полная версия

полная версияThe Children of the Poor

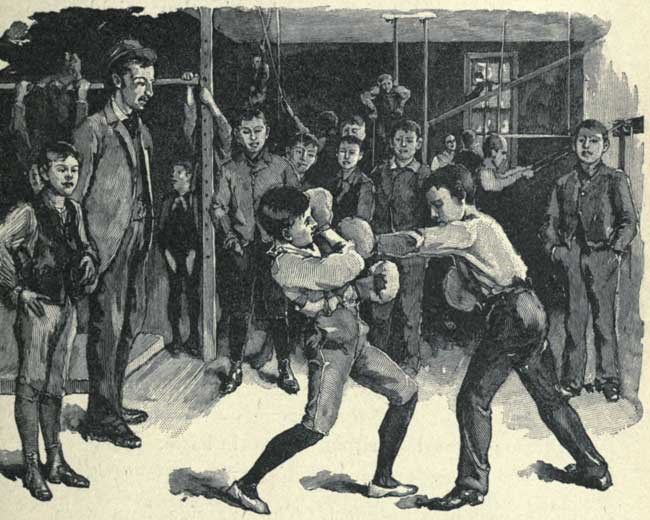

A BOUT WITH THE GLOVES IN THE BOYS’ CLUB OF CALVARY PARISH.

A small sign, with the words “Wayside Boys’ Club,” hung for a while over the Third Avenue door of the Bible House. Two years ago it was taken down; the club had been merged in the Boys’ Club of Grace Mission, in East Thirteenth Street. The members were all little fellows. They were soon made aware that they had fallen among strangers who, boylike, proposed to investigate them and to test their prowess before letting them in on equal terms. Within a week, says Mr. Wendell, this note came to their patroness in the Bible House:

“Dear Mrs. –:

“Would you please come and see to our Wayside Boys’ Club; that the first time it was open it was very nice, and after that near every boy in that neighborhood came walking in. And if you would be so kind to come and put them out it would be a great pleasure to us.

“Mrs. –, the club is not nice any more, and when we want to go home, the boys would wait for us outside, and hit you.

“Mrs. –, since them boys are in the club we don’t have any games to play with, and if we do play with the games, they come over to us and take it off us.

“And by so doing please oblige,

——, President,——, Vice-President,——, Treasurer,——, Secretary,——, Floor Manager.“Please excuse the writing. I was in haste.

“–, Treasurer.”The appeal had its effect. The Wayside boys were rescued and there has been quiet in Thirteenth Street since. They have got a new house now, and are looking hopefully forward to the day when “near every boy in that neighborhood,” shall “come walking in” upon an errand of peace.

Most of the clubs close in the summer months, when it has heretofore been supposed that few of the boys would attend. The experience of the Boys’ Club in St. Mark’s Place, which this past summer was kept open a full month later than usual and experienced no such collapse, although the park across the street might be supposed to be an extra attraction on warm evenings, suggests that there is some mistake about this which it would be worth while to find out. The street is no less dangerous to the boy in summer because it is more crowded. The Free Reading-Room for boys in West Fourteenth Street is open all the year round, and though the attendance in summer decreases one-half, yet the rooms are never empty.

The wish expressed by the President of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, in a public utterance a year ago, that there might be a boys’ club for every ward in the city, has been more than fulfilled. There are more boys’ clubs nowadays than there are wards, though I am not sure that they are so distributed that each has one. There are some wards in which twenty might not come amiss. A directory of the local gangs, which might be obtained by consultation with the corner-grocers and with the policeman on the beat after a “scrap” with the boys, would be a good guide to the right spots and also in the choice of managers. Something over a year ago a club was opened in Bleecker Street that forthwith took on the character of a poultice upon a rather turbulent neighborhood. In the second week more than a hundred boys crowded to its meetings. It “drew” entirely too well. When I looked for it this fall, it was gone—“thank goodness!” said the owner of the tenement, a little woman who kept a shop across the street, with a sigh of relief that spoke volumes. Yet she had no more definite complaint to make than what might be inferred from the emphasis she put on the words “them boys!” A friend of the club, or of some of the boys belonging to it, whom I hunted up, interpreted the sigh and the emphasis. The boys got the upper hand, he said. They had just then made a fresh start under another roof and with a new manager.

