полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

7. The Rāwanvansis

Another curious class of Gosains are the Rāwanvansis, who go about in the character of Rāwan, the demon king of Ceylon, as he was when he carried off Sīta. The legend is that in order to do this, Rāwan first sent his brother in the shape of a golden deer before Rāma’s palace. Sīta saw it and said she must have the head of the deer, and sent Rāma to kill it. So Rāma pursued it to the forest, and from there Rāwan cried out, imitating Rāma’s voice. Then Sīta thought Rāma was being attacked and told his brother Lachman to go to his help. But Lachman had been left in charge of her by Rāma and refused to leave her, till Sīta said he was hoping Rāma would be killed, so that he might marry her. Then he drew a circle round her on the ground, and telling her not to step outside it until his return, went off. Then Rāwan took the disguise of a beggar and came and begged for alms from Sīta. She told him to come inside the magic circle and she would give him alms, but he refused. So finally Sīta came outside the circle, and Rāwan at once seized her and carried her off to Ceylon. The Rāwanvansi Gosains wear rings of hair all up their arms and a rope of hair round the waist, and the hair of their head hanging down. It would appear that they are intended to represent some animal. They smear vermilion on the forehead, and beg only at twilight and never at any other time, whether they obtain food or not. In begging they will never move backwards, so that when they have passed a house they cannot take alms from it unless the householder brings the gift to them.

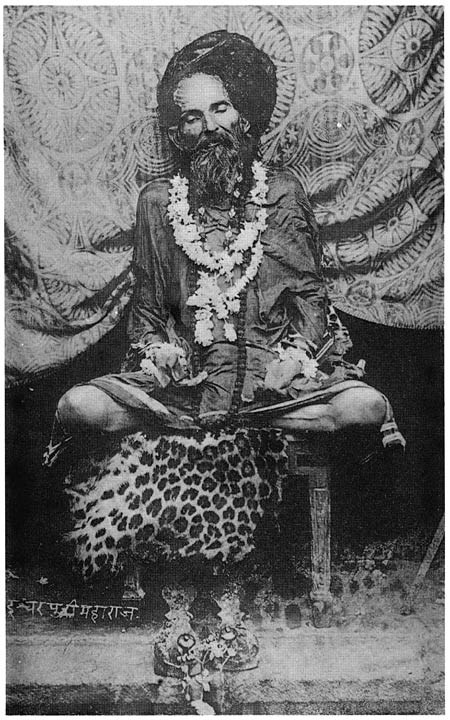

Famous Gosain Mahant. Photograph taken after death

8. Monasteries

Unmarried Sanniāsis often reside in Maths or monasteries. The superior is called Mahant, and he appoints his successor by will from the members. The Mahant admits all those willing and qualified to enter the order. If the applicant is young the consent of the parents is usually obtained; and parents frequently vow to give a child to the order. Many convents have considerable areas of land attached to them, and also dependent institutions. The whole property of the convent and its dependencies seems to be at the absolute disposal of the Mahant, but he is bound to give food, raiment and lodging to the inmates, and he entertains all travellers belonging to the order.109

9. The fighting Gosains

In former times the Gosains often became soldiers and entered the service of different military chiefs. The most famous of these fighting priests were the Nāga Gosains of the Jaipur State of Rājputāna, who are said to have been under an obligation from their guru or religious chief to fight for the Rāja of Jaipur whenever required. They received rent-free lands and pay of two pice (½d.) a day, which latter was put into a common treasury and expended on the purchase of arms and ammunition whenever needed for war. They would also lend money, and if a debtor could not pay would make him give his son to be enrolled in the force. The 7000 Nāga Gosains were placed in the vanguard of the Jaipur army in battle. Their weapons were the bow, arrow, shield, spear and discus. The Gosain proprietor of the Deopur estate in Raipur formerly kept up a force of Nāga Gosains, with which he used to collect the tribute from the feudatory chiefs of Chhattīsgarh on behalf of the Rāja of Nāgpur. It is said that he once invaded Bastar with this object, where most of the Gosains died of cholera. But after they had fasted for three days, the goddess Danteshwari appeared to them and promised them her protection. And they took the goddess away with them and installed her in their own village in Raipur. Forbes records that in Gujarāt an English officer was in command of a troop known as the Gosain’s wife’s troops. These Nāga Gosains wore only a single white garment, like a sleeveless shirt reaching to the knees, and hence it is said that they were called naked. The Gosains and Bairāgis, or adherents of Siva and Vishnu, were often engaged in religious quarrels on the merits of their respective deities, and sometimes came to blows. A favourite point of rivalry was the right of bathing first in the Ganges on the occasion of one of the great religious fairs at Allahābād or Hardwār. The Gosains claim priority of bathing, on the ground that the Ganges flows from the matted locks of Siva; while the Bairāgis assert that the source of the river is from Vishnu’s foot. In 1760 a pitched battle on this question ended in the defeat of the Bairāgis, of whom 1800 were slain. Again in 1796 the Gosains engaged in battle with the Sikh pilgrims and were defeated with the loss of 500 men.110 During the reign of Akbar a combat took place in the Emperor’s presence between the two Sivite sects of Gosains, or Sanniāsis and Jogis, having been apparently arranged for his edification, to decide which sect had the best ground for its pretensions to supernatural power. The Jogis were completely defeated.111

