полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 3

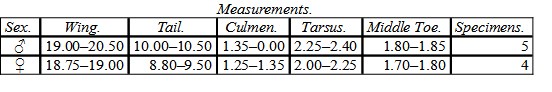

P. haliætus. Wing, 15.20–21.50; tail, 7.00–11.11; culmen, 1.20–1.40; tarsus, 2.00–2.15; middle toe, 1.60–2.00. Second or third quills longest. Above clear dark grayish-brown, inclining to brownish-black, plain, or variegated with white. Tail brownish-gray (the inner webs almost entirely white), narrowly tipped with white, and crossed by about six or seven nearly equal bands of dusky-black. Head, neck, and entire lower parts, snowy-white; the breast with or without brown spots or wash. A dusky stripe on side of head (from lores across the ear-coverts), and top of head more or less spotted, or streaked, with the same. Adult. Upper parts plain. Young. Feathers of the upper parts bordered terminally with white. Sexes alike (?).

Wing, 17.00–20.50; tail, 7.00–10.00; culmen, 1.20–1.45; tarsus, 1.95–3.15; middle toe, 1.50–1.90. Second or third quills longest (in eighteen specimens from Europe and Asia). First longer than fifth. Breast always (?) spotted with brownish, or uniformly so; top of head with the black streaks usually predominating. Tail with six to seven narrow black bands, continuous across both webs. Hab. Northern Hemisphere of the Old World … var. haliætus.68

Wing, 17.50–21.50; tail, 8.70–10.50; culmen, 1.25–1.40; tarsus, 2.00–2.40; middle toe, 1.70–2.00. Second and third quill longest. Breast often entirely without spots; top of head and nape usually with dark streaks predominating. Tail with six to seven narrow black bands, continuous across both webs. Hab. Northern Hemisphere of the New World … var. “carolinensis.”

Wing, 17.50–19.50; tail, 9.00–10.00; culmen, 1.25–1.40; tarsus, 2.10; middle toe, 1.70–1.95. Third quill longest, but second just perceptibly shorter (eight specimens, including Gould’s types). Breast with the markings sometimes (in two out of the eight examples) reduced to sparse shaft-streaks, but never (?) entirely immaculate. Top of the head with the white streaks usually predominating, sometimes (in three out of the eight specimens) immaculate white (the occiput, however, always with a few streaks). Tail with six to seven white bands on the inner webs, which (according to Kaup) do not touch the shaft. Hab. Australia … var. “leucocephalus.”69

Pandion haliætus, var. carolinensis (Gmel.)FISH-HAWK; AMERICAN OSPREYFalco carolinensis, Gmel. Syst. Nat. p. 263, 1789.—Daud. Tr. Orn. II, 69, 1800. Pandion carolinensis, Bonap. List, pt. iii, 1838; Consp. Av. p. 16.—Strickl. Orn. Syn. I, 64, 1855.—Aud. Birds Am. pl. lxxxi, 1831.—Cass. Birds Cal. & Tex. p. 112, 1854.—Brewer, Oölogy, 1857, p. 53, pl. iii, fig. 33, 34.—Newb. P. R. R. Rept. VI, iv, 75, 1857.—Heerm. VII, 21, 1857.—De Kay, Zoöl. N. Y. II, 8, pl. vi, fig. 18.—Cass. Birds N. Am. 1858, p. 44.—Coop. & Suck. P. R. R. Rept. XII, ii, 153, 1860.—Coues, Prod. Orn. Ariz. 1866, p. 13.—Gray, Hand List, I, 15, 1869.—Max. Cab. Journ. VI, 1858, 11.—Lord, Pr. R. A. I. IV, 1864, 110 (Brit. Columb.; nesting).—Fowler, Am. Nat. II, 1868, 192 (habits). Falco cayennensis, Gmel. Syst. Nat. p. 263, 1789.—Daud. Tr. Orn. II, p. 69, 1800. Falco americanus, Gmel. Syst. Nat. p. 257.—Lath. Index Orn. p. 13, 1790; Syn. I, 35, 1781; Gen. Hist. I, 238, 1821.—Daud. Tr. Orn. II, 50.—Shaw, Zoöl. VII, 88. Aquila americana, Vieill. Ois. Am. Sept. I, pl. iv, 1807. Pandion americanus, Vieill. Gal. Ois. pl. ii, 1825.—Vig. Zoöl. Journ. I, 336.—Swains. Classif. B. II, 207, 1837. Aquila piscatrix, Vieill. Ois. Am. Sept. I, pl. iv, 1807. Accipiter piscatorius, Catesby, Carolina, I, pl. ii, 1754. A. falco piscator antillarum, Briss. Orn. I, 361, 1760. A. falco piscator carolinensis, Briss. Orn. I, 362. Pandion haliætus, Rich. Faun. Bor. Am. II, 20, 1831.—Jard. (Wils.) Am. Orn. II, 103, 1832.—James. (Wils.) Am. Orn. I, 38, 1831.—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 415, 1831.—Gray, List B. Brit. Mus. p. 22, 1844. ? Pandion fasciatus, Brehm, Allgem. deutsch. Zeitung, II, 1856, 66 (St. Domingo).

