полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

Gond-Gowāri

Gond-Gowāri.96—A small hybrid caste formed from alliances between Gonds and Gowāris or herdsmen of the Marātha country. Though they must now be considered as a distinct caste, being impure and thus ranking lower than either the Gonds or Gowāris, they are still often identified with either of them. In 1901 only 3000 were returned, principally from the Nāgpur and Chānda Districts. In 1911 they were amalgamated with the Gowāris, and this view may be accepted as their origin is the same. The Gowāris say that the Gond-Gowāris are the descendants of one of two brothers who accidentally ate the flesh of a cow. Both the Gonds and Gowāris frequent the jungles for long periods together, and it is natural that intimacies should spring up between the youth of either sex. And the progeny of these irregular connections has formed a separate caste, looked down upon by both its progenitors. The Gond-Gowāris have no subcastes, and for purposes of marriages are divided into exogamous septs, all bearing Gond names. Like the Gonds, the caste is also split into two divisions, worshipping six and seven gods respectively, and members of septs worshipping the same number of gods must not marry with each other. The deities of the six and seven god-worshippers are identical, except that the latter have one extra called Durga or Devi, who is represented by a copper coin of the old Nāgpur dynasty. Of the other deities Būra Deo is a piece of iron, Khoda and Khodāvan are both pieces of the kadamb tree (Nauclea parvifolia), Supāri is the areca-nut, and Kaipen consists of two iron rings and counts as two deities. It seems probable, therefore, from the double set of identical deities that two of the original ones have been forgotten. The gods are kept on a small piece of red cloth in a closed bamboo basket, which must not be opened except on days of worship, lest they should work some mischief; on these special days they are rendered harmless for the time being by the homage which is rendered to them. Marriage is adult, and a bride-price of nine rupees and some grain is commonly paid by the boy’s family. The ceremony is a mixture of Gond and Marātha forms; the couple walk seven times round a bohla or mound of earth and the guests clap their hands. At a widow-marriage they walk three and a half times round a burning lamp, as this is considered to be only a kind of half-marriage. The morality of the caste is very loose, and a wife will commonly be pardoned any transgression except an intrigue with a man of very low caste. Women of other castes, such as Kunbis or Barhais, may be admitted to the community on forming a connection with a Gond-Gowāri. The caste have no prescribed observance of mourning for the dead. The Gond-Gowāris are cultivators and labourers, and dress like the Kunbis. They are considered to be impure and must live outside the village, while other castes refuse to touch them. The bodies of the women are disfigured by excessive tattooing, the legs being covered with a pattern of dots and lines reaching up to the thighs. In this matter they simply follow their Gond ancestors, but they say that a woman who is not tattooed is impure and cannot worship the deities.

