полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 3

Mr. Audubon states that the flight of this species is never protracted. It seldom flies far at a time; a few hundred yards are all the distance it usually goes before alighting. It rarely sails long on the wing at a time; a half-hour is its utmost extent. In pursuing a bird, it flies with great rapidity, but never with the speed of the Sharp-shinned and other Hawks. Its cry is so similar to that of the Kestrel of Europe that it might be readily mistaken for it but for its stronger intonation. At times it gives out these notes as it perches, but they are principally uttered while on the wing. Mr. Audubon has heard them imitate the feeble cries of their offspring, when these have left the nest and are following their parents.

The young birds, when they first appear, are covered with a white down. They grow with great rapidity, and are soon able to leave their nest, and are well provided for by their parents until they are able to take care of themselves. They feed at first on grasshoppers and crickets.

At Denysville, Me., these Hawks were observed to attack the Cliff Swallows, while sitting on their eggs, deliberately tearing open their covered nests, and seizing their occupants for their prey.

In winter, these birds, for the most part, desert the Northern and Middle States, but are resident south of Virginia. They can be readily tamed, especially when reared from the nest. Mr Audubon raised a young Hawk of this species, which continued to keep about the house, and even to fly to it for shelter when attacked by some of its wilder kindred, and never failed to return at night to roost on its favorite window-shutter. It was finally killed by an enraged hen, whose chickens it attempted to seize.

This Hawk constructs no nest, but makes use of hollow trees, the deserted hole of a Woodpecker, or even an old Crow’s nest. Its eggs are usually as many as five in number, and Mr. Audubon once even met with seven in a single nest. The ground of the eggs is usually a dark cream-color or a light buff. In their markings they vary considerably. Five from a nest in Maryland were covered throughout the entire surface with small blotches and dottings of a light brown, at times confluent, and, except in a single instance, not more frequent at the larger end than the smaller. The contents of a nest obtained by Mr. Audubon on the Yellowstone River had a ground-color of a light buff, nearly unspotted, except at the larger end, with only a few large blotches and splashes of a deep chocolate. In others, interspersed with the light-brown markings are a few of a much deeper shade. In some, the eggs are covered with fine markings of buff, nearly uniform in size and color; and others again are marked with lines and bolder dashes of brown, of a distinctly reddish shade, over their entire surface, and often so thickly as nearly to conceal the ground. The eggs are nearly spherical. The average length is 1.38 inches by a breadth of 1.13. They are subject to variation in size, but are uniform as to shape. They range in length from 1.48 to 1.32 inches, and in breadth from 1.08 to 1.20 inches.

The eggs of Tinnunculus sparveroides, from Cuba, and of var. cinnamominus from Chile, differ in size and markings from those of North American birds. Their ground-color is much whiter, is freer from markings which have hardly any tinge of rufous, but are more of a yellowish-brown. The Cuban egg measures 1.28 by 1.08 inches; the Chilian, 1.25 by 1.08.

Genus POLYBORUS, Vieillot

Polyborus, Vieill. 1816. (Type, Falco brasiliensis, Gmelin. P. tharus, Molina.)

Caracara, Cuvier, 1817. (Same type.)

