полная версия

полная версияThe Children of the Poor

It struck me then, and it has seemed to me since, that this man’s position to the problem was most comprehensive. The evidence of his long-range view was convincing. Society had indeed arrived at the same diagnosis some time before. Reasoning by exclusion, as doctors do in doubtful diseases, the symptoms of which are clearer than their cause, it had conjectured that if the “tough” whom it must maintain in idleness behind prison-bars, to keep him from preying upon it, was a creature of environment, not justly to blame, the community must be, for allowing him to grow up a “tough.” So, in self-defence, it had turned its hand to the forming of character in proportion as it had come to own its failure to reform it. To that failure the trench in the Potter’s Field bore unceasing witness. Its claim to be heard in evidence was incontestable.

Now that it has been heard, its testimony confirms the judgment that had already experience to back it. There is no longer room for doubt that with the children lies the solution of the problem of poverty, as far as it can be reached under existing forms of society and with our machinery for securing justice by government. The wisdom of generations that were dust two thousand years ago made this choice. We have been long in making it, but not too long if our travail has made it clear at last that for all time to come it must be the only safe choice. And this, whether from the standpoint of the Christian or the unbeliever, from that of humanity or mere business. If the matter is reduced to a simple sum in arithmetic, so much for so much—child-rescue, as the one way of balancing waste with gain, loss with profit, becomes the imperative duty of society, its chief bulwark against bankruptcy and wreck.

Thus, through the gloom of the Potter’s Field that has levied such heavy tribute on our city in the past—even the tenth of its life—brighter skies, a new hope, are discerned beyond. They brighten even the slum tenement, and shine into the home which just now we despaired of reaching by any other road than that of pulling it down. Tireless, indeed, the hands need be that have taken up this task. Flag their efforts ever so little, hard-won ground is lost, mischief done. But we are gaining, no longer losing, ground. Seen from the tenement, through the frame-work of injustice and greed that cursed us with it, the outlook seemed little less than despairing. Groping vainly, with unseeing eyes, we said: There is no way out. The children, upon whom the curse of the tenement lay heaviest, have found it for us. Truly it was said: “A little child shall lead them.”

