полная версия

полная версияThe Children of the Poor

“This I do,” he explained, “to prevent them from going on strike with the hope of getting a job anywhere else. They can’t. They don’t know enough. Not only do we limit them so that a man who has worked three months in my shop and never held a needle before is just as valuable to me as one I have had five years, but we make the different parts of the suit in different places and keep Christians over the hands as cutters so that they shall have no chance to learn.”

Where we stood in his shop, a little boy was stacking some coats for removal. The manufacturer pointed him out. “Now,” he said, “this boy is not fourteen years old, as you can see as well as I. His father works here and when the Inspector comes I just call him up. He swears that the boy is old enough to work, and there the matter ends. What would you? Is it not better that he should be here than on the street? Bah!” And this successful Christian manufacturer turned upon his heel with a vexed air. It was curious to hear him, before I left, deliver a homily on the “immorality” of the sweat-shops, arraigning them severely as “a blot on humanity.”

CHAPTER VII.

THE TRUANTS OF OUR STREETS

ON my way to the office the other day, I came upon three boys sitting on a beer-keg in the mouth of a narrow alley intent upon a game of cards. They were dirty and “tough.” The bare feet of the smallest lad were nearly black with dried mud. His hair bristled, unrestrained by cap or covering of any kind. They paid no attention to me when I stopped to look at them. It was an hour before noon.

“Why are you not in school?” I asked of the oldest rascal. He might have been thirteen.

“’Cause,” he retorted calmly, without taking his eye off his neighbor’s cards, “’cause I don’t believe in it. Go on, Jim!”

I caught the black-footed one by the collar. “And you,” I said, “why don’t you go to school? Don’t you know you have to?”

The boy thrust one of his bare feet out at me as an argument there was no refuting. “They don’t want me; I aint got no shoes.” And he took the trick.

I had heard his defence put in a different way to the same purpose more than once on my rounds through the sweat-shops. Every now and then some father, whose boy was working under age, would object, “We send the child to school, as the Inspector says, and there is no room for him. What shall we do?” He spoke the whole truth, likely enough; the boy only half of it. There was a charity school around the corner from where he sat struggling manfully with his disappointment, where they would have taken him, and fitted him out with shoes in the bargain, if the public school rejected him. If anything worried him, it was probably the fear that I might know of it and drag him around there. I had seen the same thought working in the tailor’s mind. Neither had any use for the school; the one that his boy might work, the other that he might loaf and play hookey.

Each had found his own flaw in our compulsory education law and succeeded. The boy was safe in the street because no truant officer had the right to arrest him at sight for loitering there in school-hours. His only risk was the chance of that functionary’s finding him at home, and he was trying to provide against that. The tailor’s defence was valid. With a law requiring—compelling is the word, but the compulsion is on the wrong tack—all children between the ages of eight and fourteen years to go to school at least one-fourth of the year or a little more; with a costly machinery to enforce it, even more costly to the child who falls under the ban as a truant than to the citizens who foot the bills, we should most illogically be compelled to exclude, by force if they insisted, more than fifty thousand of the children, did they all take it into their heads to obey the law. We have neither schools enough nor seats enough in them. As it is, we are spared that embarrassment. They don’t obey it.

This is the way the case stands: Computing the school population upon the basis of the Federal census of 1880 and the State census of 1892, we had in New York, in the summer of 1891, 351,330 children between five and fourteen10 years. I select these limits because children are admitted to the public schools under the law at the age of five years, and the statistics of the Board of Education show that the average age of the pupils entering the lowest primary grade is six years and five months. The whole number of different pupils taught in that year was 196,307.11 The Catholic schools, parochial and select, reported a total of 35,055; the corporate schools (Children’s Aid Society’s, Orphan Asylums, American Female Guardian Society’s, etc.), 23,276; evening schools, 29,165; Nautical School, 111; all other private schools (as estimated by Superintendent of Schools Jasper), 15,000; total, 298,914; any possible omissions in this list being more than made up for by the thousands over fourteen who are included. So that by deducting the number of pupils from the school population as given above, more than 50,000 children between the ages of five and fourteen are shown to have received no schooling whatever last year. As the public schools had seats for only 195,592, while the registered attendance exceeded that number, it follows that there was no room for the fifty thousand had they chosen to apply. In fact, the year before, 3,783 children had been refused admission at the opening of the schools after the summer vacation because there were no seats for them. To be told in the same breath that there were more than twenty thousand unoccupied seats in the schools at that time, is like adding insult to injury. Though vacant and inviting pupils they were worthless, for they were in the wrong schools. Where the crowding of the growing population was greatest and the need of schooling for the children most urgent, every seat was taken. Those who could not travel far from home—the poor never can—in search of an education had to go without.

