полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

50. Witchcraft

The belief in witchcraft has been till recently in full force and vigour among the Gonds, and is only now showing symptoms of decline. In 1871 Sir C. Grant wrote:75 “The wild hill country from Mandla to the eastern coast is believed to be so infested by witches that at one time no prudent father would let his daughter marry into a family which did not include among its members at least one of the dangerous sisterhood. The non-Aryan belief in the power of evil here strikes a ready chord in the minds of their conquerors, attuned to dread by the inhospitable appearance of the country and the terrible effect of its malicious influences upon human life. In the wilds of Mandla there are many deep hillside caves which not even the most intrepid Baiga hunter would approach for fear of attracting upon himself the wrath of their demoniac inhabitants; and where these hillmen, who are regarded both by themselves and by others as ministers between men and spirits, are afraid, the sleek cultivator of the plains must feel absolute repulsion. Then the suddenness of the epidemics to which, whether from deficient water-supply or other causes, Central India seems so subject, is another fruitful source of terror among an ignorant people. When cholera breaks out in a wild part of the country it creates a perfect stampede—villages, roads, and all works in progress are deserted; even the sick are abandoned by their nearest relations to die, and crowds fly to the jungles, there to starve on fruits and berries till the panic has passed off. The only consideration for which their minds have room at such times is the punishment of the offenders, for the ravages caused by the disease are unhesitatingly set down to human malice. The police records of the Central Provinces unfortunately contain too many sad instances of life thus sacrificed to a mad unreasoning terror.” The detection of a witch by the agency of the corpse, when the death is believed to have been caused by witchcraft, has been described in the section on funeral rites. In other cases a lamp was lighted and the names of the suspected persons repeated; the flicker of the lamp at any name was held to indicate the witch. Two leaves were thrown on the outstretched hand of a suspected person, and if the leaf representing her or him fell above the other suspicion was deepened. In Bastar the leaf ordeal was followed by sewing the person accused into a sack and letting her down into shallow water; if she managed in her struggles for life to raise her head above water she was finally adjudged to be guilty. A witch was beaten with rods of the tamarind or castor-oil plants, which were supposed to be of peculiar efficacy in such cases; her head was shaved cross-wise from one ear to the other over the head and down to the neck; her teeth were sometimes knocked out, perhaps to prevent her from doing mischief if she should assume the form of a tiger or other wild animal; she was usually obliged to leave the village, and often murdered. Murder for witchcraft is now comparatively rare as it is too often followed by detection and proper punishment. But the belief in the causation of epidemic disease by personal agency is only slowly declining. Such measures as the disinfection of wells by permanganate of potash during a visitation of cholera, or inoculation against plague, are sometimes considered as attempts on the part of the Government to reduce the population. When the first epidemic of plague broke out in Mandla in 1911 it caused a panic among the Gonds, who threatened to attack with their axes any Government officer who should come to their village, in the belief that all of them must be plague-inoculators. In the course of six months, however, the feeling of panic died down under a system of instruction by schoolmasters and other local officials and by circulars; and by the end of the period the Gonds began to offer themselves voluntarily for inoculation, and would probably have come to do so in fairly large numbers if the epidemic had not subsided.