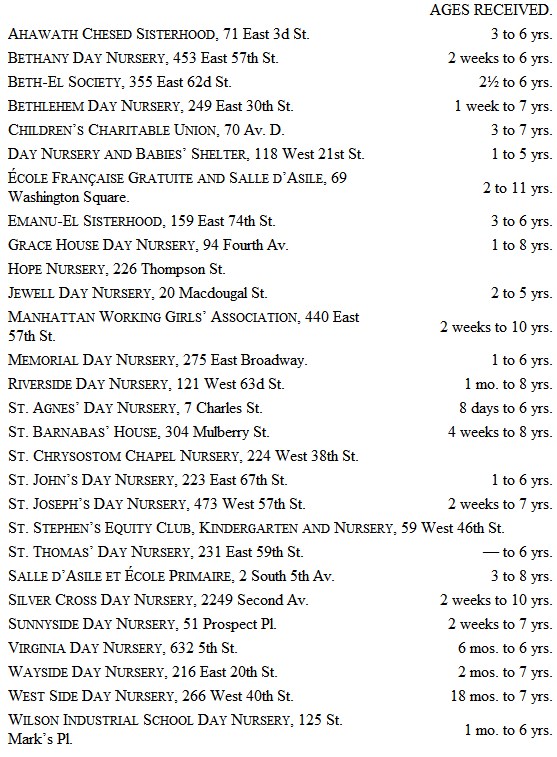

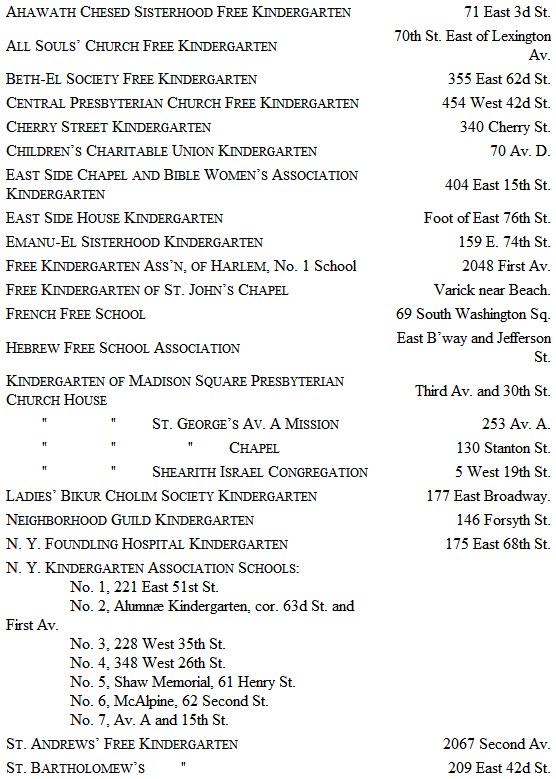

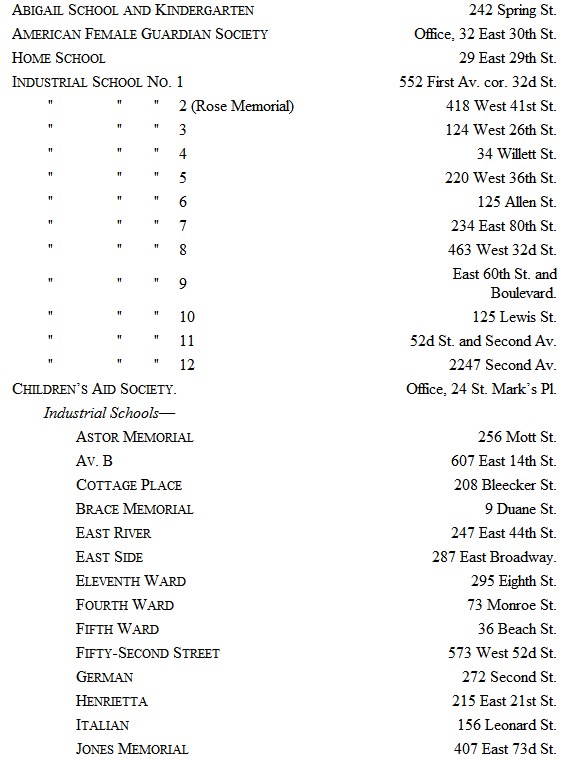

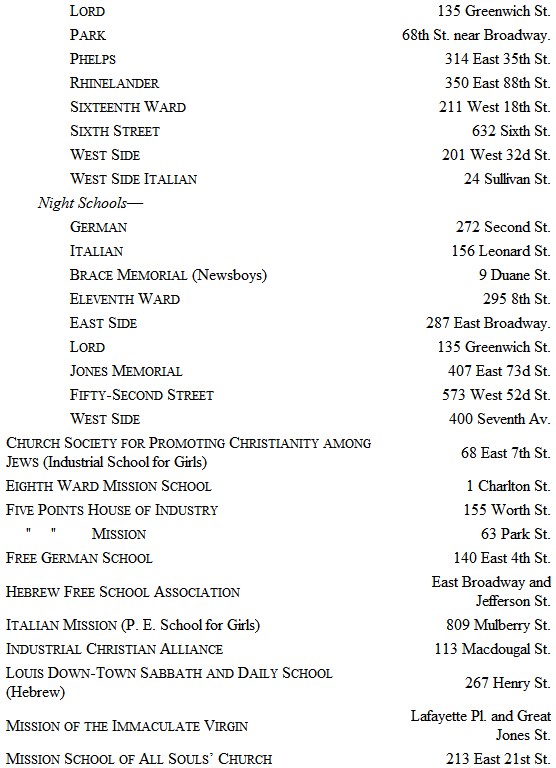

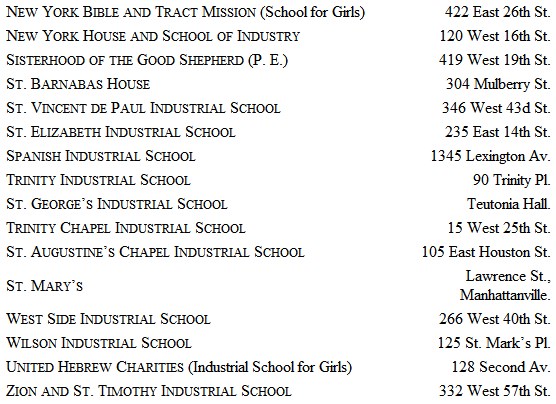

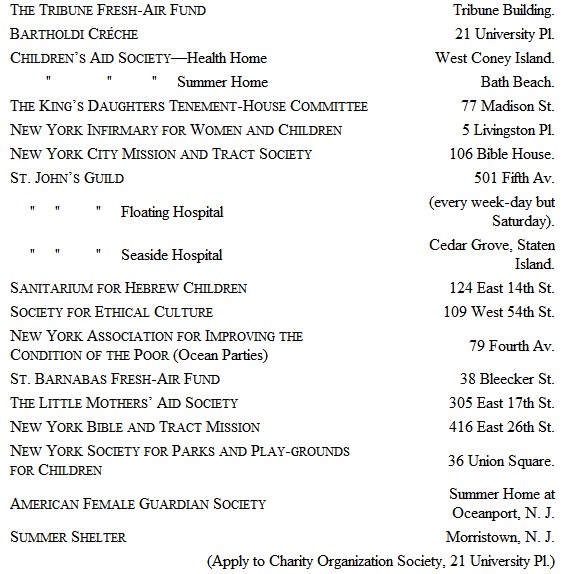

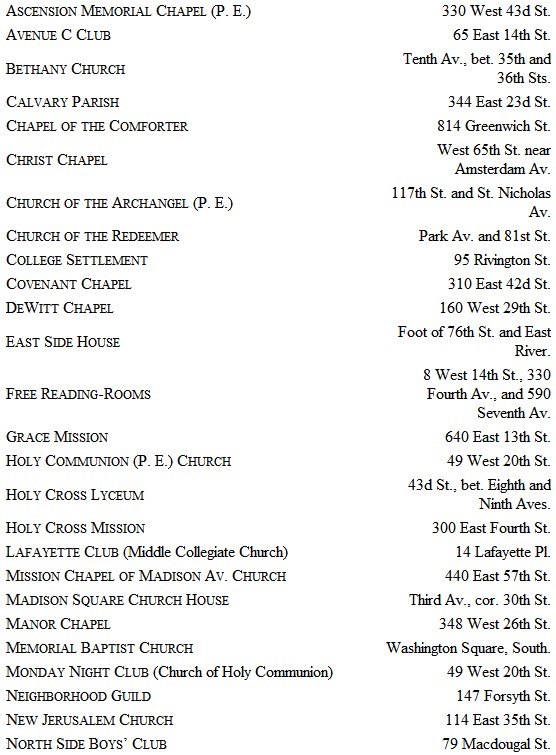

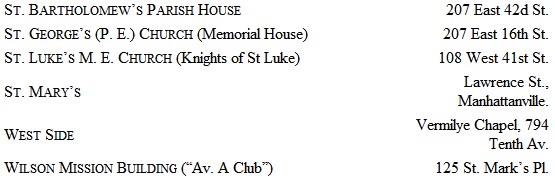