The Department of Education employs twelve truant officers, who in 1891 “found and returned to school” 2,701 truants. There is a timid sort of pretence that this was “enforcing the compulsory education law,” though it is coupled with the statement that at least eight more officers are needed to do it properly, and that they should have power to seize the culprits wherever found. Superintendent Jasper tells me that he thinks there are only about 8,000 children in New York who do not go to school at all. But the Department’s own records furnish convincing proof that he is wrong, and that the 50,000 estimate is right. That number is just about one-seventh of the whole number of children between five and fourteen years, as stated above. In January of this year a school-census of the Fourth and Fifteenth wards,12 two widely separated localities, differing greatly as to character of population, gave the following result: Fourth Ward, total number of children between five and fourteen years, 2,016;13 of whom 297 did not go to school. Fifteenth Ward, total number of children, 2,276; number of non-attendants, 339. In each case the proportion of non-attendants was nearly one-seventh, curiously corroborating the estimate made by me for the whole city.

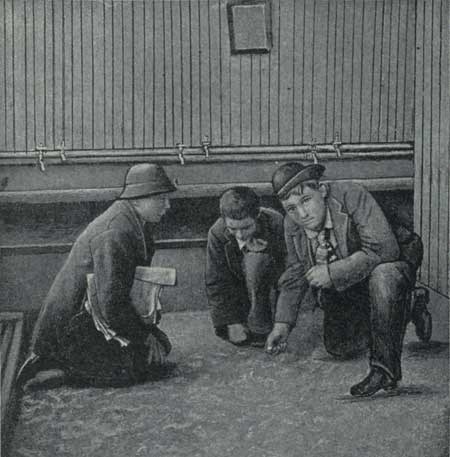

“SHOOTING CRAPS” IN THE HALL OF THE NEWSBOYS’ LODGING HOUSE.

Testimony to the same effect is borne by a different set of records, those of the reformatories that receive the truants of the city. The Juvenile Asylum, that takes most of those of the Protestant faith, reports that of 28,745 children of school age committed to its care in thirty-nine years 32 per cent. could not read when received. The proportion during the last five years was 23 per cent. At the Catholic Protectory, of 3,123 boys and girls cared for during the year 1891, 689 were utterly illiterate at the time of their reception and the education of the other 2,434 was classified in various degrees between illiterate and “able to read and write” only.14 The moral status of these last children may be inferred from the statement that 739 of them possessed no religious instruction at all when admitted. The analysis might be extended, doubtless with the same result as to illiteracy, throughout the institutions that harbor the city’s dependent children, to the State Reformatory, where the final product is set down in 75 per cent. of “grossly ignorant” inmates, in spite of the fact that more than that proportion is recorded as being of “average natural mental capacity.” In other words, they could have learned, had they been taught.

How much of this bad showing is due to the system, or the lack of system, of compulsory education, as we know it in New York, I shall not venture to say. In such a system a truant school or home would seem to be a logical necessity. Because a boy does not like to go to school, he is not necessarily bad. It may be the fault of the school and of the teacher as much as of the boy. Indeed, a good many people of sense hold that the boy who has never planned to run away from home or school does not amount to much. At all events, the boy ought not to be classed with thieves and vagabonds. But that is what New York does. It has no truant home. Its method of dealing with the truant is little less than downright savagery. It is thus set forth in a report of a special committee of the Board of Education, made to that body on November 18, 1891. “Under the law the truant agents act upon reports received from the principals of the schools. After exhausting the persuasion that they may be able to exercise to compel the attendance of truant children, and in cases which seem to call for the enforcement of the law, the agent procures the indorsement of the President of the Board of Education and the Superintendent of Schools upon his requisition for a warrant for the arrest of the truant, which warrant, under the provisions of the law, is then issued by a Police Justice. A policeman is then detailed to make the arrest, and when apprehended the truant is brought to the Police Court, where his parents or guardians are obliged to attend. Should it happen that the latter are not present, the boy is put in a cell to await their appearance. It has sometimes happened that a public-school boy, whose only offence against the law was his refusal to attend school, has been kept in a cell two or three days with old criminals pending the appearance of his parents or guardians.15 While we fully realize the importance of enforcing the laws relating to compulsory education, we believe that bringing the boys into associations with criminals in this way and making it necessary for parents to be present under such circumstances, is unjust and improper, and that criminal associations of this kind in connection with the administration of the truancy laws should not be allowed to continue. The Justice may, after hearing the facts, commit the child, who, in a majority of cases, is between eight and eleven years old, to one of the institutions designated by law. We do not think that the enforcement of the laws relating to compulsory education should at any time enforce association with criminal classes.”

