полная версия

полная версияThe Children of the Poor

In the evening classes the girls of “fourteen” flourished, as everywhere in Jewtown. There were many who were much older, and some who were a long way yet from that safe goal. One sober-faced little girl, who wore a medal for faithful attendance and who could not have been much over ten, if as old as that, said that she “went out dressmaking” and so helped her mother. Another, who was even smaller and had been here just three weeks, yet understood what was said to her, explained in broken German that she was learning to work at “Blumen” in a Grand Street shop, and would soon be able to earn wages that would help support the family of four children, of whom she was the oldest. The girl who sat in the seat with her was from a Hester Street tenement. Her clothes showed that she was very poor. She read very fluently on demand a story about a big dog that tried to run away, or something, “when he had a chance.” When she came to translate what she had read into German, which many of the Russian children understand, she got along until she reached the word “chance.” There she stopped, bewildered. It was the one idea of which her brief life had no embodiment, the thing it had altogether missed.

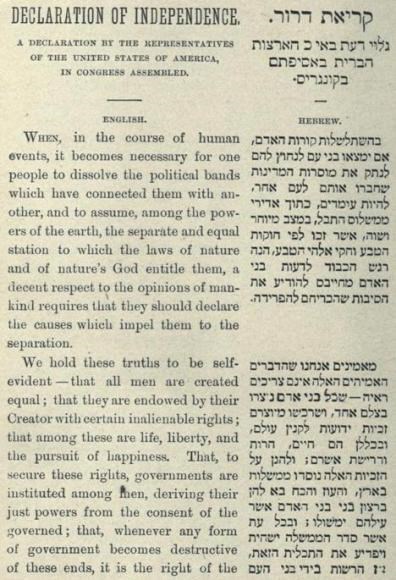

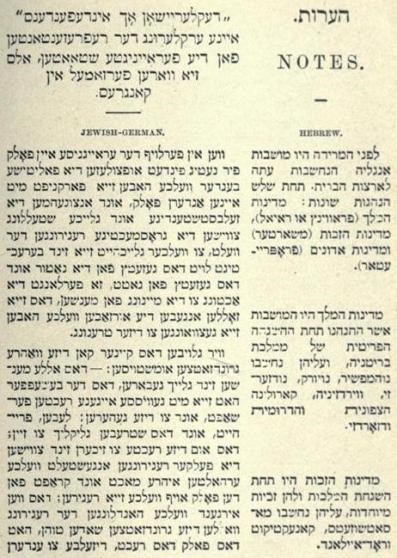

The Declaration of Independence half the children knew by heart before they had gone over it twice. To help them along it is printed in the school-books with a Hebrew translation and another in Jargon, a “Jewish-German,” in parallel columns and the explanatory notes in Hebrew. The Constitution of the United States is treated in the same manner, but it is too hard, or too wearisome, for the children. They “hate” it, says the teacher, while the Declaration of Independence takes their fancy at sight. They understand it in their own practical way, and the spirit of the immortal document suffers no loss from the annotations of Ludlow Street, if its dignity is sometimes slightly rumpled.

“When,” said the teacher to one of the pupils, a little working-girl from an Essex Street sweater’s shop, “the Americans could no longer put up with the abuse of the English who governed the colonies, what occurred then?”

“A strike!” responded the girl, promptly. She had found it here on coming and evidently thought it a national institution upon which the whole scheme of our government was founded.

It was curious to find the low voices of the children, particularly the girls, an impediment to instruction in this school. They could sometimes hardly be heard for the noise in the street, when the heat made it necessary to have the windows open. But shrillness is not characteristic even of the Pig-market when it is noisiest and most crowded. Some of the children had sweet singing voices. One especially, a boy with straight red hair and a freckled face, chanted in a plaintive minor key the One Hundred and Thirtieth Psalm, “Out of the depths” etc., and the harsh gutturals of the Hebrew became sweet harmony until the sad strain brought tears to our eyes.

