полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

72. Methods of greeting and observances between relatives

When two Gond friends or relatives meet, they clasp each other in their arms and lean against each shoulder in turn. A man will then touch the knees of an elder male relative with his fingers, carrying them afterwards to his own forehead. This is equivalent to falling at the other’s feet, and is a token of respect shown to all elder male relatives and also to a son-in-law, sister’s husband, and a samhdi, that is the father of a son- or daughter-in-law. Their term of salutation is Johār, and they say this to each other. Another method of greeting is that each should put his fingers under the other’s chin and then kiss them himself. Women also do this when they meet. Or a younger woman meeting an elder will touch her feet, and the elder will then kiss her on the forehead and on each cheek. If they have not met for some time they will weep. It is said that Baigas will kiss each other on the cheek when meeting, both men and women. A Gond will kiss and caress his wife after marriage, but as soon as she has a child he drops the habit and never does it again. When husband and wife meet after an absence the wife touches her husband’s feet with her hand and carries it to her forehead, but the husband makes no demonstration. The Gonds kiss their children. Among the Māria Gonds the wife is said not to sleep on a cot in her husband’s house, which would be thought disrespectful to him, but on the ground. Nor will a woman even sit on a cot in her own house, as if any male relative happened to be in the house it would be disrespectful to him. A woman will not say the name of her husband, his elder or younger brother, or his elder brother’s sons. A man will not mention his wife’s name nor that of her elder sister.

73. The caste panchāyat and social offences

The tribe have panchāyats or committees for the settlement of tribal disputes and offences. A member of the panchāyat is selected by general consent, and holds office during good behaviour. The office is not hereditary, and generally there does not seem to be a recognised head of the panchāyat. In Mandla there is a separate panchāyat for each village, and every Gond male adult belongs to it, and all have to be summoned to a meeting. When they assemble five leading elderly men decide the matter in dispute, as representing the assembly. Caste offences are of the usual Hindu type with some variations. Adultery, taking another man’s wife or daughter, getting vermin in a wound, being sent to jail and eating the jail food, or even having handcuffs put on, a woman getting her ear torn, and eating or even smoking with a man of very low caste, are the ordinary offences. Others are being beaten by a shoe, dealing in the hides of cattle or keeping donkeys, removing the corpse of a dead horse or donkey, being touched by a sweeper, cooking in the earthen pots of any impure caste, a woman entering the kitchen during her monthly impurity, and taking to wife the widow of a younger brother, but not of course of an elder brother.

In the case of septs which revere a totem animal or plant, any act committed in connection with that animal or plant by a member of the sept is an offence within the cognisance of the panchāyat. Thus in Mandla the Kumhra sept revere the goat and the Markām sept the crocodile and crab. If a member of one of these septs touches, keeps, kills or eats the animal which his sept reveres, he is put out of caste and comes before the panchāyat. In practice the offences with which the panchāyat most frequently deals are the taking of another man’s wife or the kidnapping of a daughter for marriage, this last usually occurring between relatives. Both these offences can also be brought before the regular courts, but it is usually only when the aggrieved person cannot get satisfaction from the panchāyat, or when the offender refuses to abide by its decision, that the case goes to court. If a Gond loses his wife he will in the ordinary course compromise the matter if the man who takes her will repay his wedding expenses; this is a very serious business for him, as his wedding is the principal expense of a man’s life, and it is probable that he may not be able to afford to buy another girl and pay for her wedding. If he cannot get his wedding expenses back through the panchāyat he files a complaint of adultery under the Penal Code, in the hope of being repaid through a fine inflicted on the offender, and it is perfectly right and just that this should be done. When a girl is kidnapped for marriage, her family can usually be induced to recognise the affair if they receive the price they could have got for the girl in an ordinary marriage, and perhaps a little more, as a solace to their outraged feelings.

The panchāyat takes no cognisance of theft, cheating, forgery, perjury, causing hurt and other forms of crime. These are not considered to be offences against the caste, and no penalty is inflicted for them. Only if a man is arrested and handcuffed, or if he is sent to jail for any such crime, he is put out of caste for eating the jail food and subjected in this latter case to a somewhat severe penalty. It is not clear whether a Gond is put out of caste for murder, though Hindu panchāyats take cognisance of this offence.

