полная версия

полная версияThe Children of the Poor

The story of the tough’s career I told in “How the Other Half Lives,” and there is no need of repeating it here. Its end is generally lurid, always dramatic. It is that even when it comes to him “with his boots off,” in a peaceful sick bed. In his bravado one can sometimes catch a glimpse of the sturdiest traits in the Celtic nature, burlesqued and caricatured by the tenement. One who had been a cut-throat, bruiser, and prizefighter all his brief life lay dying from consumption in his Fourth Ward tenement not long ago. He had made what he proudly called a stand-up fight against the disease until now the end had come and he had at last to give up.

“Maggie,” he said, turning to his wife with eyes growing dim, “Mag! I had an iron heart, but now it is broke. Watch me die!” And Mag told it proudly at the wake as proof that Pat died game.

And the girl that has come thus far with him? Fewer do than one might think. Many more switch off their lovers to some honest work this side of the jail, making decent husbands of them as they are loyal wives, thus proving themselves truly their better halves. But of her who goes his way with him—it is not generally a long way for either—what of her end? Let me tell the story of one that is the story of all. I came across it in the course of my work as a newspaper man a year ago and I repeat it here as I heard it then from those who knew, with only the names changed. The girl is dead, but he is alive and leading an honest life at last, so I am told. The story is that of “Kid” McDuff’s girl.

CHAPTER V.

THE STORY OF KID McDUFF’S GIRL

THE back room of the saloon on the northwest corner of Pell Street and the Bowery is never cheery on the brightest day. The entrance to the dives of Chinatown yawns just outside, and in the bar-room gather the vilest of the wrecks of the Bend and the Sixth Ward slums. But on the morning of which I speak a shadow lay over it even darker than usual. The shadow of death was there. In the corner, propped on one chair, with her feet on another, sat a dead woman. Her glassy eyes looked straight ahead with a stony, unmeaning stare until the policeman who dozed at a table at the other end of the room, suddenly waking up and meeting it, got up with a shudder and covered the face with a handkerchief.

What did they see, those dead eyes? Through its darkened windows what a review was the liberated spirit making of that sin-worn, wasted life, begun in innocence and wasted—there? Whatever their stare meant, the policeman knew little of it and cared less.

“Oh! it is just a stiff,” he said, and yawned wearily. There was still half an hour of his watch.

The clinking of glasses and the shuffle of cowhide boots on the sanded floor outside grew louder and was muffled again as the door leading to the bar was opened and shut by a young woman. She lingered doubtfully on the threshold a moment, then walked with unsteady step across the room toward the corner where the corpse sat. The light that struggled in from the gloomy street fell upon her and showed that she trembled, as if with the ague. Yet she was young, not over twenty-five; but on her heavy eyes and sodden features there was the stamp death had just blotted from the other’s face with the memory of her sins. Yet, curiously blended with it, not yet smothered wholly, there was something of the child, something that had once known a mother’s love and pity.

“Poor Kid,” she said, stopping beside the body and sinking heavily in a chair. “He will be sorry, anyhow.”

“Who is Kid?” I asked.

“Why, Kid McDuff! You know him? His brother Jim keeps the saloon on – Street. Everybody knows Kid.”

“Well, what was she to Kid?” I asked, pointing to the corpse.

“His girl,” she said promptly. “An’ he stuck to her till he was pulled for the job he didn’t do; then he had to let her slide. She stuck to him too, you bet.

“Annie wasn’t no more nor thirteen when she was tuk away from home by the Kid,” the girl went on, talking as much to herself as to me; the policeman nodded in his chair. “He kep’ her the best he could, ’ceptin’ when he was sent up on the Island the time the gang went back on him. Then she kinder drifted. But she was all right agin he come back and tuk to keepin’ bar for his brother Jim. Then he was pulled for that Bridgeport skin job, and when he went to the pen she went to the bad, and now–”

Here a thought that had been slowly working down through her besotted mind got a grip on her strong enough to hold her attention, and she leaned over and caught me by the sleeve, something almost akin to pity struggling in her bleary eyes.

“Say, young feller,” she whispered hoarsely, “don’t spring this too hard. She’s got two lovely brothers. One of them keeps a daisy saloon up on Eighth Avenue. They’re respectable, they are.”