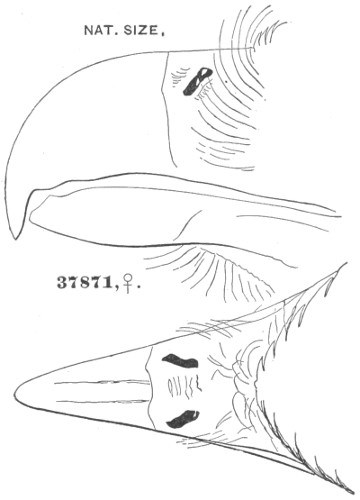

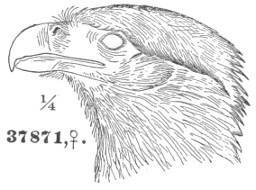

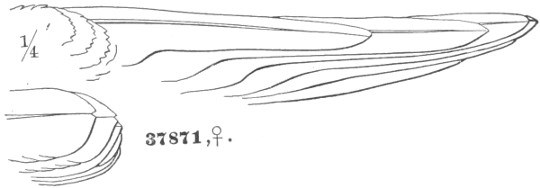

Gen. Char. General aspect somewhat vulturine, but bearing and manners almost gallinaceous. Neck and legs very long. Bill very high and much compressed, the commissure very straight and regular, and nearly parallel with the superior outline; cere very narrow, its anterior outline vertical and straight. Nostril very small, linear, obliquely vertical, its upper end being the posterior one; situated in the upper anterior corner of the cere. Lateral and under portions of the head naked and scantily haired, the skin bright-colored (reddish or yellow in life). Occipital feathers elongated. Wings and tail long, the latter rounded; five outer quills with inner webs sinuated; third to the fourth longest; first shorter than the sixth, sometimes shorter than the seventh. Feet almost gallinaceous, the tarsus nearly twice as long as the middle toe, but stout; outer toe longer than the inner; posterior toe much the shortest; claws long, but slender, weakly curved, and obtuse. Tarsus with a frontal series of large transverse scutellæ, the lower fourth to sixth forming a single row, the others disposed in two parallel series of alternating plates; the other parts covered by smaller hexagonal scales.

37871, ♀. nat. size.

37871, ♀. ¼

37871, ♀. ¼

Wing and tail.

37871, ♀. ¼

Polyborus auduboni.

This well-marked genus contains but a single species, the P. tharus, Mol., which extends its range over the whole of tropical and subtropical America, exclusive of some of the West India Islands. North and south of the Isthmus it is modified into geographical races, the southern of which is var. tharus, Mol., and the northern var. auduboni, Cass.

The closely related genera Phalcobænas, Milvago, Ibycter, and Daptrius are peculiar to South America and the southern portion of Middle America, most of them being represented by two or more species. They all form a well-marked and peculiarly American group, for which I shall retain Schlegel’s term Polybori.

Their habits are quite different in many respects from those of other Falconidæ, for they combine in many respects the habits of the gallinaceous birds and those of the Vultures. They are terrestrial, running and walking gracefully, with the exception of the species of Ibycter and Daptrius, which are more arboreal than the others, and are said also to feed chiefly upon insects, instead of carrion.

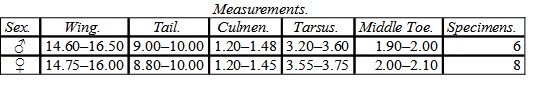

Species and RacesP. tharus. Wing, 14.50–17.70; tail, 10.00–11.00; culmen, 1.20–1.48; tarsus, 3.20–4.20; middle toe, 1.75–2.30.

Adult. Forehead, crown, occiput, back, rump, abdomen, sides, and tibiæ, and terminal zone of the tail, dull black. Neck, breast, tail-coverts, and tail, dingy whitish. Interscapulars, breast, and tail with transverse dusky bars.

Young. Blackish areas replaced by dull brown; region of the transverse bars marked, instead, with longitudinal stripes.

Adult. Whole body, with middle wing-coverts, variegated with transverse bars of black and white; tail-coverts barred. Terminal zone of the tail about 2.00 wide. Young. Longitudinal stripes over the whole head and body, except throat, cheeks, and tail-coverts; tail-coverts transversely barred. Hab. South America … var. tharus.67

Adult. Transverse bars confined to the breast and interscapulars; rest of body continuous black; tail-coverts without bars; wing-coverts unvariegated. Terminal zone of tail about 2.50 wide. Young. Longitudinal stripes confined to the breast and interscapulars; rest of the body continuous brown. Tail-coverts without bars. Hab. Middle America, and southern border of United States, from Florida to Cape St. Lucas … var. auduboni.