74. Caste penalty feasts

The punishments inflicted by the panchāyat consist of feasts, and in the case of minor offences of a fine. This last, subject perhaps to some commission to the members for their services, is always spent on liquor, the drinking of which by the offender with the caste-fellows will purify him. The Gonds consider country liquor as equivalent to the Hindu Amrita or nectar.

The penalty for a serious offence involves three feasts. The first, known as the meal of impurity, consists of sweet wheaten cakes which are eaten by the elders on the bank of a stream or well. The second or main feast is given in the offender’s courtyard to all the castemen of the village and sometimes of other villages. Rice, pulse, and meat, either of a slaughtered pig or goat, are provided at this. The third feast is known as ‘The taking back into caste’ and is held in the offender’s house and may be cooked by him. Wheat, rice and pulses are served, but not meat or vegetables. When the panchāyat have eaten this food in the offender’s house he is again a proper member of the caste. Liquor is essential at each feast. The nature of the penalty feasts is thus very clear. They have the effect of a gradual purification of the offender. In the first meal he can take no part, nor is it served in his house, but in some neutral place. For the second meal the castemen go so far as to sit in his compound, but apparently he does not cook the food nor partake of it. At the third meal they eat with him in his house and he is fully purified. These three meals are prescribed only for serious offences, and for ordinary ones only two meals, the offender partaking of the second. The three meals are usually exacted from a woman taken in adultery with an outsider. In this case the woman’s head is shaved at the first meal by the Sharmia, that is her son-in-law, and the children put her to shame by throwing lumps of cowdung at her. She runs away and bathes in a stream. At the second meal, taken in her courtyard, the Sharmia sprinkles some blood on the ground and on the lintel of the door as an offering to the gods and in order that the house may be pure for the future. If a man is poor and cannot afford the expense of the penalty feasts imposed on him, the panchāyat will agree that only a few persons will attend instead of the whole community. The procedure above described is probably borrowed to a large extent from Hinduism, but the working of a panchāyat can be observed better among the Gonds and lower castes than among high-caste Hindus, who are tending to let it lapse into abeyance.

75. Special purification ceremony

The following detailed process of purification had to be undergone by a well-to-do Gond widow in Mandla who had been detected with a man of the Panka caste, lying drunk and naked in a liquor-shop. The Gonds here consider the Pankas socially beneath themselves. The ritual clearly belongs to Hinduism, as shown by the purifying virtue attached to contact with cows and bullocks and cowdung, and was directed by the Panda or priest of Devi’s shrine, who, however, would probably be a Gond. First, the offending woman was taken right out of the village across a stream; here her head was shaved with the urine of an all-black bullock and her body washed with his dung, and she then bathed in the stream, and a feast was given on its bank to the caste. She slept here, and next day was yoked to the same bullock and taken thus to the Kharkha or standing-place for the village cattle. She was rolled over the surface of the Kharkha about four times, again rubbed with cowdung, another feast was given, and she slept the night on the spot, without being washed. Next day, covered with the dust and cowdung of the Kharkha, she crouched underneath the black bullock’s belly and in this manner proceeded to the gate of her own yard. Here a bottle of liquor and fifteen chickens were waved round her and afterwards offered at Devi’s shrine, where they became the property of the Panda who was conducting the ceremony. Another feast was given in her yard and the woman slept there. Next day the woman, after bathing, was placed standing with one foot outside her threshold and the other inside; a feast was given, called the feast of the threshold, and she again slept in her yard. On the following day came the final feast of purification in the house. The woman was bathed eleven times, and a hen, a chicken and five eggs were offered by the Panda to each of her household gods. Then she drank a little liquor from a cup of which the Panda had drunk, and ate some of the leavings of food of which he had eaten. The black bullock and a piece of cloth sufficient to cover it were presented to the Panda for his services. Then the woman took a dish of rice and pulse and placed a little in the leaf-cup of each of the caste-fellows present, and they all ate it and she was readmitted to caste. Twelve cow-buffaloes were sold to pay for the ceremony, which perhaps cost Rs. 600 or more.