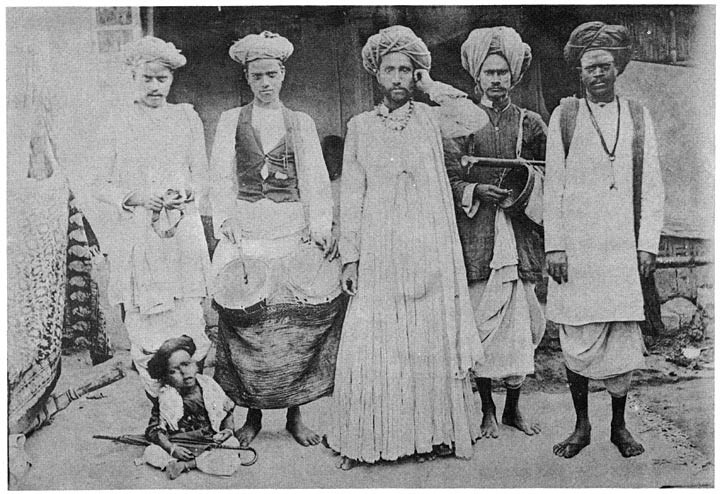

Gondhali musicians and dancers

Gondhali

Gondhali.97—A caste or order of wandering beggars and musicians found in the Marātha Districts of the Central Provinces and in Berār. The name is derived from the Marāthi word gondharne, to make a noise. In 1911 the Gondhalis numbered about 3000 persons in Berār and 500 in the Central Provinces, and they are also found in Bombay. The origin of the caste is obscure, but it appears to have been recruited in recent times from the offspring of Wāghyas and Murlis or male and female children devoted to temples by their parents in fulfilment of a vow. Mr. Kitts states in the Berār Census Report98 of 1881 that the Gondhalis are there attached either to the temple of Tukai at Tuljāpur or the temple of Renuka at Māhur, and in consequence form two subcastes, the Kadamrai and Renurai, who do not intermarry. In the Central Provinces, however, besides these two there are a number of other subcastes, most of which bear the names of distinct castes, and obviously consist of members of that caste who became Gondhalis, or of their descendants. Thus among the names of subcastes reported are the Brāhman, Marātha, Māne Kunbi, Khaire Kunbi, Teli, Mahār, Māng and Vidūr Gondhalis, as well as others like the Deshkars, or those coming from the Deccan, the Gangāpāre,99 or those from beyond the Ganges, and the Hijade or eunuchs. It is clear, therefore, that members of these castes becoming Gondhalis attempt to arrange their marriages with other converts from their own caste and to retain their relative social position. There is little doubt that all Gondhalis are theoretically meant to be equal, a principle which at their first foundation applies to nearly all sects and orders, but here as elsewhere the social feeling of caste has been too strong to permit of its retention. It may be doubted, however, whether in view of the small total numbers of the caste all these groups can be strictly endogamous. The Kunbi Gondhalis can take food from the ordinary Kunbis, but they rank below them, as being mendicants. The caste has also a number of exogamous groups or gotras, the names of which may be classified as titular or territorial. Instances of the former kind are Dokiphode or one who broke his head while begging, Sukt (thin, emaciated), Muke (dumb), Jabal (one with long hair like a Jogī), and Panchānge (one who has five limbs). Girls are married as a rule before adolescence, and the ceremony resembles that of the Kunbis, but a special prayer is offered to the deity Renuka, and the boy is invested with a necklace of cowries by five married men of the caste. Till this has been done he is not considered to be a proper Gondhali. Celibacy is not a tenet of the order. The remarriage of widows is allowed, and the ceremony consists in the husband placing a string of small black glass beads round the woman’s neck, while she holds out a pair of new shoes for him to put his feet into. The second wife often wears a small silver or golden image of the first wife round her neck, and worships it before she eats by touching it with food; she also asks its permission before going to sleep with her husband. The goddess Bhawāni or Devi is especially revered by the caste, and they fast in her honour on Tuesdays and Fridays. They worship their musical instruments at Dasahra with an offering of a goat, and afterwards sing and dance for the whole night, this being their principal festival. They also observe the nine days’ fasts in honour of Devi in Chait (March) and Kunwār (September) and sow the Jawaras or pots of wheat. The Gondhalis are mendicant musicians, and are engaged on the occasion of marriages among the higher castes to perform their gondhal or dance accompanied by music. Four men are needed for it, one being the dancer who is dressed in a long white robe with a necklace of cowries and bells on his ankles, while the other three stand behind him, two of them carrying drums and the third a sacred torch called dioti. The torch-bearer serves as a butt for the witticisms of the dancer. Their instruments are the chonka, an open drum carrying an iron string which is beaten with a small wooden pin, and two sambals or double drums of iron, wood or earth, one of which emits a dull and the other a sharp sound. The dance is performed in honour of the goddess Bhawāni. They set up a wooden stool on the stage arranged for the performance, covered with a cloth on which wheat is spread, and over this is placed a brass vessel containing water and a cocoanut. This represents the goddess. After the performance the Gondhalis take away and eat the cocoanut and wheat; their regular fee for an engagement is Rs. 1–4, and the guests give them presents of a few pice (farthings). They are engaged for important ceremonies such as marriages, the Bārsa or name-giving of a boy, and the Shantik or maturity of a girl, and also merely for entertainment; but in this case the stool and cocoanut representing the goddess are not set up. The following is a specimen of a Gondhali religious song:

Where I come from and who am I,This mystery none has solved;Father, mother, sister and brother, these are all illusions.I call them mine and am lost in my selfish concerns.Worldliness is the beginning of hell, man has wrapped himself in it without reason.Remember your guru, go to him and touch his feet.Put on the shield of mercy and compassion and take the sword of knowledge.God is in every human body.The caste beg between dawn and noon, wearing a long white or red robe and a red turban folded from twisted strings of cloth like the Marāthas. Their status is somewhat low, but they are usually simple and honest. Occasionally a man becomes a Gondhali in fulfilment of a vow without leaving his own caste; he will then be initiated by a member of the caste and given the necklace of cowries, and on every Tuesday he will wear this and beg from five persons in honour of the goddess Devi; while except for this observance he remains a member of his own caste and pursues his ordinary business.

Gopāl

Gopāl, Borekar.—Bibliography: Major Gunthorpe’s Criminal Tribes; Mr. Kitt’s Berār Census Report, 1881.

A small vagrant and criminal caste of Berār, where they numbered about 2000 persons in 1901. In the Central Provinces they were included among the Nats in 1901, but in 1891 a total of 681 were returned. Here they belong principally to the Nimār District, and Major Gunthorpe considers that they entered Berār from Nimār and Indore.

They are divided into five classes, the Marāthi, Vīr, Pangul, Pahalwān, or Khām, and Gujarāti Gopāls. The ostensible occupation of all the groups is the buying and selling of buffaloes. The word Gopāl means a cowherd and is a name of Krishna. The Marāthi Gopāls rank higher than the rest, and all other classes will take food from them, while the Vīr Gopāls eat the flesh of dead cattle and are looked down upon by the others. The ostensible occupation of the Vīr Gopāls is that of making mats from the leaves of the date-palm tree. They build their huts of date-leaves outside a village and remain there for one or two years or more until the headman tells them to move on. The name Borekar is stated to have the meaning of mat-maker. The Pāngul Gopāls also make mats, but in addition to this they are mendicants, begging from off trees, and must be the same as the Harbola mendicants of the Central Provinces. The Pāngul spreads a cloth below a tree and climbing it sits on some high branch in the early morning. Here he sings and chants the praises of charitable persons until somebody throws a small present on to the cloth. This he does only between cock-crow and sunrise and not after sunrise. Others walk through the streets, ejaculating dam!100 dam! and begging from door to door. With the exception of shaving after a death they never cut the hair either of their head or face. Their principal deity is Dāwal Mālik, but they also worship Khandoba; and they bury the bodies of their dead. The corpse is carried to the grave in a jholi or wallet and is buried in a sitting posture. In order to discover whether a dead ancestor has been reborn in a child they have recourse to magic. A lamp is suspended from a thread, and the upper stone of the grinding-mill is placed standing upon the lower one. If either of them moves when the name of the dead ancestor is pronounced they consider that he has been reborn. One section of the Pānguls has taken to agriculture, and these refuse to marry with the mendicants, though eating and drinking with them. The Pahalwān Gopāls live in small tents and travel about, carrying their belongings on buffaloes. They are wrestlers and gymnasts, and belong mainly to Hyderābād.101 The Khām Gopāls are a similar group also belonging to Hyderābād; and are so named because they carry about a long pole (khām) on which they perform acrobatic feats. They also have thick canvas bags, striped blue and white, in which they carry their property. The Gujarāti Gopāls are lower than the other divisions, who will not take food from them. They are tumblers and do feats of strength and also perform on the tight-rope. All five groups, Major Gunthorpe states, are inveterate cattle-thieves; and have colonies of their people settled on the Indore and Hyderābād borders and between them along the foot of the Satpūra Hills. Buffaloes or other animals which they steal are passed along from post to post and taken to foreign territory in an incredibly short space of time. A considerable proportion of them, however, have now taken to agriculture, and their proper traditional calling is to sell milk and butter, for which they keep buffaloes. Gopāl is a name of Krishna, and they consider themselves to be descended from the herdsmen of Brindāban.