51. Human sacrifice.76

The Gonds were formerly accustomed to offer human sacrifices, especially to the goddess Kāli and to the goddess Danteshwari, the tutelary deity of the Rājas of Bastar. Her shrine was at a place called Dantewāra, and she was probably at first a local goddess and afterwards identified with the Hindu goddess Kāli. An inscription recently found in Bastar records the grant of a village to a Medipota in order to secure the welfare of the people and their cattle. This man was the head of a community whose business it was, in return for the grants of land which they enjoyed, to supply victims for human sacrifice either from their own families or elsewhere. Tradition states that on one occasion as many as 101 persons were sacrificed to avert some great calamity which had befallen the country. And sacrifices also took place when the Rāja visited the temple. During the period of the Bhonsla rule early in the nineteenth century the Rāja of Bastar was said to have immolated twenty-five men before he set out to visit the Rāja of Nāgpur at his capital. This would no doubt be as an offering for his safety, and the lives of the victims were given as a substitute for his own. A guard was afterwards placed on the temple by the Marāthas, but reports show that human sacrifice was not finally stamped out until the Nāgpur territories lapsed to the British in 1853. At Chānda and Lānji also, Mr. Hislop states, human sacrifices were offered until well into the nineteenth century77 at the temples of Kāli. The victim was taken to the temple after sunset and shut up within its dismal walls. In the morning, when the door was opened, he was found dead, much to the glory of the great goddess, who had shown her power by coming during the night and sucking his blood. No doubt there must have been some of her servants hid in the fane whose business it was to prepare the horrid banquet. It is said that an iron plate was afterwards put over the face of the goddess to prevent her from eating up the persons going before her. In Chānda the legend tells that the families of the town had each in turn to supply a victim to the goddess. One day a mother was weeping bitterly because her only son was to be taken as the victim, when an Ahīr passed by, and on learning the cause of her sorrow offered to go instead. He took with him the rope of hair with which the Ahīrs tie the legs of their cows when milking them and made a noose out of it. When the goddess came up to him he threw the noose over her neck and drew it tight like a Thug. The goddess begged him to let her go, and he agreed to do so on condition that she asked for no more human victims. No doubt, if the legend has any foundation, the Ahīr found a human neck within his noose. It has been suggested in the article on Thug that the goddess Kāli is really the deified tiger, and if this were so her craving for human sacrifices is readily understood. All the three places mentioned, Dantewāra, Lānji and Chānda, are in a territory where tigers are still numerous, and certain points in the above legends favour the idea of this animal origin of the goddess. Such are the shutting of the victim in the temple at night as an animal is tied up for a tiger-kill, and the closing of her mouth with an iron plate as the mouths of tigers are sometimes supposed to be closed by magic. Similarly it may perhaps be believed that the Rāja of Bastar offered human sacrifices to protect himself and his party from the attacks of tigers, which would be the principal danger on a journey to Nāgpur. In Mandla there is a tradition that a Brāhman boy was formerly sacrificed at intervals to the god Bura Deo, and the forehead of the god was marked with his hair in place of sandalwood, and the god bathed in his blood and used his bones as sticks for playing at ball. Similarly in Bindrānawāgarh in Raipur the Gonds are said to have entrapped strangers and offered them to their gods, and if possible a Brāhman was obtained as the most suitable offering. These legends indicate the traditional hostility of the Gonds to the Hindus, and especially to the Brāhmans, by whom they were at one time much oppressed and ousted from their lands. According to tradition, a Gond Rāja of Garha-Mandla, Madhkur Shāh, had treacherously put his elder brother to death. Divine vengeance overtook him and he became afflicted with chronic pains in the head. No treatment was of avail, and he was finally advised that the only means of appeasing a justly incensed deity was to offer his own life. He determined to be burnt inside the trunk of the sacred pīpal tree, and a hollow trunk sufficiently dry for the purpose having been found at Deogarh, twelve miles from Mandla, he shut himself up in it and was burnt to death. The story is interesting as showing how the neurotic or other pains, which are the result of remorse for a crime, are ascribed to the vengeance of a divine providence.

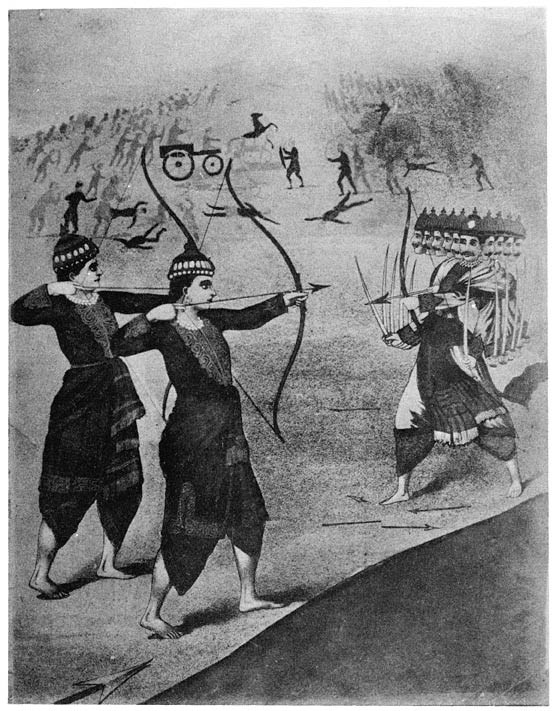

Killing of Rāwan, the demon king of Ceylon, from whom the Gonds are supposed to be descended