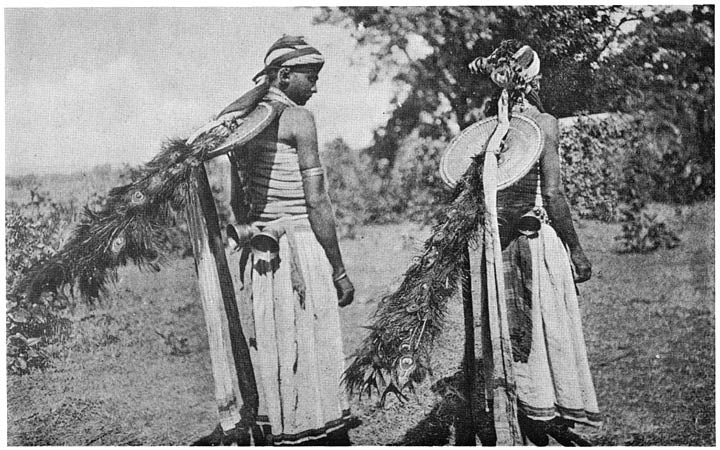

Māria Gonds in dancing costume

76. Dancing

Dancing and singing to the dance constitute the social amusement and recreation of the Gonds, and they are passionately fond of it. The principal dance is the Karma, danced in celebration of the bringing of the leafy branch of a tree from the forest in the rains. They continue to dance it as a recreation during the nights of the cold and hot weather, whenever they have leisure and a supply of liquor, which is almost indispensable, is forthcoming. The Mārias dance, men and women together, in a great circle, each man holding the girl next him on one side round the neck and on the other round the waist. They keep perfect time, moving each foot alternately in unison throughout the line, and moving round in a slow circle. Only unmarried girls may join in a Māria dance, and once a woman is married she can never dance again. This is no doubt a salutary provision for household happiness, as sometimes couples, excited by the dance and wine, run away from it into the jungle and stay there for a day or two till their relatives bring them home and consider them as married. At the Māria dances the men wear the skins of tigers, panthers, deer and other animals, and sometimes head-dresses of peacock’s feathers. They may also have a girdle of cowries round the waist, and a bell tied to their back to ring as they move. The musicians sit in the centre and play various kinds of drums and tom-toms. At a large Māria dance there may be as many as thirty musicians, and the provision of rice or kodon and liquor may cost as much as Rs. 50. In other localities the dance is less picturesque. Men and women form two long lines opposite each other, with the musicians in the centre, and advance and retreat alternately, bringing one foot forward and the other up behind it, with a similar movement in retiring. Married women may dance, and the men do not hold the women at any time. At intervals they break off and liquor is distributed in small leaf-cups, or if these are not available, it is poured into the hands of the dancers held together like a cup. In either case a considerable proportion of the liquor is usually spilt on to the ground.

77. Songs

All the time they are dancing they also sing in unison, the men sometimes singing one line and the women the next, or both together. The songs are with few exceptions of an erotic character, and a few specimens are subjoined.

a. Be not proud of your body, your body must go away above (to death).

Your mother, brother and all your kinsmen, you must leave them and go.

You may have lakhs of treasure in your house, but you must leave it all and go.

b. The musicians play and the feet beat on the earth.

A pice (¼d.) for a divorced woman, two pice for a kept woman, for a virgin many sounding rupees.

The musicians play and the earth sounds with the trampling of feet.

c. Rāja Darwa is dead, he died in his youth.

Who is he that has taken the small gun, who has taken the big bow?

Who is aiming through the harra and bahera trees, who is aiming on the plain?

Who has killed the quail and partridge, who has killed the peacock?

Rāja Darwa has died in the prime of his youth.

The big brother says, ‘I killed him, I killed him’; the little brother shot the arrow.

Rāja Darwa has died in the bloom of his youth.

d. Rāwan92 is coming disguised as a Bairāgi; by what road will Rāwan come?

The houses and castles fell before him, the ruler of Bhānwargarh rose up in fear.

He set the match to his powder, he stooped and crept along the ground and fired.

e. Little pleasure is got from a kept woman; she gives her lord pej (gruel) of kutki to drink.

She gives it him in a leaf-cup of laburnum;93 the cup is too small for him to drink.

