полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

The Gonds can now count up to twenty, and beyond that they use the word kori or a score, in talking of cattle, grain or rupees, so that this, perhaps, takes them up to twenty score. They say they learnt to count up to twenty on their ten fingers and ten toes.

60. Villages and houses

When residing in the centre of a Hindu population the Gonds inhabit mud houses, like the low-class Hindus. But in the jungles their huts are of bamboo matting plastered with mud, with thatched roofs. The internal arrangements are of the simplest kind, comprising two apartments separated from each other by a row of tall baskets, in which they store up their grain. Adjoining the house is a shed for cattle, and round both a bamboo fence for protection from wild beasts. In Bastar the walls of the hut are only four or five feet high, and the door three feet. Here there are one or two sheds, in which all the villagers store their grain in common, and no man steals another’s grain. In Gond villages the houses are seen perched about on little bluffs or other high ground, overlooking the fields, one, two and three together. The Gond does not like to live in a street. He likes a large bāri or fenced enclosure, about an acre in size, besides his house. In this he will grow mustard for sale, or his own annual supply of tobacco or vegetables. He arranges that the village cattle shall come and stand in the bāri on their way to and from pasture, and that the cows shall be milked there for some time. His family also perform natural functions in it, which the Hindus will not do in their fields. Thus the bāri gets well manured and will easily give two crops in the year, and the Gond sets great store by this field. When building a new house a man plants as the first post a pole of the sāj tree, and ties a bundle of thatching-grass round it, and buries a pice (¼d.) and a bhilawa nut beneath it. They feed two or three friends and scatter a little of the food over the post. The post is called Khirkhut Deo, and protects the house from harm.

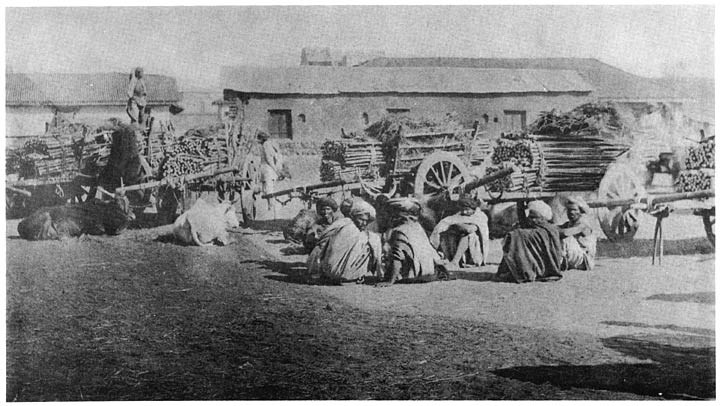

Gonds with their bamboo carts at market

A brass or pewter dish and lota or drinking-vessel of the same material, a few earthen cooking-pots, a hatchet and a clay chilam or pipe-bowl comprise the furniture of a Gond.

61. Clothes and ornaments

In Sir R. Jenkins’ time, a century ago, the Gonds were represented as naked savages, living on roots and fruits, and hunting for strangers to sacrifice. About fifty years later, when Mr. Hislop wrote, the Māria women of the wilder tracts were said only to have a bundle of leafy twigs fastened with a string round their waist to cover them before and behind. Now men have a narrow strip of cloth round the waist and women a broader one, but in the south of Bastar they still leave their breasts uncovered. Here a woman covers her breasts for the first time when she becomes pregnant, and if a young woman did it, she would be thought to be big with child. In other localities men and women clothe themselves more like Hindus, but the women leave the greater part of the thighs bare, and men often have only one cloth round the loins and another small rag on the head. They have bangles of glass, brass and zinc, and large circlets of brass round the legs, though these are now being discarded. In Bastar both men and women have ten to twenty iron and brass hoops round their necks, and on to these rings of the same metal are strung. Rai Bahādur Panda Baijnāth counted 181 rings on one hoop round an old woman’s neck. In the Māria country the boys have small separate plots of land, which they cultivate themselves and use the proceeds as their pocket-money, and this enables them to indulge in a profusion of ornaments sometimes exceeding those worn by the girls. In Mandla women wear a number of strings of yellow and bluish-white beads. A married woman has both colours, and several cowries tied to the end of the necklace. Widows and girls may only wear the bluish-white beads without cowries, and a remarried widow may not have any yellow beads, but she can have one cowrie on her necklace. Yellow beads are thus confined to married women, yellow being the common wedding-colour. A Gond woman is not allowed to wear a choli or little jacket over the breasts. If she does she is put out of caste. This rule may arise from opposition to the adoption of Hindu customs and desire to retain a distinctive feature of dress, or it may be thought that the adoption of the choli might make Gond women weaker and unfitted for hard manual labour, like Hindu women. A Gond woman must not keep her cloth tucked up behind into her waist when she meets an elderly man of her own family, but must let it down so as to cover the upper part of her legs. If she omits to do this, on the occasion of the next wedding the Bhumka or caste priest will send some men to catch her, and when she is brought the man to whom she was disrespectful will put his right hand on the ground and she must make obeisance to it seven times, then to his left hand, then to a broom and pestle, and so on till she is tired out. When they have a sprain or swelling of the arm they make a ring of tree-fibre and wear this on the arm, and think that it will cure the sprain or swelling.