The dirt of Ludlow Street is all-pervading and the children do not escape it. Rather, it seems to have a special affinity for them, or they for the dirt. The duty of imparting the fundamental lesson of cleanliness devolves upon a special school officer, a matron, who makes the round of the classes every morning with her alphabet: a cake of soap, a sponge, and a pitcher of water, and picks out those who need to be washed. One little fellow expressed his disapproval of this programme in the first English composition he wrote, as follows:

Despite this hint, the lesson is enforced upon the children, but there is no evidence that it bears fruit in their homes to any noticeable extent, as is the case with the Italians I spoke of. The homes are too hopeless, the grind too unceasing. The managers know it and have little hope of the older immigrants. It is toward getting hold of their children that they bend every effort, and with a success that shows how easily these children can be moulded for good or for bad. Nor do they let go their grasp of them until the job is finished. The United Hebrew Charities maintain trade-schools for those who show aptness for such work, and a very creditable showing they make. The public school receives all those who graduate from what might be called the American primary in East Broadway.

The smoky torches on many hucksters’ carts threw their uncertain yellow light over Hester Street as I watched the children troop homeward from school one night. Eight little pedlers hawking their wares had stopped under the lamp on the corner to bargain with each other for want of cash customers. They were engaged in a desperate but vain attempt to cheat one of their number who was deaf and dumb. I bought a quire of note-paper of the mute for a cent and instantly the whole crew beset me in a fierce rivalry, to which I put a hasty end by buying out the little mute’s poor stock—ten cents covered it all—and after he had counted out the quires, gave it back to him. At this act of unheard-of generosity the seven, who had remained to witness the transfer, stood speechless. As I went my way, with a sudden common impulse they kissed their hands at me, all rivalry forgotten in their admiration, and kept kissing, bowing, and salaaming until I was out of sight. “Not bad children,” I mused as I went along, “good stuff in them, whatever their faults.” I thought of the poor boy’s stock, of the cheapness of it, and then it occurred to me that he had charged me just twice as much for the paper I gave him back as for the penny quire I bought. But when I went back to give him a piece of my mind the boys were gone.

CHAPTER IV.

TONY AND HIS TRIBE

I HAVE a little friend somewhere in Mott Street whose picture comes up before me. I wish I could show it to the reader, but to photograph Tony is one of the unattained ambitions of my life. He is one of the whimsical birds one sees when he hasn’t got a gun, and then never long enough in one place to give one a chance to get it. A ragged coat three sizes at least too large for the boy, though it has evidently been cropped to meet his case, hitched by its one button across a bare brown breast; one sleeve patched on the under side with a piece of sole-leather that sticks out straight, refusing to be reconciled; trousers that boasted a seat once, but probably not while Tony has worn them; two left boots tied on with packing twine, bare legs in them the color of the leather, heel and toe showing through; a shock of sunburnt hair struggling through the rent in the old straw hat; two frank, laughing eyes under its broken brim—that is Tony.

He stood over the gutter the day I met him, reaching for a handful of mud with which to “paste” another hoodlum who was shouting defiance from across the street. He did not see me, and when my hand touched his shoulder his whole little body shrank with a convulsive shudder, as from an expected blow. Quick as a flash he dodged, and turning, out of reach, confronted the unknown enemy, gripping tight his handful of mud. I had a bunch of white pinks which a young lady had given me half an hour before for one of my little friends. “They are yours,” I said, and held them out to him, “take them.”

Doubt, delight, and utter bewilderment struggled in the boy’s face. He said not one word, but when he had brought his mind to believe that it really was so, clutched the flowers with one eager, grimy fist, held them close against his bare breast, and, shielding them with the other, ran as fast as his legs could carry him down the street. Not far; fifty feet away he stopped short, looked back, hesitated a moment, then turned on his track as fast as he had come. He brought up directly in front of me, a picture a painter would have loved, ragamuffin that he was, with the flowers held so tightly against his brown skin, scraped out with one foot and made one of the funniest little bows.

“Thank you,” he said. Then he was off. Down the street I saw squads of children like himself running out to meet him. He darted past and through them all, never stopping, but pointing back my way, and in a minute there bore down upon me a crowd of little ones, running breathless with desperate entreaty: “Oh, mister! give me a flower.” Hot tears of grief and envy—human passions are much the same in rags and in silks—fell when they saw I had no more. But by that time Tony was safe.