She put two gourds full of water in it, and the gruel is so thin that it gives him no sustenance.

f. Man speaks:

The wife is asleep and her Rāja (husband) is asleep in her lap.

She has taken a piece of bread in her lap and water in her vessel.

See from her eyes will she come or not?

Woman:

I have left my cow in her shed, my buffalo in her stall.

I have left my baby at the breast and am come alone to follow you.

g. The father said to his son, ‘Do not go out to service with any master, neither go to any strange woman.

I will sell my sickle and axe, and make you two marriages.’

He made a marriage feast for his son, and in one plate he put rice, and over it meat, and poured soup over it till it flowed out of the plate.

Then he said to the men and women, young and old, ‘Come and eat your fill.’

78. Language

In 1911 Gondi was spoken by 1,500,000 persons, or more than half the total number of Gonds in India. The other Gonds of the Central Provinces speak a broken Hindi. Gondi is a Dravidian language, having a common ancestor with Tamil and Canarese, but little immediate connection with its neighbour Telugu; the specimens given by Sir G. Grierson show that a large number of Hindi words have been adopted into the vocabulary of Gondi, and this tendency is no doubt on the increase. There are probably few Gonds outside the Feudatory States, and possibly a few of the wildest tracts in British Districts, who could not understand Hindi to some extent. And with the extension of primary education in British Districts Gondi is likely to decline still more rapidly. Gondi has no literature and no character of its own; but the Gospels and the Book of Genesis have been translated into it and several grammatical sketches and vocabularies compiled. In Saugor the Hindus speak of Gondi as Farsi or Persian, apparently applying this latter name to any foreign language.

(h) Occupation

79. Cultivation

The Gonds are mainly engaged in agriculture, and the great bulk of them are farmservants and labourers. In the hilly tracts, however, there is a substantial Gond tenantry, and a small number of proprietors remain, though the majority have been ousted by Hindu moneylenders and liquor-sellers. In the eastern Districts many important zamīndāri estates are owned by Gond proprietors. The ancestors of these families held the wild hilly country on the borders of the plains in feudal tenure from the central rulers, and were responsible for the restraint of the savage hillmen under their jurisdiction, and the protection of the rich and settled lowlands from predatory inroads from without. Their descendants are ordinary landed proprietors, and would by this time have lost their estates but for the protection of the law declaring them impartible and inalienable. A few of the Feudatory Chiefs are also Gonds. Gond proprietors are generally easy-going and kind-hearted to their tenants, but lacking in business acumen and energy, and often addicted to drink and women. The tenants are as a class shiftless and improvident and heavily indebted. But they show signs of improvement, especially in the ryotwāri villages under direct Government management, and it may be hoped that primary education and more temperate habits will gradually render them equal to the Hindu cultivators.

80. Patch cultivation

In the Feudatory States and some of the zamīndāris the Gonds retain the dahia or bewar method of shifting cultivation, which has been prohibited everywhere else on account of its destructive effects on the forests. The Māria Gonds of Bastar cut down a patch of jungle on a hillside about February, and on its drying up burn all the wood in April or May. Tying strips of the bark of the sāj tree to their feet to prevent them from being burnt, they walk over the smouldering area, and with long bamboo sticks move any unburnt logs into a burning patch, so that they may all be consumed. When the first showers of rain fall they scatter seed of the small millets into the soft covering of wood ashes, and the fertility of the soil is such that without further trouble they get a return of a hundred-fold or more. The same patch can be sown for three years in succession without ploughing, but it then gives out, and the Gonds move themselves and their habitations to a fresh one. When the jungle has been allowed to grow on the old patch for ten or twelve years, there is sufficient material for a fresh supply of wood-ash manure, and they burn it over again. Teak yields a particularly fertilising ash, and when standing the tree is hurtful to crops grown near it, as its large, broad leaves cause a heavy drip and wash out the grain. Hence the Gonds were particularly hostile to this tree, and it is probably to their destructive efforts that the poor growth of teak over large areas of the Provincial forests is due.94 The Māria Gonds do not use the plough, and their only agricultural implement is a kind of hoe or spade. Elsewhere the Gonds are gradually adopting the Hindu methods of cultivation, but their land is generally in hilly and jungly tracts and of poor quality. They occupy large areas of the wretched barra or gravel soil which has disintegrated from the rock of the hillsides, and covers it in a thin sheet mixed with quantities of large stones. The Gonds, however, like this land, as it is so shallow as to entail very little trouble in ploughing, and it is suitable for their favourite crops of the small millets, kodon and kutki, and the poorer oilseeds. After three years of cropping it must be given an equal or longer period of fallow before it will again yield any return. The Gonds say it is nārang or exhausted. In the new ryotwāri villages formed within the last twenty years the Gonds form a large section, and in Mandla the great majority, of the tenantry, and have good black-soil fields which grow wheat and other valuable crops. Here, perhaps, their condition is happier than anywhere else, as they are secured in the possession of their lands subject to the payment of revenue, liberally assisted with Government loans at low interest, and protected as far as possible from the petty extortion and peculation of Hindu subordinate officials and moneylenders. The opening of a substantial number of primary schools to serve these villages will, it may be hoped, have the effect of making the Gond a more intelligent and provident cultivator, and counteract the excessive addiction to liquor which is the great drawback to his prosperity. The fondness of the Gond for his bāri or garden plot adjoining his hut has been described in the section on villages and houses.