Then she went on telling what she knew of Annie Noonan who was sitting dead there before us. It was not much. She was the child of an honest shoemaker who came to this country twenty-two or three years before from his English home, when Annie was a little girl of six or seven. Before she was in her teens she was left fatherless. At the age of thirteen, when she was living in an East Side tenement with her mother, the Kid, then a young tough qualifying with one of the many gangs about the Hook for the penitentiary, crossed her path. Ever after she was his slave, and followed where he led.

The path they trod together was not different from that travelled by hundreds of young men and women to-day. By way of the low dives and “morgues” with which the East Side abounds, it led him to the Island and her to the street. When he was sent up the first time, his mother died of a broken heart. His father, a well-to-do mechanic in the Seventh Ward, had been spared that misery. He had died before the son was fairly started on his bad career. The family were communicants at the parish church, and efforts without end were made to turn the Kid from his career of wicked folly. His two sisters labored faithfully with him, but without avail. When the Kid came back from the Island to find his mother dead, he did not know his oldest sister. Grief had turned her pretty brown hair a snowy white.

He found his girl a little the worse for rum and late hours than when he left her, but he “took up” with her again. He was loyal at least. This time he tried, too, to be honest. His mother’s death had shocked him to the point where his “nerve” gave out. His brother gave him charge of one of his saloons and the Kid was “at work” keeping bar, with the way to respectability, as it goes on the East Side, open to him, when one of his old pals, who had found him out, turned up with a demand for money. He was a burglar and wanted a hundred dollars to “do up a job” in the country. The Kid refused, and his brother came in during the quarrel that ensued, flew into a rage, and grabbing the thief by the collar, threw him into the street. He went his way shaking his fist and threatening vengeance on both.

It was not long in coming. A jewelry store in Bridgeport was robbed and two burglars were arrested. One of them was the man “Jim” McDuff had thrown out of his saloon. He turned State’s evidence and swore that the Kid was in the job too. He was arrested and held in bail of ten thousand dollars. The Kid always maintained that he was innocent. His family believed him, but his past was against him. It was said, too, that back of the arrest was political persecution. His brother the saloon-keeper, who mixed politics with his beer, was the under dog just then in the fight in his ward. The situation was discussed from a practical standpoint in the McDuff household, and it ended with the Kid going up to Bridgeport and pleading guilty to theft to escape the worse charge of burglary. He was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment. That was how he got into “the pen.”

Annie, after he had been put in jail, went to the dogs on her own account rather faster than when they made a team. For a time she frequented the saloons of the Tenth Ward. When she crossed the Bowery at last she was nearing the end. For a year or two she frequented the disreputable houses in Elizabeth and Hester Streets. She was supposed to have a room in Downing Street, but it was the rarest of all events that she was there.

Two weeks before this morning, Fay Leslie, the girl who sat there telling me her story, met her on the Bowery with a cut and bruised face. She had been beaten in a fight in a Pell Street saloon with Flossie Lowell, one of the habitues of Chinatown. Fay took her to Bellevue Hospital, where she “had a pull with the night watch,” she told me, and she was kept there three or four days. When she came out she drifted back to Pell Street and took to drinking again. But she was a sick girl.

The night before she was with Fay in the saloon on the corner, when she complained that she did not feel well. She sat down in a chair and put her feet on another. In that posture she was found dead a little later, when her friend went to see how she was getting on.

“Rum killed her, I suppose,” I said, when Fay had ended her story.

“Yes! I suppose it did.”

“And you,” I ventured, “some day it will kill you too, if you do not look out.”

The girl laughed a loud and coarse laugh.

“Me?” she said, “not by a jugful. I’ve been soaking it fifteen years and I am alive yet.”

The dead girl sat there yet, with the cold, staring eyes, when I went my way. Outside the drinking went on with vile oaths. The dead wagon had been sent for, but it had other errands, and had not yet come around to Pell Street.

Thus ended the story of Kid McDuff’s girl.

CHAPTER VI.