And where did he run so fast? For whom did he shield the “posy” so eagerly, so faithfully, that ragged little wretch that was all mud and patches? I found out afterward when I met him giving his sister a ride in a dismantled tomato-crate, likely enough “hooked” at the grocer’s. It was for his mother. In the dark hovel he called home, to the level of which all it sheltered had long since sunk through the brutal indifference of a drunken father, my lady’s pinks blossomed, and, long after they were withered and yellow, still stood in their cracked jar, visible token of something that had entered Tony’s life and tenement with sweetening touch that day for the first time. Alas! for the last, too, perhaps. I saw Tony off and on for a while and then he was as suddenly lost as he was found, with all that belonged to him. Moved away—put out, probably—and, except the assurance that they were still somewhere in Mott Street, even the saloon could give me no clue to them.

I gained Tony’s confidence, almost, in the time I knew him. There was a little misunderstanding between us that had still left a trace of embarrassment when Tony disappeared. It was when I asked him one day, while we were not yet “solid,” if he ever went to school. He said “sometimes,” and backed off. I am afraid Tony lied that time. The evidence was against him. It was different with little Katie, my nine-year-old housekeeper of the sober look. Her I met in the Fifty-second Street Industrial School, where she picked up such crumbs of learning as were for her in the intervals of her housework. The serious responsibilities of life had come early to Katie. On the top floor of a tenement in West Forty-ninth Street she was keeping house for her older sister and two brothers, all of whom worked in the hammock factory, earning from $4.50 to $1.50 a week. They had moved together when their mother died and the father brought home another wife. Their combined income was something like $9.50 a week, and the simple furniture was bought on instalments. But it was all clean, if poor. Katie did the cleaning and the cooking of the plain kind. They did not run much to fancy cooking, I guess. She scrubbed and swept and went to school, all as a matter of course, and ran the house generally, with an occasional lift from the neighbors in the tenement, who were, if anything, poorer than they. The picture shows what a sober, patient, sturdy little thing she was, with that dull life wearing on her day by day. At the school they loved her for her quiet, gentle ways. She got right up when asked and stood for her picture without a question and without a smile.

“I SCRUBS.”—KATIE, WHO KEEPS HOUSE IN WEST FORTY-NINTH STREET.

“What kind of work do you do?” I asked, thinking to interest her while I made ready.

“I scrubs,” she replied, promptly, and her look guaranteed that what she scrubbed came out clean.

Katie was one of the little mothers whose work never ends. Very early the cross of her sex had been laid upon the little shoulders that bore it so stoutly. Tony’s, as likely as not, would never begin. There were ear-marks upon the boy that warranted the suspicion. They were the ear-marks of the street to which his care and education had been left. The only work of which it heartily approves is that done by other people. I came upon Tony once under circumstances that foreshadowed his career with tolerable distinctness. He was at the head of a gang of little shavers like himself, none over eight or nine, who were swaggering around in a ring, in the middle of the street, rigged out in war-paint and hen-feathers, shouting as they went: “Whoop! We are the Houston Streeters.” They meant no harm and they were not doing any just then. It was all in the future, but it was there, and no mistake. The game which they were then rehearsing was one in which the policeman who stood idly swinging his club on the corner would one day take a hand, and not always the winning one.

The fortunes of Tony and Katie, simple and soon told as they are, encompass as between the covers of a book the whole story of the children of the poor, the story of the bad their lives struggle vainly to conquer, and the story of the good that crops out in spite of it. Sickness, that always finds the poor unprepared and soon leaves them the choice of beggary or starvation, hard times, the death of the bread-winner, or the part played by the growler in the poverty of the home, may vary the theme for the elders; for the children it is the same sad story, with little variation, and that rarely of a kind to improve. Happily for their peace of mind, they are the least concerned about it. In New York, at least, the poor children are not the stunted repining lot we have heard of as being hatched in cities abroad. Stunted in body perhaps. It was said of Napoleon that he shortened the average stature of the Frenchman one inch by getting all the tall men killed in his wars. The tenement has done that for New York. Only the other day one of the best known clergymen in the city, who tries to attract the boys to his church on the East Side by a very practical interest in them, and succeeds admirably in doing it, told me that the drill-master of his cadet corps was in despair because he could barely find two or three among half a hundred lads verging on manhood, over five feet six inches high. It is queer what different ways there are of looking at a thing. My medical friend finds in the fact that poverty stunts the body what he is pleased to call a beautiful provision of nature to prevent unnecessary suffering: there is less for the poverty to pinch then. It is self-defence, he says, and he claims that the consensus of learned professional opinion is with him. Yet, when this shortened sufferer steals a loaf of bread to make the pinching bear less hard on what is left, he is called a thief, thrown into jail, and frowned upon by the community that just now saw in his case a beautiful illustration of the operation of natural laws for the defence of the man.