Polyborus tharus, var. auduboni, CassinCARACARA EAGLE; “KING BUZZARD” OF FLORIDAPolyborus auduboni, Cassin, Proc. Acad. Nat. Sc. Philad. 1865, p. 2. Polyborus vulgaris (“Vieill.”), Aud. Orn. Biog. II, 350, 1834 (not of Vieillot!). Polyborus brasiliensis (“Gmel.”), Aud. Birds Am. Oct. ed. I, 21, 1840 (not of Gmelin!). Polyborus tharus (“Mol.”) Cassin, Birds of Cal. & Tex. I, 113; 1854 (not of Molina!); Brewer, Oölogy, 1857, p. 58, pl. xi, figs. 18 & 19; Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, p. 45.—Heerm. P. R. R. Rept. VII, 31, 1857.—Coues, Prod. Orn. Ariz. p. 13, 1866.—Owen, Ibis, III, 67.—Gurney, Cat. Rapt. B. 1864, 17.—Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 329 (Texas).

Sp. Char. Adult male (12,016, Texas; Capt. McCall). Forehead, crown, occiput, and nape, wings, scapulars, rump, belly, thighs, and anal region continuous deep dull black; chin, neck, jugulum, breast, and tail-coverts (upper and lower), soiled white. Breast with numerous cordate spots of black, these growing larger posteriorly, and running in transverse series; back with transverse bars of white, which become narrower and less distinct posteriorly. Basal two-thirds of tail white, crossed by thirteen or fourteen narrow transverse bands of black, which become narrower and more faint basally; outer web of lateral feather almost entirely black; broad terminal band of the tail uniform black (2.40 inches in width); third, fourth, fifth, and sixth primaries grayish just beyond the coverts, this portion with three or four transverse bars of white. Middle portion of primaries beneath, faintly barred with white and ashy; the barred portion extending obliquely across. Third quill longest, fourth a little shorter, second shorter than fifth; first 3.60 inches shorter than longest. Wing, 16.70; tail, 9.60; tarsus, 3.40; middle toe, 2.10.

Adult female. Plumage similar; white more brownish; abdomen with indication of bars. Wing, 15.50; tail, 8.70; tarsus, 3.30; middle toe, 2.20.

Young (42,130, ♀, Mirador, Mexico; Dr. C. Sartorius). Black of adult replaced by dingy dark brown, this darkest in the hood; white and dusky regions gradually blended, the feathers of the breast being whitish, edged (longitudinally) with brown. No trace of the transverse bars, except on the tail, which is like that of the adult.

Hab. Middle America north of Darien; southern border of United States from Florida to Lower California; Cuba.

Localities: Guatemala (Scl. Ibis, I, 214); Cuba (Cab. Journ. II, lxxix; Gundl. Rept. 1865, 221, resident); ? Trinidad (Taylor, Ibis, 1864, 79); Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 329, breeds); Arizona (Coues); Costa Rica (Lawr. IX, 132); Yucatan (Lawr. 16, 207.)

LIST OF SPECIMENS EXAMINEDNational Museum, 16; Boston Society, 2; Philadelphia Academy, 4; Museum Comp. Zoöl., 1; R. Ridgway, 2. Total, 25.

Polyborus tharus, var. auduboni.

Habits. The Caracara Eagle, as this bird is called, though it seems to possess, to a large degree, the characteristics of a Vulture, and hardly any of the true aquiline nature, is found in all the extreme southern portions of the country, in Florida, Texas, Southern Arizona, and California. Audubon met with it abundantly in Florida in the winter of 1831. Mr. Boardman has seen it quite common at Enterprise, associating with the Vultures. Dr. Woodhouse, while encamped on the Rio Saltado, near San Antonio, in Texas, frequently saw the Caracaras, and always in company with the Vultures, which he says they greatly resemble in their habits, excepting that they were much more shy. He could, however, readily approach them when on horseback. Mr. Dresser also frequently encountered it in Texas in the vicinity of San Antonio, and speaks of it as abundant from the Rio Grande to the Guadaloupe, but never noticed any farther east. In Arizona, Dr. Coues says, it is not a rare bird in the southern and western portions of that Territory. Lieutenant Couch likewise describes them as exceedingly abundant from the Rio Grande to the Sierra Madre. He speaks of killing a male bird on the nest, which was in a low tree and composed of sticks. He adds that this bird destroys the Texas field-rats (Sigmodon berlandieri) in large numbers.