52. Cannibalism

Mr. Wilson quotes78 an account, written by Lieutenant Prendergast in 1820, in which he states that he had discovered a tribe of Gonds who were cannibals, but ate only their own relations. The account was as follows: “In May 1820 I visited the hills of Amarkantak, and having heard that a particular tribe of Gonds who lived in the hills were cannibals, I made the most particular inquiries assisted by my clerk Mohan Singh, an intelligent and well-informed Kāyasth. We learned after much trouble that there was a tribe of Gonds who resided in the hills of Amarkantak and to the south-east in the Gondwāna country, who held very little intercourse with the villagers and never went among them except to barter or purchase provisions. This race live in detached parties and seldom have more than eight or ten huts in one place. They are cannibals in the real sense of the word, but never eat the flesh of any person not belonging to their own family or tribe; nor do they do this except on particular occasions. It is the custom of this singular people to cut the throat of any person of their family who is attacked by severe illness and who they think has no chance of recovering, when they collect the whole of their relations and friends, and feast upon the body. In like manner when a person arrives at a great age and becomes feeble and weak, the Halālkhor operates upon him, when the different members of the family assemble for the same purpose as above stated. In other respects this is a simple race of people, nor do they consider cutting the throats of their sick relations or aged parents any sin; but on the contrary an act acceptable to Kāli, a blessing to their relatives, and a mercy to their whole race.”

It may be noted that the account is based on hearsay only, and such stories are often circulated about savage races. But if correct, it would indicate probably only a ritual form of cannibalism. The idea of the Gonds in eating the bodies of their relatives would be to assimilate the lives of these as it were, and cause them to be reborn as children in their own families. Possibly they ate the bodies of their parents, as many races ate the bodies of animal gods, in order to obtain their divine virtues and qualities. No corroboration of this custom is known in respect of the Gonds, but Colonel Dalton records79 a somewhat similar story of the small Birhor tribe who live in the Chota Nāgpur hills not far from Amarkantak, and it has been seen that the Bhunjias of Bilāspur eat small portions of the bodies of their dead relatives.80

53. Festivals. The new crops

The original Gond festivals were associated with the first eating of the new crops and fruits. In Chait (March) a festival called Chaitrai is observed in Bastar. A pig or fowl with some liquor is offered to the village god, and the new urad and semi beans of the year’s crop are placed before him uncooked. The people dance and sing the whole night and begin eating the new pulse and beans. In Bhādon (August) is the Nawākhai or eating of the new rice. The old and new grain is mixed and offered raw to the ancestors, a goat is sacrificed, and they begin to eat the new crop of rice. Similarly when the mahua flowers, from which country spirit is made, first appear, they proceed to the forest and worship under a sāj tree.

Before sowing rice or millet they have a rite called Bījphūtni or breaking the seed. Some grain, fowls and a pig are collected from the villagers by subscription. The grain is offered to the god and then distributed to all the villagers, who sow it in their fields for luck.

54. The Holi festival

The Holi festival, which corresponds to the Carnival, being held in spring at the end of the Hindu year, is observed by Gonds as well as Hindus. In Bilāspur a Gond or Baiga, as representing the oldest residents, is always employed to light the Holi fire. Sometimes it is kindled in the ancient manner by the friction of two pieces of wood. In Mandla, at the Holi, the Gonds fetch a green branch of the semar or cotton tree and plant it in a little hole, in which they put also a pice (farthing) and an egg. They place fuel round and burn up the branch. Then next day they take out the egg and give it to a dog to eat and say that this will make the dog as swift as fire. They choose a dog whom they wish to train for hunting. They bring the ploughshare from the house and heat it red-hot in the Holi fire and take it back. They say that this wakes up the ploughshare, which has fallen asleep from rusting in the house, and makes it sharp for ploughing. Perhaps when rust appears on the metal they think this a sign of its being asleep. They plough for the first time on a Monday or Wednesday and drive three furrows when nobody is looking.