62. Ear-piercing

The ears of girls are pierced by a thorn, and the hole is enlarged by putting in small pieces of wood or peacock’s feathers. Gond women wear in their ears the tarkhi or a little slab in shape like a palm-leaf, covered with coloured glass and fixed on to a stalk of hemp-fibre nearly an inch thick, which goes through the ear; or they wear the silver shield-shaped ornament called dhāra, which is described in the article on Sunār. In Bastar the women have their ears pierced in a dozen or more places, and have a small ring in each hole. If a woman gets her ear torn through she is simply put out of caste and has to give a feast for readmission, and is not kept out of caste till it heals, like a Hindu woman.

63. Hair

Gond men now cut their hair. Before scissors were obtainable it is said that they used to tie it up on their heads and chop off the ends with an axe, or burn them off. But the wilder Gonds often wear their hair long, and as it is seldom combed it gets tangled and matted. The Pandas or priests do not cut their hair. Women wear braids of false hair, of goats or other animals, twisted into their own to improve their appearance. In Mandla a Gond girl should not have her hair parted in the middle till she is married. When she is married this is done for the first time by the Baiga, who subsequently tattoos on her forehead the image of Chandi Māta.89

64. Bathing and washing clothes

Gonds, both men and women, do not bathe daily, but only wash their arms and legs. They think a complete bath once a month is sufficient. If a man gets ill he may think the god is angry with him for not bathing, and when he recovers he goes and has a good bath, and sometimes gives a feast. Hindus say that a Gond is only clean in the rains, when he gets a compulsory bath every day. In Bastar they seldom wash their clothes, as they think this impious, or else that the cloth would wear out too quickly if it were often washed. Here they set great store by their piece of cloth, and a woman will take it off before she cleans up her house, and do her work naked. It is probable that these wild Gonds, who could not weave, regarded the cloth as something miraculous and sacred, and, as already seen, the god Pālo is a piece of cloth.90

