полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 2

3. Subcastes continued.

Certain subcastes are of an occupational nature, and among these may be mentioned the Budalgirs of Chhindwāra, who derive their name from the budla, or leather bag made for the transport and storage of oil and ghī. The budla, Mr. Trench remarks,449 has been ousted by the kerosene oil tin, and the industry of the Budalgirs has consequently almost disappeared; but the budlas are still used by barbers to hold oil for the torches which they carry in wedding processions. The Daijanya subcaste are so named because their women act as midwives (dai), but this business is by no means confined to one particular group, being undertaken generally by Chamār women. The Kataua or Katwa are leather-cutters, the name being derived from kātna, to cut. And the Gobardhua (from gobar, cowdung) collect the droppings of cattle on the threshing-floors and wash out and eat the undigested grain. The Mochis or shoemakers and Jīngars450 or saddlemakers and bookbinders have obtained a better position than the ordinary Chamārs, and have now practically become separate castes; while, on the other hand, the Dohar subcaste of Narsinghpur have sunk to the very lowest stage of casual labour, grass-cutting and the like, and are looked down on by the rest of the caste.451 The Korchamārs are said to be the descendants of alliances between Chamārs and Koris or weavers, and the Turkanyas probably have Turk or Musalmān blood in their veins. In Berār the Romya or Haralya subcaste claim the highest rank and say that their ancestor Harlya was the primeval Chamār who stripped off a piece of his own skin to make a pair of shoes for Mahādeo.452 The Māngya453 Chamārs of Chānda and the Nona Chamārs of Damoh are groups of beggars, who are the lowest of the caste and will take food from the hands of any other Chamār. The Nona group take their name from Nona or Lona Chamārin, a well-known witch about whom Mr. Crooke relates the following story:454 “Her legend tells how Dhanwantari, the physician of the gods, was bitten by Takshaka, the king of the snakes, and knowing that death approached he ordered his sons to cook and eat his body after his death, so that they might thereby inherit his skill in medicine. They accordingly cooked his body in a cauldron, and were about to eat it when Takshaka appeared to them in the form of a Brāhman and warned them against this act of cannibalism. So they let the cauldron float down the Ganges, and as it floated down, Lona the Chamārin, who was washing on the bank of the river, took the vessel out in ignorance of its contents, and partook of the ghastly food. She at once obtained power to cure diseases, and especially snake-bite. One day all the women were transplanting rice, and it was found that Lona could do as much work as all her companions put together. So they watched her, and when she thought she was alone she stripped off her clothes (nudity being an essential element in magic), muttered some spells, and threw the plants into the air, when they all settled down in their proper places. Finding she was observed, she tried to escape, and as she ran the earth opened, and all the water of the rice-fields followed her and thus was formed the channel of the Loni River in the Unao District.” This Lona or Nona has obtained the position of a nursery bogey, and throughout Hindustān, Sir H. Risley states, parents frighten naughty children by telling them that Nona Chamārin will carry them off. The Chamārs say that she was the mother or grandmother of the prophet Ravi Dās, or Rai Dās already referred to.

4. Exogamous divisions.

The caste is also divided into a large number of exogamous groups or sections, whose names, as might be expected, present a great diversity of character. Some are borrowed from Rājpūt clans, as Sūrajvansi, Gaharwār and Rāthor; while others, as Marai, are taken from the Gonds. Instances of sections named after other castes are Banjar (Banjāra), Jogi, Chhipia (Chhipi, a tailor) and Khairwār (a forest tribe). The Chhipia section preserve the memory of their comparatively illustrious descent by refusing to eat pork. Instances of sections called after a title or nickname of the reputed founder are Mālādhāri, one who wears a garland; Māchhi-Mundia or fly-headed, perhaps the equivalent of feather-brained; Hathīla, obstinate; Bāghmār, a tiger-killer; Māngaya, a beggar; Dhuliya, a drummer; Jadkodiha, one who digs for roots, and so on. There are numerous territorial groups named after the town or village where the ancestor of the clan may be supposed to have lived; and many names also are of a totemistic nature, being taken from plants, animals or natural objects. Among these are Khunti, a peg; Chandaniha, sandalwood; Tarwāria, a sword; Borbans, plums; Miri, chillies; Chauria, a whisk; Baraiya, a wasp; Khalaria, a hide or skin; Kosni, kosa or tasar silk; and Purain, the lotus plant. Totemistic observances survive only in one or two isolated instances.