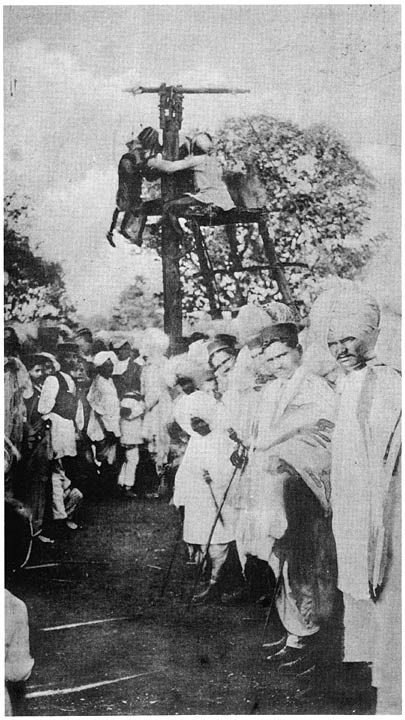

Woman about to be swung round the post called Meghnāth

55. The Meghnāth swinging rite

In the western Districts on one of the five days following the Holi the swinging rite is performed. For this they bring a straight teak or sāj tree from the forest, as long as can be obtained, and cut from a place where two trees are growing together. The Bhumka or village priest is shown in a dream where to cut the tree. It is set up in a hole seven feet deep, a quantity of salt being placed beneath it. The hole is coloured with geru or red ochre, and offerings of goats, sheep and chickens are made to it by people who have vowed them in sickness. A cross-bar is fixed on to the top of the pole in a socket and the Bhumka is tied to one end of the cross-bar. A rope is attached to the other end and the people take hold of this and drag the Bhumka round in the air five times. When this has been done the village proprietor gives him a present of a cocoanut, and head- and body-clothes. If the pole falls down it is considered that some great misfortune, such as an epidemic, will ensue. The pole and ritual are now called Meghnāth. Meghnāth is held to have been the son of Rāwan, the demon king of Ceylon, from whom the Gonds are supposed by the Hindus to be descended, as they are called Rāwanvansi, or of the race of Rāwan. After this they set up another pole, which is known as Jheri, and make it slippery with oil, butter and other things. A little bag containing Rs. 1–4 and also a seer (2 lbs.) of ghī or butter are tied to the top, and the men try to climb the pole and get these as a prize. The women assemble and beat the men with sticks as they are climbing to prevent them from doing so. If no man succeeds in climbing the pole and getting the reward, it is given to the women. This seems to be a parody of the first or Meghnāth rite, and both probably have some connection with the growth of the crops.

56. The Karma and other rites

During Bhādon (August), in the rains, the Gonds bring a branch of the kalmi or of the haldu tree from the forest and wrap it up in new cloth and keep it in their houses. They have a feast and the musicians play, and men and women dance round the branch singing songs, of which the theme is often sexual. The dance is called Karma and is the principal dance of the Gonds, and they repeat it at intervals all through the cold weather, considering it as their great amusement. A further notice of it is given in the section on social customs. The dance is apparently named after the tree, though it is not known whether the same tree is always selected. Many deciduous trees in India shed their leaves in the hot weather and renew them in the rains, so that this season is partly one of the renewal of vegetation as well as of the growth of crops.

Climbing the pole for a bag of sugar

In Kunwār (September) the Gond girls take an earthen pot, pierce it with holes, and put a lamp inside and also the image of a dove, and go round from house to house singing and dancing, led by a girl carrying the pot on her head. They collect contributions and have a feast. In Chhattīsgarh among the Gonds and Rāwats (Ahīrs) there is from time to time a kind of feminist movement, which is called the Stiria-Rāj or kingdom of women. The women pretend to be soldiers, seize all the weapons, axes and spears that they can get hold of, and march in a body from village to village. At each village they kill a goat and send its head to another village, and then the women of that village come and join them. During this time they leave their hair unbound and think that they are establishing the kingdom of women. After some months the movement subsides, and it is said to occur at irregular intervals with a number of years between each. The women are commonly considered to be out of their senses.

(g) Appearance and Character, and Social Rules and Customs

57. Physical type

Hislop describes the Gonds as follows:81 “All are a little below the average size of Europeans and in complexion darker than the generality of Hindus. Their bodies are well proportioned, but their features rather ugly. They have a roundish head, distended nostrils, wide mouth, thickish lips, straight black hair and scanty beard and moustache. It has been supposed that some of the aborigines of Central India have woolly hair; but this is a mistake. Among the thousands I have seen I have not found one with hair like a negro.” Captain Forsyth says:82 “The Gond women differ among themselves more than the men. They are somewhat lighter in colour and less fleshy than Korku women. But the Gond women of different parts of the country vary greatly in appearance, many of them in the open tracts being great robust creatures, finer animals by far than the men; and here Hindu blood may fairly be expected. In the interior again bevies of Gond women may be seen who are more like monkeys than human beings. The features of all are strongly marked and coarse. The girls occasionally possess such comeliness as attaches to general plumpness and a good-humoured expression of face; but when their short youth is over all pass at once into a hideous age. Their hard lives, sharing as they do all the labours of the men except that of hunting, suffice to account for this.” There is not the least doubt that the Gonds of the more open and civilised country, comprised in British Districts, have a large admixture of Hindu blood. They commonly work as farmservants, women as well as men, and illicit connections with their Hindu masters have been a natural result. This interbreeding, as well as the better quality of food which those who have taken to regular cultivation obtain, have perhaps conduced to improve the Gond physical type. Gond men as tall as Hindus, and more strongly built and with comparatively well-cut features, are now frequently seen, though the broad flat nose is still characteristic of the tribe as a whole. Most Gonds have very little hair on the face.