But it does, all the way through. The “institutions designated by law” for the reception of truants are chiefly the Protectory and the Juvenile Asylum. In the thirty-nine years of its existence the latter has harbored 11,636 children committed to it for disobedience and truancy. And this was the company they mingled with there on a common footing: “Unfortunate children,” 8,806; young thieves, 3,097; vagrants, 3,173; generally bad boys and girls, 1,390; beggars, 542; children committed for peddling, 51; as witnesses, 50. Of the whole lot barely a hundred, comprised within the last two items, might be supposed to be harmless, though there is no assurance that they were. Of the Protectory children I have already spoken. It will serve further to place them to say that nearly one-third of the 941 received last year were homeless, while fully 35 per cent. of all the boys suffered when entering from the contagious eye disease that is the scourge of the poorest tenements as of the public institutions that admit their children. I do not here take into account the House of Refuge, though that is also one of the institutions designated by law for the reception of truants, for the reason that only about one-fifth of those admitted to it last year came from New York City. Their number was 55. The rest came from other counties in the State. But even there the percentage of truants to those committed for stealing or other crimes was as 53 to 47.

This is the “system,” or one end of it—the one where the waste goes on. The Committee spoken of reported that the city paid in 1890, $63,690 for the maintenance of the truants committed by magistrates, at the rate of $110 for every child, and that two truant schools and a home for incorrigible truants could be established and maintained at less cost, since it would probably not be necessary to send to the home for incorrigibles more than 25 per cent. of all. It further advised the creation of the special office of Truant Commissioner, to avoid dragging the children into the police courts. In his report for the present year Superintendent Jasper renews in substance these recommendations. But nothing has been done.

The situation is this, then, that a vast horde of fifty thousand children is growing up in this city whom our public school does not and cannot reach; if it reaches them at all it is with the threat of the jail. The mass of them is no doubt to be found in the shops and factories, as I have shown. A large number peddle newspapers or black boots. Still another contingent, much too large, does nothing but idle, in training for the penitentiary. I stopped one of that kind at the corner of Baxter and Grand Streets one day to catechise him. It was in the middle of the afternoon when the schools were in session, but while I purposely detained him with a long talk to give the neighborhood time to turn out, thirteen other lads of his age, all of them under fourteen, gathered to listen to my business with Graccho. When they had become convinced that I was not an officer they frankly owned that they were all playing hookey. All of them lived in the block. How many more of their kind it sheltered I do not know. They were not exactly a nice lot, but not one of them would I have committed to the chance of contact with thieves with a clear conscience. I should have feared especial danger from such contact in their case.

As a matter of fact the record of average attendance (136,413) shows that the public school per se reaches little more than a third of all the children. And even those it does not hold long enough to do them the good that was intended. The Superintendent of Schools declares that the average age at which the children leave school is twelve or a little over. It must needs be, then, that very many quit much earlier, and the statement that in New York, as in Chicago, St. Louis, Brooklyn, New Orleans, and other American cities, half or more than half the school-boys leave school at the age of eleven (the source of the statement is unknown to me) seems credible enough. I am not going to discuss here the value of school education as a preventive of crime. That it is, so far as it goes, a positive influence for good I suppose few thinking people doubt nowadays. Dr. William T. Harris, Federal Commissioner of Education, in an address delivered before the National Prison Association in 1890, stated that an investigation of the returns of seventeen States that kept a record of the educational status of their criminals showed the number of criminals to be eight times as large from the illiterate stratum as from an equal number of the population that could read and write. That census was taken in 1870. Ten years later a canvass of the jails of Michigan, a State that had an illiterate population of less than five per cent., showed exactly the same ratio, so that I presume that may safely be accepted.