65. Tattooing

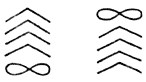

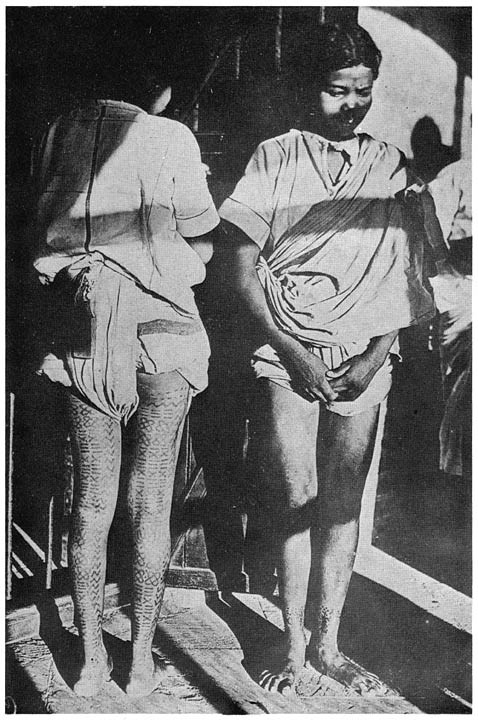

Both men and women were formerly much tattooed among the Gonds, though the custom is now going out among men. Women are tattooed over a large part of the body, but not on the hips or above them to the waist. Sorcerers are tattooed with some image or symbol of their god on their chest or right shoulder, and think that the god will thus always remain with them and that any magic directed against them by an enemy will fail. A woman should be tattooed at her father’s house, if possible before marriage, and if it is done after marriage her parents should pay for it. The tattooing is done with indigo in black or blue, and is sometimes a very painful process, the girl being held down by her friends while it is carried out. Loud shrieks, Forsyth says, would sometimes be heard by the traveller issuing from a village, which proclaimed that some young Gondin was being operated upon with the tattooing-needle. Patterns of animals and also common articles of household use are tattooed in dots and lines. In Mandla the legs are marked all the way up behind with sets of parallel lines, as shown above. These are called ghāts or steps, and sometimes interspersed at intervals is another figure called sānkal or chain. Perhaps their idea is to make the legs strong for climbing.

66. Special system of tattooing

Tattooing seems to have been originally a magical means of protecting the body against real and spiritual dangers, much in the same manner as the wearing of ornaments. It is also supposed that people were tattooed with images of their totem in order the better to identify themselves with it. The following account is stated to have been taken from the Baiga priest of a popular shrine of Devi in Mandla. His wife was a tattooer of both Baigas and Gonds, and considered it the correct method for the full tattooing of a woman, though very few women can nowadays be found with it. The magical intent of tattooing is here clearly brought out:—

On the sole of the right foot is the annexed device:

It represents the earth, and will have the effect of preventing the woman’s foot from being bruised and cut when she walks about barefoot.

On the sole of the left foot is this pattern:

It is meant to be in the shape of a foot, and is called Padam Sen Deo or the Foot-god. This deity is represented by stones marked with two footprints under a tree outside the village. When they have a pain in the foot they go to him, rub his two stones together and sprinkle the dust from them on their feet as a means of cure. The device tattooed on the foot no doubt performs a similar protective function.

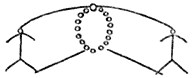

On the upper part of the foot five dots are made, one on each toe, and a line is drawn round the foot from the big toe to the little toe. This sign is said to represent Gajkaran Deo, the elephant god, who resides in cemeteries. He is a strong god, and it is probably thought that his symbol on the feet will enable them to bear weight. On the legs behind they have the images of the Baiga priest and priestess. These are also supposed to give strength for labour, and when they cannot go into the forest from fever or weakness they say that Bura Deo, as the deified priest is called, is angry with them. On the upper legs in front they tattoo the image of a horse, and at the back a saddle between the knee and the thigh. This is Koda Deo the horse-god, whose image will make their thighs as strong as those of a horse. If they have a pain or weakness in the thigh they go and worship Koda Deo, offering him a piece of saddle-cloth. On the outer side of each upper arm they tattoo the image of Hanumān, the deified monkey and the god of strength, in the form of a man. Both men and women do this, and men apply burning cowdung to the tattoo-mark in order to burn it effectually into the arm. This god makes the arms strong to carry weights. Down the back is tattooed an oblong figure, which is the house of the god Bhimsen, with an opening at the lower end just above the buttocks to represent the gate. Inside this on the back is the image of Bhimsen’s club, consisting of a pattern of dots more or less in the shape of an Indian club. Bhimsen is the god of the cooking-place, and the image of his club, in white clay stained green with the leaves of the semar tree, is made on the wall of the kitchen. If they have no food, or the food is bad, they say that Bhimsen is angry with them. The pattern tattooed on the back appears therefore to be meant to facilitate the digestion of food, which the Gonds apparently once supposed to pass down the body along the back. On the breast in front women tattoo the image of Bura Deo, as shown, the head on her neck and the body finishing at her breast-bone. The marks round the body represent stones, because the symbol of Bura Deo is sometimes a basket plastered with mud and filled with stones. On each side of the body women have the image of Jhulān Devi, the cradle goddess, as shown by the small figures attached to Bura Deo. But a woman cannot have the image of Jhulān Devi tattooed on her till she has borne a child. The place where the image is tattooed is that where a child rests against its mother’s body when she carries it suspended in her cloth, and it is supposed that the image of the goddess supports and protects the child, while the mother’s arms are left free for work.

Gond women, showing tattooing on backs of legs

Round the neck they have Kanteshwar Māta, the goddess of the necklace. She consists of three to six lines of dots round the neck representing bead necklaces.

On the face below the mouth there is sometimes the image of a cobra, and it is supposed that this will protect them from the effects of eating any poisonous thing.