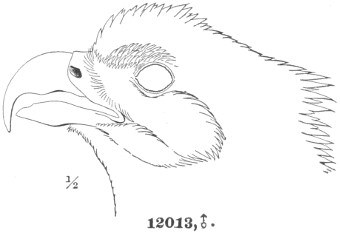

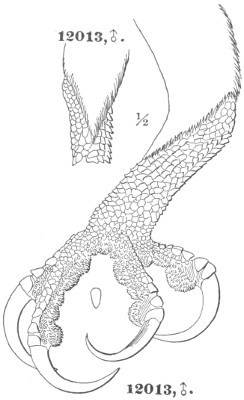

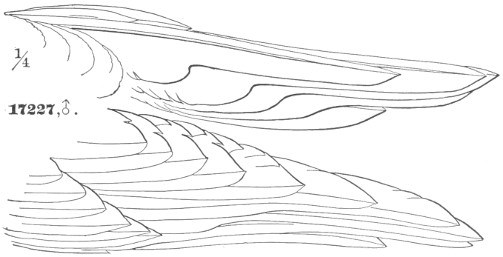

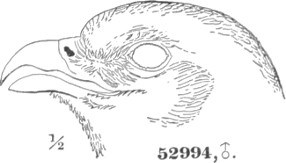

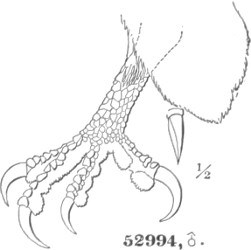

Sp. Char. Adult male (17.227, San José, Lower California, December 15, 1859; J. Xantus). Upper surface dark vandyke-brown, with a faint purplish cast; quills black. Every feather with a conspicuous, sharply defined terminal crescent of pure white. Tail brownish-drab, narrowly tipped with white, and crossed with seven (one concealed) regular bands of dusky; inner webs almost wholly white, the black bands sharply defined and continuous; shafts entirely white. Ground-color of the head, neck, and entire lower parts, pure white; a broad stripe from the eye back across upper edge of the ear-coverts to the occiput brownish-black; white head also sparsely streaked with blackish, these streaks suffusing and predominating medially; nape faintly tinged with ochraceous, and sparsely streaked. Breast with large cordate spots of brown, fainter than that of the back, a medial spot on each feather, the shaft black; rest of lower parts immaculate. Lining of the wing white, strongly tinged with ochraceous; the brown of the outer surface encroaching broadly over the edge. Under primary-coverts with broad transverse spots or bars; under surface of primaries grayish-white anterior to the emargination irregularly mottled with grayish; axillars immaculate. Wing-formula, 2=3, 4–1, 5. Wing, 20.00; tail, 8.80; culmen, 1.35; tarsus, 2.15–1.10; middle toe, 1.90; outer, 1.75; inner, 1.40; posterior, 1.15; posterior outer and inner claws of equal length, each measuring 1.20 (chord); middle, 1.15. “Iris yellow; feet greenish-yellow.”

Adult female (290, S. F. Baird’s Collection, Carlisle, Pa., April 17, 1841). Dark brown of the upper surface entirely uniform, there being none of the sharply defined white crescents so conspicuous in the male.70 Tail brown to its tip, the dusky bands obscure, except on inner webs. On the top of the head, the dusky is more confined to a medial stripe. Pectoral spots smaller, less conspicuous. Under surface of primaries more mottled with grayish. Wing-formula, 3, 2–4–1, 5. Wing, 20.50; tail, 9.15; culmen, 1.35; tarsus, 2.15; middle toe, 1.70.