Such experiences have not been uncommon, and, as it often happens when inquiry is pursued in the right spirit, the mistakes they buoyed have been the greatest successes of the cause. There has been enough of the other kind too. Any club manager can tell of cases, lots of them, in which the club has been the stepping-stone of the boy to a useful career. In some cases the boys, having outgrown their club, have carried on the work unaided and organized young men’s societies on a plane of in-door respectability that has raised an effectual barrier against the gang and its club-room, the saloon. These things show what a hold the idea has upon the boy and how much more might be made of it. So far, private benevolence has had the field to itself, properly so; but there is a way in which the municipality might help without departing from safe moorings, so it seems to me. Why not lend such schools or class-rooms as are not used at night to boys’ clubs that can show a responsible management, for their meetings? In England the Recreative Evening Schools Association has accomplished something very like this by simply demonstrating its justice and usefulness. “Its object,” says Robert Archey Woods, in his work on English social movements, “is to carry on through voluntary workers evening classes in the board schools, combining instruction and recreation for boys and girls who have passed through the elementary required course. Its plan includes also the use of the schools for social clubs, and the use of school play-grounds for gymnastics and out-door games. This simple programme, as carried out, has shown how much may be accomplished through means which are close at hand. There are in London three hundred and forty-five such classes, combining manual training with entertainment, and their average attendance is ten thousand. Schools of the same kind are carried on in a hundred other places outside of London. Beside their immediate success under private efforts, these schools are bringing Parliament to see the importance of their object. Of late the Government has been assuming the care of recreative evening classes, little by little, and it looks as if ultimately all the work of the Evening Schools Association would be undertaken by the school boards.” I am not advocating the surrender of the boys’ club to our New York School Board. I am afraid it would gain little by it and lose too much. But they might be trusted as landlords, if not as managers. The rent is always the heaviest item in the expense account of a boys’ club, for the lads must have room. If cramped, they will boil over and make trouble. If this item were eliminated, the cause might experience a boom that would more than repay the community for the wear and tear of the school-rooms, by a reduction in the outlay for jails and police courts. There would be another advantage in the introduction of the school to the boy in the rôle of a friend, which might speed the work of the truant officer. I cannot see any serious objection to such a proposition. I have no doubt there are school trustees who can see a whole string of them; but I should not be surprised if they all came to this, that the schools are not for any such purpose. To this it would be a sufficient answer that the schools belong to the people.

LINING UP FOR THE GYMNASIUM.

Another suggestion came home to me with force while watching the drill of the Battalion Club at St. George’s one night recently. It has long been the favorite idea of a friend and neighbor of mine, who is an old army officer and has seen service in the field, that a summer camp for boys from the city tenements could be established somewhere in the mountains at a safe distance from tempting orchards, where an army of them might be drilled with immense profit to themselves and to everybody. He will have it that they could be managed as easily as an equal number of men, with the right sort of organization and officers, and as in his business he runs along smoothly with four or five hundred girls under his command, I am bound to defer to his judgment, however much my own may rebel, particularly as he would be acting out my own convictions, after all, in his wholesale way. In any event the experiment might be tried with a regiment if not with an army, and it would be a very interesting one. The boys would have lots of chance for wholesome play as well as drill, and would get no end of fun out of it. The possible hardships of camping out would have no existence for them. As for any lasting good to come of it, outside of physical benefits, I think the discipline alone, with what it stands for, would cover that. In the reform schools, where they have military drill, they have found it their most useful ally in dealing with the worst and wildest class of the boys. It is the bump of organization that is touched again there. Resistance ceases of itself and the boys fall into line. Too much can be made of discipline, of course. The body may be drilled until it is a mere machine and the real boy is dead. But that has nothing to do with such an experiment as I spoke of. That is the concern of reform schools, and I do not think they are in any danger of overdoing it.

I spoke of managing the girls. It is just the same with them. I have had the “gang” in mind as the alternative of the club, and therefore have dealt so far only with their brothers. Girls do not go in gangs, thank goodness, at least not yet in New York. They flock, until the boys scatter them and drive them off one by one. But the same instinct of self-government is in them. They take just as kindly to the club. The Neighborhood Guild, the College Settlement, and various church and philanthropic societies, carry on such clubs with great success. The girls sew, darn stockings, cook, make their own dresses, and run their own meetings with spirit when the boys are made to keep their profaning hands off. On occasion they develop the same rugged independence with an extra feminine touch to it, that is, a mixture of dash and spite. I recall the experience of a band of early philanthropists, who, a score of years ago or more, bought the Big Flat in the Sixth Ward and fitted it up as a boarding-house for working girls. They filled it without any trouble, though with a rather better grade of boarders than they had expected. No sooner were the girls in possession than they promptly organized and “resolved” that the management should make no rules for the house without first submitting them to their body for approval. Philanthropy chose the least pointed horn of the dilemma, and retired from the field. The Big Flat, from a model boarding-house became a very bad tenement, and the boarders’ club dissolved, to the loss and injury of a posterity that was distinctly poorer and duller, no less for the want of the club than for the possession of the tenement.

