полная версия

полная версияThe Children of the Poor

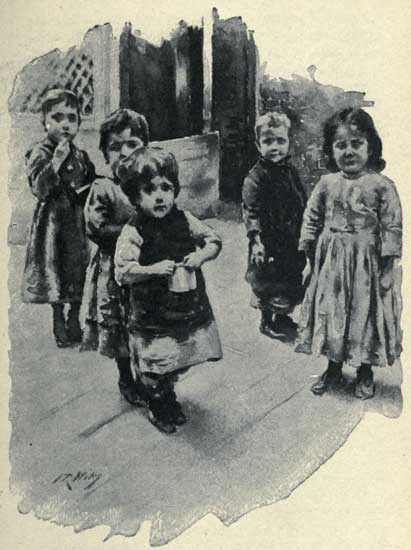

Children anywhere suffer little discomfort from mere dirt. As an ingredient of mud-pies it may be said to be not unwholesome. Play with the dirt is better than none without it. In the tenements the children and the dirt are sworn and loyal friends. In his early raids upon the established order of society, the gutter backs the boy up to the best of its ability, with more or less exasperating success. In the hot summer days, when he tries to sneak into the free baths with every fresh batch, twenty times a day, wretched little repeater that he is, it comes to his rescue against the policeman at the door. Fresh mud smeared on the face serves as a ticket of admission which no one can refuse. At least so he thinks, but in his anxiety he generally overdoes it and arouses the suspicion of the policeman, who, remembering that he was once a boy himself, feels of his hair and reads his title there. When it is a mission that is to be raided, or a “dutch” grocer’s shop, or a parade of the rival gang from the next block, the gutter furnishes ammunition that is always handy. Dirt is a great leveller;6 it is no respecter of persons or principles, and neither is the boy where it abounds. In proportion as it accumulates such raids increase, the Fresh Air Funds lose their grip, the saloon flourishes, and turbulence grows. Down from the Fourth Ward, where there is not much else, this wail came recently from a Baptist Mission Church: “The Temple stands in a hard spot and neighborhood. The past week we had to have arrested two fellows for throwing stones into the house and causing annoyance. On George Washington’s Birthday we had not put a flag over the door on Henry Street half an hour before it was stolen. When they neither respect the house of prayer or the Stars and Stripes one can feel young America is in a bad state.” The pastor added that it was a comfort to him to know that the “fellows” were Catholics; but I think he was hardly quite fair to them there. Religious enthusiasm very likely had something to do with it, but it was not the moving cause. The dirt was; in other words: the slum.

Such diversions are among the few and simple joys of the street child’s life, Not all it affords, but all the street has to offer. The Fresh Air Funds, the free excursions, and the many charities that year by year reach farther down among the poor for their children have done and are doing a great work in setting up new standards, ideals, and ambitions in the domain of the street. One result is seen in the effort of the poorest mothers to make their little ones presentable when there is anything to arouse their maternal pride. But all these things must and do come from the outside. Other resources than the sturdy independence that is its heritage the street has none. Rightly used, that in itself is the greatest of all. Chief among its native entertainments is that crowning joy, the parade of the circus when it comes to town in the spring. For many hours after that has passed, as after every public show that costs nothing, the matron’s room at Police Headquarters is crowded with youngsters who have followed it miles and miles from home, devouring its splendors with hungry eyes until the last elephant, the last soldier, or the last policeman vanished from sight and the child comes back to earth again and to the knowledge that he is lost.

If the delights of his life are few, its sorrows do not sit heavily upon him either. He is in too close and constant touch with misery, with death itself, to mind it much. To find a family of children living, sleeping, and eating in the room where father or mother lies dead, without seeming to be in any special distress about it, is no unusual experience. But if they do not weigh upon him, the cares of home leave their mark; and it is a bad mark. All the darkness, all the drudgery is there. All the freedom is in the street; all the brightness in the saloon to which he early finds his way. And as he grows in years and wisdom, if not in grace, he gets his first lessons in spelling and in respect for the law from the card behind the bar, with the big black letters: “No liquor sold here to children.” His opportunities for studying it while the barkeeper fills his growler are unlimited and unrestricted.