5. Marriage.

A man must not take a wife from his own section, nor in some localities from that of his mother or either of his grandmothers. Generally the union of first cousins is prohibited. Adult marriage is the rule, but those who wish to improve their social position have taken to disposing of their daughters at an early age. Matches are always arranged by the parents, and it is the business of the boy’s father to find a bride for his son. A bride-price is paid which may vary from two pice (farthings) to a hundred rupees, but usually averages about twenty rupees. In Chānda the amount is fixed at Rs. 13 and it is known as hunda, but if the bride’s grandmother is alive it is increased to Rs. 15–8, and the extra money is given to her. The marriage ceremony follows the standard type prevalent in the locality. On his journey to the girl’s house the boy rides on a bullock and is wrapped up in a blanket. In Bilāspur a kind of sham fight takes place between the parties, which is a reminiscence of the former practice of marriage by capture and is thus described as an eye-witness by the Rev. E. M. Gordon of Mungeli:455

“As the bridegroom’s party approached the home of the bride the boy’s friends lifted him up on their shoulders, and, surrounding him on every side, they made their way to the bride’s house, swinging round their sticks in a threatening manner. On coming near the house they crossed sticks with the bride’s friends, who gradually fell back and allowed the bridegroom’s friends to advance in their direction. The women of the house gathered with baskets and fans and some threw about rice in pretence of self-defence. When the sticks of the bridegroom’s party struck the roof of the bride’s house or of the marriage-shed her friends considered themselves defeated and the sham fight was at an end.” Among the Marātha Chamārs of Betūl two earthen pots full of water are half buried in the ground and worship is paid to them. The bride and bridegroom then stand together and their relatives take out water from the pots and pour it on to their heads from above. The idea is that the pouring of the sacred water on to them will make them grow, and if the bride is much smaller than the bridegroom more water is poured on to her in order that she may grow faster. The practice may symbolise the fertilising influence of rain. Among the Dohar Chamārs of Narsinghpur the bride and bridegroom are seated on a plough-yoke while the marriage ceremony is performed. Before the wedding the bride’s party take a goat’s leg in a basket with other articles to the janwāsa or bridegroom’s lodging and present it to his father. The bride and bridegroom take the goat’s leg and beat each other with it alternately. Another ceremony, known as Pendpūja, consists in placing pieces of stick with cotton stuck to the ends in an oven and burning them in the name of the deceased ancestors; but the significance, if there be any, of this rite is obscure. Some time after the wedding the bride is taken to her husband’s house to live with him, and on this occasion a simple ceremony known as Chauk or Pathoni is performed.