12013, ♂. ½

12013, ♂. ½

17227, ♂. ¼

Pandion carolinensis.

Hab. Whole of North America, south to Panama; N. Brazil; Trinidad, Cuba, and other West India Islands.

Localities: Belize (Scl. Ibis, I, 215); Cuba (Cab. Journ. II, lxxx, nests; Gundl. Repert. Sept. 1865, 1, 222); Bahamas (Bryant, Pr. Bost. Soc. VII, 1859); Panama (Lawr. VIII, 63); Trinidad (Taylor, Ibis, 1866, 79); Arizona (Coues, Pr. A. N. S. 1866, 49); N. Brazil (Pelz. Orn. Bras. I, 4).

In eight out of twelve North American adult specimens, there is but the slightest amount of spotting on the breast; in two of these (4,366, Puget Sound, and 12,014, Oregon), none whatever; in 17,228 (♂, Cape St. Lucas), 2,512 (♂ S. F. B. Carlisle, Pa.), 34,065 (♀, Realejo, Central America), and 5,837 (Fort Steilacoom), there is just a trace of these spots.

The specimens described are those having the breast most distinctly spotted. Specimens vary, in length of wing, from 17.50 to 20.50. There appears to be no sexual difference in size.

The distinctness or identity of the European and North American Ospreys can only be determined by the comparison of a very large series; this we have not been able to do, and although it is our belief that they should not be separated, the impressions received from a close inspection of the specimens before us (twenty-seven American and eighteen European) seem to indicate the propriety of distinguishing them as races.

The male of the pair described appears to be perfectly identical, in all respects except size, with a very perfect, finely mounted European male; indeed, the only discrepancy is in the size, the wing of the European bird being only nineteen inches, instead of twenty inches as in the American. The female, however, differs from European females in having the brown on the breast in the form of detached faint spots, instead of a continuous grayish-brown wash, more or less continuous.

The types of our descriptions are the only specimens of the American series which show even an approach to the amount of spotting on the breast constant in birds from Europe.

The American bird, as indicated by the series before us, would seem to be rather the larger; for the European specimens measure uniformly about an inch less than the American in length of the wing.

In all the American specimens, of both sexes, the shafts of the tail-feathers are continuously white, while in the European they are clear white only at the roots or for the basal half.

While, in consideration of the above facts, I am for the present compelled to recognize the American Pandion under the distinctive name of carolinensis, I may say, that, if any European birds occur with the breast immaculate,—no matter what the proportion of specimens,—I shall at once waive all claims to distinctness for the American bird.

LIST OF SPECIMENS EXAMINEDNational Museum, 7; Philadelphia Academy, 3; New York Museum, 1 (Brazil); Boston Society, 6; Museum Cambridge, 9; Cab. G. N. Lawrence, 1; Coll. R. Ridgway, 1. Total, 28.

Second and third quills longest; first shorter or longer than fifth.

Habits. The Fish Hawk of North America, whether we regard it as a race or a distinct species from that of the Old World fauna, is found throughout the continent, from the fur regions around Hudson’s Bay to Central America. According to Mr. Hill, it is seen occasionally in Jamaica, and, as I learn by letter from Dr. Gundlach, is also occasionally met with in the island of Cuba; but it is not known to breed in either place. Dr. Woodhouse, in his report of the expedition to the Zuñi River, speaks of this Hawk as common along the coasts of Texas and California. Dr. Heermann mentions it as common on the borders of all the large rivers of California in summer; and Dr. Gambel also refers to it as abundant along the coast of that State, and on its rocky islands, in which latter localities it breeds. I am not aware that it has ever been found farther south than Texas, on the eastern coast. On the Pacific coast it appears to have a more extended distribution both north and south, but nowhere to be so abundant as on certain parts of the Atlantic coast.

Pandion haliætus (European specimen).

Mr. Bischoff obtained this species about Sitka, where he found it breeding, and took its eggs; and Mr. Dall procured several specimens near Nulato in May, 1867, and in 1868. They were not uncommon, frequenting the small streams, and were summer visitors, returning to the same nest each season. Colonel Grayson found it breeding as far south as the islands of the Tres Marias, in latitude 31° 30′ north. The nest was on the top of a giant cactus. Mr. Xantus describes it as breeding on the ground at Cape St. Lucas.

