полная версия

полная версияThe Children of the Poor

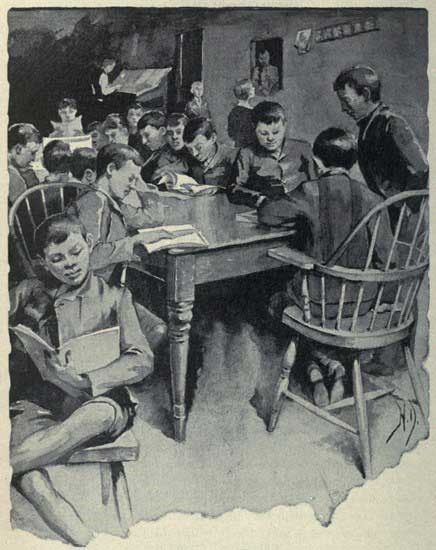

These doings include, nowadays, more than amusements and games. They made the beginning, and they are yet the means of bringing the boys in. Once there, as many as choose may join classes in writing, in book-keeping, singing, and modelling; those who come merely for fun can have all they want, on condition that they pay their respects to the wash-room and keep within the bounds of the house. This they do with the aid of the Superintendent and his assistants, who are chosen from among the bigger boys and manage to preserve order marvellously well with very little show of authority, all considered. The present Superintendent, Mr. Tyrrell, still nurses the memory of a pair of black eyes he achieved in the management of a “tough” club in Macdougal Street, where the boys came with “billies” and pistols in their hip-pockets and taught him the secret of club management in their own way. He puts it briefly this way: “It is just a question of who is to be boss.” That settled, things run smoothly enough if the right party is on top.

In justice to the Tompkins Square boys, it should be said that the question with them once for all was decided by the missionary’s coffee and cakes. If there was ever a passing disposition to forget it, “Pop’s” blighting eye helped the club to recall it in no time. Pop was the doorkeeper, and a cripple, with a single mind. His one conscious purpose in life was to keep order in the club, and he was blessed beyond most mortals in attaining his ambition, if blessed in nothing else. Under different auspices Pop might have been a rare bruiser, for, cripple that he was, he was as strong as he was determined. Under the humanizing influences that had conquered Tompkins Square he became one of the jewels of the Boys’ Club. If a round in the boxing-room threatened to wind up in a “slugging match;” if luck had gone against a boy at the game of “pot-cheese” until he felt that he must avenge his defeat by thumping his adversary, or burst—Pop’s stern glance transfixed the offender and pointed him to the street, silent and meek, all the fight taken out of him on the spot. The boys liked him for all that, perhaps just because they were a little afraid of him, and when Pop died last summer, at the age of twenty-two, after ten years of faithful attendance upon the basement-door in St. Mark’s Place, many an honest sob was gulped down at his funeral behind a dirty and tattered cap. It is not the style for boys to cry in Tompkins Square, but it is the style to honor the memory of a dead friend, and the Square never saw such a funeral as poor Pop’s. The boys chipped in and bought a gorgeous floral pillow for his coffin. So soft a pillow Pop never knew in life.

Many a little account in the club’s penny savings-bank was wiped out to do Pop that last good turn; but the Superintendent cashed all demands without a remonstrance. It is not often the money is drawn with so lofty a purpose. Most of the depositors earn a few pennies selling newspapers or doing errands. Their accounts are seldom large. In the aggregate they make up quite a little sum, however. On a certain night last June, when I was there, the bank contained almost a hundred dollars, in deposits ranging from ten cents up to nearly five dollars. That week the Superintendent had cashed sixteen books; the smallest had eleven cents to the credit of its owner, who had been greatly taken with a mouth-organ and had withdrawn his capital to buy it. Another had been saving up for a pair of boots. There were a few capitalists in the club, who, when they got a dollar and a half or two dollars together, transferred them to the Bowery Bank, where they kept an account. It was easy to predict a successful business career for these; not so with the general run, who were anything but steady depositors, though the Superintendent gave them the credit that “very few drew out their money till they had fifty cents in bank.”

If the club has developed no great financiers, it has at least brought out one latent genius in a young sculptor who has graduated from the modelling class into an art museum, and was at last accounts preparing to go abroad and spend his accumulated savings in the pursuit of further knowledge. A short time before the visit of which I speak, a sudden crisis had made the old class in “First Aid to the Injured” come out strong under difficulties. A man had fallen down the basement-stairs into the club-room, in an epileptic fit. It was three years since the boys had been taught how to manage till the doctor came, in case of accident, but they rose to the emergency with a jump. One unbuttoned the man’s collar, another slapped his hands, while a third yelled for a dollar to put between his teeth. It had not occurred to the young surgeon who taught the boys the first principles of his profession that dollars are rather scarcer about Tompkins Square than on the Avenue, and this oversight came near upsetting the good done by the rest of his teaching. There was no dollar, not even a quarter, in the crowd, and the man lay gritting his teeth until one of the rescuers, less literal but more practical than the rest, suggested a pencil or a pocket-knife and broke the spell.

The mass of the boys come in nightly just to have a good time, and they have it. They play at parchesi and messenger-boy with an ardor that leaves them no time to care what visitors come and go. Like street boys everywhere, they have a special fondness for games that admit the dice as an element. Gambling is in the very air of the street, and is encouraged in a hundred hidden ways the police rarely discover. Small candy stores and grocery back-rooms harbor policy shops, lotteries, and regular gambling hells, where the boys are taught how to buck the tiger on a penny scale. In the club games the dice are robbed of their power for evil. It is the environment here again that makes the difference. It has made a vast difference in the boy who once stalked in, hat on the back of his head, and grimy fists in his breeches’ pockets until Pop’s stony eye caught his. Now he hangs up his hat upon entering, and goes to the wash-room without waiting to be asked by the Superintendent if there is no soap and water where he comes from. Then he gets the game or the book he wants, surrendering his card as a check upon him until it is returned. It is a precaution intended to identify the borrower in case of any damage being done to the club’s property. Such a thing as theft of book or game is not known. In his business meetings the boy debates a point of order with the skill and persistence of a trained politician. The aptitude for politics sticks out all over him; but he has some lessons of that trade to learn yet, to his harm. He has not mastered the trick of betraying a friend. Any member of his club, the Superintendent feels sure, would stand up for him and take a thrashing, if need be, should he be found in trouble on his “beat.” The “beats” that converge at St. Mark’s Place and Avenue A cover a good deal of ground. The lads come from a mile around to the Boys’ Club. Occasionally “the gang” calls in a body. One evening it is the Thirteenth Street gang, the next the Eighth Street gang, and again a detachment from Avenue A. By the first-comers it is sometimes possible to foretell the particular complexion of the clientèle of the night; but the business character of the gang is left outside on the sidewalk. Within it is amiability itself, and gradually the rough corners are rubbed off, old quarrels made up, feuds forgotten in the new companionship; the gang is merged in the club, the victory over the street won.

A BOYS’ CLUB READING-ROOM.

At Christmas and at odd seasons, when the necessary talent can be secured, entertainments are given in the club-room. Sometimes the boys themselves furnish the entertainment, and then there is never a lack of critics in the audience. There never is, for that matter. Mr. Evert Jansen Wendell, who has been one of the boys’ best friends, tells some amusing things about his experience at such gatherings. Ice-cream is always intensely popular as a side issue. Some of the boys never fail to wrap a piece up in paper, or put it in the pocket without wrapping, to take home to the baby sister or brother. Only one, to Mr. Wendell’s knowledge, ever refused ice-cream at an entertainment, and he explained, by way of apology, that he had had the colic all day and his mother had told him “she’d lick him if he took any.” For a dignified missionary, who in telling the boys about the spread of the Gospel in the Far East, proposed to illustrate heathen customs by arraying himself in native costumes, brought along for the purpose, it must have been embarrassing to a degree to be cautioned by the audience to “keep his shirt on.” But his mishap was as nothing to what befell a young lady, the daughter of a wealthy and distinguished financier, who with infinite trouble had persuaded her father to assist at a certain festive occasion in her favorite club. He was an amateur with the magic lantern, the boys’ dear delight, and took it down to amuse them. Mr. Wendell tells what followed:

The show was progressing famously, and the daughter was beaming with pride, when one of the boys suddenly beckoned to her, and pointing to the distinguished financier remarked:

“What der yer call dat bloke?”

“Whom do you mean?” asked the proud daughter, in a tone of much surprise, being quite unaccustomed to hearing the distinguished financier described as a “bloke.”

“I mean dat bloke over dere, settin’ off dem picturs!” replied the boy.

“What do you desire to know about him?” inquired the proud daughter, with freezing dignity.

“I want ter know what yer call one of them fellers dat sets off picturs?” persisted the boy.

“That gentleman,” said the proud daughter, in her most impressive tone, “is my father.”

“Well!” said the boy, surveying her with supreme contempt, “don’t yer know yer own father’s trade?”

The Boys’ Club has had many followers. Some aim at teaching the lads trades; others content themselves with trying to mend their manners, while weaning them from the street and its coarse ways. Still others keep the moral improvement in view as the immediate object, as it is the ultimate end. Some follow the precedent of the Boys’ Club in charging nothing for admission; other club-organizers, like the managers of the College Settlement, have found the weekly fee as necessary as home rule to encourage self-help and self-respect in the boy, and to bring out the best that is in him. Most of them have libraries suited to the children. The College Settlement has a very excellent one of more than a thousand volumes, which is in constant use. The managers report that the boys clamor for history and science, popularly presented, as boys do everywhere, while the girls mainly read fiction. The success of different plans demonstrates the futility of some pet theories on this phase of social economics at least, in the present state of knowledge on the subject. The Boys’ Club in St. Mark’s Place, for instance, is kept entirely free from religious influence of any sort, and their experience has led many of its friends to believe that success is possible only in that way. Probably in that particular case it might not have been possible on anything like such a scale in any other way. The mud of Tompkins Square testified loudly enough to that. On the other hand, the managers of some very successful and active boys’ clubs that have sprouted under Church influence and with a strong Sunday-school bias, maintain with conviction that theirs is the true and only plan. One holds that only in leaving religion out is there hope of success; the other, that there can be none without letting it in and keeping it ever in the foreground. Each sees only half the truth. It is not the profession, or lack of profession, of a principle, but the principle itself that is the condition of success—the real sympathy and interest in the children that bids them come and be welcome, that seeks to understand their needs and help them for their own sake, a religion that “beats preaching” among the poor any day. It is a question of men and of hearts, not of faith. And the poorer the children, the more friendless and forsaken, the more readily do they respond to approaches in that spirit. The testimony of a teacher in the Poverty Gap play-ground, who went up town to take charge of one where the children were better dressed and correspondingly “stuck up,” was that in all their rags and dirt the little toughs of the Gap were much the more approachable and more promising to work with.

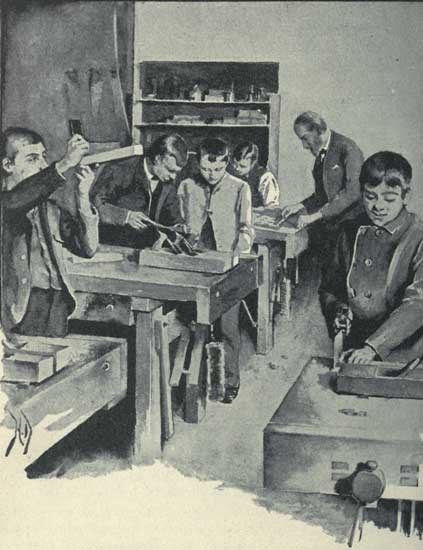

THE CARPENTER SHOP IN THE AVENUE C WORKING BOYS’ CLUB.

Naturally the Church might be expected to have found this out and to be turning the knowledge to use. And it is so. All sects are reaching now for the children in a healthy rivalry, in which the old cry about empty pews is being smothered and forgotten. Of the twenty-six boys’ clubs that are down in the Charity Organization Society’s directory, nineteen are under church roofs or patronage, and of the remaining seven I know two at least to have been founded by churches. The proportion is more than preserved, I think, in the larger number not registered there, as in all the philanthropic work of many kinds that is now going on among the children. The Roman Catholics never lost sight of the fact that the little ones were the life of the Church, which the Protestants have had, in a measure, to rediscover. Their grip upon the children was never relaxed. The parochial school has enabled them to maintain it without need of recourse to the social shifts the Protestants are adopting to regain lost prestige. Nevertheless, they have not let lie unused the best grappling-hook by which the boy might be caught and held. Their schools and churches abound with clubs and societies, organized upon a plan of absolute home-rule, under the spiritual directorship of the parish priest. Among Protestant denominations the Episcopal Church especially shows this evidence of a strong life stirring within it. The Boys’ Clubs of Calvary Parish, of St. George’s, and of many other churches, are powerful moral agents in their own neighborhoods. Everywhere some strong sympathetic personality is found to be the centre and the life of the work. It may be that the pastor himself is the moving force; or he has the faculty of stirring it in others. His young men are at work in the parish. It is a hopeful sign to find young men, to whom the sacrifice meant the loss of much that makes life beautiful, giving their time and services freely to the poor night schools and rough boys’ clubs—hopeful alike for the Church, for the boys, and for their teachers. The women have had the missionary work of the Church, as well as the pews, long enough to themselves. I am not speaking now of the college-bred men and women, who in their University Settlements pursue the plan that has proven so beneficent in England, but of another class, young business men, bank clerks, and professional men—sometimes of large means and of high social standing—whom night after night I have found thus unostentatiously working among the children with more patience than I could muster, and with the genuine love for their work that overcame all obstacles. They were not always going the errand of a church there, but that they were doing the work of the Church there could be no doubt, and doing it in a way to make it once more a living issue among the poor.

The rector of old St. George’s, which under his pastorate has grown from a forgotten temple with empty pews to be one of the strong factors in life on the crowded East Side, with Sunday congregations the great building can hardly contain, roughly outlines his plans for work among the children this way, which with variations of detail is the plan of all the churches:

“Get as many of the very little children as possible into our kindergartens, and there let them have the advantage of Christian kindergarten training, before they are old enough to go to the public schools. Keep touch of those same children and get them into the infant departments of the Sunday-school. Then take the little fellows from these, and see that in one or two nights in the week we reach them in our boys’ clubs; and then, when they are fourteen years old, they are eligible for admission to our battalion. There, by drills, exercises, etc., we hold them till they can enter our Men’s Club.”

The Sunday-school commands the approach to the club, but does not obstruct it. It stands at the door and takes the tickets. Anyone may enter, but through that door only. Once he has passed in, he is his own master. The church is content with claiming only his Sundays when the club is not in session. The experience at St. George’s on the home-rule question has been eminently characteristic. The boys could not be made to take a live interest in the club except on condition that they must run it themselves. That point yielded, they promptly boomed it to high-water mark. At present they elect their officers twice a year, to give them full swing, and one set is no sooner installed than wire-pulling begins for the next election. Once, when some trouble in the Athletic Club caused the clergy to take it in hand and appoint a president of their own choice, the membership fell off so rapidly that it was on the point of collapse when the tide was turned by a bold stroke. The managers announced a free election. The boys returned with a rush, put opposition tickets in the field, and amid intense enthusiasm over three hundred and fifty out of a total of four hundred votes were cast. The club was saved. It has been popular ever since.

The payment of monthly dues was found at St. George’s to be equally essential to success. “The boys know that they have to pay,” said the young clergyman, who quietly superintends their doings; “if they didn’t, it wouldn’t be a right club.” So they pay their pennies and enjoy the independence of it. The result has been a transformation in which the entire neighborhood rejoices. “Four years ago,” said their friend, the clergyman, “these same boys stoned us and carried on like the toughs they were. Now we have got here a lot of young gentlemen and loyal friends.” Every week-day night the Parish House in East Sixteenth Street resounds with their merriment; on Saturday, with the roll of drums and crash of martial music. Then the Battalion Club meets for drill under the instruction of a former officer in the United States Army. In their natty uniforms the lads are good to look upon, and thoroughly enjoy the exercises, as any boy of spirit would.

The Little Boys’ Club languished somewhat for want of a definite programme until the happy idea of a series of talks on elementary chemistry and physics was hit upon. An eminently practical turn was given to the talks by taking the boys to the gas-house, for instance, when gas was up for discussion; to the ship-yard, when boat-building was the topic; to the water-works, when it was water; and to see the great dynamos at work, when they were grappling with the subject of electricity. Afterward the boys were made to tell in writing what they had seen, and some of them told it surprisingly well, showing that they had made excellent use of their eyes and their brains. There is a limit, unfortunately, to the range of subjects that can be illustrated to advantage in that way; the managers had come to the end of their tether, and were puzzling over the question what to do next, when a friend of the club gave it several thousand dollars with which to fit up a manual training-school. Since then it has been in clover. A house was hired in East Eleventh Street and transformed into a carpenter-shop, and preparations to open it were in progress when these pages were sent to the printer. The club then had over two hundred members. It will probably have twice as many before the winter is over.

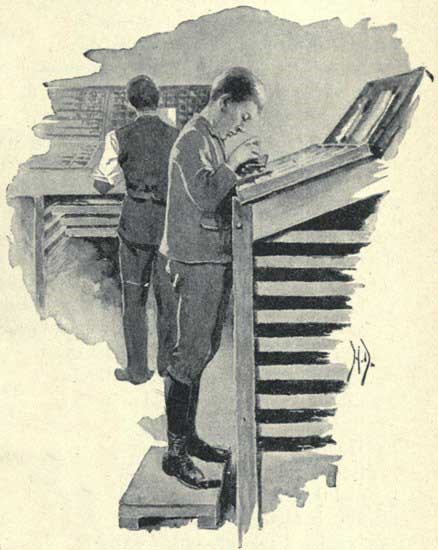

TYPE-SETTING AT THE AVENUE C WORKING BOYS’ CLUB.

The carpenter-shop of the Avenue C Working Boys’ Club has been a distinct success for several seasons. The work done by the boys after a few months’ instruction compares often well with that of the majority of apprentices who have been years learning the trade in the regular way. The shop is fitted out with benches and all the necessary tools. A class in type-setting vies with the young carpenters in excellence of workmanship and devotion to business. The printers have ambitious designs upon the reading public. They intend to start a monthly “organ” of their club, an experiment that was tried once but frustrated by a change of base from Twenty-first Street to the present quarters at No. 650 East Fourteenth Street. The club grew up under the eaves of St. George’s Church eight years ago, and was known by the name of the St. George’s Boys’ Club after it had been forced to move away to make room for the erection of the Parish House. Some of the boys work in the daytime at the trades which they are taught at the club in the evening, and the instruction thus received has helped them to earn better salaries in many cases. One of the managers keeps a bank account for those who can save money and want to invest it, and more than one of them has a snug little sum to his credit. There are fifty boys in each class, and always plenty waiting for vacancies to occur. The best pupils receive medals at the end of the year, and once every summer the managers, who are young men of position and character, take them out in the country for an outing, and are boys with them in their games and in their delight over the new sights they see there.

Mr. Wendell tells of one of these trips down to see “Buffalo Bill” on Staten Island. There was a big crowd of excursionists on the boat going down, and the captain took a fatherly interest in the boys, who were gathered together in the bow of the boat, quiet as lambs. The return trip was not so peaceful, though the captain good-naturedly delayed the boat beyond the starting time for fear some of “our boys” would get left, as indeed proved to be the fate of several. But by the time this was discovered it was no longer a source of regret to him. The Indians and the bucking broncos had made the boys restless. They stood around the brass band, and one of them attempted to relieve his pent-up feelings by sticking a button into the big trombone, with the effect of nearly strangling the stout gentleman who was playing on it. The enraged musician made a wild dive for the boy, who dodged around the smokestack and caught up a chair to defend himself with. In a moment a first-class riot was in progress, chairs flying, the band men swearing, and the boys yelling like Comanches. When quiet had been finally restored, the boys banished to the after-deck, and the button fished out of the trombone, the perspiring captain swore with a round oath that he “wouldn’t take those d–d boys down to Staten Island again for ten dollars a head.”

The trade-school feature of the Working Boys’ Club may soon be reproduced in the Calvary Parish Boys’ Club in East Twenty-third Street. They have already a useful type-setting class there, and they have that which their neighbors in Fourteenth Street have yet to get: their own handsome building, bought for the club by wealthy members of Calvary Church, in which it had its birth four years ago. More than that, they have a gymnasium that is the chief attraction of all that neighborhood, particularly the boxing-gloves in it. There were some serious doubts about these, and long and grave discussion before they were added to the general outfit. The street was rather too partial to fisticuffs, it was thought, and there were too many outstanding grudges among the boys to make their introduction safe. However, another view prevailed and the choice proved to be a wise one. The gloves are popular—very, and under the firm management of the experienced superintendent, who knows where to draw the safe line, the boys work off their superabundant spirits and sundry other little accounts very successfully in their nightly bouts. The feeling of fellowship and neighborly interest thus encouraged has even led to the establishment of a mutual benefit fund, through which the boys help each other in sickness or distress, and which they manage themselves, electing their own officers.

For anyone who knows the boys of the East Side it is not hard to understand that the Calvary Parish Boys’ Club has registered more than twenty-eight thousand callers since it was opened, only four years ago. It has four hundred enrolled members, who pay monthly dues of ten cents, so that they may feel that the club is theirs by right, not by charity. Though church and temperance stood at the cradle of the club—it was organized at a meeting of the Calvary branch of the Church Temperance Society—there is no preaching to the boys. The only sermons they hear at the club are the sermons of brotherly love and kindness, which the cheerful rooms, the games, the books, and the gymnasium—even the boxing-gloves—preach to them every night, and which the contrast of it all with the street, that was their all only a little while ago, is not apt to let them forget.