The boys’ club was born of the struggle of the community with the street, as a measure of self-defence. It has proven a useful war-club too, but its conquests have been the conquests of peace. It has been the kernel of success in many a philanthropic undertaking, secular and religious alike. In the plan of the Free Reading-Room for Working Boys, of which I made mention, it is used as a battering-ram in an attack upon the saloon. The Free Reading-Room was organized some nine or ten years ago by the Loyal Legion Temperance Society. It has been popular with lads of all ages from the very start, not least on account of the club or clubs which they were encouraged to found—literary societies they call them there. The Superintendent found them helpful, too, as a means of interesting the boys, by debate and otherwise, in the cause of temperance which he had at heart. The first thing a boys’ club casts about for after the offices have been manned and the by-laws made hard and fast, is a cause. One of young boys, that had been in existence a month or less at the College Settlement, almost took the ladies’ breath away by announcing one day that it had decided to expel any boy who smoked or got drunk. The Free Reading-Room gives ample opportunity for the exercise of this spirit of convert zeal, when it manifests itself. The average nightly attendance last year was seventy-one, and a good deal larger than that in winter. The boys came from as far south as Houston Street, nearly a mile below, and from Forty-second Street, a mile and half to the north, in all kinds of weather.

The doors of the reading-room stand wide open on Sunday as on week-day nights. With singing, and talks on serious or religious subjects in a vein the boys can follow, they try to give to the proceedings a Sabbath turn of which the impression may abide with them. The regular Sunday-School exercises have, I am told by the Superintendent, been abandoned, and the present less formal, but more effective, programme substituted. One has need of being wiser than the serpent if he would build effectually in this field among the poor of many races and faiths that swarm in New York’s tenements, and he must make his foundation very broad. The great thing for the boys is that the room is not closed against them on the very night in all the week when they need it most. I think we are coming at last to understand what a trap we have been digging for the young in our great cities, when we thought to save them from temptation, by shutting every door but that of the church against them on the day when the devil was busiest finding mischief for their idle hands to do, while narrowing that down to the size of a wicket-gate with our creeds and confessions. The poor bury their dead on Sunday to save the loss of a day’s pay. Poverty has given over their one day of rest to their sorrows. Is it likely that any attempt to rob it of its few harmless joys should win them over? It is the shadow of bigotry and intolerance falling across it that has turned healthy play into rioting and moral ruin. Open the museums, the libraries, and the clubs on Sunday, and the church that draws the bolt will find the tide of reawakened interest that will set in strong enough to fill its own pews, too, to overflowing.

CHAPTER XIV.

THE OUTCAST AND THE HOMELESS

UNDER the heading “Just one of God’s Children,” one of the morning newspapers told the story last winter of a newsboy at the Brooklyn Bridge, who fell in a fit with his bundle of papers under his arm, and was carried into the waiting-room by the bridge police. They sent for an ambulance, but before it came the boy was out selling papers again. The reporters asked the little dark-eyed news-woman at the bridge entrance which boy it was.

“Little Maher it was,” she answered.

“Who takes care of him?”

“Oh! no one but God,” said she, “and he is too busy with other folks to give him much attention.”

Little Maher was the representative of a class that is happily growing smaller year by year in our city. It is altogether likely that a little inquiry into his case could have placed the responsibility for his forlorn condition considerably nearer home, upon someone who preferred giving Providence the job to taking the trouble himself. There are homeless children in New York. It is certain that we shall always have our full share. Yet it is equally certain that society is coming out ahead in its struggle with this problem. In ten years, during which New York added to her population one-fourth, the homelessness of our streets, taking the returns of the Children’s Aid Society’s lodging-houses as the gauge, instead of increasing proportionally, has decreased nearly one-fifth; and of the Topsy element, it may be set down as a fact, there is an end.