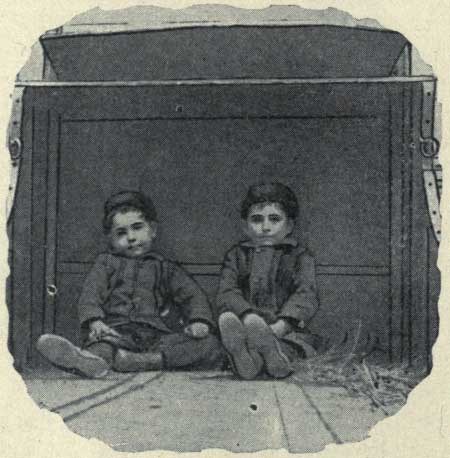

THE LITTLE TOILERS

POVERTY and child-labor are yoke-fellows everywhere. Their union is perpetual, indissoluble. The one begets the other. Need sets the child to work when it should have been at school and its labor breeds low wages, thus increasing the need. Solomon said it three thousand years ago, and it has not been said better since: “The destruction of the poor is their poverty.”

It is the business of the State to see to it that its interest in the child as a future citizen is not imperilled by the compact. Here in New York we set about this within the memory of the youngest of us. To-day we have compulsory education and a factory law prohibiting the employment of young children. All between eight and fourteen years old must go to school at least fourteen weeks in each year. None may labor in factories under the age of fourteen; not under sixteen unless able to read and write simple sentences in English. These are the barriers thrown up against the inroads of ignorance, poverty’s threat. They are barriers of paper. We have the laws, but we do not enforce them.

By that I do not mean to say that we make no attempt to enforce them. We do. We catch a few hundred truants each year and send them to reformatories to herd with thieves and vagabonds worse than they, rather illogically, since there is no pretence that there would have been room for them in the schools had they wanted to go there. We set half a dozen factory inspectors to canvass more than twice as many thousand workshops and to catechise the children they find there. Some are turned out and go back the next day to that or some other shop. The great mass that are under age lie and stay. And their lies go on record as evidence that we are advancing, and that child-labor is getting to be a thing of the past. That the horrible cruelty of a former day is; that the children have better treatment and a better time of it in the shops—often a good enough time to make one feel that they are better off there learning habits of industry than running about the streets, so long as there is no way of making them attend school—I believe from what I have seen. That the law has had the effect of greatly diminishing the number of child-workers I do not believe. It has had another and worse effect. It has bred wholesale perjury among them and their parents. Already they have become so used to it that it is a matter of sport and a standing joke among them. The child of eleven at home and at night-school is fifteen in the factory as a matter of course. Nobody is deceived, but the perjury defeats the purpose of the law.

More than a year ago, in an effort to get at the truth of the matter of children’s labor, I submitted to the Board of Health, after consultation with Dr. Felix Adler, who earned the lasting gratitude of the community by his labors on the Tenement House Commission, certain questions to be asked concerning the children by the sanitary police, then about to begin a general census of the tenements. The result was a surprise, and not least to the health officers. In the entire mass of nearly a million and a quarter of tenants8 only two hundred and forty-nine children under fourteen years of age were found at work in living-rooms. To anyone acquainted with the ordinary aspect of tenement-house life the statement seemed preposterous, and there are valid reasons for believing that the policemen missed rather more than they found even of those that were confessedly or too evidently under age. They were seeking that which, when found, would furnish proof of law-breaking against the parent or employer, a fact of which these were fully aware. Hence their coming uniformed and in search of children into a house could scarcely fail to give those a holiday who were not big enough to be palmed off as fourteen at least. Nevertheless, upon reflection, it seemed probable that the policemen were nearer the truth than their critics. Their census took no account of the factory in the back yard, but only of the living rooms, and it was made during the day. Most of the little slaves, as of those older in years, were found in the sweater’s district on the East Side, where the home work often only fairly begins after the factory has shut down for the day and the stores released their army of child-laborers. Had the policemen gone their rounds after dark they would have found a different state of things. Between the sweat-shops and the school, which, as I have shown, is made to reach farther down among the poorest in this Jewish quarter than anywhere else in this city, the children were fairly accounted for in the daytime. The record of school attendance in the district shows that forty-seven attended day-school for every one who went to night-school.