On the forehead women have the image of Chāndi Māta. This consists of a dot at the forehead at the parting of the hair, from which two lines of dots run down to the ears on each side, and are continued along the sides of the face to the neck. This image can only be tattooed after the hair of a woman has been parted on her marriage, and they say that Chāndi Māta will preserve and guard the parting of the hair, that is the life of the woman’s husband, because the parting can only be worn so long as her husband is alive. Chāndi means the moon, and it seems likely that the parting of the hair may be considered to represent the bow of the moon.

The elaborate system of tattooing here described is rarely found, and it is perhaps comparatively recent, having been devised by the Baiga and Pardhān priests as their intelligence developed and their theogony became more complex.

67. Branding

Men are accustomed to brand themselves on the joints of the wrists, elbows and knees with burning wood of the semar tree from the Holi fire in order to render their joints supple for dancing. It would appear that the idea of suppleness comes from the dancing of the flames or the swift burning of the fire, while the wood is also of very light weight. Men are also accustomed to burn two or three marks on each wrist with a piece of hare’s dung, perhaps to make the joints supple like the legs of a hare.

68. Food

The Gonds have scarcely any restriction on diet. They will eat fowls, beef, pork, crocodiles, certain kinds of snakes, lizards, tortoises, rats, cats, red ants, jackals and in some places monkeys. Khatola and Rāj-Gonds usually abstain from beef and the flesh of the buffalo and monkey. They consider field-mice and rats a great delicacy, and will take much trouble in finding and digging out their holes. The Māria Gonds are very fond of red ants, and in Bastar give them fried or roasted to a woman during her confinement. The common food of the labouring Gond is a gruel of rice or small millet boiled in water, the quantity of water increasing in proportion to their poverty. This is about the cheapest kind of food on which a man can live, and the quantity of grain taken in the form of this gruel or pej which will suffice for a Gond’s subsistence is astonishingly small. They grow the small grass-millets kodon and kutki for their subsistence, selling the more valuable crops for rent and expenses. The flowers of the mahua tree are also a staple article of diet, being largely eaten as well as made into liquor, and the Gond knows of many other roots and fruits of the forest. He likes to eat or drink his pej several times a day, and in Seoni, it is said, will not go more than three hours without a meal.

Gonds are rather strict in the matter of taking food from others, and in some localities refuse to accept it even from Brāhmans. Elsewhere they will take it from most Hindu castes. In Hoshangābād the men may take food from the higher Hindu castes, but not the women. This, they say, is because the woman is a wooden vessel, and if a wooden vessel is once put on the fire it is irretrievably burnt. A woman similarly is the weaker vessel and will sustain injury from any contamination. The Rāj-Gond copies Hindu ways and outdoes the Hindu in the elaboration of ceremonial purity, even having the fuel with which his Brāhman cook prepares his food sprinkled with water to purify it before it is burnt. Mr. A. K. Smith states that a Gond will not eat an antelope if a Chamār has touched it, even unskinned, and in some places they are so strict that a wife may not eat her husband’s leavings of food. The Gonds will not eat the leavings of any Hindu caste, probably on account of a traditional hostility arising out of their subjection by the Hindus. Very few Hindu castes will take water or food from the Gonds, but some who employ them as farmservants do this for convenience. The Gonds are not regarded as impure, even though from a Hindu point of view some of their habits are more objectionable than those of the impure castes. This is because the Gonds have never been completely reduced to subjection, nor converted into the village drudges, who are consigned to the most degraded occupations. Large numbers of them hold land as tenants and estates as zamīndārs; and the greater part of the Province was once governed by Gond kings. The Hindus say that they could not consider a tribe as impure to which their kings once belonged. Brāhmans will take water from Rāj-Gonds and Khatola Gonds in many localities. This is when it is freshly brought from the well and not after it has been put in their houses.