Gosain

1. Names for the Gosains

Gosain, Gusain, Sanniāsi, Dasnāmi.102—A name for the orders of religious mendicants of the Sivite sect, from which a caste has now developed. In 1911 the Gosains numbered a little over 40,000 persons in the Central Provinces and Berār, being distributed over all Districts. The name Gosain signifies either gao-swāmi, master of cows, or go-swāmi, master of the senses. Its significance sometimes varies. Thus in Bengal the heads of Bairāgi or Vaishnava monasteries are called Gosain, and the priests of the Vishnuite Vallabhachārya sect are known as Gokulastha Gosain. But over most of India, as in the Central Provinces, Gosain appears to be a name applied to members of the Sivite orders. Sanniāsi means one who abandons the desires of the world and the body. Properly every Brāhman should become a Sanniāsi in the fourth stage or ashrām of his life, when after marrying and begetting a son to celebrate his funeral rites in the second stage, he should retire to the forest, become a hermit and conquer all the appetites and passions of the body in the third stage. Thereafter, when the process of mortification is complete he should beg his bread as a Sanniāsi. But only those who enter the religious orders now become Sanniāsis, and the name is therefore confined to them. Dasnāmi means the ten names, and refers to the ten orders in which the Gosains or Sivite anchorites are commonly classified. Sādhu is a generic term for a religious mendicant. The name Gosain is now more commonly applied to the married members of the caste, who pursue ordinary avocations, while the mendicants are known as Sādhu or Sanniāsi.

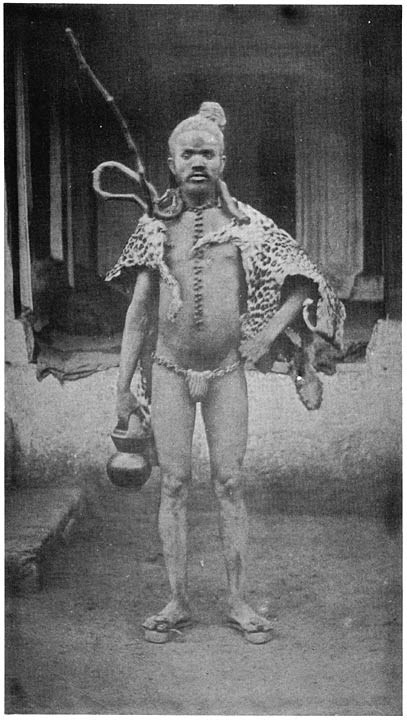

Gosain mendicant

2. The ten orders

The Gosains consider their founder to have been Shankar Achārya, the great apostle of the revival of the worship of Siva in southern India, who lived between the eighth and tenth centuries. He had four disciples from whom the ten orders of Gosains are derived. These are commonly stated as follows:

1. Giri (peak or top of a hill).

2. Puri (a town).

3. Parbat (a mountain).

4. Sāgar (the ocean).

5. Ban or Van (the forest).

6. Tīrtha (a shrine of pilgrimage).

7. Bhārthi (the goddess of speech).

8. Sāraswati (the goddess of learning).

9. Aranya (forest).

10. Ashrām (a hermitage).

The names may perhaps be held to refer to the different places in which the members of each order would pursue their austerities. The different orders have their headquarters at great shrines. The Sāraswati, Bhārthi and Puri orders are supposed to be attached to the monastery at Sringeri in Mysore; the Tīrtha and Ashrām to that at Dwārka in Gujarāt; the Ban and Aranya to the Govardhan monastery at Puri; and the Giri, Parbat and Sāgara to the shrine of Badrināth in the Himalayas.