Someone has said that our poor children do not know how to play. He had probably seen a crowd of tenement children dancing in the street to the accompaniment of a hand-organ and been struck by their serious mien and painfully formal glide and carriage—if it was not a German neighborhood, where the “proprieties” are less strictly observed—but that was only because it was a ball and it was incumbent on the girls to act as ladies. Only ladies attend balls. “London Bridge is falling down,” with as loud a din in the streets of New York, every day, as it has fallen these hundred years and more in every British town, and the children of the Bend march “all around the mulberry-bush” as gleefully as if there were a green shrub to be found within a mile of their slum. It is the slum that smudges the game too easily, and the kindergarten work comes in in helping to wipe off the smut. So far from New York children being duller at their play than those of other cities and lands, I believe the reverse to be true. Only in the very worst tenements have I observed the children’s play to languish. In such localities two policemen are required to do the work of one. Ordinarily they lack neither spirit nor inventiveness. I watched a crowd of them having a donkey party in the street one night, when those parties were all the rage. The donkey hung in the window of a notion store, and a knot of tenement-house children with tails improvised from a newspaper, and dragged in the gutter to make them stick, were staggering blindly across the sidewalk trying to fix them in place on the pane. They got a heap of fun out of the game, quite as much, it seemed to me, as any crowd of children could have got in a fine parlor, until the storekeeper came out with his club. Every cellar-door becomes a toboggan-slide where the children are around, unless it is hammered full of envious nails; every block a ball-ground when the policeman’s back is turned, and every roof a kite-field; for that innocent amusement is also forbidden by city ordinance “below Fourteenth Street.”

PRESENT TENANTS OF JOHN ERICSSON’S OLD HOUSE NOW THE BEACH STREET INDUSTRIAL SCHOOL.

It is rather that their opportunities of mischief are greater than those of harmless amusement; made so, it has sometimes seemed to me, with deliberate purpose to hatch the “tough.” Given idleness and the street, and he will grow without other encouragement than an occasional “fanning” of a policeman’s club. And the street has to do for a playground. There is no other. Central Park is miles away. The small parks that were ordered for his benefit five years ago exist yet only on paper. Games like kite-flying and ball-playing, forbidden but not suppressed, as happily they cannot be, become from harmless play a successful challenge of law and order, that points the way to later and worse achievements. Every year the police forbid the building of election bonfires, and threaten vengeance upon those who disobey the ordinance; and every election night sees the sky made lurid by them from one end of the town to the other, with the police powerless to put them out. Year by year the boys grow bolder in their raids on property when their supply of firewood has given out, until the destruction wrought at the last election became a matter of public scandal. Stoops, wagons, and in one place a show-case, containing property worth many hundreds of dollars, were fed to the flames. It has happened that an entire frame house has been carried off piecemeal, and burned up election night. The boys, organized in gangs, with the one condition of membership that all must “give in wood,” store up enormous piles of fuel for months before, and though the police find and raid a good many of them, incidentally laying in supplies of kindling-wood for the winter, the pile grows again in a single night, as the neighborhood reluctantly contributes its ash-barrels to the cause. The germ of the gangs that terrorize whole sections of the city at intervals, and feed our courts and our jails, may without much difficulty be discovered in these early and rather grotesque struggles of the boys with the police.

Even on the national day of freedom the boy is not left to the enjoyment of his firecracker without the ineffectual threat of the law. I am not defending the firecracker, but arraigning the failure of the law to carry its point and maintain its dignity. It has robbed the poor child of the street-band, one of his few harmless delights, grudgingly restoring the hand-organ, but not the monkey that lent it its charm. In the band that, banished from the street, sneaks into the back-yard, horns and bassoons hidden under bulging coats, the boy hails no longer the innocent purveyor of amusement, but an ally in the fight with the common enemy, the policeman. In the Thanksgiving Day and New Year parades which the latter formally permits, he furnishes them with the very weapon of gang organization which they afterward turn against him to his hurt.