69. Liquor

Excessive drinking is the common vice of the Gonds and the principal cause which militates against their successfully competing with the Hindus. They drink the country spirit distilled from the flowers of the mahua tree, and in the south of the Province toddy or the fermented juice of the date-palm. As already seen, in Bastar their idea of hell is a place without liquor. The loss of the greater part of the estates formerly held by Gond proprietors has been due to this vice, which many Hindu liquor-sellers have naturally fostered to their own advantage. No festival or wedding passes without a drunken bout, and in Chānda at the season for tapping the date-palm trees the whole population of a village may be seen lying about in the open dead drunk. They impute a certain sanctity to the mahua tree, and in some places walk round a post of it at their weddings. Liquor is indispensable at all ceremonial feasts, and a purifying quality is attributed to it, so that it is drunk at the cemetery or bathing-ghāt after a funeral. The family arranges for liquor, but mourners attending from other families also bring a bottle each with them, if possible. Practically all the events of a Gond’s life, the birth of a child, betrothals and weddings, recovery from sickness, the arrival of a guest, bringing home the harvest, borrowing money or hiring bullocks, and making contracts for cultivation, are celebrated by drinking. And when a Gond has once begun to drink, if he has the money he usually goes on till he is drunk, and this is why the habit is such a curse to him. He is of a social disposition and does not like to drink alone. If he has drunk something, and has no more money, and the contractor refuses to let him have any more on credit as the law prescribes, the Gond will sometimes curse him and swear never to drink in his shop again. Nevertheless, within a few days he will be back, and when chaffed about it will answer simply that he could not resist the longing. In spite of all the harm it does him, it must be admitted that it is the drink which gives most of the colour and brightness to a Gond’s life, and without this it would usually be tame to a degree.

When a Gond drinks water from a stream or tank, he bends down and puts his mouth to the surface and does not make a cup with his hands like a Hindu.

70. Admission of outsiders and sexual morality

Outsiders are admitted into the tribe in some localities in Bastar, and also the offspring of a Gond man or woman with a person of another caste, excepting the lowest. But some people will not admit the children of a Gond woman by a man of another caste. Not much regard is paid to the chastity of girls before marriage, though in the more civilised tracts the stricter Hindu views on the subject are beginning to prevail. Here it is said that if a girl is detected in a sexual intrigue before marriage she may be taken into caste, but may not participate in the worship of Bura Deo nor of the household god. But this is probably rather a counsel of perfection than a rule actually enforced. If a daughter is taken in the sexual act, they think some misfortune will happen to them, as the death of a cow or the failure of crops. Similarly the Māria Gonds think that if tigers kill their cattle it is a punishment for the adultery of their wives, and hence if a man loses a head or two he looks very closely after his wife, and detection is often followed by murder. Here probably adultery was originally considered an offence as being a sin against the tribe, because it contaminated the tribal blood, and out of this attitude marital jealousy has subsequently developed. Speaking generally, the enforcement of rules of sexual morality appears to be comparatively recent, and there is no doubt that the Baigas and other tribes who have lived in contact with the Gonds, as well as the Ahīrs and other low castes, have a large admixture of Gond blood. In Bastar a Gond woman formerly had no feelings of modesty as regards her breasts, but this is now being acquired. Laying the hand on a married woman’s shoulder gives great offence. Mr. Low writes:91 “It is difficult to say what is not a legal marriage from a Gond point of view; but in spite of this laxity abductions are frequent, and Colonel Bloomfield mentions one particularly noteworthy case where the abductor, an unusually ugly Gond with a hare-lip, was stated by the complainant to have taken off first the latter’s aunt, then his sister and finally his only wife.”

71. Common sleeping-houses

Many Gond villages in Chhattīsgarh and the Feudatory States have what is known as a gotalghar. This is a large house near the village where unmarried youths and maidens collect and dance and sing together at night. Some villages have two, one for the boys and one for the girls. In Bastar the boys have a regular organisation, their captain being called Sirdār, and the master of the ceremonies Kotwār, while they have other officials bearing the designation of the State officers. After supper the unmarried boys go first to the gotalghar and are followed by the girls. The Kotwār receives the latter and directs them to bow to the Sirdār, which they do. Each girl then takes a boy and combs his hair and massages his hands and arms to refresh him, and afterwards they sing and dance together until they are tired and then go to bed. The girls can retire to their own house if they wish, but frequently they sleep in the boys’ house. Thus numerous couples become intimate, and if on discovery the parents object to their marriage, they run away to the jungle, and it has to be recognised. In some villages, however, girls are not permitted to go to the gotalghar. In one part of Bastar they have a curious rule that all males, even the married, must sleep in the common house for the eight months of the open season, while their wives sleep in their own houses. A Māria Gond thinks it impious to have sexual intercourse with his wife in his house, as it would be an insult to the goddess of wealth who lives in the house, and the effect would be to drive her away. Their solicitude for this goddess is the more noticeable, as the Māria Gond’s house and furniture probably constitute one of the least valuable human habitations on the face of the globe.