In the interior it was met with by Richardson, but its migrations do not appear to reach the extreme northern limits of the continent. That observing naturalist saw nothing of this bird when he was coasting along the shores of the Arctic Sea, nor did Mr. Hearne find it on the barren grounds north of Fort Churchill. Its eggs were collected on the Mackenzie River by Mr. Ross, and on the Yukon by Messrs. Lockhart, Sibbiston, McDougal, and Jones. At Fort Yukon, Mr. Lockhart found it nesting on a high tree (S. I. 15,676).

On the Atlantic coast it is found from Labrador to Florida, with the exception of a portion of Massachusetts around Boston, where it does not breed, and where it is very rarely met with. It is most abundant from Long Island to the Chesapeake, and throughout this long extent of coast is very numerous, often breeding in large communities, to the number of several hundred pairs. Away from the coast it is much less frequent, but is occasionally met with on the banks of the larger rivers and lakes, and in such instances usually in solitary pairs. Dr. Hayden found it nesting in the Wind River Mountains on the top of a large cottonwood tree.

Mr. Allen reports this species as abundant everywhere in Florida, and as especially so around the lakes of the Upper St. Johns, where it commences nesting in January. At Lake Monroe he counted six nests from a single point of view. It is said by fishermen to occur on the coast of Labrador, but it is not cited as found there by Mr. Audubon, nor is it so given by Dr. Coues. It is, however, very common on the coast of Nova Scotia, breeding in the vicinity of most of the harbors. It is given by Mr. Boardman as common near Calais, where it arrives about the 10th of April, and remains until the middle of September. It is found along the whole coast more or less abundantly, especially near the heads of the numerous estuaries.

In Central America it is cited by Salvin as occurring abundantly on both the coast regions, and is particularly common about Belize, where it is believed to breed. It is said by Mr. Newton to be found on the island of St. Croix at all times except during the breeding-season. It was also occasionally seen at Trinidad by Mr. E. C. Taylor.

The Fish Hawk appears to subsist wholly on the fish which it takes by its own active exertions, plunging for them in the open deep, or catching them in the shallows of rivers where the depth does not permit a plunge. Its abundance is measured somewhat by its supply of food; and in some parts of the country it is hardly found, in others it appears in solitary pairs, and again in a few districts it is quite gregarious.

The American Fish Hawk is migratory in its habits, leaving our coasts early in the fall of the year, and returning soon after the close of the winter. Sir John Richardson states that the time of its arrival in the fur regions is as early as April, and on the coast it has been noticed in the middle of March. It breeds on the coast of Nova Scotia late in June, on that of Maine earlier in the same month, in New Jersey and Maryland in May, and still earlier in California.

It is said to arrive on the New Jersey coast with great regularity about the 21st of March, and to be rarely seen there after the 22d of September. It not unfrequently finds, on its first arrival, the ponds, bays, and estuaries ice-bound, and experiences some difficulty in procuring food. Yet I can find no instance on record where our Fish Hawk has been known to molest any other bird or land-animal, to feed on them, though their swiftness of flight, and their strength of wing and claws, would seem to render such attacks quite easy. On their arrival the Fish Hawks are said to combine, and to wage a determined war upon the White-headed Eagles, often succeeding by their numbers and courage in driving them temporarily from their haunts. But they never attack them singly.

The Fish Hawk nests almost invariably on the tops of trees, and this habit has been noticed in all parts of the country. It is not without exceptions, but these are quite rare. William H. Edwards, Esq., found one of their nests constructed near West Point, New York, on a high cliff overhanging the Hudson River. The trees on which their nests are built are not unfrequently killed by their excrement or the saline character of their food and the materials of their nest. The bird is bold and confiding, often constructing its nest near a frequented path, or even upon a highway. Near the eastern extremity of the Wiscasset (Me.) bridge, and directly upon the stage-road, a nest of this Hawk was occupied several years. It was upon the top of a low pine-tree, was readily accessible, the tree being easily climbed, and was so near the road that, in passing, the young birds could frequently be heard in their nest, uttering their usual cries for food.

The nests are usually composed externally of large sticks, often piled to the height of five feet, with a diameter of three. In a nest described by Wilson, he found, intermixed with a mass of sticks, corn-stalks, sea-weed, wet turf, mullein-stalks, etc., the whole lined with dry sea-grass (Zostera marina), and large enough to fill a cart and be no inconsiderable load for a horse.