Dr. Heermann met with this species on the Colorado River, near Fort Yuma, in company with the Cathartes aura. He found it so shy that it was impossible to procure a specimen. He found it along the Gila River, and again met with it in Texas wherever there were settlements. At San Antonio, wherever there were slaughter-houses, he met with them in great numbers, twenty or thirty being often seen at a time.

Grayson gives the Caracara as quite abundant in the Tres Marias. Although it subsists mainly on dead animals and other offal, it is said to sometimes capture young birds, lizards, snakes, and land-crabs. It generally carries its prey in its beak; but Colonel Grayson states that he has seen it also bear off its food in its claws, as Hawks do. It walks with facility on the ground, and was often met with in the thick woods, walking about in search of snakes. Mr. Xantus found it nesting at Cape San Lucas, placing its nest on the top of the Cereus giganteus. It occurs also in the West Indies, especially in the island of Cuba, where it is known to breed. Eggs were obtained and identified by the late Dr. Berlandier, of Matamoras, in Northern Mexico, on the Rio Grande, in considerable numbers.

Mr. Salvin (Ibis, I, 214) says the Caracara is universal in its distribution in Central America, appearing equally abundant everywhere. At Duenas it was a constant resident, breeding on the surrounding hills. Its food seemed to consist largely of the ticks that infested the animals. In Honduras Mr. G. C. Taylor found them very common, quite tame, and easily shot. They feed on carrion and offal, were often seen scratching among the half-dry cow-dung, and are “a very low caste bird.” Mr. E. C. Taylor (Ibis, VI, 79) frequently saw this bird on the shores of the Orinoco. It was very tame, and generally allowed a near approach, and when disturbed did not fly far. He did not meet with it in Trinidad.

On the Rio Grande the popular name of this species is Totache, while in Chile the P. tharus is called Traro, but its more common name throughout South America is Carrancha.

According to Audubon, the flight of this bird is at great heights, is more graceful than that of the Vulture, and consists of alternate flapping and sailing. It often sails in large circles, gliding in a very elegant manner, now and then diving downwards and then rising again.

These birds feed on frogs, insects, worms, young alligators, carrion, and various other forms of animal food. Mr. Audubon states that he has seen them walk about in the water in search of food, catching frogs, young alligators, etc. It is harmless and inoffensive, and in the destruction of vermin renders valuable services. It builds a coarse, flat nest, composed of flags, reeds, and grass, usually on the tops of trees, but occasionally, according to Darwin, on a low cliff, or even on a bush.

Mr. R. Owen, who found this bird breeding near San Geronimo, Guatemala, April 2 (Ibis, 1861, p. 67), states that the nest was built on the very crown of a high tree in the plain. It was made of small branches twisted together, and had a slight lining of coarse grass. It was shallow, and formed a mass of considerable size. The eggs were four in number, and are described as measuring 2.15 inches by 1.60, having a light red ground-color, and spotted and blotched all over with several shades of a darker red.

Dr. Heermann found the nest of this species on the Medina River. It was built in an oak, and constructed of coarse twigs and lined with leaves and roots. It was quite recently finished, and contained no eggs. Mr. Dresser states that it breeds all over the country about San Antonio, building a large bulky nest of sticks, lined with small roots and grass, generally placed in a low mesquite or oak tree, and laying three or four roundish eggs, similar to those of the Honey Buzzard of Europe. He found several nests in April and through May, and was told by the rancheros that its eggs are found as late as June. The nests found in the collection of Dr. Berlandier, of Matamoras, were coarse flat structures, composed of flags, reeds, and grass. The nests, though usually built on the tops of trees, are occasionally found, according to Darwin, on a low cliff, or even on a bush. The number of the eggs is rarely, if ever, more than three or four. Four eggs, taken by Dr. Berlandier near the Rio Grande, exhibit a maximum length of 2.44 inches; least length, 2.25; average, 2.41. The diameter of the smallest egg is 1.75 inches; that of the largest, 1.88; average, 1.81. These eggs not only present the great and unusual variation in their length of nearly eight per cent, but very striking and anomalous deviations from uniformity are also noticeable in their ground-color and markings. The ground-color varies from a nearly pure white to a very deep russet or tan-color, and the markings, though all of sepia-brown, differ greatly in their shades. In some, the ground-color is nearly pure white with a slight pinkish tinge, nearly unspotted at the smaller end, and only marked by a few light blotches of a sepia-brown. These markings increase both in size and frequency, and become of a deeper shade, as they are nearer the larger end, until they become almost black, and around this extremity they form a large confluent ring of blotches and dashes of a dark sepia. Others have a ground-color of light russet, or rather white with a very slight wash of russet, and are marked over the entire surface, in about equal proportion, with irregular lines and broad dashes of dark sepia. Again, in others the ground is of the deepest russet or tan-color, and is marked with deep blotches of a dark sepia, almost black. The eggs are much more oblong than those of most birds of prey, and in this respect also show their relation to the Vultures, rather than to the Hawks or Eagles. They are pyriform, the smaller end tapers quite abruptly, and varies much more, in its proportions, from the larger extremity, than the eggs of most true Hawks.