6. Widow-marriage and divorce.

Widows commonly remarry, and may take for their second husband anybody they please, except their own relatives and their late husband’s elder brother and ascendant relations. In Chhattīsgarh widows are known either as barandi or randi, the randi being a widow in the ordinary sense of the term and the barandi a girl who has been married but has not lived with her husband. Such a girl is not required to break her bangles on her husband’s death, and, being more in demand as a second wife, her father naturally obtains a good price for her. To marry a woman whose husband is alive is known as chhandwe banāna, the term chhandwe implying that the woman has discarded, or has been discarded by, her husband. The second husband must in this case repay to the first husband the expenses incurred by him on his wedding. The marriage ceremony for a widow is of the simplest character, and consists generally of the presentation to her by her new husband of those articles which a married woman may use, but which should be forsworn by a widow, as representing the useless vanities of the world. Thus in Saugor the bridegroom presents his bride with new clothes, vermilion for the parting of her hair, a spangle for her forehead, lac dye for her feet, antimony for the eyes, a comb, glass bangles and betel-leaves. In Mandla and Seoni the bridegroom gives a ring, according to the English custom, instead of bangles. When a widow marries a second time her first husband’s property remains with his family and also the children, unless they are very young, when the mother may keep them for a few years and subsequently send them back to their father’s relatives. Divorce is permitted for a variety of causes, and is usually effected in the presence of the caste panchāyat or committee by the husband and wife breaking a straw as a symbol of the rupture of the union. In Chānda an image of the divorced wife is made of grass and burnt to indicate that to her husband she is as good as dead; if she has children their heads and faces are shaved in token of mourning, and in the absence of children the husband’s younger brother has this rite performed; while the husband gives a funeral feast known as Marti Jīti kā Bhāt, or ‘The feast of the living dead woman.’ In Chhattīsgarh marriage ties are of the loosest description, and adultery is scarcely recognised as an offence. A woman may go and live openly with other men and her husband will take her back afterwards. Sometimes, when two men are in the relation of Mahāprasād or nearest friend to each other, that is, when they have vowed friendship on rice from the temple of Jagannāth, they will each place his wife at the other’s disposal. The Chamārs justify this carelessness of the fidelity of their wives by the saying, ‘If my cow wanders and comes home again, shall I not let her into her stall?’ In Seoni, if a Chamār woman is detected in a misdemeanour with a man of the caste, both parties are taken to the bank of a tank or river, where their heads are shaved in the presence of the caste panchāyat or committee. They are then made to bathe, and the shoes of all the assembled Chamārs made up into two bundles and placed on their heads, while they are required to promise that they will not repeat the offence.

7. Funeral customs.

The caste usually bury the dead with the feet to the north, like the Gonds and other aboriginal tribes. They say that heaven is situated towards the north, and the dead man should be placed in a position to start for that direction. Another explanation is that the head of the earth lies towards the north, and yet another that in the Satyug or beginning of time the sun rose in the north; and in each succeeding Yug or era it has veered round the compass until now in the Kali Yug or Iron Age it rises in the east. In Chhattīsgarh, before burying a corpse, they often make a mark on the body with butter, oil or soot; and when a child is subsequently born into the same family they look for any kind of mark on the corresponding place on its body. If any such be found they consider the child as a reincarnation of the deceased person. Still-born children, and those who die before the Chathi or sixth-day ceremony of purification, are not taken to the burial-ground, but their bodies are placed in an earthen pot and interred below the doorway or in the courtyard of the house. In such cases no funeral feast is demanded from the family, and some people believe that the custom tends in favour of the mother bearing another child; others say, however, that its object is to prevent the tonhi or witch from getting hold of the body of the child and rousing its spirit to life to do her bidding as Matia Deo.456 In Seoni a curious rule obtains to the effect that the bodies of those who eat carrion or the flesh of animals dying a natural death should be cremated. In the northern Districts a bier painted white is used for a man and a red one for a woman.