To settle the matter to my own satisfaction I undertook a census of a number of the most crowded houses, in company with a policeman not in uniform. The outcome proved that, as regards those houses at least, it was as I suspected, and I have no doubt they were a fair sample of the rest. In nine tenements that were filled with home-workers we found five children at work who owned that they were under fourteen. Two were girls nine years of age. Two boys said they were thirteen. We found thirteen who swore that they were of age, proof which the policeman as an uninterested census-taker would have respected as a matter of course, even though he believed with me that the children lied. On the other hand, in seven back-yard factories we found a total of 63 children, of whom 5 admitted being under age, while of the rest 45 seemed surely so. To the other 13 we gave the benefit of the doubt, but I do not think they deserved it. All the 63 were to my mind certainly under fourteen, judging not only from their size, but from the whole appearance of the children. My subsequent experience confirmed me fully in this belief. Most of them were able to write their names after a fashion. Few spoke English, but that might have been a subterfuge. One of the home-workers, a marvellously small lad whose arms were black to the shoulder from the dye in the cloth he was sewing, and who said in his broken German, without evincing special interest in the matter, that he had gone to school “e’ bische’,” referred us to his “mother” for a statement as to his age. The “mother,” who proved to be the boss’s wife, held a brief consultation with her husband and then came forward with a verdict of sixteen. When we laughed rather incredulously the man offered to prove by his marriage certificate that the boy must be sixteen. The effect of this demonstration was rather marred, however, by the inopportune appearance of another tailor, who, ignorant of the crisis, claimed the boy as his. The situation was dramatic. The tailor with the certificate simply shrugged his shoulders and returned to his work, leaving the boy to his fate.

One girl, who could not have been twelve years old, was hard at work at a sewing-machine in a Division Street shirt factory when we came in. She got up and ran the moment she saw us, but we caught her in the next room hiding behind a pile of shirts. She said at once that she was fourteen years old but didn’t work there. She “just came in.” The boss of the shop was lost in astonishment at seeing her when we brought her back. He could not account at all for her presence. There were three boys at work in the room who said “sixteen” without waiting to be asked. Not one of them was fourteen. The habit of saying fourteen or sixteen—the fashion varies with the shops and with the degree of the child’s educational acquirements—soon becomes an unconscious one with the boy. He plumps it out without knowing it. While occupied with these investigations I once had my boots blacked by a little shaver, hardly knee-high, on a North River ferry-boat. While he was shining away, I suddenly asked him how old he was. “Fourteen, sir!” he replied promptly, without looking up.

In a Hester Street house we found two little girls pulling basting-thread. They were both Italians and said that they were nine. In the room in which one of them worked thirteen men and two women were sewing. The child could speak English. She said that she was earning a dollar a week and worked every day from seven in the morning till eight in the evening. This sweat-shop was one of the kind that comes under the ban of the new law, passed last winter—that is, if the factory inspector ever finds it. Where the crowds are greatest and the pay poorest, the Italian laborer’s wife and child have found their way in since the strikes among the sweater’s Jewish slaves, outbidding even these in the fierce strife for bread.

Even the crowding, the feverish haste of the half-naked men and women, and the litter and filth in which they worked, were preferable to the silence and desolation we encountered in one shop up under the roof of a Broome Street tenement. The work there had given out—there had been none these two months, said the gaunt, hard-faced woman who sat eating a crust of dry bread and drinking water from a tin pail at the empty bench. The man sat silent and moody in a corner; he was sick. The room was bare. The only machine left was not worth taking to the pawnshop. Two dirty children, naked but for a torn undershirt apiece, were fishing over the stair-rail with a bent pin on an idle thread. An old rag was their bait.