When the nest of this Hawk is visited, especially if it contain young, the male bird will frequently make violent, and sometimes dangerous, attacks upon the intruder. In one instance, in Maine, the talons of one of these Hawks penetrated through a thick cloth cap, and laid bare the scalp of a lad who had climbed to its nest, and very nearly hurled him to the ground. A correspondent quoted by Wilson narrates a nearly similar instance of courageous and desperate defence of the young. They are very devoted in their attentions to their mates, and supply them with food while on the nest. Wilson relates a touching instance of this devotion, where a female that had lost one leg, and was unable to fish for herself, was abundantly supplied by her mate.

In some localities the Fish Hawk nests in large communities, as many as three hundred pairs having been observed nesting on one small island. When a new nest is to be constructed, the whole community has been known to take part in its completion. They are remarkably tolerant towards smaller birds, and permit the Purple Grakle (Quiscalus purpureus) to construct its nests in the interstices of their own. Wilson observed no less than four of these nests thus clustered in a single Fish Hawk’s nest, with a fifth on an adjoining branch.

The eggs of the Fish-Hawk are usually three in number, often only two, and more rarely four. They are subject to great variations as to their ground-color, the number, shade, and distribution of the blotches of secondary coloring with which they are marked, and also as to their size and shape. Their ground-color is most frequently a creamy-white, with a very perceptible tinge of red. This varies, however, from an almost pure shade of cream, without any admixture, to so deep a shade of red that white ceases to be noticeable. Their markings are combinations of an almost endless variation of shades of umber-brown, a light claret-brown, an intermingling of both these shades, with occasional intermixtures of purplish-brown. They vary in length from 2.56 to 2.24 inches, and in breadth from 1.88 to 1.69 inches. It would be impossible to describe with any degree of preciseness the innumerable variations in size, shape, ground-color, or shades of markings, these eggs present. They all have a certain nameless phase of resemblance, and may be readily distinguished from any other eggs except those of their kindred. There are, however, certain shades of wine-colored markings in the eggs of the Fish Hawk of Europe, and also in that of Australia, that I have never noticed in any eggs of the American bird; but that this peculiarity is universal I am not able to say. The smallest egg of the carolinensis measures 2.31 by 1.62 inches; the largest, 2.56 by 1.88.

The European egg is smaller than the American, is often, but not always, more spherical, and is less pointed at the smaller end. Among its varieties is one which is quite common, and is very different from any I have ever observed among at least five hundred specimens of the American which I have examined.

An Osprey’s egg in my collection, taken near Aarhuus, in Denmark, by Rev. H. B. Tristram, of Castle Eden, England, measures only 2.12 inches in length,—shorter by a fourth of an inch than the smallest American,—in breadth 1.62 inches; its ground-color is a rich cream, with a slight tinge of claret, and it is marked over its whole surface with large blotches of a beautifully deep shade of chocolate.

In their habits the European and the American birds seem to present other decided differences. The American is a very social bird, often living in large communities during the breeding-season. The European is found almost invariably in solitary pairs, and frequents fresh water almost exclusively. The American, though found also on large rivers and lakes, is much the most abundant on the sea-shore. The European bird rarely builds on trees, the American almost always. The latter rarely resorts to rocky cliffs to breed, the European almost uniformly do so. There is no instance on record of the American species attacking smaller birds or inferior land animals with intent to feed on them. The European species is said to prey on Ducks and other wild-fowl.

Genus NAUCLERUS, Vigors

Nauclerus, Vig. 1825. (Type, Falco furcatus, Linn.; F. forficatus, Linn.)

Elanoides, Gray, 1848. (Same type.)

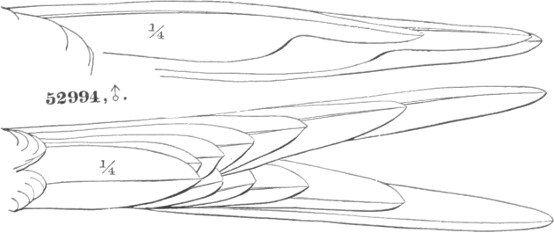

Gen. Char. Form swallow-like, the tail excessively lengthened and forked, and the wings extremely long. Bill rather small, and narrow; commissure faintly sinuated; upper outline of the lower mandible very convex, the depth of the mandible at the base being only about half that through the middle; gonys drooping terminally, nearly straight. Side of the head densely feathered close up to the eyelids. Nostril ovoid, obliquely vertical. Feet small, but robust; tarsus about equal to middle toe, covered with large, very irregular scales; toes with transverse scutellæ to their base; claws short, but strongly curved; grooved beneath, their edges sharp. Second or third quill longest; first shorter than, equal to, or longer than, the fourth; two outer primaries with inner webs sinuated. Tail with the outer pair of feathers more than twice as long as the middle pair.

