50. (Perhaps not the youngest stage.)

Hab. Tropical and warm temperate America (except the West Indies), from Chile and Buenos Ayres to Florida, South Carolina, Southern Illinois, and California; winter resident in latter State.

Localities: Xalapa (Scl. 1857, 201); Guatemala (Scl. Ibis, I, 220); Brazil (Pelz. Orn. Bras. I, 6); Buenos Ayres (Scl. & Salv. 1869, 160); Venezuela (Scl. & Salv. 1869, 252).

Specimens are from Santa Clara, California, Fort Arbuckle, Mirador and Orizaba, Mexico, Chile, and Buenos Ayres; from all points the same bird.

This species presents a very close resemblance to the E. melanopterus of Europe, and the most evident specific difference can only be detected by raising the wing, the under side of which is quite different in the two, there being in the European bird no trace whatever of the black patch so conspicuous in the American species. The primaries, also, on both webs are lighter ash, while the ash of the upper parts in general is darker than in leucurus and invades more the head above, the forehead merely approaching white. The tail is more deeply emarginated, and the proportions of the primaries are quite different, the second being much longer than the third, and the first nearly as long as the second, far exceeding the third, instead of being about equal to the fourth. In the melanopterus, too, the black borders the eye all round, extending back in a short streak from the posterior angle, instead of being restricted to the anterior region and upper eyelid, as in leucurus.

A specimen of “E. axillaris” from Australia (13,844, T. R. Peale) appears, except upon close examination, to be absolutely identical in all the minutiæ of coloration, and in the wing-formula, with E. leucurus; and differs only very slightly in the measurements of bill and feet, having these proportionally larger, as will be seen from the table. Another (32,577, H. Mactier Warfield) has the upper parts so pale as to be nearly white.

A young specimen of E. axillaris differs from that of E. leucurus as follows: the occiput, nape, and dorsal region are stained or overlaid by dull ashy-rufous, instead of dark brownish-ashy; more blackish on the head. No other differences are appreciable.

A very characteristic distinction between leucurus and axillaris is seen in the coloration of the inner webs of the secondaries: in the former, they are abruptly lighter than the outer webs, often pure white, in very striking contrast to the deep ash of the outer surface; in the latter, both webs are of about the same shade of ash, which is much paler than in the other race. Occasional specimens of leucurus occur, however, in which there is little difference in tint between the two webs.

LIST OF SPECIMENS EXAMINEDNational Museum, 10; Philadelphia Academy, 2; New York Museum, 2; Boston Society, 4; Cambridge Museum, 2; Cab. G. N. Lawrence, 2; Coll. R. Ridgway, 2. Total, 24.

Habits. The Black-shouldered Hawk is a southern, western, and South American species. On the Pacific it is found to occupy a much more northern range of locality than in the eastern States, where it is not found above South Carolina and Southern Illinois. Specimens have been taken near San Francisco in midwinter.

Several individuals of this species, precisely identical with others from the United States, were taken by Lieutenant Gilliss, in the astronomical expedition to Chile. Its range in South America does not appear to be confined, as was supposed, to the western coast, as specimens are recorded by Von Pelzeln as having been obtained by Natterer in Brazil, at Ytarare, Irisanga, and San Joaquin, on the Rio Branco, in August, February, and January. These were taken on the heights. They are also found in the countries of Mexico and Central America.

Elanus leucurus.

This species has been met with in South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas, and probably occurs also in New Mexico and Arizona. Dr. Gambel describes them as very abundant in California, where they are said to be familiar in their habits, and breed in clumps of oaks, in the immediate vicinity of habitations. Dr. Heermann also speaks of them as common in that State. But neither of these naturalists appears to have met with their nests or eggs. It is not mentioned either as a bird of Cuba or Jamaica by Mr. Lembeye, Dr. Gundlach, Mr. Gosse, or Mr. March.

Dr. Cooper speaks of this bird as a beautiful and harmless species, quite abundant in the middle districts of California, remaining in large numbers, during winter, among the extensive tulé marshes of the Sacramento and other valleys. He did not meet with any during winter at Fort Mohave, nor do they seem to have been collected by any one in the dry interior of that State, nor in the southern part of California. He has met with them as far north as Baulines Bay, and near Monterey, but always about streams or marshes. Their food consisted entirely of mice, gophers, small birds, and snakes, and they were not known to attack the inmates of the poultry-yard.

Bonaparte, who first introduced the species into our fauna, received his specimen from East Florida. The late Dr. Ravenel obtained one living near Charleston, S. C., which he kept several days without being able to induce it to eat. Mr. Audubon received another, taken forty miles west of Charleston by Mr. Francis Lee. This gentleman, as quoted by Audubon, mentioned its sailing very beautifully, and quite high in the air, over a wet meadow, in pursuit of snipe. It would poise itself in the manner of the common Sparrow Hawk, and, suddenly closing its wings, plunge towards its prey with great velocity, making a peculiar sound with its wings as it passed through the air. Its cries on being wounded resembled those of the Mississippi Kite. It was so shy that Mr. Lee was only able to approach it on horseback.