And yet this boy who, when taken from his alley into the country for the first time, cries out in delight, “How blue the sky and what a lot of it there is!”—not much of it at home in his barrack—has in the very love of dramatic display that sends him forth to beat a policeman with his own club or die in the attempt, in the intense vanity that is only a perverted form of pride, capable of any achievement, a handle by which he may be most easily grasped and led. It cannot be done by gorging him en masse with apples and gingerbread at a Christmas party.7 It can be done only by individual effort, and by the influence of personal character in direct contact with the child—the great secret of success in all dealings with the poor. Foul as the gutter he comes from, he is open to the reproach of “bad form” as few of his betters. Greater even than his desire eventually to “down” a policeman, is his ambition to be a “gentleman,” as his sister’s to be a “lady.” The street is responsible for the caricature either makes of the character. On a play-bill I saw in an East Side street, only the other day, this repertoire set down: “Thursday—The Bowery Tramp; Friday—The Thief.” It was a theatre I knew newsboys, and the other children of the street who were earning money, to frequent in shoals. The play-bill suggested the sort of training they received there.

I wish I might tell the story of some of these very lads whom certain enthusiastic friends of mine tried to reclaim on a plan of their own, in which the gang became a club and its members “Knights,” who made and executed their own laws; but I am under heavy bonds of promises made to keep the peace on this point. The fact is, I tried it once, and my well-meant effort made no end of trouble. I had failed to appreciate the stride of civilization that under my friends’ banner marched about the East Side with seven-league boots. They read the magazines down there and objected, rather illogically, to being “shown up.” The incident was a striking revelation of the wide gap between the conditions that prevail abroad and those that confront us. Fancy the Westminster Review or the Nineteenth Century breeding contention among the denizens of East London by any criticism of their ways? Yet even from Hell’s Kitchen had I not long before been driven forth with my camera by a band of angry women, who pelted me with brickbats and stones on my retreat, shouting at me never to come back unless I wanted my head broken, or let any other “duck” from the (mentioning a well-known newspaper of which I was unjustly suspected of being an emissary) poke his nose in there. Reform and the magazines had not taken that stronghold of toughdom yet, but their vanguard, the newspapers, had evidently got there.

“It only shows,” said one of my missionary friends, commenting upon the East Side incident, “that we are all at sixes and at sevens here.” It is our own fault. In our unconscious pride of caste most of us are given to looking too much and too long at the rough outside. These same workers bore cheerful testimony to the “exquisite courtesy” with which they were received every day in the poorest homes; a courtesy that might not always know the ways of polite society, but always tried its best to find them. “In over fifty thousand visits,” reports a physician, whose noble life is given early and late to work that has made her name blessed where sorrow and suffering add their sting to bitter poverty, “personal violence has been attempted on but two occasions. In each case children had died from neglect of parents, who, in their drunken rage, would certainly have taken the life of the physician, had she not promptly run away.” Patience and kindness prevailed even with these. The doctor did not desert them, even though she had had to run, believing that one of the mothers at least drank because she was poor and unable to find work; and now, after five years of many trials and failures, she reports that the family is at work and happy and grateful in rooms “where the sun beams in.” Gratitude, indeed, she found to be their strong point, always seeking an outlet in expression—evidence of a lack of bringing up, certainly. “Once,” she says, “the thankful fathers of two of our patients wished to vote for us, as ‘the lady doctors have no vote.’ Their intention was to vote for General Butler; we have proof that they voted for Cleveland. They have even placed their own lives in danger for us. One man fought a duel with a woman, she having said that women doctors did not know as much as men. After bar-tumblers were used as weapons the question was decided in favor of women doctors by the man. It seemed but proper that ‘the lady doctor’ was called in to bind up the wounds of her champion, while a ‘man doctor’ performed the service for the woman.”

My friends, in time, by their gentle but firm management, gained the honest esteem and loyal support of the boys whose manners and minds they had set out to improve, and through such means worked wonders. While some of their experiences were exceedingly funny, more were of a kind to show how easily the material could be moulded, if the hands were only there to mould it. One of their number, by and by, hung out her shingle in another street with the word “Doctor” over the bell (not the physician above referred to), but her “character” had preceded her, and woe to the urchin who as much as glanced at that when the gang pulled all the other bells in the block and laughed at the wrath of the tenants. One luckless chap forgot himself far enough to yank it one night, and immediately an angry cry went up from the gang, “Who pulled dat bell?” “Mickey did,” was the answer, and Mickey’s howls announced to the amused doctor the next minute that he had been “slugged” and she avenged. This doctor’s account of the first formal call of the gang in the block was highly amusing. It called in a body and showed a desire to please that tried the host’s nerves not a little. The boys vied with each other in recounting for her entertainment their encounters with the police enemy, and in exhibiting their intimate knowledge of the wickedness of the slums in minutest detail. One, who was scarcely twelve years old, and had lately moved from Bayard Street, knew all the ins and outs of the Chinatown opium dives, and painted them in glowing colors. The doctor listened with half-amused dismay, and when the boys rose to go, told them she was glad they had called. So were they, they said, and they guessed they would call again the next night.