10. Burial

A dead Sanniāsi is always buried in the sitting attitude of religious contemplation with the legs crossed. The grave may be dug with a side receptacle for the corpse so that the earth, on being filled in, does not fall on it. The corpse is bathed and rubbed with ashes and clad in a new reddish-coloured shirt, with a rosary round the neck. The begging-wallet with some flour and pulse are placed in the grave, and also a gourd and staff. Salt is put round the body to preserve it, and an earthen pot is put over the head. Sometimes cocoanuts are broken on the skull, to crack it and give exit to the soul. Perhaps the idea of burial and of preserving the corpse with salt is that the body of an ascetic does not need to be purified by fire from the appetites and passions of the flesh like that of an ordinary Hindu; it is already cleansed of all earthly frailty by his austerities, and the belief may therefore have originally been that such a man would carry his body with him to the afterworld or to absorption with the deity. The burial of a Sanniāsi is often accompanied with music and signs of rejoicing; Mr. Oman describes such a funeral in which the corpse was seated in a litter, open on three sides so that it could be seen; it was tied to the back of the litter, and garlands of flowers partly covered the body, but could not conceal the hideousness of death as the unconscious head rolled helplessly from side to side with the movement of the litter. The procession was headed by a European brass band and by men carrying censers of incense.112

11. Sexual indulgence

Celibacy is the rule of the Gosain orders, and a man’s property passes in inheritance to a selected chela or disciple. But the practice of keeping women is very common, even outside the large section of the community which now recognises marriage. Women could be admitted into the order, when they had to shave their heads, assume the ochre-coloured shirt and rub their bodies with ashes. Afterwards, with the permission of the guru and on payment of a fine, they could let their hair grow again, at least temporarily. These women were supposed to remain quite chaste and live in nunneries, but many of them lived with men of the order. It is not known to what extent women are admitted at present. The sons born of such unions would be adopted as chelas or disciples by other Gosains, and made their heirs by a reciprocal arrangement. Women who are convicted of some social offence, or who wish to leave their husbands, often join the order nominally and live with a Gosain or are married into the caste. Many of the wandering mendicants lead an immoral life, and scandals about their enticing away the wives of rich Hindus are not infrequent.113 During their visits to villages they also engage in intrigues, and a ribald Gond song sung at the Holi festival describes the pleasure of the village women at the arrival of a Gosain owing to the sexual gratification which they expected to receive from him.

12. Missionary work

Nevertheless the wandering Gosains have done much to foster and maintain the Hindu religion among the people. They are the gurus or spiritual preceptors of the middle and lower castes, and though their teaching may be of little advantage, it perhaps quickens and maintains to some extent the religious feelings of their clients. In former times the Gosains travelled over the wildest tracts of country, proselytising the primitive non-Aryan tribes, for whose conversion to Hinduism they are largely responsible. On such journeys they necessarily carried their lives in their hands, and not infrequently lost them.

13. The Gosain caste

The majority of the Gosains are, however, now married and form an ordinary caste. Buchanan states that the ten different orders became exogamous groups, the members of which married with each other, but it is doubtful whether this is the case at present. It is said that all Giri Gosains marry, whether they are mendicants or not, while the Bhārthi order can marry or not as they please. They prohibit any marriage between first cousins, but permit widow remarriage and divorce. They eat the flesh of all clean animals and also of fowls, and drink liquor, and will take cooked food from the higher castes, including Sunārs and Kunbis. Hence they do not rank high socially, and Brāhmans do not take water from them, but their religious character gives them some prestige. Many Gosains have become landholders, obtaining their estates either as charitable grants from clients or through moneylending transactions. In this capacity they do not usually turn out well, and are often considered harsh landlords and grasping creditors.