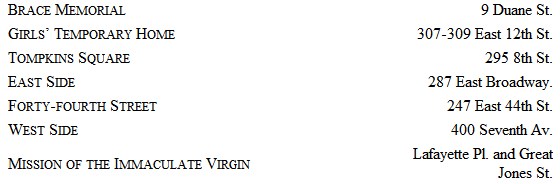

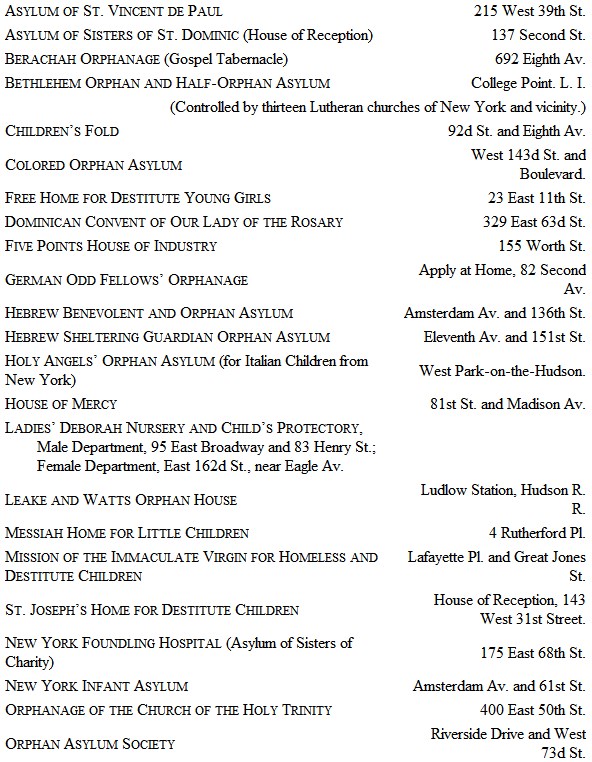

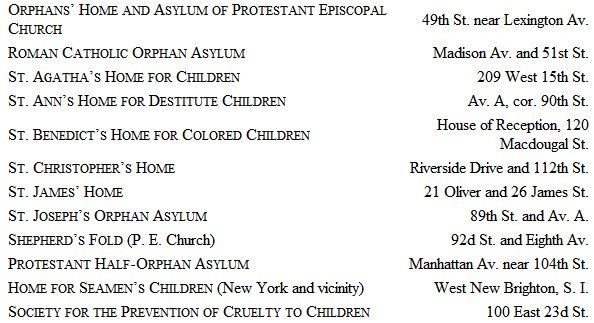

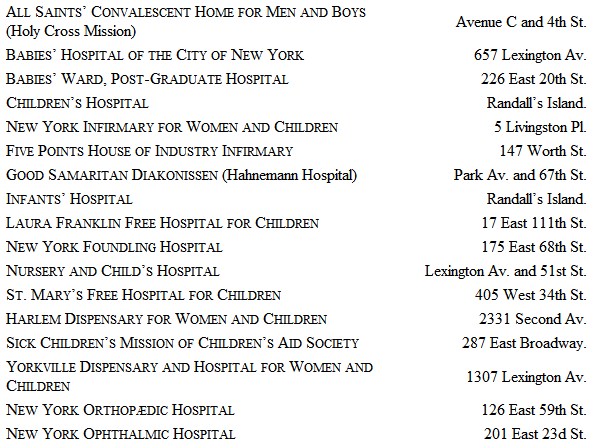

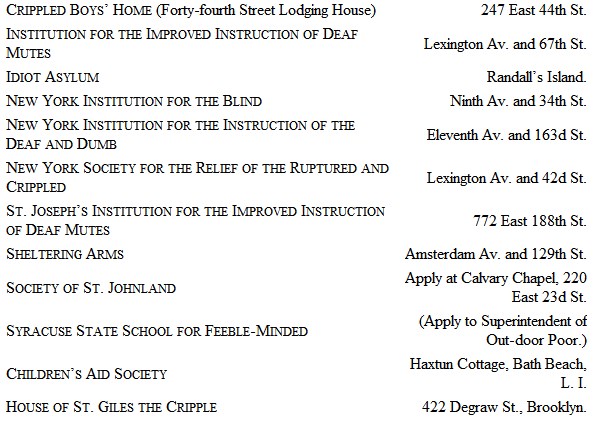

REGISTER OF CHILDREN’S CHARITIES

AS PUBLISHED BY THE CHARITY ORGANIZATION SOCIETY

In addition to the charities given here, seventy-eight churches of all denominations conduct weekly industrial and sewing classes, generally on Saturdays, for which see the Directory of the Charity Organization Society, under Churches, where may also be found the register of thirty-two fresh-air funds not recorded below, and of some kindergartens and clubs established by various churches for the children of their congregations.