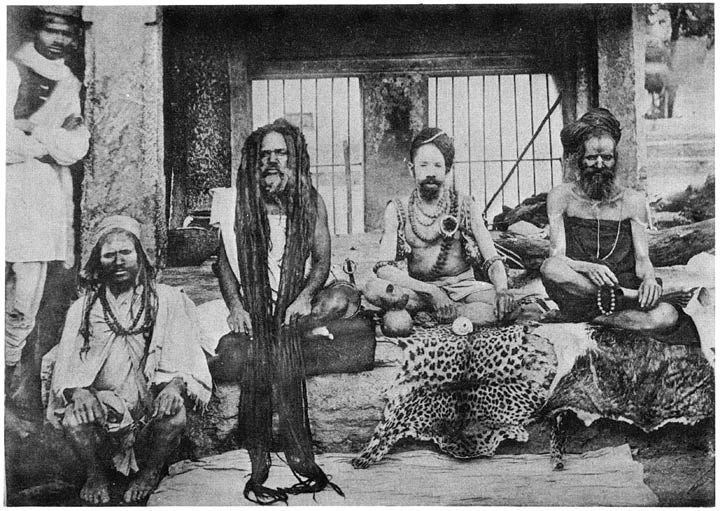

Alakhwāle Gosains with faces covered with ashes

Dandi is sometimes shown as one of the ten orders, but it seems to be the special designation of certain ascetics who carry a staff and may belong to either the Tīrtha, Ashrām, Bhārthi or Sāraswati groups. Another name for Gosain ascetics is Abdhūt, or one who has separated himself from the world. The term Abdhūt is sometimes specially applied to followers of the Marātha saint, Dattatreya, an incarnation of Siva.

The commonest orders in the Central Provinces are Giri, Puri and Bhārthi, and the members frequently use the name of the order as their surname. Members of the Aranya, Sāgara and Parbat orders are rarely met with at present.

3. Initiation

A notice of the Gosains who have become an ordinary caste will be given later. Formerly only Brāhmans or members of the twice-born castes could become Gosains, but now a man of any caste, as Kurmi, Kunbi or Māli, from whom a Brāhman takes water, may be admitted. In some localities it is said that Gonds and Kols can now be made Gosains, and hence the social position of the Gosains has greatly fallen, and high-caste Hindus will not take water from them. It is supposed, however, that the Giri order is still recruited only from Brāhmans.

At initiation the body of a neophyte is cleaned with the five products of the sacred cow, milk, curds, ghī, dung and urine. He drinks water in which the great toe of his guru has been dipped and eats the leavings of the latter’s food, thus severing himself from his own caste. His sacred thread is taken off and broken, and it is sometimes burned and he eats the ashes. All the hair of his head is shaved, including the scalp-lock, which every secular Hindu wears. A mantra or text is then whispered or blown into his ear.

4. Dress

The novice is dressed in a cloth coloured with geru or red ochre, such as the Gosains usually wear. It is probable that the red or pink colour is meant to symbolise blood and to signify that the Gosains allow the sacrifice of animals and the consumption of flesh, and on this account they are called Lāl Pādri or red priest, while Vishnuite mendicants, who dress in white, are called Sīta Pādri. He has a necklace or rosary of the seeds of the rudrāksha tree,103 sacred to Siva, consisting of 32 or 64 beads. These are like nuts with a rough indented shell. On his forehead he marks with bhabhūt or ashes three horizontal lines to represent the trident of Siva, or sometimes the eye of the god. Others make only two lines with a dot above or below, and this sign is said to represent the phallic emblem. A crescent moon or a triangle may also be made.104 The marks are often made in sandalwood, and the Gosains say that the original sandalwood grows on a tree in the Himalayas, which is guarded by a great snake so that nobody can approach it; but its scent is so strong that all the surrounding trees of the grove are scented with it and sandalwood is obtained from them. Those who worship Bhairon make a round mark with vermilion between the eyes, taking it from beneath the god’s foot. A mendicant usually has a begging-bowl and a pair of tongs, which are useful for kindling a fire. Those who have visited Badrināth or one of the other Himalayan shrines have a ring of iron, brass or copper on the arm, often inscribed with the image of a deity. If they have been to the temple of Devi at Hinglāj in the Lāsbela State of Beluchistān they have a necklace of little white stone beads called thumra; and one who has made a pilgrimage to Rāmeshwaram at the extreme southern point of India has a ring of conch-shell on the wrist. When he can obtain it a Gosain also carries a tiger- or panther-skin, which he wears over his shoulders and uses to sit and lie down on. Among the ancient Greeks it was the custom to sleep in a temple or its avenue either on the bare ground or on the skin of a sacred animal, in order to obtain visions or appearances of the god in a dream or to be cured of diseases.105 Formerly the Gosains were accustomed to go about naked, and at the religious festivals they would go in procession naked to bathe in the river. At Amarnāth in the Punjab they would throw themselves naked on the block of ice which represented Siva.106 The Nāga Gosains, so called because they were once accustomed to go naked into battle, were a famous fighting corps. Though they shave the head and scalp-lock on initiation the Gosains usually let the hair grow, and either have it hanging down in matted locks over the shoulders, which gives them a wild and unkempt appearance, or wind it on the top of the head into a coil often thickened with strips of sheep’s wool. They say that they let the hair grow in imitation of the ancient forest ascetics, who could not but let it grow as they had no means to shave it, and also of the matted locks of the god Siva. Sometimes they let the hair grow during the whole period of a pilgrimage, and on arrival at the shrine of their destination shave it off and offer it to the god. Those who are initiated on the banks of the Nerbudda throw the hair cut from their head into the sacred river.