Lieutenant Gilliss found the South American race exceedingly numerous throughout Central and Southern Chile. It was constantly met with along the roads, and wherever there was a chance of obtaining a particle of flesh or offal. At the annual slaughtering of cattle they congregate by hundreds, and remain without the corral, awaiting their share of the rejected parts. It was so tame, from not being molested, that it could be taken with the lasso, but when thus captured, it fights desperately, and no amount of attention or kindness can reconcile it to the loss of liberty.

Throughout South America it is one of the most abundant species, its geographical range extending even to Cape Horn. Mr. Darwin found the Polyborus nowhere so common as on the grassy savannas of the La Plata, and says that it is also found on the most desert plains of Patagonia, even to the rocky and barren shores of the Pacific.

Genus PANDION, Savigny

Pandion, Savign. 1809. (Type, Falco Haliætus, Linn.)

Triorchis, Leach, 1816. (Same type.)

Balbusardus, Fleming, 1828. (Same type.)

Gen. Char. Bill inflated, the cere depressed below the arched culmen; end of bill much developed, forming a strong, pendent hook. Anterior edge of nostril touching edge of the cere. Whole of tarsus and toes (except terminal joint) covered with rough, somewhat imbricated, projecting scales. Outer toe versatile; all the claws of equal length. In their shape, also, they are peculiar; they contract in thickness to their lower side, where they are much narrower than on top, as well as perfectly smooth and rounded; the middle claw has the usual sharp lateral ridge, but it is not very distinct. All the toes perfectly free. Tibiæ not plumed, but covered compactly with short feathers, these reaching down the front of the tarsus below the knee, and terminating in an angle. Primary coverts hard, stiff, and acuminate, almost as much so as the quills themselves; third quill longest; first longer than fifth; second, third, and fourth sinuated on outer webs; outer three deeply emarginated, the fourth sinuated, on inner webs.

Of this remarkable genus, there appears to be but a single species, which is almost completely cosmopolitan in its habitat. As in the case of the Peregrine Falcon and Barn Owl, different geographical regions have each a peculiar race, modified by some climatic or local influence. These races, however, are not well marked, and are consequently only definable with great difficulty.

Species and RacesP. haliætus. Wing, 15.20–21.50; tail, 7.00–11.11; culmen, 1.20–1.40; tarsus, 2.00–2.15; middle toe, 1.60–2.00. Second or third quills longest. Above clear dark grayish-brown, inclining to brownish-black, plain, or variegated with white. Tail brownish-gray (the inner webs almost entirely white), narrowly tipped with white, and crossed by about six or seven nearly equal bands of dusky-black. Head, neck, and entire lower parts, snowy-white; the breast with or without brown spots or wash. A dusky stripe on side of head (from lores across the ear-coverts), and top of head more or less spotted, or streaked, with the same. Adult. Upper parts plain. Young. Feathers of the upper parts bordered terminally with white. Sexes alike (?).