NURSERIES.

KINDERGARTENS.

INDUSTRIAL SCHOOLS.

FRESH AIR WORK.

BOYS’ CLUBS AND READING-ROOMS.

CHILDREN’S LODGING-HOUSES.

CHILDREN’S LODGING-HOUSES.

CHILDREN’S HOMES—TEMPORARY AND PERMANENT.

REFORMATORY INSTITUTIONS.

CHILDREN’S HOSPITALS AND DISPENSARIES.

ASYLUMS FOR DEFECTIVE CHILDREN.

1

It is, nevertheless, true that while immigration peoples our slums, it also keeps them from stagnation. The working of the strong instinct to better themselves, that brought the crowds here, forces layer after layer of this population up to make room for the new crowds coming in at the bottom, and thus a circulation is kept up that does more than any sanitary law to render the slums harmless. Even the useless sediment is kept from rotting by being constantly stirred.

2

Report of committing magistrates. See Annual Report of Children’s Aid Society, 1891.

3

The census referred to in this chapter was taken for a special purpose, by a committee of prominent Hebrews, in August, 1890, and was very searching.

4

Dr. Roger S. Tracy’s report of the vital statistics for 1891 shows that, while the general death-rate of the city was 25.96 per 1,000 of the population—that of adults (over five years) 17.13, and the baby death-rate (under five years) 93.21—in the Italian settlement in the west half of the Fourteenth Ward the record stood as follows: general death-rate, 33.52; adult death-rate, 16.29; and baby death-rate, 150.52. In the Italian section of the Fourth Ward it stood: general death-rate, 34.88; adult death-rate, 21.29; baby death-rate 119.02. In the sweaters district in the lower part of the Tenth Ward the general death rate was 16.23; the adult death rate, 7.59; and the baby death rate 61.15. Dr. Tracy adds: “The death-rate from phthisis was highest in houses entirely occupied by cigarmakers (Bohemians), and lowest in those entirely occupied by tailors. On the other hand, the death-rates from diphtheria and croup and measles were highest in houses entirely occupied by tailors.”

5

Meaning “teachers.”

6

Even as I am writing a transformation is being worked in some of the filthiest streets on the East Side by a combination of new asphalt pavements with a greatly improved street cleaning service that promises great things. Some of the worst streets have within a few weeks become as clean as I have not seen them in twenty years, and as they probably never were since they were made. The unwonted brightness of the surroundings is already visibly reflected in the persons and dress of the tenants, notably the children. They take to it gladly, giving the lie to the old assertion that they are pigs and would rather live like pigs.

7

As a matter of fact, I heard, after the last one that caused so much discussion, in a court that sent seventy-five children to the show, a universal growl of discontent. The effect on the children, even to those who received presents, was bad. They felt that they had been on exhibition, and their greed was aroused. It was as I expected it would be.

8

The Sanitary census of 1891 gave 37,358 tenements, containing 276,565 families, including 160,708 children under five years of age; total population of tenements, 1,225,411.

9

The general impression survives with me that the children’s teeth were bad, and those of the native born the worst. Ignorance and neglect were clearly to blame for most of it, poor and bad food for the rest, I suppose. I give it as a layman’s opinion, and leave it to the dentist to account for the bad teeth of the many who are not poor. That is his business.

10

The fourteenth year is included. The census phrase means “up to 15.”

11

The average attendance was only 136,413, so that there were 60,000 who were taught only a small part of the time.

12

See Minutes of Stated Session of the Board of Education, February 8, 1892.

13

Meaning evidently in this case “up to fourteen.”

14

Report of New York Catholic Protectory, 1892.