Stunted morally, yes! It could not well be otherwise. But stunted in spirits—never! As for repining, there is no such word in his vocabulary. He accepts life as it comes to him and gets out of it what he can. If that is not much, he is not justly to blame for not giving back more to the community of which by and by he will be a responsible member. The kind of the soil determines the quality of the crop. The tenement is his soil and it pervades and shapes his young life. It is the tenement that gives up the child to the street in tender years to find there the home it denied him. Its exorbitant rents rob him of the schooling that is his one chance to elude its grasp, by compelling his enrolment in the army of wage-earners before he has learned to read. Its alliance with the saloon guides his baby feet along the well-beaten track of the growler that completes his ruin. Its power to pervert and corrupt has always to be considered, its point of view always to be taken to get the perspective in dealing with the poor, or the cart will seem to be forever getting before the horse in a way not to be understood. We had a girl once at our house in the country who left us suddenly after a brief stay and went back to her old tenement life, because “all the green hurt her eyes so.” She meant just what she said, though she did not know herself what ailed her. It was the slum that had its fatal grip upon her. She longed for its noise, its bustle, and its crowds, and laid it all to the green grass and the trees that were new to her as steady company.

From this tenement the street offered, until the kindergarten came not long ago, the one escape, does yet for the great mass of children—a Hobson’s choice, for it is hard to say which is the most corrupting. The opportunities rampant in the one are a sad commentary on the sure defilement of the other. What could be expected of a standard of decency like this one, of a household of tenants who assured me that Mrs. M–, at that moment under arrest for half clubbing her husband to death, was “a very good, a very decent, woman indeed, and if she did get full, he (the husband) was not much.” Or of the rule of good conduct laid down by a young girl, found beaten and senseless in the street up in the Annexed District last autumn: “Them was two of the fellers from Frog Hollow,” she said, resentfully, when I asked who struck her; “them toughs don’t know how to behave theirselves when they see a lady in liquor.”

Hers was the standard of the street, the other’s that of the tenement. Together they stamp the child’s life with the vicious touch which is sometimes only the caricature of the virtues of a better soil. Under the rough burr lie undeveloped qualities of good and of usefulness, rather, perhaps, of the capacity for them, that crop out in constant exhibitions of loyalty, of gratitude, and true-heartedness, a never-ending source of encouragement and delight to those who have made their cause their own and have in their true sympathy the key to the best that is in the children. The testimony of a teacher for twenty-five years in one of the ragged schools, who has seen the shanty neighborhood that surrounded her at the start give place to mile-long rows of big tenements, leaves no room for doubt as to the influence the change has had upon the children. With the disappearance of the shanties—homesteads in effect, however humble—and the coming of the tenement crowds, there has been a distinct descent in the scale of refinement among the children, if one may use the term. The crowds and the loss of home privacy, with the increased importance of the street as a factor, account for it. The general tone has been lowered, while at the same time, by reason of the greater rescue-efforts put forward, the original amount of ignorance has been reduced. The big loafer of the old day, who could neither read nor write, has been eliminated to a large extent, and his loss is our gain. The tough who has taken his place is able at least to spell his way through “The Bandits’ Cave,” the pattern exploits of Jesse James and his band, and the newspaper accounts of the latest raid in which he had a hand. Perhaps that explains why he is more dangerous than the old loafer. The transition period is always critical, and a little learning is proverbially a dangerous thing. It may be that in the day to come, when we shall have got the grip of our compulsory school law in good earnest, there will be an educational standard even for the tough, by which time he will, I think, have ceased to exist from sheer disgust, if for no other reason. At present he is in no immediate danger of extinction from such a source. It is not how much book-learning the boy can get, but how little he can get along with, and that is very little indeed. He knows how to make a little go a long way, however, and to serve on occasion a very practical purpose; as, for instance, when I read recently on the wall of the church next to my office in Mulberry Street this observation, chalked in an awkward hand half the length of the wall: “Mary McGee is engagd to the feller in the alley.” Quite apt, I should think, to make Mary show her colors and to provoke the fight with the rival “feller” for which the writer was evidently spoiling. I shall get back, farther on, to the question of the children’s schooling. It is so beset by lies ordinarily as to be seldom answered as promptly and as honestly as in the case of a little fellow whom I found in front of St. George’s Church, engaged in the æsthetic occupation of pelting the Friends’ Seminary across the way with mud. There were two of them, and when I asked them the question that estranged Tony, the wicked one dug his fists deep down in the pockets of his blue-jeans trousers and shook his head gloomily. He couldn’t read; didn’t know how; never did.