8. Childbirth.

Among the better-class Chamārs it is customary to place a newborn child in a winnowing-fan on a bed of rice. The nurse receives the rice and she also goes round to the houses of the headman of the village and the relatives of the family and makes a mark with cowdung on their doors as an announcement of the birth, for which she receives a small present. In Chhattīsgarh a woman is given nothing to eat or drink on the day that a child is born and for two days afterwards. On the fourth day she receives a liquid decoction of ginger, the roots of the orai or khaskhas grass, areca-nut, coriander and turmeric and other hot substances, and in some places a cake of linseed or sesamum. She sometimes goes on drinking this mixture for as long as a month, and usually receives solid food for the first time on the sixth day after the birth, when she bathes and her impurity is removed. The child is not permitted to suckle its mother until the third day after it is born, but before this it receives a small quantity of a mixture made by boiling the urine of a calf with some medicinal root. In Chhattīsgarh it is a common practice to brand a child on the stomach on the name-day or sixth day after its birth; twenty or more small burns may be made with the point of a hansia or sickle on the stomach, and it is supposed that this operation will prevent it from catching cold. Another preventive for convulsions and diseases of the lungs is the rubbing of the limbs and body with castor-oil; the nurse wets her hands with the oil and then warms them before a fire and rubs the child. It is also held in the smoke of burning ajwāin plants (Carum copticum). Infants are named on the Chathi or sixth day, or sometimes on the twelfth day after birth. The child’s head is shaved, and the hair, known as Jhālar, thrown away, the mother and child are washed and the males of the family are shaved. The mother is given her first regular meal of grain and pulse cooked with pumpkins. A pregnant woman who is afraid that her child will die will sometimes sell it to a neighbour before its birth for five or six cowries.457 The baby will then be named Pachkouri or Chhekouri, and it is thought that the gods, who are jealous of the lives of children, will overlook one whose name shows it to be valueless. Children are often nicknamed after some peculiarity as Kānwa (one-eyed), Behra (deaf), Konda (dumb), Khurwa (lame), Kāri (black), Bhūri (fair). It does not follow that a child called Konda is actually dumb, but it may simply have been late in learning to speak. Parents are jealous of exposing their children to the gaze of strangers and especially of a crowd, in which there will almost certainly be some malignant person to cast the evil eye upon them. Young children are therefore not infrequently secluded in the house and deprived of light and air to an extent which is highly injurious to them.

9. Religion.

The caste worship the ordinary Hindu and village deities of the localities in which they reside, and observe the principal festivals. In Saugor the Chamārs have a family god, known as Marri, who is represented by a lump of clay kept in the cooking-room of the house. He is supposed to represent the ancestors of the family. The Seoni Chamārs especially worship the castor-oil plant. Generally the caste revere the rāmpi or skinning-knife with offerings of flour-cakes and cocoanuts on festival days. In Chhattīsgarh more than half the Chamārs belong to the reformed Satnāmi sect, by which the worship of images is at least nominally abolished. This is separately treated. Mr. Gordon states458 that it is impossible to form a clear conception of the beliefs of the village Chamārs as to the hereafter: “That they have the idea of hell as a place of punishment may be gathered from the belief that if salt is spilt the one who does this will in Patāl—or the infernal region—have to gather up each grain of salt with his eyelids. Salt is for this reason handed round with great care, and it is considered unlucky to receive it in the palm of the hand; it is therefore invariably taken in a cloth or in a vessel. There is a belief that the spirit of the deceased hovers round familiar scenes and places, and on this account, whenever it is possible, it is customary to destroy or desert the house in which any one has died. If a house is deserted the custom is to sweep and plaster the place, and then, after lighting a lamp, to leave it in the house and withdraw altogether. After the spirit of the dead has wandered around restlessly for a certain time it is said that it will again become incarnate and take the form of man or of one of the lower animals.”

10. Occupation.

The curing and tanning of hides is the primary occupation of the Chamār, but in 1911 only 80,000 persons, or about a seventh of the actual workers of the caste, were engaged in it, and by Satnāmis the trade has been entirely eschewed. The majority of the Chhattīsgarhi Chamārs are cultivators with tenant right, and a number of them have obtained villages. In the northern Districts, however, the caste are as a rule miserably poor, and none of them own villages. A very few are tenants, and the vast majority despised and bullied helots. The condition of the leather-working Chamārs is described by Mr. Trench as lamentable.459 Chief among the causes of their ruin has been the recently established trade in raw hides. Formerly the bodies of all cattle dying within the precincts of the village necessarily became the property of the Chamārs, as the Hindu owners could not touch them without loss of caste. But since the rise of the cattle-slaughtering industry the cultivator has put his religious scruples in his pocket, and sells his old and worn-out animals to the butchers for a respectable sum. “For a mere walking skeleton of a cow or bullock from two to four rupees may be had for the asking, and so long as he does not actually see or stipulate for the slaughter of the sacred animal, the cultivator’s scruples remain dormant. No one laments this lapse from orthodoxy more sincerely than the outcaste Chamār. His situation may be compared with that of the Cornish pilchard-fishers, for whom the growing laxity on the part of continental Roman Catholic countries in the observance of Lent is already more than an omen of coming disaster.”460