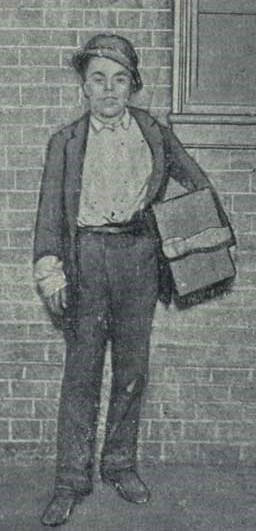

From among a hundred and forty hands on two big lofts in a Suffolk Street factory we picked seventeen boys and ten girls who were patently under fourteen years of age, but who all had certificates, sworn to by their parents, to the effect that they were sixteen. One of them whom we judged to be between nine and ten, and whose teeth confirmed our diagnosis—the second bicuspids in the lower jaw were just coming out—said that he had worked there “by the year.” The boss, deeming his case hopeless, explained that he only “made sleeves and went for beer.” Two of the smallest girls represented themselves as sisters, respectively sixteen and seventeen, but when we came to inquire which was the oldest, it turned out that she was the sixteen-year one. Several boys scooted as we came up the stairs. When stopped they claimed to be visitors. I was told that this sweater had been arrested once by the Factory Inspector, but had successfully barricaded himself behind his pile of certificates. I caught the children laughing and making faces at us behind our backs as often as these were brought out anywhere. In an Attorney Street “pants” factory we counted thirteen boys and girls who could not have been of age, and on a top floor in Ludlow Street, among others, two brothers, sewing coats, who said that they were thirteen and fourteen, but, when told to stand up, looked so ridiculously small as to make even their employer laugh. Neither could read, but the oldest could sign his name and did it thus, from right to left:

It was the full extent of his learning, and all he would probably ever receive.

He was one of many Jewish children we came across who could neither read nor write. Most of them answered that they had never gone to school. They were mostly those of larger growth, bordering on fourteen, whom the charity school managers find it next to impossible to reach, the children of the poorest and most ignorant immigrants, whose work is imperatively needed to make both ends meet at home, the “thousand” the school census failed to account for. To banish them from the shop serves no useful purpose. They are back the next day, if not sooner. One of the Factory Inspectors told me of how recently he found a little boy in a sweat-shop and sent him home. He went up through the house after that and stayed up there quite an hour. On his return it occurred to him to look in to see if the boy was gone. He was back and hard at work, and with him were two other boys of his age who, though they claimed to have come in with dinner for some of the hands, were evidently workers there.

So much for the sweat-shops. Jewish, Italian, and Bohemian, the story is the same always. In the children that are growing up, to “vote as would their master’s dogs if allowed the right of suffrage,” the community reaps its reward in due season for allowing such things to exist. It is a kind of interest in the payment of which there is never default. The physician gets another view of it. “Not long ago,” says Dr. Annie S. Daniel, in the last report of the out-practice of the Infirmary for Women and Children, “we found in such an apartment five persons making cigars, including the mother. Two children were ill with diphtheria. Both parents attended to the children; they would syringe the nose of each child and, without washing their hands, return to their cigars. We have repeatedly observed the same thing when the work was manufacturing clothing and under-garments, to be bought as well by the rich as the poor. Hand-sewed shoes, made for a fashionable Broadway shoe store, were sewed at home by a man in whose family were three children with scarlet fever. And such instances are common. Only death or lack of work closes tenement-house manufactories. When reported to the Board of Health, the inspector at once prohibits further manufacture during the continuance of the disease, but his back is scarcely turned before the people return to their work. When we consider that stopping this work means no food and no roof over their heads, the fact that the disease may be carried by their work cannot be expected to impress the people.”

SHINE, SIR?

And she adds: “Wages have steadily decreased. Among the women who earned the whole or part of the income the finishing of pantaloons was the most common occupation. For this work in 1881 they received ten to fifteen cents per pair; for the same work in 1891 three to five, at the most ten cents per pair. When the women have paid the express charges to and from the factory there is little margin left for profit. The women doing this work claim that wages are reduced because of the influx of Italian women.” The rent has not fallen, however, and the need of every member of the family contributing by his or her work to its keep is greater than ever. The average total wages of 160 families whom the doctor personally treated and interrogated during the year was $5.99 per week, while the average rent was $8.62¾. The list included twenty-three different occupations and trades. The maximum wages was $19, earned by three persons in one family; the minimum $1.50, by a woman finishing pantaloons and living in one room for which she paid $4 a month rent! In nearly every instance observed by Dr. Daniel, the children’s wages, when there were working children, was the greater share of the family income. A specimen instance is that of a woman with a consumptive husband, who is under her treatment. The wife washes and goes out by the day, when she can get such work to do. The three children, aged eleven, seven, and five years, not counting the baby for a wonder, work at home covering wooden buttons with silk at four cents a gross. The oldest goes to school, but works with the rest evenings and on Saturday and Sunday, when the mother does the finishing. Their combined earnings are from $3 to $6 a week, the children earning two-thirds. The rent is $8 a month.