Gowāri

1. Origin of the caste

Gowāri.114—The herdsman or grazier caste of the Marātha country, corresponding to the Ahīrs or Gaolis. The name is derived from gai or gao, the cow, and means a cowherd. The Gowāris numbered more than 150,000 persons in 1911, of whom nearly 120,000 belonged to the Nāgpur division and nearly 30,000 to Berār. In localities where the Gowāris predominate, Ahīrs or Gaolis, the regular herdsman caste, are found only in small numbers. The honorific title of the Gowāris is Dhare, which is said to mean ‘One who keeps cattle.’ The Gowāris rank distinctly below the Ahīrs or Gaolis. The legend of their origin is that an Ahīr, who was tending the cows of Krishna, stood in need of a helper. He found a small boy in the forest and took him home and brought him up. He then gave to the boy the work of grazing cows in the jungle, while he himself stayed at home and made milk and butter. This boy was the ancestor of the Gowāri caste. His descendants took to eating fowls and peacocks and drinking liquor, and hence were degraded below the Gaolis. But the latter will allow Gowāris to sit at their feasts and eat, they will carry the corpse of a Gowāri to the grave, and they will act as members of the panchāyat in readmitting a Gowāri who has been put out of caste. In the Marātha country any man who touches the corpse of a man of another caste is temporarily excommunicated, and the fact that a Gaoli will do this for a Gowāri demonstrates the close relationship of the castes. The legend, in fact, indicates quite clearly and correctly the origin of the Gowāris. The small boy in the forest was a Gond, and the Gowāri caste is of mixed descent from Ahīrs and Gonds. The Ahīrs or Gaolis of the Marātha country have largely abandoned the work of grazing cattle in the forest, and have taken to the more profitable business of making milk and ghī. The herdsman’s duties have been relegated to the mixed class of Gowāris, produced from the unions of Ahīrs and Gonds in the forests, and not improbably including a considerable section of pure Gond blood. At present only Gaolis and no other caste are admitted into the Gowāri community, though there is evidence that the rule was not formerly so strict.

2. Subcastes

The Gowāris have three divisions, the Gai Gowāri, Inga, and Māria or Gond Gowāri. The Gai or cow Gowāris are the highest and probably have more Gaoli blood in them. The Inga and Māria or Gond Gowāris are more directly derived from the Gonds. Māria is the name given to a large section of the Gond tribe in Chānda. Both the other two subcastes will take cooked food from the Gai Gowāris and the Gond Gowāris from the Inga, but the Inga subcaste will not take it from the Gond, nor the Gai Gowāris from either of the other two. The Gond Gowāris have been treated as a distinct caste and a separate article is given on them, but at the census Mr. Marten has amalgamated them with the Gowāris. This is probably more correct, as they are locally held to be a branch of the caste. But their customs differ in some points from those of the other Gowāris. They will admit outsiders from any respectable caste and worship the Gond gods,115 and there seems no harm, therefore, in allowing the separate article on them to remain.

3. Totemism and exogamy

The Gowāris have exogamous sections of the titular and totemistic types, such as Chachania from chachan, a bird, Lohār from loha iron, Ambadāre a mango-branch, Kohria from the Kohri or Kohli caste, Sarwaina a Gond sept, and Rāwat the name of the Ahīr caste in Chhattīsgarh. Some septs do not permit intermarriage between their members, saying that they are Dūdh-Bhais or foster-brothers, born from the same mother. Thus the Chachania, Kohria, Senwaria, Sendua (vermilion) and Wāgare (tiger) septs cannot intermarry. They say that their fathers were different, but their mothers were related or one and the same. This is apparently a relic of polyandry, and it is possible that in some cases the Gonds may have allowed Ahīrs sojourning in the forest to have access to their wives during the period of their stay. If this was permitted to Ahīrs of different sections coming to the same Gond village in successive years, the offspring might be the ancestors of sections who consider themselves to be related to each other in the manner of the Gowāri sections.

Marriage is prohibited within the same section or kur, and between sections related to each other as Dūdh-Bhais in the manner explained above. A man can marry his daughter to his sister’s son, but cannot take her daughter for his son. The children of two sisters cannot be married.