Gosain mendicants with long hair

5. Methods of begging and greetings

They have various rules about begging. Some will never turn back to receive alms. They may also make a rule only to accept the surplus of food cooked for the family, and to refuse any of special quality or cooked expressly for them. One Gosain, noticed by Mr. A. K. Smith, always begged hopping, and only from five houses; he took from them respectively two handfuls of flour, a pinch of salt, and sufficient quantities of vegetables, spices and butter for his meal, and then went hopping home. Those who are performing the perikrama or circuit of the Nerbudda from its source to its mouth and back, do not cut their hair or nails during the whole period of about three years. They may not enter the Nerbudda above their knees nor wash their vessels in it. After crossing any tributary river or stream in their path they may not re-cross this; and if they have forgotten or left any article behind, must abandon it unless they can persuade somebody to go back and fetch it for them. Some carry a gourd with a single string stretched on a stick, on which they twang some notes; others have a belt of sheep’s hair hung with the bells of bullocks which they tie round the waist, so that the tinkling of the bells may announce their coming. A common begging cry is Alakh, which is said to mean ‘apart,’ and to refer to themselves as being apart or separated from the world. The beggar gives this cry and stands at the door of the house for half a minute, shaking his body about all the time. If no alms are brought in this time he moves on.

When an ordinary Hindu meets a Gosain he says ‘Nāmu Nārāyan’ or ‘I go to Nārāyan,’ and the Gosain answers ‘Nārāyan.’ Nārāyan is a name of Vishnu, and its use by the Gosains is curious. Those who have performed the circuit of the Nerbudda say ‘Har Nerbudda,’ and the person addressed answers ‘Nerbudda Mai ki Jai’ or ‘Victory to Mother Nerbudda.’

6. The Dandis

The Dandis are a special group of ascetics belonging to several of the ten orders. According to one account a novice who desires to become a Sanniāsi must serve a period of probation for twelve years as a Dandi. Others say that only a Brāhman can be a Dandi, while members of other castes may become Sanniāsis, and a Brāhman can only become one if he is without father, mother, wife or child.107 The Dandi is so called because he has a dand or bamboo staff like the ancient Vedic students. He must always carry this and never lay it down, but when sleeping plant it in the ground. Sometimes a piece of red cloth is tied round the staff. The Dandi should live in the forest, and only come once a day to beg at a Brāhman’s house for a part of such food as the family may have cooked. He should not ask for food if any one else, even a dog, is waiting for it. He must not accept money, or touch fire or any metal. As a matter of fact these rules are disregarded, and the Dandi frequents towns and is accompanied by companions who will accept all kinds of alms on his behalf.108 Dandis and Sanniāsis do not worship idols, as they are themselves considered to have become part of the deity. They repeat the phrase ‘Sevoham,’ which signifies ‘I am Siva.’