полная версия

полная версияThe Children of the Poor

“Among our grown girls,” she adds, “we have teachers, governesses, dressmakers, milliners, trained nurses, machine operators, hand sewers, embroiderers, designers for embroidering, servants in families, saleswomen, book-keepers, typewriters, candy packers, bric-à-brac packers, bank-note printers, silk winders, button makers, box makers, hairdressers, and fur sewers. Among our boys are book-keepers, workers in stained glass, painters, printers, lithographers, salesmen in wholesale houses, as well as in many of our largest retail stores, typewriters, stenographers, commission merchants, farmers, electricians, ship carpenters, foremen in factories, grocers, carpet designers, silver engravers, metal burnishers, carpenters, masons, carpet weavers, plumbers, stone workers, cigar makers, and cigar packers. Only one of our boys, so far as we can learn, ever sold liquor, and he has given it up.”

Not a few of these, without a doubt, got the first inkling of their trade in the class where they learned to read. The curriculum of the Industrial Schools is comprehensive. The nationality of the pupils makes little or no difference in it. The start, as often as is necessary, is made with an object lesson—soap and water being the elements, and the child the object. As in the kindergarten, the alphabet comes second on the list. Then follow lessons in sewing, cooking, darning, mat-weaving, pasting, and dressmaking for the girls, and in carpentry, wood carving, drawing, printing, and like practical “branches” for the boys, not a few of whom develop surprising cleverness at this or that kind of work. The system is continually expanding. There are schools yet that have not the necessary facilities for classes in manual training, but as the importance of the subject is getting to be more clearly understood, and interest in the subject grows, new “shops” are being constantly opened and other occupations found for the children. Even where the school quarters are most pinched and inadequate, a shift is made to give the children work to do that will teach them habits of industry and precision as the all-important lesson to be learned there. In some of the Industrial Schools the boys learn to cook with the girls, and in the West Side Italian School an attempt to teach them to patch and sew buttons on their own jackets resulted last year in their making their own shirts, and making them well, too. Perhaps the possession of the shirt as a reward for making it acted as a stimulus. The teacher thought so, and she was probably right, for more than one of them had never owned a whole shirt before, let alone a clean one. A heap can be done with the children by appealing to their proper pride—much more than many might think, judging hastily from their rags. Call it vanity—if it is a kind of vanity that can be made a stepping-stone to the rescue of the child, it is worth laying hold of. It was distinct evidence that civilization and the nineteenth century had invaded Lewis Street, when a class of Hungarian boys in the American Female Guardian Society’s school in that thoroughfare earned the name of the “neck-tie class” by adopting that article of apparel in a body. None of them had ever known collar or necktie before.

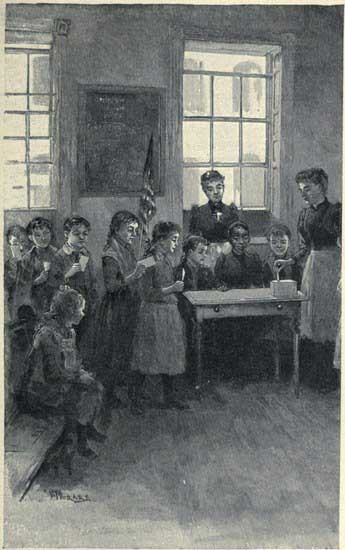

THE FIRST PATRIOTIC ELECTION IN THE BEACH STREET INDUSTRIAL SCHOOL—PARLOR IN JOHN ERICSSON’S OLD HOUSE.

It is the practice to let the girls have what garments they make, from material, old or new, furnished by the school, and thus a good many of the pupils in the Industrial Schools are supplied with decent clothing. In the winter especially, some of them need it sadly. In the Italian school of which I just spoke, one of the teachers found a little girl of six years crying softly in her seat on a bitter cold day. She had just come in from the street. In answer to the question what ailed her, she sobbed out, “I’se so cold.” And no wonder. Beside a worn old undergarment, all the clothing upon her shivering little body was a thin calico dress. The soles were worn off her shoes, and toes and heels stuck out. It seemed a marvel that she had come through the snow and ice as she had, without having her feet frozen.

Naturally the teacher would follow such a child into her home and there endeavor to clinch the efforts begun for its reclamation in the school. It is the very core and kernel of the Society’s purpose not to let go of the children of whom once it has laid hold, and to this end it employs its own physicians to treat those who are sick, and to canvass the poorest tenements in the summer months, on the plan pursued by the Health Department. Last year these doctors, ten in number, treated 1,578 sick children and 174 mothers. Into every sick-room and many wretched hovels, daily bouquets of sweet flowers found their way too, visible tokens of a sympathy and love in the world beyond—seemingly so far beyond the poverty and misery of the slum—that had thought and care even for such as they. Perhaps in the final reckoning these flowers, that came from friends far and near, will have a story to tell that will outweigh all the rest. It may be an “impracticable notion,” as I have sometimes been told by hard-headed men of business; but it is not always the hard head that scores in work among the poor. The language of the heart is a tongue that is understood in the poorest tenements where the English speech is scarcely comprehended and rated little above the hovels in which the immigrants are receiving their first lessons in the dignity of American citizenship.

Very lately a unique exercise has been added to the course in these schools, that lays hold of the very marrow of the problem with which they deal. It is called “saluting the flag,” and originated with Colonel George T. Balch, of the Board of Education, who conceived the idea of instilling patriotism into the little future citizens of the Republic in doses to suit their childish minds. To talk about the Union, of which most of them had but the vaguest notion, or of the duty of the citizen, of which they had no notion at all, was nonsense. In the flag it was all found embodied in a central idea which they could grasp. In the morning the star-spangled banner was brought into the school, and the children were taught to salute it with patriotic words. Then the best scholar of the day before was called out of the ranks, and it was given to him or her to keep for the day. The thing took at once and was a tremendous success.

Then was evolved the plan of letting the children decide for themselves whether or not they would so salute the flag as a voluntary offering, while incidentally instructing them in the duties of the voter at a time when voting was the one topic of general interest. Ballot-boxes were set up in the schools on the day before the last general election (1891). The children had been furnished with ballots for and against the flag the week before, and told to take them home to their parents and talk it over with them, a very apt reminder to those who were naturalized citizens of their own duties, then pressing. On the face of the ballot was the question to be decided: “Shall the school salute the Nation’s flag every day at the morning exercises?” with a Yes and a No, to be crossed out as the voter wished. On its back was printed a Voter’s A, B, C, in large plain type, easy to read:

“This country in which I live, and which is my country, is called a Republic. In a Republic, the people govern. The people who govern are called citizens. I am one of the people and a little citizen.

“The way the citizens govern is, either by voting for the person whom they want to represent them, or who will say what the people want him to say—or by voting for that thing they would like to do, or against that thing which they do not want to do.

“The Citizen who votes is called a voter or an elector, and the right of voting is called the suffrage. The voter puts on a piece of paper what he wants. The piece of paper is called a Ballot. This Piece of Paper is my Ballot.

“The right of a Citizen to vote; the right to say what the citizen thinks is best for himself and all the rest of the people; the right to say who shall govern us and make laws for us, is a Great Privilege, a Sacred Trust, A very great Responsibility, which I must learn to exercise conscientiously, and to the best of my knowledge and ability, as a little Citizen of this great American Republic.”

On Monday the children cast their votes in the Society’s twenty-one Industrial Schools, with all the solemnity of a regular election and with as much of its simple machinery as was practicable. Eighty-two per cent. of the whole number of enrolled scholars turned out for the occasion, and of the 4,306 votes cast, 88, not quite two per cent., voted against the flag. Some of these, probably the majority, voted No under a misapprehension, but there were a few exceptions. One little Irishman, in the Mott Street school, came without his ballot. “The old man tored it up,” he reported. In the East Seventy-third Street school five Bohemians of tender years set themselves down as opposed to the scheme of making Americans of them. Only one, a little girl, gave her reason. She brought her own flag to school: “I vote for that,” she said, sturdily, and the teacher wisely recorded her vote and let her keep the banner.

I happened to witness the election in the Beach Street school, where the children are nearly all Italians. The minority elements were, however, represented on the board of election inspectors by a colored girl and a little Irish miss, who did not seem in the least abashed by the fact that they were nearly the only representatives of their people in the school. The tremendous show of dignity with which they took their seats at the poll was most impressive. As a lesson in practical politics, the occasion had its own humor. It was clear that the negress was most impressed with the solemnity of the occasion, and the Irish girl with its practical opportunities. The Italian’s disposition to grin and frolic, even in her new and solemn character, betrayed the ease with which she would, were it real politics, become the game of her Celtic colleague. When it was all over they canvassed the vote with all the solemnity befitting the occasion, signed together a certificate stating the result, and handed it over to the principal sealed in a manner to defeat any attempt at fraud. Then the school sang Santa Lucia, a sweet Neapolitan ballad. It was amusing to hear the colored girl and the half-dozen little Irish children sing right along with the rest the Italian words, of which they did not understand one. They had learned them from hearing them sung by the others, and rolled them out just as loudly, if not as sweetly, as they.

THE BOARD OF ELECTION INSPECTORS IN THE BEACH STREET SCHOOL.

The first patriotic election in the Fifth Ward Industrial School was held on historic ground. The house it occupies was John Ericsson’s until his death, and there he planned nearly all his great inventions, among them one that helped save the flag for which the children voted that day. The children have lived faithfully up to their pledge. Every morning sees the flag carried to the principal’s desk and all the little ones, rising at the stroke of the bell, say with one voice: “We turn to our flag as the sunflower turns to the sun!” One bell, and every brown right fist is raised to the brow, as in military salute: “We give our heads!” Another stroke, and the grimy little hands are laid on as many hearts: “and our hearts!” Then with a shout that can be heard around the corner: “– to our country! One country, one language, one flag!” No one can hear it and doubt that the children mean every word and will not be apt to forget that lesson soon.

The Industrial School has found a way of dealing with even the truants, of whom it gets more than its share, and the success of it is suggestive. As stated by the teacher in the West Eighteenth Street school who found it out, it is very simple: “I tell them, if they want to play truant to come to me and I will excuse them for the day, and give them a note so that if the truant officer sees them it will be all right.” She adds that “only one boy ever availed himself of that privilege.” The other boys with few exceptions became interested, as one would expect, and came to school regularly. It was the old story of the boys in the Juvenile Asylum who could be trusted to do guard duty in the grounds when put upon their honor, but the moment they were locked up for the night risked their necks to escape by climbing out of the third-story windows.

But when it has cheated the street and made of the truant a steady scholar, the work of the Industrial School is not all done. Next, it hands him over to the Public School, clothed and in his right mind, if his time to go to work has not yet come. Last year the thirty-three Industrial Schools of the Children’s Aid Society and the American Female Guardian Society thus dismissed nearly eleven hundred children who, but for their intervention, might never have reached that goal. That their charity had not been allowed to corrupt the children may be inferred from the statement that, with an average daily attendance of 4,348 in the Children’s Aid Society’s Schools, 1,729 children were depositors in the School Savings Banks to the aggregate amount of about $800—a very large sum for them—and this in the face of the fact, recorded on the school register, that 938 of the lot came from homes where drunkenness and poverty went hand in hand. It is not in the plan of the Industrial School to make paupers, but to develop to the utmost the kernel of self-help that is the one useful legacy of the street. The child’s individuality is preserved at any cost. Even the clothes that are given to the poorest in exchange for their rags are of different cut and color, made so with this one end in view. The distressing “institution look” is wholly absent from these schools, and one of the great stumbling-blocks of charity administered at wholesale is thus avoided.

The night schools are for the boys and girls already enlisted in the treadmill, and who must pick up what learning they can in their off hours. Together with the day-schools they footed up a total enrolment of nearly ten thousand children whom this Society reached in 1891. Upon the basis of the average daily attendance, the cost of their education to the community, which supported the charity, was $24.53 for each child. The cost of sheltering, feeding, and teaching 11,770 boys and girls in the Society’s six lodging-houses was $32.76 for each; the expense of sending 2,825 children to farm-homes $9.96 for each. The average cost per year for each prisoner in the Tombs is $107.75, and for every child maintained in an Asylum, or in the poor-house, nearly $140.21

“One of our great difficulties,” says the Secretary of the Children’s Aid Society, in a recent statement of the Society’s aims and purposes, echoing an old grievance, “is with the large boys of the city. There seems to be no place for them in the world as it is. They have grown up in it without any training but that in street trades. The trades unions have kept them from being apprenticed. They are soon too large for street occupations, and are unable to compete with the small boys. They are too old for our lodging-houses. We know not what to do with them. Some succeed well on Western farms, but they are usually disliked by their employers because they change places soon; and their occasional offences and disposition to move about have given us more trouble in the West than any other one thing. Very few people are willing to bear with them, even though a little patience will sometimes bring out excellent qualities in them.” They are the boys for whom the street and the saloon have use that shall speedily fashion of their “excellent qualities” a lash to sting the community’s purse, if not its conscience, with the memory of its neglect. As 107.75 is to 24.53, or 140 to 9.96, so will be the smart of it compared with the burden of patience that would have turned the scales the other way, to put the matter in a light where the hard-headed man of business can see it without an effort.

There is at least one man of that kind in New York who has seen and understood it to some purpose. His name is Richard T. Auchmuty, and he is by profession an architect. In that capacity he has had opportunity enough of observing how the virtual exclusion of the New York boy from the trades worked to his harm, and he started for his relief an Industrial School that deserves to be ranked among the great benefactions of our day, even more for its power to set people to thinking than for the direct benefit it confers upon the boy, great as that is. Once it comes to be thoroughly understood that a chance to learn his father’s honest trade is denied the New York boy by a foreign conspiracy, because he is an American lad and cannot be trusted to do its bidding, it is inconceivable that an end should not be put in quick order to this astounding abuse. This thing is exactly what is being done in New York now by the consent of its citizens, who without a protest read in the newspapers that a trades-union, one of the largest and strongest in the building trades, has decreed that for two years from a fixed date no apprentice shall be admitted to that trade in New York—decreed, with the consent and connivance of subservient employers, that so many lads who might have become useful mechanics shall grow up tramps and loafers; decreed that a system of robbery of the American mechanic shall go on by which it has come to pass that out of twenty-three millions of dollars paid in a year to the building trades in this city barely six millions are grudgingly accorded the native worker. There is no decree to exclude the mechanic from abroad. He may come and go—and go he does, in shoals, to his home across the sea at the end of each season, with its profits—under the scheme of international comradeship that excludes only the American workman and his boy. I have talked with some of the most intelligent of the labor leaders, men well known all over the land, to find out if there were any defence to be made for this that I was not aware of, but have got nothing but evasion and sophistries about the “protection of labor” for my answer. A protection, indeed, that has nearly resulted already in the practical extinction of the American mechanic, the best and cleverest in the world, in America’s chief city, at the bidding of the Walking Delegate.

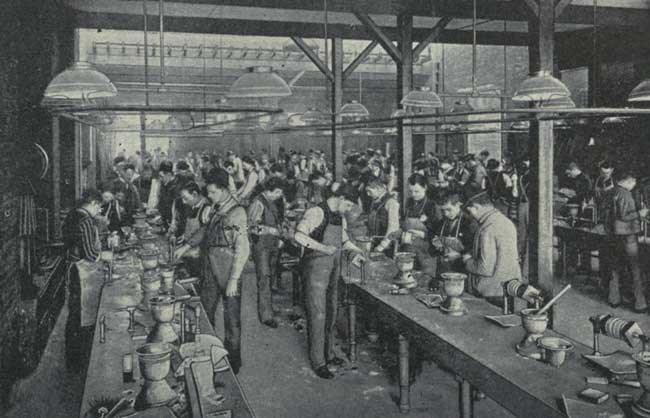

THE PLUMBING SHOP IN THE NEW YORK TRADE SCHOOLS.

Even to Colonel Auchmuty’s Industrial School this persecution has been extended in a persistent attempt for years to taboo its graduates. In spite of it, the New York Trade Schools open their twelfth season this winter with six hundred scholars and more, in place of the thirty who sat in the first class eleven years ago. The community’s better sense is coming to the rescue, and the opposition to the school is wearing off. In the spring as many hundred young plasterers, printers, tailors, plumbers, stone-cutters, bricklayers, carpenters, and blacksmiths will go forth capable mechanics, and with their self-respect unimpaired by the associations of the shop and the saloon under the old apprentice system. In this one respect the trades union may have done them a service it did not intend. Colonel Auchmuty’s school has demonstrated what it amounts to by furnishing from among its young men the bricklayers for more than as many handsome buildings in New York as there were pupils in its first class. When a committee of master builders came on from Philadelphia to see what their work was like, the report it brought back was that it looked as if the builders had put their hearts in it, and a trade-school was forthwith established in that city. Of that, too, Colonel Auchmuty paid the way from the start.

His wealth has kept the New York school above water since it was started; but this winter a benevolent millionaire, Mr. J. Pierpont Morgan, for whom wealth has other and greater responsibilities than that of ministering to his own comfort, has endowed it with half a million dollars, and Mrs. Auchmuty has added a hundred thousand with the land on First Avenue between Sixty-seventh and Sixty-eighth Streets upon which the school stands, so that it starts out with an endowment sufficient to insure its future. The charges for tuition in the day and evening classes have never been much more than nominal, but these may now, perhaps, be reduced even further to allow the “excellent qualities” of the big boys, of whom the reformer despairs, to be put to their proper use without robbing them of the best of all, their self-respect. Then the gage will have been thrown to the street in good earnest, and the Walking Delegate’s day will be nearly spent.

CHAPTER XIII.

THE BOYS’ CLUBS

BUT it is by the boys’ club that the street is hardest hit. In the fight for the lad it is that which knocks out the “gang,” and with its own weapon—the weapon of organization. That this has seemed heretofore so little understood, even by some who have wielded the weapon valiantly, is to me the strongest argument for the University Settlement plan, which sends those who would be of service to the poor out to live among them, to study their ways and their needs. Very soon they discover why the gang has such a grip on the boy. It is because it responds to a real need of his nature. The distinguishing characteristic of the American city boy is his genius for organization. Whether it be in the air, in the soil, or in an aptitude for self-government that springs naturally from the street, where every little heathen is a law unto himself—one of them surely, for the children of foreigners, who never learn to speak the language in which their sons vote, exhibit it, if anything, more plainly than the native-born—he has it, undeniably. Unbridled, allowed to run riot, it results in the gang. Thwarted, it defeats all attempts to manage the boy. Accepted as a friend, an ally, it is the indispensable key to his nature in all efforts to reclaim him en bloc. Individuals may require different methods of treatment. To the boys as a class the club is the pass-key.

There are many boys’ clubs in New York now, and room for more. Some have had great success; a few have failed. I venture the guess that the real failure in a good many instances—most of them perhaps—was the failure to trust the boys to rule themselves. I say rule. Rule there must be; boss rule at that. That is the kind their fathers own, the fashion of the slums. It is a case of rule or ruin, order or anarchy. To let the boys have full swing would merely be to invite the street in to take charge of the house, and only trouble would come of it. But the boss must be a benevolent and very politic despot. The boy must have a fair chance. To enlist him heart and soul, the opportunity must be given him to show that he can rule himself. And he will show it. He must be allowed to choose his own leaders. His freedom of speech must not be abridged in debate by any rule but that of parliamentary law. Ten to one he will not abuse it, but will enforce that rule and submit to it as scrupulously as the most punctilious of his elders. Let him be sure that his right to self-government will not be interfered with, and he will voluntarily give up the street and his gang. Three boys’ clubs had been started by the ladies of the College Settlement, on the principle of non-interference within the few and simple rules of the house. The boys wrote their own laws and maintained order with success. The street looked on, observant. To the policeman it had opposed secret hostility or open war. But a social order with the policeman eliminated was something worthy of approval. Its offer of surrender was brought in form by a committee representing the “Pleasure Club” in the toughest block of the neighborhood. “We will change and have your kind of a club,” was its message. Thus the fourth boys’ club of the Settlement was launched.

They have not all had so peaceful a beginning. Storm and stress of weather have ushered in most of them. Each new one has cost something for window-glass, and the mud of the neighborhood has had its inning before it was forced to abdicate in favor of the club. It was so with the first that was started, fourteen years ago, in Tompkins Square, that was then pretty much all mud and given over to anarchy and disorder. In fact, it was the mud that started the club. It flew so thick about the Wilson Mission, and bespattered those who went out and in so freely that on a particularly boisterous night the good missionary’s wife decided that something must be done. She did not send for a policeman. She had tried that before, but the relief he brought lasted only while he was in sight. She went out and confronted the mob herself. When it had yelled itself hoarse at her, she sweetly asked it in to have some coffee and cakes. The mob stared, breathless. Coffee and cakes for stones and mud! This was the Gospel in a shape that was new and bewildering to Tompkins Square. The boys took counsel among themselves. Visions of a big policeman behind the door troubled the timid; but the more courageous were in favor of taking chances. When they had sidled through the open door and no yell of distress had betrayed treason within, the rest followed to find the coffee and the cakes a solid and reassuring fact. No awkward questions were asked about the broken windows, and the boys came out voting the “missionary people” trumps, with a tinge of remorse, let us hope, for the reception they had given them. There was no more mud-slinging after that, but the boys fell naturally into neighborly ways with the house and its occupants, and the proposition to be allowed to come in and “play games,” came from them when the occasional misunderstandings with the policeman on the post made the street a ticklish play-ground. They were let in, and when certain good people heard of what was going on in Tompkins Square, they sent down chairs and tables and games, so that they might be made to feel at home. Thus kindness conquered the street, and that winter was founded the first boys’ club here, or, for aught I know, anywhere. It is still the Boys’ Club of St. Mark’s Place, and has grown more popular with the boys as the years have passed. The record of last winter’s doings over there show no less than 2,757 boys on its roll of membership. The total attendance for the year was 42,118, and the nightly average 218 boys, everyone of whom, but for the coffee and cakes of that memorable night, might have been in the streets slinging mud.