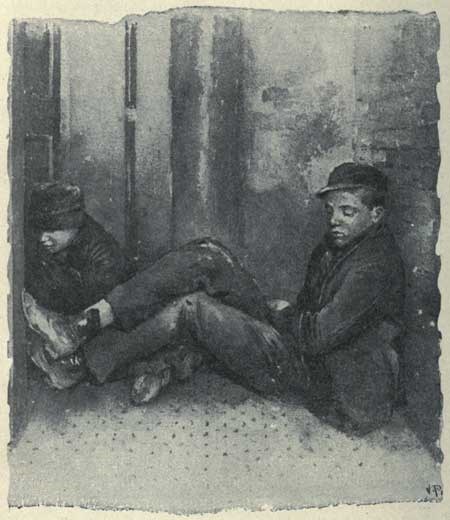

A SNUG CORNER ON A COLD NIGHT.

If we were able to argue from this a corresponding improvement in the general lot of the poor, we should be on the high road to the millennium. But it is not so. The showing is due mainly to the perfection of organized charitable effort, that proceeds nowadays upon the sensible principle of putting out a fire, viz., that it must be headed off, not run down, and therefore concerns itself chiefly about the children. We are yet a long, a very long way from a safe port. The menace of the Submerged Tenth has not been blotted from the register of the Potter’s Field, and though the “twenty thousand poor children who would not have known it was Christmas,” but for public notice to that effect, be a benevolent fiction, there are plenty whose brief lives have had little enough of the embodiment of Christmas cheer and good-will in them to make the name seem like a bitter mockery. Yet, when all is said, this much remains, that we are steering the right course. Against the drift and the head-winds of an unparalleled immigration that has literally drained the pauperism of Europe into our city for two generations, against the false currents and the undertow of the tenement in our social life, we are making headway at last.

Every homeless child rescued from the street is a knot made, a man or a woman saved, not for this day only, but for all time. What if there be a thousand left? There is one less. What that one more on the wrong side of the account might have meant will never be known till the final reckoning. The records of jails and brothels and poor-houses, for a hundred years to come, might but have begun the tale.

When, in 1849, the Chief of Police reported that in eleven wards there were 2,955 vagrants and dissolute children under fifteen years of age, the boys all thieves and the girls embryo prostitutes, and that ten per cent. of the entire child population of school age in the city were vagrants, there was no Children’s Aid Society to plead their cause. There was a reformatory, and that winter the American Female Guardian Society was incorporated, “to prevent vice and moral degradation;” but Mr. Brace had not yet found his life-work, and little Mary Ellen had not been born. The story of the legacy her sufferings left to the world of children I have briefly told, and in the chapter on Industrials Schools some of the momentous results of Mr. Brace’s devotion have been set forth. The story is not ended; it never will be, while poverty and want exist in this great city. His greatest work was among the homeless and the outcast. In the thirty-nine years during which he was the life and soul of the Children’s Aid Society it found safe country homes for 84,31822 poor city children. And the work goes on. Very nearly already, the army thus started on the road to usefulness and independence equals in numbers the whole body of children that, four years before it took up its march, yielded its Lost Tenth, as the Chief of Police bore witness, to the prisons and perdition.

This great mass of children—did they all come from the street? Not all of them. Not even the larger number. But they would have got there, all of them, had not the Society blocked the way. That is how the race of Topsies has been exterminated in New York. That in this, of all fields, prevention is the true cure, and that a farmer’s home is better for the city child that has none than a prison or the best-managed public institution, are the simple lessons it has taught and enforced by example that has carried conviction at last. The conviction came slowly and by degrees. The degrees were not always creditable to sordid human nature that had put forth no hand to keep the child from the gutter, and in the effort to rescue it now saw only its selfish opportunity. There are people yet at this day, whose offers to accept “a strong and handsome girl of sixteen or so with sweet temper,” as a cheap substitute for a paid servant—“an angel with mighty strong arms,” as one of the officers of the Society indignantly put it once—show that the selfish stage has not been quite passed. Such offers are rejected with the emphatic answer: “We bring the children out because they need you, not because you need them.” The Society farms out no girls of sixteen with strong arms. For them it finds ways of earning an honest living at such wages as their labor commands, homes in the West, if they wish it, where good husbands, not hard masters, are waiting for them. But, ordinarily, its effort is to bend the twig at a much tenderer age. And in this effort it is assisted by the growth of a strong humane sentiment in the West, that takes less account of the return the child can make in work for his keep, and more of the child itself. Time was when few children but those who were able to help about the farm could be sure of a welcome. Nowadays babies are in demand. Of all the children sent West in the last two years, 14 per cent. were under five years, 43.6 per cent. over five and under ten years, 36.8 per cent. over ten and under fifteen, and only 5.3 per cent. over fifteen years of age. The average age of children sent to Western homes in 1891 by the Children’s Aid Society was nine years and forty days, and in 1892 nine years and eight months, or an average of nine years, four months, and twenty days for the two years.