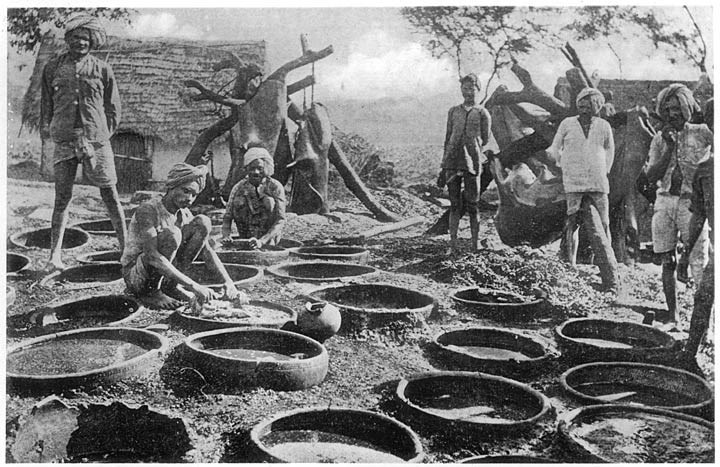

Chamārs tanning and working in leather.

11. The tanning process.

When a hide is to be cured the inside is first cleaned with the rāmpi, a chisel-like implement with a short blade four inches broad and a thick short handle. It is then soaked in a mixture of water and lime for ten or twelve days, and at intervals scraped clean of flesh and hair with the rāmpi. “The skill of a good tanner appears in the absence of superfluous inner skin, fat or flesh, remaining to be removed after the hide is finally taken out of the lime-pit. Next the hard berries of the ghont461 tree are poured into a large earthen vessel sunk in the ground, and water added till the mixture is so thick as to become barely liquid. In this the folded hide is dipped three or four times a day, undergoing meanwhile a vigorous rubbing and kneading. The average duration of this process is eight days, and it is followed by what is according to European ideas the real tanning. Using as thread the roots of the ubiquitous palās462 tree, the Chamār sews the hide up into a mussack-shaped bag open at the neck. The sewing is admirably executed, and when drawn tight the seams are nearly, but purposely not quite, water-tight. The hide is then hung on low stout scaffolding over a pit and filled with a decoction of the dried and semi-powdered leaves of the dhaura463 tree mixed with water. As the decoction trickles slowly through the seams below, more is poured on from above, and from time to time the position of the hide is reversed in such a way that the tanning permeates each part in turn. Sometimes only one reversal of the hide takes place half-way through the process, which occupies as a rule some eight days. But energetic Chamārs continually turn and refill the skin until satisfied that it is thoroughly saturated with the tanning. After a washing in clean water the hide is now considered to be tanned.”464