15

If this were not the sober statement of public officials of high repute it would seem fairly incredible.

16

Between 1880 and 1890 the increase in assessed value of the real and personal property in this city was 48.36 per cent., while the population increased 41.06 per cent.

17

Philosophy of Crime and Punishment, by Dr. William T. Harris, Federal Commissioner of Education.

18

Seventeenth Annual Report of Society, 1892.

19

English Social Movements, by Robert Archey Woods, page 196.

20

The Superintendent of the House of Refuge for thirty years wrote recently: “It is essential to have the plays of the children more carefully watched than their work.”

21

Report for 1891 of Children’s Aid Society.

22

In this reckoning is included employment found for many big boys and girls, who were taken as help, and were thus given the chance which the city denied them.

23

It is inevitable, of course, that such a programme should steer clear of the sectarian snags that lie plentifully scattered about. I have a Roman Catholic paper before me in which the Society’s “villainous work, which consists chiefly in robbing the Catholic child of his faith,” is hotly denounced in an address to the Archbishop of New York. Mr. Brace’s policy was to meet such attacks with silence, and persevere in his work. The Society still follows his plan. Catholic or Protestant—the question is never raised. “No Catholic child,” said one of its managers once to me, “is ever brought to us. A poor child is brought and we care for it.”

24

The Society pleads for a farm of its own, close to the city, where it can organize a “farm school” for the older boys. There they could be taken on probation and their fitness for the West be ascertained. They would be more useful to the farmers and some trouble would be avoided. Two farms, or three, to get as near to the family plan as possible, would be better. The Children’s Aid Society of Boston has three farm schools, and its work is very successful.

25

I once questioned a class of 71 boys between eight and twelve years old in a reform school, with this result: 22 said they blacked boots; 36 sold papers; 26 did both; 40 “slept out;” but only 3 of them all were fatherless, 11 motherless, showing that they slept out by choice. The father probably had something to do with it most of the time. Three-fourths of the lads stood up when I asked them if they had been to Central Park. The teacher asked one of those who did not rise, a little shaver, if he had never been in the Park. “No, mem!” he replied, “me father he went that time.”

26

The lodging-houses are following a noteworthy precedent. From the Society for the Prevention of Pauperism, organized in the beginning of this century, sprang the first savings bank in the country.

27

That is the average number constantly in asylums. With those that come and go, it foots up quite 25,000 children a year that are a public charge.

28

Report upon the Care of Dependent Children in New York City and elsewhere, to the State Board of Charities, by Commissioner Josephine Shaw Lowell. December, 1889.

29

Mrs. Josephine Shaw Lowell on Dependent Children. Report of 1889.

30

Anna T. Wilson: Some Arguments for the Boarding-out of Dependent Children in the State of New York. This opposition the Superintendent explains in his report for 1891, to be due in part to the lying stories about abuse in the West, told by bad boys who return to the city. He adds, however, that “oftentimes the most strenuous opposition … is made by step-mothers, uncles, aunts, and cousins,” and is “due in the majority of cases not to any special interest in the child’s welfare, but to self-interest, the relative wishing to obtain a situation for the boy in order to get his weekly wages.”

31

It will do so hereafter. This autumn the discovery was made that the city was asked to pay for more children than there ought to be in the institutions according to the record of commitments. The comptroller sent two of his clerks to count all the children. The result was to show slipshod book-keeping, if nothing worse, in certain cases. Hereafter the ceremony of counting the children will be gone through every six months. Nothing could more clearly show the irresponsible character of the whole business and the need of a change, lest we drift into corporate pauperism in addition to encouraging the vice in the individual.

32

In 1854, with a population of 605,000, there were 6,657 licensed and unlicensed saloons in the city, or 1 to every 90.8 of its inhabitants. At the beginning of 1892, with a population of 1,706,500, there were 7,218 saloons, or 1 to every 236.42. Counting all places where liquor was sold by license, including hotels, groceries, steamboats, etc., the number was 9,050, or 1 to every 188.56 inhabitants.