In view of these facts it does not seem that the showing the public school is making in New York is either creditable or safe. It is not creditable, because the city’s wealth grows even faster than its population,16 and there is no lack of means with which to provide schools enough and the machinery to enforce the law and fill them. Not to enforce it because it would cost a great deal of money is wicked waste and folly. It is not safe, because the school is our chief defence against the tenement and the flood of ignorance with which it would swamp us. Prohibition of child labor without compelling the attendance at school of the freed slaves is a mockery. The children are better off working than idling, any day. The physical objections to the one alternative are vastly outweighed by the moral iniquities of the other.

I have tried to set forth the facts. They carry their own lesson. The then State Superintendent of Education, Andrew Draper, read it aright when, in his report for 1889, he said about the compulsory education law:

“It does not go far enough and is without an executor. It is barren of results.... It may be safely said that no system will be effectual in bringing the unfortunate children of the streets into the schools which at least does not definitely fix the age within which children must attend the schools, which does not determine the period of the year within which all must be there, which does not determine the method for gathering all needed information, which does not provide especial schools for incorrigible cases, which does not punish people charged with the care of children for neglecting their education, and which does not provide the machinery and officials for executing the system.”

CHAPTER VIII.

WHAT IT IS THAT MAKES BOYS BAD

I AM reminded, in trying to show up the causes that go to make children bad, of the experience of a certain sanitary inspector who was laboring with the proprietor of a seven-cent lodging-house to make him whitewash and clean up. The man had reluctantly given in to several of the inspector’s demands; but, as they kept piling up, his irritation grew, until at the mention of clean sheets he lost all patience and said, with bitter contempt, “Well! you needn’t tink dem’s angels!”

They were not—those lodgers of his—they were tramps. Neither are the children of the street angels. If, once in a while, they act more like little devils the opportunities we have afforded them, as I have tried to show, hardly give us the right to reproach them. They are not the kind of opportunities to make angels. And yet, looking the hundreds of boys in the Juvenile Asylum over, all of whom were supposed to be there because they were bad (though, as I had occasion to ascertain, that was a mistake—it was the parents that were bad in some cases), I was struck by the fact that they were anything but a depraved lot. Except as to their clothes and their manners, which were the manners of the street, they did not seem to be very different in looks from a like number of boys in any public school. Fourth of July was just then at hand, and when I asked the official who accompanied me how they proposed to celebrate it, he said that they were in the habit of marching in procession up Eleventh Avenue to Fort George, across to Washington Bridge, and all about the neighborhood, to a grove where speeches were made. Remembering the iron bars and high fences I had seen, I said something about it being unsafe to let a thousand young prisoners go at large in that way. The man looked at me in some bewilderment before he understood.

“Bless you, no!” he said, when my meaning dawned upon him. “If any one of them was to run away that day he would be in eternal disgrace with all the rest. It is a point of honor with them to deserve it when they are trusted. Often we put a boy on duty outside, when he could walk off, if he chose, just as well as not; but he will come in in the evening, as straight as a string, only, perhaps, to twist his bed-clothes into a rope that very night and let himself down from a third-story window, at the risk of breaking his neck. Boys will be boys, you know.”

But it struck me that boys whose honor could be successfully appealed to in that way were rather the victims than the doers of a grievous wrong, being in that place, no matter if they had stolen. It was a case of misdirection, or no direction at all, of their youthful energies. There was one little fellow in the Asylum band who was a living illustration of this. I watched him blow his horn with a supreme effort to be heard above the rest, growing redder and redder in the face, until the perspiration rolled off him in perfect sheets, the veins stood out swollen and blue and it seemed as if he must burst the next minute. He was a tremendous trumpeter. I was glad when it was over, and patted him on the head, telling him that if he put as much vim into all he had to do, as he did into his horn, he would come to something great yet. Then it occurred to me to ask him what he was there for.

“’Cause I was lazy and played hookey,” he said, and joined in the laugh his answer raised. The idea of that little body, that fairly throbbed with energy, being sent to prison for laziness was too absurd for anything.