The genus contains but a single species, the N. forficatus, which is peculiarly American, belonging to the tropical and subtropical portions on both sides of the equator. The species is noted for the elegance of its form and the beauty of its plumage, as well as for the unsurpassed easy gracefulness of its flight. It has no near relatives in the Old World, though the widely distributed genus Milvus represents it in some respects, while the singular genus Chelictinia, of Africa, resembles it more closely, but is much more intimately related to Ictinia and Elanus.

52994, ♂. ½

52994, ♂. ½

52994, ♂. ¼ ¼

Nauclerus forficatus.

Species

N. forficatus. Head, neck, entire lower surface, and band across the rump, immaculate snowy-white; upper surface plain polished blackish, with varying lights of dark purplish-bronze (on the back and shoulders) and bluish-slaty, with a green reflection in some lights. Young, with dusky shaft-streaks on the head and neck, and the feathers of the upper parts margined with white. Wing, 15.40–17.70; tail, 12.50–14.50; culmen, .70–.80; tarsus, 1.00–1.30; middle toe, 1.15–1.20. Hab. The whole of tropical, subtropical, and warm-temperate America. Accidental in England.

Nauclerus forficatus, (Linn.) RidgwaySWALLOW-TAILED HAWK; FORK-TAILED KITEAccipiter cauda furcata, Catesby, Carolina, I, pl. iv, 1754. Falco forficatus, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 89, 1758. Falco furcatus, Linn. Syst. Nat. p. 129, 1766.—Penn. Arct. Zoöl. p. 210, No. 108, pl. x.—Gmel. Syst. Nat. p. 262. Nauclerus forficatus, Ridgway, P. A. N. S. Phil. Dec. 1870, 144.—Daud. Tr. Orn. II, 152.—Shaw, Nat. Misc. pl. cciv; Zoöl. VII, 107.—Wils. Am. Orn. pl. li, f. 3, 1808.—Aud. Birds Am. pl. 72, 1831; Orn. Biog. I, 368; V, 371.—Bonap. Ann. Lyc. N. Y. II, 31; Isis, 1832, 1138. Milvus furcatus, Vieill. Ois. Am. Sept. pl. x, 1807. Elanoides furcatus, Gray, List B. Brit. Mus. p. 44, 1844.—Strickl. Orn. Syn. I, 141, 1855.—Owen, Ibis, II, 1860, 240 (habits). Nauclerus furcatus, Vig. Zoöl. Journ. II, 387; Isis, 1830, p. 1043.—Less. Man. Orn. I, 101; Tr. Orn. p. 73.—Swains. Classif. B. I, 312; II, 210, 1837.—Bonap. List, p. 4; Cat. Ucc. Eur. p. 20; Consp. Av. p. 21.—Gould, B. Eur. pl. xxx.—Aud. Synop. p. 14, 1839.—Rich. Schomb. Reis. Brit. Guian. p. 735.—De Kay, Zoöl. N. Y. II, p. 12, pl. vii, f. 15.—Gray, Gen. B. fol. sp. 1, pl. ix, f. 9; Gen. & Subgen. Brit. Mus. p. 6.—Brew. (Wils.) Synop. Am. Orn. p. 685.—Woodh. Sitgr. Exp. Zuñi & Colorado, p. 60.—Kaup, Monog. Falconidæ, Cont. Orn. 1850, p. 57.—Brewer, Oölogy, I, 1857, 38.—Cass. Birds N. Am. 1858, 36.—Coues, Prod. Orn. Ariz. 1866, p. 12.—Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 525 (Texas, nesting).—Gray, Hand List, I, 27, 1869. Elanus furcatus, Vig. Zoöl. Journ. I, 340.—Steph. Zoöl. XIII, pl. ii, p. 49.—Cuv. Règ. An. (ed. 2), I, p. 334.—James. (Wils.) Am. Orn. I, 75.—Jard. (Wils.) Am. Orn. II, 275.—Jard. Orn. Eur. p. 29.—Nutt. Man. p. 94. Accipiter milvus carolinensis, Briss. Orn. I, 418, 1760. Elanoides yetapa, Vieill. Enc. Méth. III, 1205, 1823.