81. Hunting: traps for animals

The primary occupation of the Gonds in former times was hunting and fishing, but their opportunities in this respect have been greatly circumscribed by the conservation of the game in Government forests, which was essential if it was not to become extinct, when the native shikāris had obtained firearms. Their weapons were until recently bows and arrows, but now Gond hunters usually have an old matchlock gun. They have several ingenious devices for trapping animals. It is essential for them to make a stockade round their patch cultivation fields in the forests, or the grain would be devoured by pig and deer. At one point in this they leave a narrow opening, and in front of it dig a deep pit and cover it with brushwood and grass; then at the main entrance they spread some sand. Coming in the middle of the night they see from the footprints in the sand what animals have entered the enclosure; if these are worth catching they close the main gate, and make as much noise as they can. The frightened animals dash round the enclosure and, seeing the opening, run through it and fall into the pit, where they are easily despatched with clubs and axes. They also set traps across the forest paths frequented by animals. The method is to take a strong raw-hide rope and secure one end of it to a stout sapling, which is bent down like a spring. The other end is made into a noose and laid open on the ground, often over a small hole. It is secured by a stone or log of wood, and this is so arranged by means of some kind of fall-trap that on pressure in the centre of the hole it is displaced and releases the noose. The animal comes and puts his foot in the hole, thus removing the trap which secured the noose. This flies up and takes the animal’s foot with it, being drawn tight in mid-air by the rebound of the sapling. The animal is thus suspended with one foot in the air, which it cannot free, and the Gonds come and kill it. Tigers are sometimes caught in this manner. A third very cruel kind of trap is made by putting up a hedge of thorns and grass across a forest-path, on the farther side of which they plant a few strong and sharply-pointed bamboo stakes. A deer coming up will jump the hedge, and on landing will be impaled on one of the stakes. The wound is very severe and often festers immediately, so that the victim dies in a few hours. Or they suspend a heavy beam over a forest path held erect by a loose prop which stands on the path. The deer comes along and knocks aside the prop, and the beam falls on him and pins him down. Mr. Montgomerie writes as follows on Gond methods of hunting:95 “The use of the bow and arrow is being forgotten owing to the restrictions placed by Government on hunting. The Gonds can still throw an axe fairly straight, but a running hare is a difficult mark and has a good chance of escaping. The hare, however, falls a victim to the fascination of fire. The Gond takes an earthen pot, knocks a large hole in the side of it, and slings it on a pole with a counterbalancing stone at the other end. Then at night he slings the pole over one shoulder, with the earthen pot in front containing fire, and sallies out hare-hunting. He is accompanied by a man who bears a bamboo. The hare, attracted and fascinated by the light, comes close and watches it stupidly till the bamboo descends on the animal’s head, and the Gonds have hare for supper.” Sometimes a bell is rung as well, and this is said to attract the animals. They also catch fish by holding a lamp over the water on a dark night and spearing them with a trident.