4. Marriage customs

Girls are usually married after attaining maturity, and a bride-price is paid which is normally two khandis (800 lbs.) of grain, Rs. 16 to 20 in cash, and a piece of cloth. The auspicious date of the wedding is calculated by a Mahār Mohturia or soothsayer. Brāhmans are not employed, the ceremony being performed by the bhānya or sister’s son of either the girl’s father or the boy’s father. If he is not available, any one whom either the girl’s father or the boy’s father addresses as bhānja or nephew in the village, according to the common custom of addressing each other by terms of relationship, even though he may be no relative and belong to another caste, may be substituted; and if no such person is available a son-in-law of either of the parties. The peculiar importance thus attached to the sister’s son as a relation is probably a relic of the matriarchate, when a man’s sister’s son was his heir. The substitution of a son-in-law who might inherit in the absence of a sister’s son perhaps strengthens this view. The wedding is held mainly according to the Marātha ritual.116 The procession goes to the girl’s house, and the bridegroom is wrapped in a blanket and carries a spear, in the absence of which the wedding cannot be held. A spear is also essential among the Gonds. The ancestors of the caste are invited to the wedding by beating a drum and calling on them to attend. The original ancestors are said to be Kode Kodwan, the names of two Gond gods, Bāghoba (the tiger-god), and Meghnāth, son of Rāwan, the demon king of Ceylon, after whom the Gonds are called Rāwanvansi, or descendants of Rāwan. The wedding costs about Rs. 50, all of which is spent by the boy’s father. The girl’s father only gives a feast to the caste out of the amount which he receives as bride-price. Divorce and the remarriage of widows are permitted.

5. Funeral rites

The dead are either buried or burnt, burial being more common. The corpse is laid with head to the south and feet to the north. On returning from the funeral they go and drink at the liquor-shop, and then kill a cock on the spot where the deceased died, and offer some meat to his spirit, placing it outside the house. The caste-fellows sit and wait until a crow comes and pecks at the food, when they think that the deceased has enjoyed it, and begin to eat themselves. If no crow comes before night the food may be given to a cow, and the party can then begin to eat. When the next wedding is held in the family, the deceased is brought down from the skies and enshrined among the deified ancestors.

6. Religion

The principal deities of the Gowāris are the Kode Kodwan or deified ancestors. They are worshipped at the annual festivals, and also at weddings. When a man or woman dies without children their spirits are known as Dhal, and are worshipped in the families to which they belonged. A male Dhal is represented by a stick of bamboo with one cross-piece at the top, and a female Dhal by a stick with two others crossing each other lashed to it at the top. These sticks are worshipped at the Diwāli festival, and carried in procession. Dudhera is a godling worshipped for the protection of cattle. He is represented by a clay horse placed near a white ant-hill. If a cow stops giving milk her udder is smoked with the burning wood of a tree called sānwal, and this is supposed to drive away the spirits who drink the milk from the udder. All Gowāris revere the haryal, or green pigeon. They say that it gives a sound like a Gowāri calling his cows, and that it is a kinsman. They would on no account kill this bird. They say that the cows will go to a tree from which green pigeons are cooing, and that on one occasion when a thief was driving away their cows a green pigeon cooed from a tree, and the cows turned round and came back again. This is like the story of the sacred geese at Rome, who gave warning of the attack of the Goths.

7. Caste rules and the panchāyat

The head of the caste committee is known as Shendia, from shendi, a scalp-lock or pig-tail, perhaps because he is at the top of the caste as the scalp-lock is at the top of the head. The Shendia is elected, and holds office for life. He has to readmit offenders into caste by being the first to eat and drink with them, thus taking their sins on himself. On such occasions it is necessary to have a little opium, which is mixed with sugar and water, and distributed to all members of the caste. If the quantity is insufficient for every one to drink, the man responsible for preparing it is fined, and this mixture, especially the opium, is indispensable on all such occasions. The custom indicates that a sacred or sacrificial character is attributed to the opium, as the drinking of the mixture together is the sign of the readmission of a temporary outcaste into the community. After this has been drunk he becomes a member of the caste, even though he may not give the penalty feast for some time afterwards. The Ahīrs and Sunārs of the Marātha country have the same rite of purification by the common drinking of opium and water. A caste penalty is incurred for the removal of bitāl or impurity arising from the usual offences, and among others for touching the corpse of a man of any other caste, or of a buffalo, horse, cow, cat or dog, for using abusive language to a casteman at any meeting or feast, and for getting up from a caste feast without permission from the headman. For touching the corpse of a prohibited animal and for going to jail a man has to get his head, beard and whiskers shaved. If a woman becomes with child by a man of another caste, she is temporarily expelled, but can be readmitted after the child has been born and she has disposed of it to somebody else. Such children are often made over for a few rupees to Muhammadans, who bring them up as menial servants in their families, or, if they have no child of their own, sometimes adopt them. On readmission a lock of the woman’s hair is cut off. In the same case, if no child is born of the liaison, the woman is taken back with the simple penalty of a feast. Permanent expulsion is imposed for taking food from, or having an intrigue with a member of an impure caste as Mādgi, Mehtar, Pardhān, Mahār and Māng.