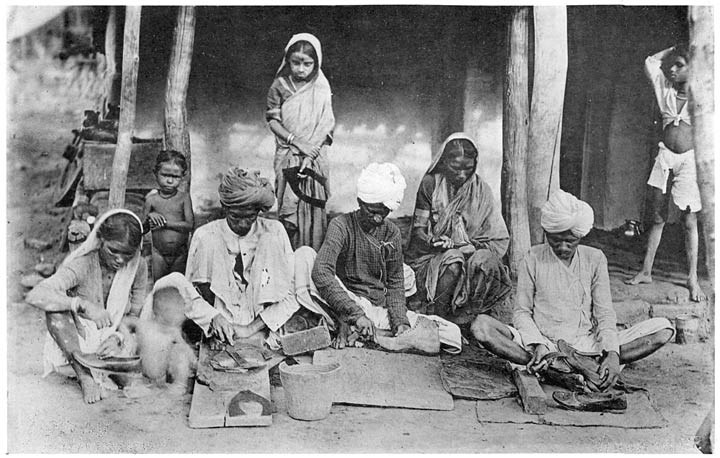

12. Shoes.

In return for receiving the hides of the village cattle the Chamār had to supply the village proprietor and his family with a pair of shoes each free of payment once a year, and sometimes also the village accountant and watchman; but the cultivators had usually to pay for them, though nowadays they also often insist on shoes in exchange for their hides. Shoes are usually worn in the wheat and cotton growing areas, but are less common in the rice country, where they would continually stick in the mud of the fields. The Saugor or Bundelkhandi shoe is a striking specimen of footgear. The sole is formed of as many as three layers of stout hide, and may be nearly an inch thick. The uppers in a typical shoe are of black soft leather, inlaid with a simple pattern in silver thread. These are covered by flaps of stamped yellow goat-skin cut in triangular and half-moon patterns, the interstices between the flaps being filled with red cloth. The heel-piece is continued more than half-way up the calf behind. The toe is pointed, curled tightly over backwards and surmounted by a brass knob. The high frontal shield protects the instep from mud and spear-grass, and the heel-piece ensures the retention of the shoe in the deepest quagmire. Such shoes cost one or two rupees a pair.465 In the rice Districts sandals are often worn on the road, and laid aside when the cultivator enters his fields. Women go bare-footed as a rule, but sometimes have sandals. Up till recently only prostitutes wore shoes in public, and no respectable woman would dare to do so. In towns boots and shoes made in the English fashion at Cawnpore and other centres have now been generally adopted, and with these socks are worn. The Mochis and Jīngars, who are offshoots from the Chamār caste, have adopted the distinctive occupations of making shoes and horse furniture with prepared leather, and no longer cure hides. They have thus developed into a separate caste, and consider themselves greatly superior to the Chamārs.

Chamārs cutting leather and making shoes.

13. Other articles made of leather.

Other articles made of leather are the thongs and nose-strings for bullocks, the buckets for irrigation wells, rude country saddlery, and mussacks and pakhāls for carrying water. These last are simply hides sewn into a bag and provided with an orifice. To make a pair of bellows a goat-skin is taken with all four legs attached, and wetted and filled with sand. It is then dried in the sun, the sand shaken out, the sticks fitted at the hind-quarters for blowing, and the pair of bellows is complete.

14. Customs connected with shoes.

The shoe, as everybody in India knows, is a symbol of the greatest degradation and impurity. This is partly on account of its manufacture from the impure leather or hide, and also perhaps because it is worn and trodden under foot. All the hides of tame animals are polluted and impure, but those of certain wild animals, such as the deer and tiger, are not so, being on the contrary to some extent sacred. This last feeling may be due to the fact that the old anchorites of the forests were accustomed to cover themselves with the skins of wild animals, and to use them for sitting and kneeling to pray. A Bairāgi or Vaishnava religious mendicant much likes to carry a tiger-skin on his body if he can afford one; and a Brāhman will have the skin of a black-buck spread in the room where he performs his devotions. Possibly the sin involved in killing tame animals has been partly responsible for the impurity attaching to their hides, to the obtaining of which the death of the animal must be a preliminary. Every Hindu removes his shoes before entering a house, though with the adoption of English boots a breach is being made in this custom. So far as the houses of Europeans are concerned, the retention of shoes is not, as might be imagined, of recent origin, but was noticed by Buchanan a hundred years ago: “Men of rank and their attendants continue to wear their shoes loose for the purpose of throwing them off whenever they enter a room, which they still continue to do everywhere except in the houses of Europeans, in which all natives of rank now imitate our example.” In this connection it must be remembered that a Hindu house is always sacred as the shrine of the household god, and shoes are removed before stepping across the threshold on to the hallowed ground. This consideration does not apply to European houses, and affords ground for dispensing with the removal of laced shoes and boots.