“Oh! don’t come to-morrow,” said the doctor, in something of a fright; “come next week!” She was relieved upon hearing the leader of the gang reprove the rest of the fellows for their want of style. He bowed with great precision, and announced that he would call “in about two weeks.”

The testimony of these workers agrees with that of most others who reach the girls at an age when they are yet manageable, that the most abiding results follow with them, though they are harder to get at. The boys respond more readily, but also more easily fall from grace. The same good and bad traits are found in both; the same trying superficiality—which merely means that they are raw material; the same readiness to lie as the shortest cut out of a scrape; the same generous helpfulness, characteristic of the poor everywhere. Out of the depth of their bitter poverty I saw the children in the West Fifty-second Street Industrial School, last Thanksgiving, bring for the relief of the aged and helpless and those even poorer than they such gifts as they could—a handful of ground coffee in a paper bag, a couple of Irish potatoes, a little sugar or flour, and joyfully offer to carry them home. It was on such a trip I found little Katie. In her person and work she answered the question sometimes asked, why we hear so much about the boys and so little of the girls; because the home and the shop claim their work much earlier and to a much greater extent, while the boys are turned out to shift for themselves, and because, therefore, their miseries are so much more commonplace, and proportionally uninteresting. It is a woman’s lot to suffer in silence. If occasionally she makes herself heard in querulous protest; if injustice long borne gives her tongue a sharper edge than the occasion seems to require, it can at least be said in her favor that her bark is much worse than her bite. The missionary who complains that the wife nags her husband to the point of making the saloon his refuge, or the sister her brother until he flees to the street, bears testimony in the same breath to her readiness to sit up all night to mend the clothes of the scamp she so hotly denounces. Sweetness of temper or of speech is not a distinguishing feature of tenement-house life, any more among the children than with their elders. In a party sent out by our committee for a summer vacation on a Jersey farm, last summer, was a little knot of six girls from the Seventh Ward. They had not been gone three days before a letter came from one of them to the mother of one of the others. “Mrs. Reilly,” it read, “if you have any sinse you will send for your child.” That they would all be murdered was the sense the frightened mother made out of it. The six came home post haste, the youngest in a state of high dudgeon at her sudden translation back to the tenement. The lonesomeness of the farm had frightened the others. She was little more than a baby, and her desire to go back was explained by one of the rescued ones thus: “She sat two mortil hours at the table a stuffin’ of herself, till the missus she says, says she, ‘Does yer mother lave ye to sit that long at the table, sis?’” The poor thing was where there was enough to eat for once in her life, and she was making the most of her opportunity.

Not rarely does this child of common clay rise to a height of heroism that discovers depths of feeling and character full of unsuspected promise. It was in March a year ago that a midnight fire, started by a fiend in human shape, destroyed a tenement in Hester Street, killing a number of the tenants. On the fourth floor the firemen found one of these penned in with his little girl and helped them to the window. As they were handing out the child, she broke away from them suddenly and stepped back into the smoke to what seemed certain death. The firemen climbing after, groped around shouting for her to come back. Half-way across the room they came upon her, gasping and nearly smothered, dragging a doll’s trunk over the floor.

“I could not leave it,” she said, thrusting it at the men as they seized her; “my mother–”

They flung the box angrily through the window. It fell crashing on the sidewalk and, breaking open, revealed no doll or finery, but the deed for her dead mother’s grave. Little Bessie had not forgotten her, despite her thirteen years.