58. Character

Of the Māria Gonds, Colonel Glasfurd wrote83 that “They are a timid, quiet race, docile, and though addicted to drinking they are not quarrelsome. Without exception they are the most cheerful, light-hearted people I have met with, always laughing and joking among themselves. Seldom does a Māria village resound with quarrels or wrangling among either sex, and in this respect they present a marked contrast to those in more civilised tracts. They, in common with many other wild races, bear a singular character for truthfulness and honesty, and when once they get over the feeling of shyness which is natural to them, are exceedingly frank and communicative.” Writing in 1825 Sleeman said: “Such is the simplicity and honesty of character of the wildest of these Gonds that when they have agreed to a jama84 they will pay it, though they sell their children to do so, and will also pay it at the precise time that they agreed to. They are dishonest only in direct theft, and few of them will refuse to take another man’s property when a fair occasion offers, but they will immediately acknowledge it.”85 The more civilised Gonds retain these characteristics to a large extent, though contact with the Hindus and the increased complexity of life have rendered them less guileless. Murder is a comparatively frequent crime among Gonds, and is usually due either to some quarrel about a woman or to a drunken affray. The kidnapping of girls for marriage is also common, though hardly reckoned as an offence by the Gonds themselves. Otherwise crime is extremely rare in Gond villages as a rule. As farmservants the Gonds are esteemed fairly honest and hard-working; but unless well driven they are constitutionally averse to labour, and care nothing about provision for the future. The proverb says, ‘The Gond considers himself a king as long as he has a pot of grain in the house,’ meaning that while he has food for a day or two he will not work for any more. During the hot weather the Gonds go about in parties and pay visits to their relatives, staying with them several days, and the time is spent simply in eating, drinking when liquor is available, and conversation. The visitors take presents of grain and pulse with them and these go to augment the host’s resources. The latter will kill a chicken or, as a great treat, a young pig. Mr. Montgomerie writes of the Gonds as follows:86 “They are a pleasant people, and leave kindly memories in those who have to do with them. Comparatively truthful, always ready for a laugh, familiar with the paths and animals and fruits of the forest, lazy cultivators on their own account but good farmservants under supervision, the broad-nosed Gonds are the fit inhabitants of the hilly and jungly tracts in which they are found. With a marigold tucked into his hair above his left ear, with an axe in his hand and a grin on his face, the Gond turns out cheerfully to beat for game, and at the end of the day spends his beating pay on liquor for himself or on sweetmeats for his children. He may, in the previous year, have been subsisting largely on jungle fruits and roots because his harvest failed, but he does not dream of investing his modest beating pay in grain.”

59. Shyness and ignorance

In the wilder tracts the Gonds were, until recently, extremely shy of strangers, and would fly at their approach. Their tribute to the Rāja of Bastar, paid in kind, was collected once a year by an officer who beat a tom-tom outside the village and forthwith hid himself, whereupon the inhabitants brought out whatever they had to give and deposited it on an appointed spot. Colonel Glasfurd notes that they had great fear of a horse, and the sight of a man on horseback would put a whole village to flight.87 Even within the writer’s experience, in the wilder forest tracts of Chānda Gond women picking up mahua would run and climb a tree at one’s approach on a pony. As displaying the ignorance of the Gonds, Mr. Cain relates88 that about forty years ago a Gond was sent with a basket of mangoes from Palvatsa to Bhadrachalam, and was warned not to eat any of the fruit, as it would be known if he did so from a note placed in the basket. On the way, however, the Gond and his companion were overcome by the attraction of the fruit, and decided that if they buried the note it would be unable to see them eating. They accordingly did so and ate some of the mangoes, and when taxed with their dishonesty at the journey’s end, could not understand how the note could have known of their eating the mangoes when it had not seen them.