Wing, 17.00–20.50; tail, 7.00–10.00; culmen, 1.20–1.45; tarsus, 1.95–3.15; middle toe, 1.50–1.90. Second or third quills longest (in eighteen specimens from Europe and Asia). First longer than fifth. Breast always (?) spotted with brownish, or uniformly so; top of head with the black streaks usually predominating. Tail with six to seven narrow black bands, continuous across both webs. Hab. Northern Hemisphere of the Old World … var. haliætus.68

Wing, 17.50–21.50; tail, 8.70–10.50; culmen, 1.25–1.40; tarsus, 2.00–2.40; middle toe, 1.70–2.00. Second and third quill longest. Breast often entirely without spots; top of head and nape usually with dark streaks predominating. Tail with six to seven narrow black bands, continuous across both webs. Hab. Northern Hemisphere of the New World … var. “carolinensis.”

Wing, 17.50–19.50; tail, 9.00–10.00; culmen, 1.25–1.40; tarsus, 2.10; middle toe, 1.70–1.95. Third quill longest, but second just perceptibly shorter (eight specimens, including Gould’s types). Breast with the markings sometimes (in two out of the eight examples) reduced to sparse shaft-streaks, but never (?) entirely immaculate. Top of the head with the white streaks usually predominating, sometimes (in three out of the eight specimens) immaculate white (the occiput, however, always with a few streaks). Tail with six to seven white bands on the inner webs, which (according to Kaup) do not touch the shaft. Hab. Australia … var. “leucocephalus.”69

Pandion haliætus, var. carolinensis (Gmel.)FISH-HAWK; AMERICAN OSPREYFalco carolinensis, Gmel. Syst. Nat. p. 263, 1789.—Daud. Tr. Orn. II, 69, 1800. Pandion carolinensis, Bonap. List, pt. iii, 1838; Consp. Av. p. 16.—Strickl. Orn. Syn. I, 64, 1855.—Aud. Birds Am. pl. lxxxi, 1831.—Cass. Birds Cal. & Tex. p. 112, 1854.—Brewer, Oölogy, 1857, p. 53, pl. iii, fig. 33, 34.—Newb. P. R. R. Rept. VI, iv, 75, 1857.—Heerm. VII, 21, 1857.—De Kay, Zoöl. N. Y. II, 8, pl. vi, fig. 18.—Cass. Birds N. Am. 1858, p. 44.—Coop. & Suck. P. R. R. Rept. XII, ii, 153, 1860.—Coues, Prod. Orn. Ariz. 1866, p. 13.—Gray, Hand List, I, 15, 1869.—Max. Cab. Journ. VI, 1858, 11.—Lord, Pr. R. A. I. IV, 1864, 110 (Brit. Columb.; nesting).—Fowler, Am. Nat. II, 1868, 192 (habits). Falco cayennensis, Gmel. Syst. Nat. p. 263, 1789.—Daud. Tr. Orn. II, p. 69, 1800. Falco americanus, Gmel. Syst. Nat. p. 257.—Lath. Index Orn. p. 13, 1790; Syn. I, 35, 1781; Gen. Hist. I, 238, 1821.—Daud. Tr. Orn. II, 50.—Shaw, Zoöl. VII, 88. Aquila americana, Vieill. Ois. Am. Sept. I, pl. iv, 1807. Pandion americanus, Vieill. Gal. Ois. pl. ii, 1825.—Vig. Zoöl. Journ. I, 336.—Swains. Classif. B. II, 207, 1837. Aquila piscatrix, Vieill. Ois. Am. Sept. I, pl. iv, 1807. Accipiter piscatorius, Catesby, Carolina, I, pl. ii, 1754. A. falco piscator antillarum, Briss. Orn. I, 361, 1760. A. falco piscator carolinensis, Briss. Orn. I, 362. Pandion haliætus, Rich. Faun. Bor. Am. II, 20, 1831.—Jard. (Wils.) Am. Orn. II, 103, 1832.—James. (Wils.) Am. Orn. I, 38, 1831.—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 415, 1831.—Gray, List B. Brit. Mus. p. 22, 1844. ? Pandion fasciatus, Brehm, Allgem. deutsch. Zeitung, II, 1856, 66 (St. Domingo).