It finds them in a hundred ways—in poverty-stricken homes, on the Island, in its Industrial Schools, in the street. Often they are brought to its office by parents who are unable to take care of them. Provided they are young enough, no questions are asked. It is not at the child’s past, but at its future, that these men look. That it comes from among bad people is the best reason in the world why it should be put among those that are good. That is the one care of the Society. Its faith that the child, so placed, will respond and rise to their level, is unshaken after these many years. Its experience has knocked the bugbear of heredity all to flinders.

So that this one condition may be fulfilled, a constant missionary work of an exceedingly practical and business-like character goes on in the Western farming communities, where there is more to eat than there are mouths to fill, and where a man’s children are yet his wealth. When interest has been stirred in a community to the point of arousing demands for the homeless children, the best men in the place—the judge, the pastor, the local editor, and their peers—are prevailed upon to form a local committee that passes upon all applications, and judges of the responsibility and worthiness of the applicants. In this way a sense of responsibility is cultivated that is the best protection for the child in future years, should he need any, which he very rarely does. On a day set by the committee the agent arrives from New York with his little troop. Each child has been comfortably and neatly dressed in a new suit, and carries in his little bundle a Bible as a parting gift from the Society. The committee is on hand to receive them. So usually are half the mothers of the town, who divide the children among themselves and take them home to be cared for until the next day. If there are any babies in the lot, it is always hard work to make them give them up the next morning, and sometimes the company that gathers in the morning at the town hall, for inspection and apportionment among the farmers, has been unexpectedly depleted overnight. From twenty and thirty miles around, the big-hearted farmers come in their wagons to attend the show and to negotiate with the committee. The negotiations are rarely prolonged. Each picks out his child, sometimes two, often more than one the same child. The committee umpires between them. They all know each other, and the agent’s knowledge of each child, gained on the way out and perhaps through previous acquaintance, helps to make the best choice. There is no ceremony of adoption. That is left to days to come, when the child and the new home have learned to know each other, and to the watchful care of the local committee. To any questions concerning faith or previous condition that may be asked, the Society’s answer is always the same. In substance it is this:

“We do not know. Here is the child. Take him and make a good Baptist, or Methodist, or Christian of any sect of him! That is your privilege and his gain. The fewer questions you ask the better. Let his past be behind him and the future his to work out. Love him for himself.”23

And in the spirit in which the advice is given it is usually accepted. Night falls upon a joyous band returning home over the quiet country roads, the little stranger snugly stowed among his new friends, one of them already, with home and life before him.

And does the event justify the high hopes of that home journey? Almost always in the end, if the child was young enough when it was sent out. Sometimes a change has to be made. Oftener the change is of name, in the adoption that follows. Some of the boys get restless as they grow up, and “run about a good deal,” to the anguish of the committee. A few are reported as having “gone to the bad.” But even these commonly come out all right at last. One of them, of whom mention is made in the Society’s thirty-fifth annual report, turned up after long years as Mayor of his town and a member of the legislature. “We can think,” wrote Mr. Brace before his death, “of little Five Points thieves who are now ministers of the gospel or honest farmers; vagrants and street children who are men in professional life; and women who, as teachers or wives of good citizens, are everywhere respected; the children of outcasts or unfortunates whose inherited tendencies have been met by the new environment, and who are industrious and decent members of society.” Only by their losing themselves does the Society lose sight of them. Two or three times a year the agent goes to see them all. In the big ledgers in St. Mark’s Place each child who has been placed out has a page to himself on which all his doings are recorded, as he is heard of year by year. There are twenty-nine of these canvas-bound ledgers now, and the stories they have to tell would help anyone, who thinks he has lost faith in poor human nature, to pick it up with the vow never to let go of it again. I open one of them at random, and copy the page—page 289 of ledger No. 23. It tells the story of an English boy, one of four who were picked up down at Castle Garden twelve years ago. His mother was dead, and he had not seen his father for five years before he came here, a stowaway. He did not care, he said, where they sent him, so long as it was not back to England: