полная версия

полная версияThe Children of the Poor

June 15, 1880. James S–, aged fourteen years, English; orphan; goes West with J. P. Brace.

Placed with J. R–, Neosha Rapids, Kan. January 26, 1880, James writes that he gets along pleasantly; wrote to him; twenty-sixth annual report sent August 4th. July 14, 1880, Mr. and Mrs. R– write that James is impudent and tries them greatly. Wrote to him August 17, 1880; wrote again October 15th. October 21, 1880, Mr. R– writes that they could not possibly get along with James and placed him with Mr. G. H–, about five miles from his house. Mr. H– is a good man and has a handsome property. Wrote to James March 8, 1881. May 1, 1883, has left his place and has engaged to work for Mr. H–, of Hartford. James seems to be a pretty wild boy, and the probability is he will turn out badly; is very profane and has a violent temper. April 17, 1887, Mrs. Lyman Fry writes James was crushed to death in Kansas City, where he was employed as brakeman on a freight train.

October 16, 1889.—The above is a mistake. James calls to-day at the office and says that after I saw him he turned over a new leaf, and has made a pretty good character for himself. Has worked steadily and has many friends in Emporia. Has been here three days and wants to look up his friends. Is grateful for having been sent West.”

So James came out right after all, and all his sins are forgiven. He was a fair sample of those who have troubled the Society’s managers most, occasionally brought undeserved reproach upon them, but in the end given them the sweet joy of knowing that their faith and trust were not put to shame. Many pages in the ledgers shine with testimony to that. I shall mention but a single case, the one to which I alluded in the introduction to the story of the Industrial Schools. Andrew H. Burke was taken by the Society’s agents from the nursery at Randall’s Island, thirty-three years ago, with a number of other boys, and sent out to Nobleville, Ind. They heard from him in St. Mark’s Place as joining the Sons of Temperance, then as going to the war, a drummer boy; next of his going to college with a determination “to be somebody in the world.” He carried his point. That boy is now the Governor of North Dakota. Last winter he wrote to his kind friends, full of loyalty and gratitude, this message for the poor children of New York:

“To the boys now under your charge please convey my best wishes, and that I hope that their pathways in life will be those of morality, of honor, of health, and industry. With these four attributes as a guidance and incentive, I can bespeak for them an honorable and happy and successful life. The goal is for them as well as for the rich man’s son. They must learn to labor and to wait, for ‘all things come to him who waits.’ Many times will the road be rugged, winding, and long, and the sky overcast with ominous clouds. Still, it will not do to fall by the wayside and give up. If one does, the battle of life will be lost.

“Tell the boys I am proud to have had as humble a beginning in life as they, and that I believe it has been my salvation. I hope my success in life, if it can be so termed, will be an incentive to them to struggle for a respectable recognition among their fellow-men. In this country family name cuts but little figure. It is the character of the man that wins recognition, hence I would urge them to build carefully and consistently for the future.”

The bigger boys do not always give so good an account of themselves. I have already spoken of the difficulty besetting the Society’s efforts to deal with that end of the problem. The street in their case has had the first inning, and the battle is hard, often doubtful. Sometimes it is lost. These are rarely sent West, early consignments of them having stirred up a good deal of trouble there. They go South, where they seem to have more patience with them. “The people there,” said an old agent of the Society to me, with an enthusiasm that was fairly contagious, “are the most generous, kind-hearted people in the world. And they are more easy going. If a boy turns out badly, steals and runs away perhaps, a letter comes, asking not for retaliation or upbraiding us for letting him come, but hoping that he will do better, expressing sorrow and concern, and ending usually with the big-hearted request that we send them another in his place.” And another comes, and, ten to one, does better. What lad is there whose wayward spirit such kindness would not conquer in the end?24

These bigger boys come usually out of the Society’s lodging-houses for homeless children. Of these I spoke so fully in the account of the Street Arab in “How the Other Half Lives,” that I shall not here enter into any detailed description of them. There are six, one for girls in East Twelfth Street, lately moved from St. Mark’s Place, and five for boys. The oldest and best known of these is the Newsboys’ lodging-house in Duane Street, now called the Brace Memorial Lodging-house for Boys. The others are the East Side house in East Broadway, the Tompkins Square house, the West Side house at Seventh Avenue and Thirty-second Street, and the lodging-house at Forty-fourth Street and Second Avenue. A list of the builders’ names emphasizes what I said a while ago about the unostentatious charity of rich New Yorkers. I have never seen them published anywhere except in the Society’s reports, but they make good and instructive reading, and here they are in the order in which I gave the houses they built, beginning with the one on East Broadway: Miss Catharine L. Wolfe, Mrs. Robert L. Stuart, John Jacob Astor, Morris K. Jesup. The girls’ home in East Twelfth Street, just completed, was built as a memorial to Miss Elizabeth Davenport Wheeler by her family, and is to be known as the Elizabeth Home. The list might be greatly extended by including the twenty-one Industrial Schools, which are in fact links in the same great chain; but that is not to the present purpose, and probably I should not be thanked for doing it. I have already transgressed enough. The wealth that seeks its responsibilities among the outcast children in this city, is of the kind that prefers that it should remain unidentified and unheralded to the world in connection with its benefactions.

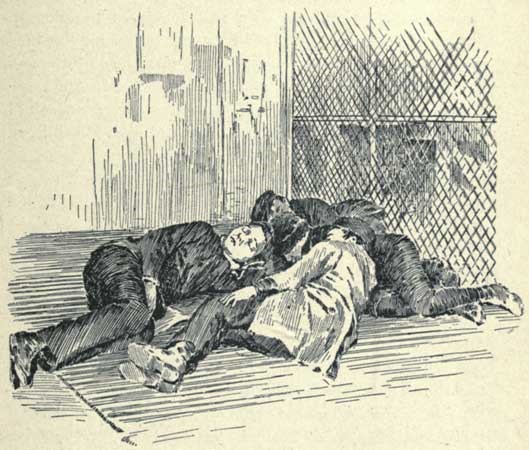

It is in these lodging-houses that one may study the homelessness that mocks the miles of brick walls which enclose New York’s tenements, but not its homes. Only with special opportunities is it nowadays possible to study it anywhere else in New York. One may still hunt up by night waifs who make their beds in alleys and cellars and abandoned sheds. This last winter two stable fires that broke out in the middle of the night routed out little colonies of boys, who slept in the hay and probably set it on fire. But one no longer stumbles over homeless waifs in the street gutters. One has to hunt for them and to know where. The “cruelty man” knows and hunts them so assiduously that the game is getting scarcer every day. The doors of the lodging-houses stand open day and night, offering shelter upon terms no cold or hungry lad would reject: six cents for breakfast and supper, six for a clean bed. They are not pauper barracks, and he is expected to pay; but he can have trust if his pockets are empty, as they probably are, and even a bootblack’s kit or an armful of papers to start him in business, if need be. The only conditions are that he shall wash and not swear, and attend evening school when his work is done. It is not possible to-day that an outcast child should long remain supperless and without shelter in New York, unless he prefers to take his chances with the rats of the gutter. Such children there are, but they are no longer often met. The winter’s cold drives even them to cover and to accept the terms they rejected in more hospitable seasons. Even the “dock-rat” is human.

It seems a marvel that he is, sometimes, when one hears the story of what drove him to the street. Drunkenness and brutality at home helped the tenement do it, half the time. It drove his sister out to a life of shame, too, as likely as not. I have talked with a good many of the boys, trying to find out, and heard some yarns and some stories that were true. In seven cases out of ten, of those who had homes to go to, it was that, when we got down to hard pan. A drunken father or mother made the street preferable to the house, and to the street they went.25 In other cases death, perhaps, had broken up the family and thrown the boys upon the world. That was the story of one of the boys I tried to photograph at a quiet game of “craps” (see picture on page 122) in the hallway of the Duane Street lodging-house—James Brady. Father and mother had both died two months after they came here from Ireland, and he went forth from the tenement alone and without a friend, but not without courage. He just walked on until he stumbled on the lodging-house, and fell into a job of selling papers. James, at the age of sixteen, was being initiated into the mysteries of the alphabet in the evening school. He was not sure that he liked it. The German boy who took a hand in the game, and who made his grub and bed money, when he was lucky, by picking up junk, had just such a career. The third, the bootblack, gave his reasons briefly for running away from his Philadelphia home: “Me muther wuz all the time hittin’ me when I cum in the house, so I cum away.” So did a German boy I met there, if for a slightly different reason. He was fresh from over the sea, and had not yet learned a word of English. In his own tongue he told why he came. His father sent him to a gymnasium, but the Latin was “zu schwer” for him, and “der Herr Papa sagt heraus!” He was evidently a boy of good family, but slow. His father could have taken no better course, certainly, to cure him of that defect, if he did not mind the danger of it.

There are always some whom nobody owns. Boys who come from a distance perhaps, and are cast up in our streets with all the other drift that sets toward the city’s maelstrom. But the great mass were born of the maelstrom and ground by it into what they are. Of fourteen lads rounded up by the officers of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children one night this past summer, in the alleys and byways down about the printing offices, where they have their run, two were from Brooklyn, one a runaway from a good home in White Plains, and the rest from the tenements of New York. Only one was really without home or friends. That was perhaps an unusually—I was going to say good showing; but I do not know that it can be called a good showing that ten boys who had homes to go to should prefer to sleep out in the street. The boy who has none would have no other choice until someone picked him up and took him in. The record of the 84,318 children that have been sent to Western homes in thirty-nine years show that 17,383 of them had both parents living, and therefore presumably homes, such as they were; 5,892 only the father, and 11,954 the mother, living; 39,406 had neither father nor mother. The rest either did not know, or did not tell. That again includes an earlier period when the streets were full of vagrants without home-ties, so that the statement, as applied to to-day, errs on the other side. The truth lies between the two extremes. Four-fifths, perhaps, are outcasts, the rest homeless waifs.

The great mass, for instance, of the newsboys who cry their “extrees” in the streets by day, and whom one meets in the Duane Street lodging-house or in Theatre Alley and about the Post-office by night, are children with homes who thus contribute to the family earnings, and sleep out, if they do, because they have either not sold their papers or gambled away the money at “craps,” and are afraid to go home. It was for such a reason little Giuseppe Margalto and his chum made their bed in the ventilating chute at the Post-office on the night General Sherman died, and were caught by the fire that broke out in the mail-room toward midnight. Giuseppe was burned to death; the other escaped to bring the news to the dark Crosby Street alley in which he had lived. Giuseppe did not die his cruel death in vain. A much stricter watch has been kept since upon the boys, and they are no longer allowed to sleep in many places to which they formerly had access.

A bed in the street, in an odd box or corner, is good enough for the ragamuffin who thinks the latitude of his tenement unhealthy, when the weather is warm. It is cooler there, too, and it costs nothing, if one can keep out of the reach of the policeman. It is no new experience to the boy. Half the tenement population, men, women, and children, sleep out of doors, in streets and yards, on the roof, or on the fire-escape, from May to October. In winter the boys can curl themselves up on the steam-pipes in the newspaper offices that open their doors after midnight on secret purpose to let them in. When these fail, there is still the lodging-house as a last resort. To the lad whom ill-treatment or misfortune drove to the street it is always a friend. To the chronic vagrant it has several drawbacks: the school, the wash, the enforced tax for the supper and the bed, that cuts down the allowance for “craps,” his all-absorbing passion, and finally the occasional inconvenient habit of mothers and fathers to come looking there for their missing boys. The police send them there, and sometimes they take the trouble to call when the boys have gone to bed, taking them at what they consider a mean disadvantage. However, most of them do not trouble themselves to that extent. They let the strap hang idle till the boy comes back, if he ever does.

2 A.M. IN THE DELIVERY ROOM IN THE “SUN” OFFICE.

Last February Harry Quill, aged fifteen, disappeared from the tenement No. 45 Washington Street, and though he was not heard of again for many weeks, his people never bothered the police. Not until his dead body was fished up from the air-shaft at the bottom of which it had lain two whole months, was his disappearance explained. But the full explanation came only the other day, in September, when one of his playmates was arrested for throwing him down and confessed to doing it. Harry was drunk, he said, and attacked him on the roof with a knife. In the struggle he threw him into the air-shaft. Fifteen years old, and fighting drunk! The mere statement sheds a stronger light on the sources of child vagabondage in our city than I could do, were I to fill the rest of my book with an enumeration of them.

However, it is a good deal oftener the father who gets drunk than the boy. Not all, nor even a majority, of the boys one meets at the lodging-houses are of that stamp. If they were, they would not be there long. They have their faults, and the code of morals proclaimed by the little newsboys, for instance, is not always in absolute harmony with that generally adopted by civilized society. But even they have virtues quite as conspicuous. They are honest after their fashion, and tremendously impartial in a fight. They are bound to see fair play, if they all have to take a hand. It generally ends that way. A good many of them—the great majority in all the other lodging-houses but that in Duane Street—work steadily in shops and factories, making their home there because it is the best they have, and because there they are among friends they know. Two little brothers, John and Willie, attracted my attention in the Newsboys’ Lodging-house by the sturdy way in which they held together, back to back, against the world, as it were. Willie was thirteen and John eleven years old. Their story was simple and soon told. Their mother died, and their father, who worked in a gas-house, broke up the household, unable to maintain it. The boys went out to shift for themselves, while he made his home in a Bowery lodging-house. The oldest of the brothers was then earning three dollars a week in a factory; the younger was selling newspapers, and making out. The day I first saw him he came in from his route early—it was raining hard—to get dry trousers out for his brother against the time he should be home from the factory. There was no doubt the two would hew their way through the world together. The right stuff was in them, as in the two other lads, also brothers, I found in the Tompkins Square lodging-house. Their parents had both died, leaving them to care for a palsied sister and a little brother. They sent the little one to school, and went to work for the sister. Their combined earnings at the shop were just enough to support her and one of the brothers who stayed with her. The other went to the lodging-house, where he could live for eighteen cents a day, turning the rest of his earnings into the family fund. With this view of these homeless lads, the one who goes much among them is not surprised to hear of their clubbing together, as they did in the Seventh Avenue lodging-house, to fit out a little ragamuffin, who was brought in shivering from the street, with a suit of clothes. There was not one in the crowd that chipped in who had a whole coat to his back.

BUFFALO.

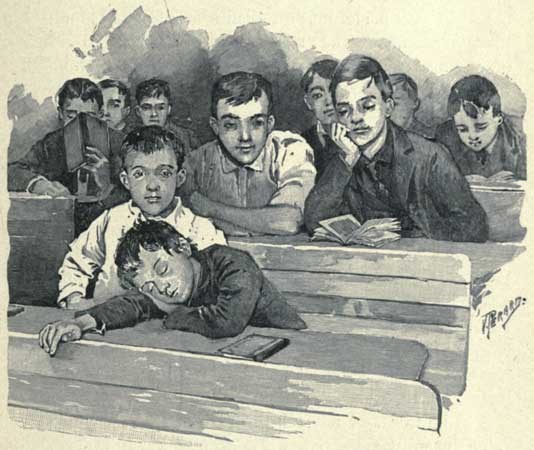

It was in this lodging-house I first saw Buffalo. He was presented to me the night I took the picture of my little vegetable-peddling friend, Edward, asleep on the front bench in evening school. Edward was nine years old and an orphan, but hard at work every day earning his own living by shouting from a pedlar’s cart. He could not be made to sit for his picture, and I took him at a disadvantage—in a double sense, for he had not made his toilet; it was in the days of the threatened water-famine, and the boys had been warned not to waste water in washing, an injunction they cheerfully obeyed. I was anxious not to have the boy disturbed, so the spelling-class went right on while I set up the camera. It was an original class, original in its answers as in its looks. This was what I heard while I focused on poor Eddie:

The teacher: “Cheat! spell cheat.”

Boy spells correctly. Teacher: “Right! What is it to cheat?”

Boy: “To skin one, like Tommy–”

The teacher cut the explanation short, and ordering up another boy, bade him spell “nerve.” He did it. “What is nerve?” demanded the teacher; “what does it mean?”

NIGHT-SCHOOL IN THE WEST SIDE LODGING-HOUSE. EDWARD, THE LITTLE PEDLAR, CAUGHT NAPPING.

“Cheek! don’t you know,” said the boy, and at that moment I caught Buffalo blacking my sleeping pedlar’s face with ink, just in time to prevent his waking him up. Then it was that I heard the disturber’s story. He was a character, and no mistake. He had run away from Buffalo, whence his name, “beating” his way down on the trains, until he reached New York. He “shined” around until he got so desperately hard up that he had to sell his kit. Just about then he was discovered by an artist, who paid him to sit for him in his awful rags with his tousled hair that had not known the restraint of a cap for months. “Oh! it was a daisy job,” sighed Buffalo, at the recollection. He had only to sit still and crack jokes. Alas! Buffalo’s first effort at righteousness upset him. He had been taught in the lodging-house that to be clean was the first requisite of a gentleman, and on his first pay-day he went bravely, eschewing “craps,” and bought himself a new coat and had his hair cut. When, beaming with pride, he presented himself at the studio in his new character, the artist turned him out as no longer of any use to him. I am afraid that Buffalo’s ambition to be “like folks,” received a shock by this mysterious misfortune, that spoiled his career. A few days after that he was caught by a policeman in the street, at his old game of “craps.” The officer took him to the police court and arraigned him as a hardened offender. To the judge’s question if he had any home, he said frankly yes! in Buffalo, but he had run away from it.

“Now, if I let you go, will you go right back?” asked the magistrate, looking over the desk at the youthful prisoner. Buffalo took off his tattered cap and stood up on the foot-rail so that he could reach across the desk with his hand.

“Put it there, jedge!” he said. “I’ll go. Square and honest, I will.”

And he went. I never heard of him again.

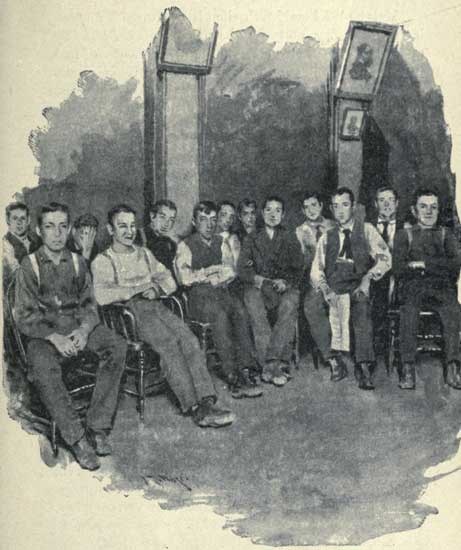

The evening classes are a sort of latch-key to knowledge for belated travellers on the road. They make good use of it, if they are late, as instanced in the class in history in the Duane Street lodging-house, which the younger boys irreverently speak of as “The Soup-house Gang.” I found it surprisingly proficient, if it was in its shirtsleeves, and there were at least a couple of pupils in it who promised to make their mark. All of its members are working lads, and not a few of them are capitalists in a small but very promising way. There is a savings bank attached to each lodging-house, with the superintendent as president and cashier at once. No less than $5,197 was deposited by the 11,435 boys who found shelter in them in 1891. They were not all depositors, of course. In the Duane Street lodging-house, out of 7,614 newsboys who were registered, 1,108 developed the instinct of saving, or were able to lay by something. Their little pile at the end of the year held the respectable sum of $3,162.39.26 It is safe to say that the interest of the Soup-house Gang in it was proportionate to its other achievements. In the West Side lodging-house, where nearly a thousand boys were taken in during the year, 54 patronized the bank and saved up $360.11. I found a little newsboy there who sells papers in the Grand Central Depot, and whose bank-book showed deposits of $200. Some day that boy, for all he has a “tough” father and mother who made him prefer the lodging-house as a home at the age of nine years, will be running the news business on the road as the capable “boss” of any number of lads of his present age. He neglects no opportunity to learn what the house has to offer, if he can get to the school in time. On the whole, the teachers report the boys as slow at their books, and no wonder. A glimpse of little Eddie, in from the cart after his day’s work and dropping asleep on the bench from sheer weariness, more than excuses him, I think. Eddie may have a chance now to learn something better than peddling apples. They have lately added to the nightly instruction there, I am told, the feature of manual training in the shape of a printing-office, to which the boys have taken amazingly and which promises great things.

There was one pupil in that evening class, at whose door the charge of being “slow” could not be laid, indifferent though his scholarship was in anything but the tricks of the street. He was the most hopeless young scamp I ever knew, and withal so aggravatingly funny that it was impossible not to laugh, no matter how much one felt like scolding. He lived by “shinin’” and kept his kit in a saloon to save his dragging it home every night. When I last saw him he was in disgrace, for not showing up at the school four successive nights. He explained that the policeman who “collared” him “fur fightin’” was to blame. It was the third time he had been locked up for that offence. When he found out that I wanted to know his history, he set about helping me with a readiness to oblige that was very promising. Did he have any home? Oh, yes, he had.

“Well, where do you live?” I asked.

“Here!” said Tommy, promptly, with just a suspicion of a wink at the other boys who were gathered about watching the examination. He had no father; didn’t know where his mother was.

“Is she any relation to you!” put in one of the boys, gravely. Tommy disdained the question. It turned out that his mother had been after him repeatedly and that he was an incorrigible runaway. She had at last given him up for good. While his picture was being “took”—it will be found on page 100 of this book—one of the lads reported that she was at the door again, and Tommy broke and ran. He returned just when they closed the doors of the house for the night, with the report that “the old woman was a fake.”

THE “SOUP-HOUSE GANG,” CLASS IN HISTORY IN THE DUANE STREET NEWSBOYS’ LODGING-HOUSE.

The crippled boys’ brush shop is a feature of the lodging-house in East Forty-fourth Street. It is the bête noire of the Society, partly on account of the difficulty of making it go without too great an outlay, partly on account of the boys themselves. They are of all the city’s outcasts the most unfortunate and the hardest to manage. Their misfortune has soured their temper, and as a rule they are troublesome and headstrong. No wonder. There seems to be no room for a poor crippled lad in New York. There are plenty of institutions that are after the well and able-bodied, but for the cripples the only chance is to shrivel and die in the Randall’s Island Asylum. No one wants them. The brush shop pays them wages that enables them to make their way, and the boys turn out enough brushes, if a market could only be found for them. It is a curious and saddening fact that the competition that robs it of its market comes from the prisons, to block the doors of which the Society expends all its energies—the prisons of other States than our own at that. The managers have a good word to say for the trades unions, which have been very kind to them, they say, in this matter of brushes, trying to help the boys, but without much success. The shop is able to employ only a small fraction of the number it might benefit, were it able to dispose of its wares readily. Despite their misfortunes the cripples manage to pick up and enjoy the good things they find in their path as they hobble through life. Last year they challenged the other crippled boys in the hospital on Randall’s Island to a champion game of base-ball, and beat them on their crutches with a score of 42 to 31. The game was played on the hospital lawn, before an enthusiastic crowd of wrecks, young and old, and must have been a sight to see.