8. Social customs

The Gowāris eat pork, fowls, rats, lizards and peacocks, and abstain only from beef and the flesh of monkeys, crocodiles and jackals. They will take food from a Māna, Marār or Kohli, and water from a Gond. Kunbis will take water from them, and Gonds, Dhīmars and Dhobis will accept cooked food. All Gowāri men are tattooed with a straight vertical line on the forehead, and many of them have the figures of a peacock, deer or horse on the right shoulder or on both shoulders. A man without the mark on the forehead will scarcely be admitted to be a true Gowāri, and would have to prove his birth before he was allowed to join a caste feast. Women are tattooed with a pattern of straight and crooked lines on the right arm below the elbow, which they call Sīta’s arm. They have a vertical line standing on a horizontal one on the forehead, and dots on the temples.

Gūjar

1. Historical notice of the caste

Gūjar.—A great historical caste who have given their name to the Gujarāt District and the town of Gujarānwāla in the Punjab, the peninsula of Gujarāt or Kāthiāwār and the tract known as Gūjargarh in Gwālior. In the Central Provinces the Gūjars numbered 56,000 persons in 1911, of whom the great majority belonged to the Hoshangābād and Nimār Districts. In these Provinces the caste is thus practically confined to the Nerbudda Valley, and they appear to have come here from Gwālior probably in the middle of the sixteenth century, to which period the first important influx of Hindus into this area has been ascribed. But some of the Nimār Gūjars are immigrants from Gujarāt. Owing to their distinctive appearance and character and their exploits as cattle-raiders, the origin of the Gūjars has been the subject of much discussion. General Cunningham identified them with the Yueh-chi or Tochāri, the tribe of Indo-Scythians who invaded India in the first century of the Christian era. The king Kadphises I. and his successors belonged to the Kushān section of the Yueh-chi tribe, and their rule extended over north-western India down to Gujarāt in the period 45–225 A.D. Mr. V. A. Smith, however, discards this theory and considers the Gūjars or Gurjaras to have been a branch of the white Huns who invaded India in the fifth and sixth centuries. He writes:117 “The earliest foreign immigration within the limits of the historical period which can be verified is that of the Sakas in the second century B.C.; and the next is that of the Yueh-chi and Kushāns in the first century A.D. Probably none of the existing Rājpūt clans can carry back their genuine pedigrees so far. The third recorded great irruption of foreign barbarians occurred during the fifth century and the early part of the sixth. There are indications that the immigration from Central Asia continued during the third century, but, if it did, no distinct record of the event has been preserved, and, so far as positive knowledge goes, only three certain irruptions of foreigners on a large scale through the northern and north-western passes can be proved to have taken place within the historical period anterior to the Muhammadan invasions of the tenth and eleventh centuries. The first and second, as above observed, were those of the Sakas and Yueh-chi respectively, and the third was that of the Hūnas or white Huns. It seems to be clearly established that the Hun group of tribes or hordes made their principal permanent settlements in the Punjab and Rājputāna. The most important element in the group after the Huns themselves was that of the Gurjaras, whose name still survives in the spoken form Gūjar as the designation of a widely diffused middle-class caste in north-western India. The prominent position occupied by Gurjara kingdoms in early mediaeval times is a recent discovery. The existence of a small Gurjara principality in Bharōch (Broach), and of a larger state in Rājputāna, has been known to archaeologists for many years, but the recognition of the fact that Bhoja and the other kings of the powerful Kanauj dynasty in the ninth, tenth and eleventh centuries were Gurjaras is of very recent date and is not yet general. Certain misreadings of epigraphic dates obscured the true history of that dynasty, and the correct readings have been established only within the last two or three years. It is now definitely proved that Bhoja (circ. A.D. 840–890), his predecessors and successors belonged to the Pratihāra (Parihār) clan of the Gurjara tribe or caste, and, consequently, that the well-known clan of Parihār Rājpūts is a branch of the Gurjara or Gūjar stock.”118