“He?” said the other, who could, “he? He don’t learn nothing. He throws stones.” The wicked one nodded. It was the extent of his education.

But if the three R’s suffer neglect among the children of the poor, their lessons in the three D’s—Dirt, Discomfort, and Disease—that form the striking features of their environment, are early and thorough enough. The two latter, at least, are synonymous terms, if dirt and discomfort are not. Any dispensary doctor knows of scores of cases of ulceration of the eye that are due to the frequent rubbing of dirty faces with dirty little hands. Worse filth diseases than that find a fertile soil in the tenements, as the health officers learn when typhus and small-pox break out. It is not the desperate diet of ignorant mothers, who feed their month-old babies with sausage, beer, and Limburger cheese, that alone accounts for the great infant mortality among the poor in the tenements. The dirt and the darkness in their homes contribute their full share, and the landlord is more to blame than the mother. He holds the key to the situation which her ignorance fails to grasp, and it is he who is responsible for much of the unfounded and unnecessary prejudice against foreigners, who come here willing enough to fall in with the ways of the country that are shown to them. The way he shows them is not the way of decency. I am convinced that the really injurious foreigners in this community, outside of the walking delegate’s tribe, are the foreign landlords of two kinds: those who, born in poverty abroad, have come up through tenement-house life to the ownership of tenement property, with all the bad traditions of such a career; and the absentee landlords of native birth who live and spend their rents away from home, without knowing or caring what the condition of their property is, so the income from it suffer no diminution. There are honorable exceptions to the first class, but few enough to the latter to make them hardly worth mentioning.

To a good many of the children, or rather to their parents, this latter statement and the experience that warrants it must have a sadly familiar sound. The Irish element is still an important factor in New York’s tenements, though it is yielding one stronghold after another to the Italian foe. It lost its grip on the Five Points and the Bend long ago, and at this writing the time seems not far distant when it must vacate for good also that classic ground of the Kerryman, Cherry Hill. It is Irish only by descent, however; the children are Americans, as they will not fail to convince the doubter. A school census of this district, the Fourth Ward, taken last winter, discovered 2,016 children between the ages of five and fourteen years. No less than 1,706 of them were put down as native born, but only one-fourth, or 519, had American parents. Of the others 572 had Irish and 536 Italian parents. Uptown, in many of the poor tenement localities, in Poverty Gap, in Battle Row, and in Hell’s Kitchen, in short, wherever the gang flourishes, the Celt is still supreme and seasons the lump enough to give it his own peculiar flavor, easily discovered through its “native” guise in the story of the children of the poor.

The case of one Irish family that exhibits a shoal which lies always close to the track of ignorant poverty is even now running in my mind, vainly demanding a practical solution. I may say that I have inherited it from professional philanthropists, who have struggled with it for more than half a dozen years without finding the way out they sought.

There were five children when they began, depending on a mother who had about given up the struggle as useless. The father was a loafer. When I took them the children numbered ten, and the struggle was long since over. The family bore the pauper stamp, and the mother’s tears, by a transition imperceptible probably to herself, had become its stock in trade. Two of the children were working, earning all the money that came in; those that were not lay about in the room, watching the charity visitor in a way and with an intentness that betrayed their interest in the mother’s appeal. It required very little experience to make the prediction that, shortly, ten pauper families would carry on the campaign of the one against society, if those children lived to grow up. And they were not to blame, of course. I scarcely know which was most to be condemned, when we tried to break the family up by throwing it on the street as a necessary step to getting possession of the children—the politician who tripped us up with his influence in the court, or the landlord who had all those years made the poverty on the second floor pan out a golden interest. It was the outrageous rent for the filthy den that had been the most effective argument with sympathizing visitors. Their pity had represented to him, as nearly as I could make out, for eight long years, a capital of $2,600 invested at six per cent., payable monthly. The idea of moving was preposterous; for what other landlord would take in a homeless family with ten children and no income?