Yet Bessie might, likely would, have been found in the front row where anything was going on or to be had, crowding with the best of them and thrusting herself and her claim forward regardless of anything or anybody else. It is a quality in the children which, if not admirable, is at least natural. The poor have to take their turn always, and too often it never comes, or, as in the case of the poor young mother, whom one of our committee found riding aimlessly in a street car with her dying baby, not knowing where to go or what to do, when it is too late. She took mother and child to the dispensary. It was crowded and they had to wait their turn. When it came the baby was dead. It is not to be expected that children who have lived the lawless life of the street should patiently put up with such a prospect. That belongs to the discipline of a life of failure and want. The children know generally what they want and they go for it by the shortest cut. I found that out, whether I had flowers to give or pictures to take. In the latter case they reversed my Hell’s Kitchen experience with a vengeance. Their determination to be “took,” the moment the camera hove in sight, in the most striking pose they could hastily devise, was always the most formidable bar to success I met. The recollection of one such occasion haunts me yet. They were serving a Thanksgiving dinner free to all comers at a charitable institution in Mulberry Street, and more than a hundred children were in line at the door under the eye of a policeman when I tried to photograph them. Each one of the forlorn host had been hugging his particular place for an hour, shivering in the cold as the line slowly advanced toward the door and the promised dinner, and there had been numberless little spats due to the anxiety of some one farther back to steal a march on a neighbor nearer the goal; but the instant the camera appeared the line broke and a howling mob swarmed about me, up to the very eye of the camera, striking attitudes on the curb, squatting in the mud in alleged picturesque repose, and shoving and pushing in a wild struggle to get into the most prominent position. With immense trouble and labor the policeman and I made a narrow lane through the crowd from the camera to the curb, in the hope that the line might form again. The lane was studded, the moment I turned my back, with dirty faces that were thrust into it from both sides in ludicrous anxiety lest they should be left out, and in the middle of it two frowsy, ill-favored girls, children of ten or twelve, took position, hand in hand, flatly refusing to budge from in front of the camera. Neither jeers nor threats moved them. They stood their ground with a grim persistence that said as plainly as words that they were not going to let this, the supreme opportunity of their lives, pass, cost what it might. In their rags, barefooted, and in that disdainful pose in the midst of a veritable bedlam of shrieks and laughter, they were a most ludicrous spectacle. The boys fought rather shy of them, of one they called “Mag” especially, as it afterward appeared with good reason. A chunk of wood from the outskirts of the crowd that hit Mag on the ear at length precipitated a fight in which the boys struggled ten deep on the pavement, Mag in the middle of the heap, doing her full share. As a last expedient I bethought myself of a dog-fight as the means of scattering the mob, and sent around the corner to organize one. Fatal mistake! At the first suggestive bark the crowd broke and ran in a body. Not only the hangers-on, but the hungry line collapsed too in an instant, and the policeman and I were left alone. As an attraction the dog-fight outranked the dinner.

This unconquerable vanity, if not turned to use for his good, makes a tough of the lad with more muscle than brains in a perfectly natural way. The newspapers tickle it by recording the exploits of his gang with embellishments that fall in exactly with his tastes. Idleness encourages it. The home exercises no restraint. Parental authority is lost. At a certain age young men of all social grades know a heap more than their fathers, or think they do. The young tough has some apparent reason for thinking that way. He has likely learned to read. The old man has not; he probably never learned anything, not even to speak the language that his son knows without being taught. He thinks him “dead slow,” of course, and lays it to his foreign birth. All foreigners are “slow.” The father works hard. The boy thinks he knows a better plan. The old man has lost his grip on the lad, if he ever had any. That is the reason why the tough appears in the second generation and disappears in the third. By that time father and son are again on equal terms, whatever those terms may be. The exception to this rule is in the poorest Irish settlements where the manufacture of the tough goes right on, aided by the “inflooence” of the police court on one side and the saloon on the other. Between the two the police fall unwillingly into line. I was in the East Thirty-fifth Street police station one night when an officer came in with two young toughs whom he had arrested in a lumber yard where they were smoking and drinking. They had threatened to kill him and the watchman, and loaded revolvers were taken from them. In spite of this evidence against them, the Justice in the police court discharged them on the following morning with a scowl at the officer, and they were both jeering at him before noon. Naturally he let them alone after that. It was one case of hundreds of like character. The politician, of course, is behind them. Toughs have votes just as they have brickbats and brass-knuckles; when the emergency requires, an assortment to suit of the one as of the other.