The report that comes from the Western Agency of the Asylum, through which the boys are placed out on farms, that the proportion of troublesome children is growing larger does not agree with the idea of laziness either, but well enough with the idleness of the street, which is what sends nine-tenths of the boys to the Asylum. Satan finds plenty of mischief for the idle hands of these lads to do. The one great point is to give them something to do—something they can see the end of, yet that will keep them busy right along. The more ignorant the child, the more urgent this rule, the shorter and simpler the lesson must be. Over in the Catholic Protectory, where they get the most ignorant boys, they appreciate this to the extent of encouraging the boys to a game of Sunday base-ball rather than see them idle even for the briefest spell. Of the practical wisdom of their course there can be no question.

“I have come to the conclusion,” said a well-known educator on a recent occasion, “that much of crime is a question of athletics.” From over the sea the Earl of Meath adds his testimony: “Three fourths of the youthful rowdyism of large towns is owing to the stupidity, and, I may add, cruelty, of the ruling powers in not finding some safety-valve for the exuberant energies of the boys and girls of their respective cities.” For our neglect to do so in New York we are paying heavily in the maintenance of these costly reform schools. I spoke of the chance for romping and play where the poor children crowd. In a Cherry Street hall-way I came across this sign in letters a foot long: “No ball-playing, dancing, card-playing, and no persons but tenants allowed in the yard.” It was a five-story tenement, swarming with children, and there was another just as big across that yard. Out in the street the policeman saw to it that the ball-playing at least was stopped, and as for the dancing, that, of course, was bound to collect a crowd, the most heinous offence known to him as a preserver of the peace. How the peace was preserved by such means I saw on the occasion of my discovering that sign. The business that took me down there was a murder in another tenement just like it. A young man, hardly more than a boy, was killed in the course of a midnight “can-racket” on the roof, in which half the young people in the block had a hand night after night. It was their outlet for the “exuberant energies” of their natures. The safety-valve was shut, with the landlord and the policeman holding it down.

It is when the wrong outlet has thus been forced that the right and natural one has to be reopened with an effort as the first condition of reclaiming the boy. The play in him has all run to “toughness,” and has first to be restored. “We have no great hope of a boy’s reformation,” writes Mr. William F. Round, of the Burnham Industrial Farm, to a friend who has shown me his letter, “till he takes an active part and interest in out-door amusements. Plead with all your might for play-grounds for the city waifs and school-children. When the lungs are freely expanded, the blood coursing with a bound through all veins and arteries, the whole mind and body in a state of high emulation in wholesome play, there is no time or place for wicked thought or consequent wicked action and the body is growing every moment more able to help in the battle against temptation when it shall come at other times and places. Next time another transit company asks a franchise make them furnish tickets to the parks and suburbs to all school-children on all holidays and Saturdays, the same to be given out in school for regular attendance, as a method of health promotion and a preventive of truancy.” Excellent scheme! If we could only make them. It is five years and over now since we made them pass a law at Albany appropriating a million dollars a year for the laying out of small parks in the most crowded tenement districts, in the Mulberry Street Bend for instance, and practically we stand to-day where we stood then. The Mulberry Street Bend is still there, with no sign of a park or play-ground other than in the gutter. When I asked, a year ago, why this was so, I was told by the Counsel to the Corporation that it was because “not much interest had been taken” by the previous administration in the matter. Is it likely that a corporation that runs a railroad to make money could be prevailed upon to take more interest in a proposition to make it surrender part of its profits than the city’s sworn officers in their bounden duty? Yet let anyone go and see for himself what effect such a park has in a crowded tenement district. Let him look at Tompkins Square Park as it is to-day and compare the children that skip among the trees and lawns and around the band-stand with those that root in the gutters only a few blocks off. That was the way they looked in Tompkins Square twenty years ago when the square was a sand-lot given up to rioting and disorder. The police had their hands full then. I remember being present when they had to take the square by storm more than once, and there is at least one captain on the force to-day who owes his promotion to the part he took and the injuries he suffered in one of those battles. To-day it is as quiet and orderly a neighborhood as any in the city. Not a squeak has been heard about “bread or blood” since those trees were planted and the lawns and flower-beds laid out. It is not all the work of the missions, the kindergartens, and Boys’ clubs and lodging-houses, of which more anon; nor even the larger share. The park did it, exactly as the managers of the Juvenile Asylum appealed to the sense of honor in their prisoners. It appealed with its trees and its grass and its birds to the sense of decency and of beauty, undeveloped but not smothered, in the children, and the whole neighborhood responded. One can go around the whole square that covers two big blocks, nowadays, and not come upon a single fight. I should like to see anyone walk that distance in Mulberry Street without running across half a dozen.