полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 2

The Marātha Brāhmans are also divided into sects, according to the Veda which they follow. Most of them are either Rigvedis or Yajurvedis, and these two sects marry among themselves. These Brāhmans are strict in the observance of caste rules. They do not take water from any but other Brāhmans, and abstain from flesh and liquor. They will, however, eat with any of the Pānch-Drāvid or southern divisions of Brāhmans except those of Gujarāt. They usually abstain from smoking, and until recently have made widows shave their heads; but this rule is perhaps now relaxed. As a rule they are well educated, and the majority of them look to Government service for a career, either as clerks in the public offices or as officers of the executive and judicial services. They are intelligent and generally reliable workers. The full name of a Marātha or Gujarāti Brāhman consists of his own name, his father’s name and a surname. But he is commonly addressed by his own name, followed by the honorific termination Rao for Rāja, a king, or Pant for Pandit, a wise man.

Brāhman, Maithil

Brāhman, Maithil.—One of the five Pānch-Gaur or northern divisions, comprising the Brāhmans of Bihār or Tirhūt. There are some Maithil Brāhman families settled in Mandla, who were formerly in the service of the Gond kings. They have the surname of Ojha, which is one of those borne by the caste and signifies a soothsayer. The Maithil Brāhmans are said to have at one time practised magic. Mithila or Bihār has also, from the earliest times, been famous for the cultivation of Sanskrit, and the great lawgiver Yajnavalkya is described as a native of this country.429 The head of the subcaste is the Mahārāja of Darbhanga, to whom family disputes are sometimes referred for decision. The Maithil Brāhmans are said to be mainly Sakti worshippers. They eat flesh and fish, but do not drink liquor or smoke tobacco.430

Brāhman, Mālwi

Brāhman, Mālwi.—This is a local class of Brāhmans from Mālwa in Central India, who are found in the Hoshangābād and Betūl Districts. They are said to have been invited here by the Gond kings of Kherla in Betūl six or more centuries ago, and are probably of impure descent. Mālwa is north of the Nerbudda, and they should therefore properly belong to the Pānch-Gaur division, but they speak Marāthi and their customs resemble those of Marātha Brāhmans, who will take food cooked without water from them. The Mālwi Brāhmans usually belong to the Madhyandina branch of the Yajurvedi sect. They work as village accountants (patwāris) and village priests, and also cultivate land.

Brāhman, Nāgar

Brāhman, Nāgar.—A class of Gujarāti Brāhmans found in the Nimār District. The name is said to be derived from the town of Vadnagar of Gujarāt, now in Baroda State. According to one account they accepted grants of land from a Rājpūt king, and hence were put out of caste by their fellows. Another story is that the Nāgar Brāhman women were renowned for their personal beauty and also for their skill in music. The emperor Jahāngir, hearing of their fame, wished to see them and sent for them, but they refused to go. The emperor then ordered that all the men should be killed and the women be taken to his Court. A terrible struggle ensued, and many women threw themselves into tanks and rivers and were drowned, rather than lose their modesty by appearing before the emperor. A body of Brāhmans numbering 7450 (or 74½ hundred) threw away their sacred threads and became Sūdras in order to save their lives. Since this occurrence the figure 74½ is considered very unlucky. Banias write 74½ in the beginning of their account-books, by which they are held to take a vow that if they make a false entry in the book they will be guilty of the sin of having killed this number of Brāhmans. The same figure is also written on letters, so that none but the person to whom they are addressed may dare to open them.431

The above stories seem to show that the Nāgar Brāhmans are partly of impure descent. In Gujarāt it is said that one section of them called Bārud are the descendants of Nāgar Brāhman fathers who were unable to get wives in their own caste and took them from others. The Bārud section also formerly permitted the remarriage of widows.432 This seems a further indication of mixed descent. The Nāgars settled in the Central Provinces have for a long time ceased to marry with those of Gujarāt owing to difficulties in communication. But now that the railway has been opened they have petitioned the Rao of Bhaunagar, who is the head of the caste, and a Nāgar Brāhman, to introduce intermarriage again between the two sections of the caste. Many Nāgar Brāhmans have taken to secular occupations and are land-agents and cultivators.

Formerly the Nāgar Brāhmans observed very strict rules about defilement when in the state called Nuven, that is, having bathed and purified themselves prior to taking food. A Brāhman in this condition was defiled if he touched an earthen vessel unless it was quite new and had never held water. If he sat down on a piece of cotton cloth or a scrap of leather or paper he became impure unless Hindu letters had been written on the paper; these, as being the goddess Sāraswati, would preserve it from defilement. But cloth or leather could not be purified through being written on. Thus if the Brāhman wished to read any book before or at his meal it had to be bound with silk and not with cotton; leather could not be used, and instead of paste of flour and water the binder had to employ paste of pounded tamarind seed. A printed book could not be read, because printing-ink contained impure matter. Raw cotton did not render the Brāhman impure, but if it had been twisted into the wick of a lamp by any one not in a state of purity he became impure. Bones defiled, but women’s ivory armlets did not, except in those parts of the country where they were not usually worn, and then they did. The touch of a child of the same caste who had not learned to eat grain did not defile, but if the child ate grain it did. The touch of a donkey, a dog or a pig defiled; some said that the touch of a cat also defiled, but others were inclined to think it did not, because in truth it was not easy to keep the cat out.433

If a Brāhman was defiled and rendered impure by any of the above means he could not proceed with his meal.

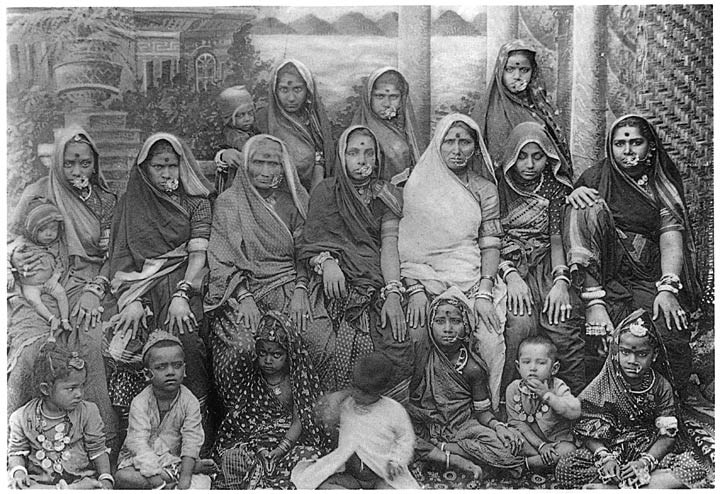

Group of Nāramdeo Brāhman women.

Brāhman, Nāramdeo

Brāhman, Nāramdeo.—A class of Brāhmans who live in the Hoshangābād and Nimār Districts near the banks of the Nerbudda, from which river their name is derived. According to their own account they belong to the Gurjara or Gujarāti division, and were expelled from Gujarāt by a Rāja who had cut up a golden cow and wished them to accept pieces of it as presents. This they refused to do on account of the sin involved, and hence were exiled and came to the Central Provinces. A local legend about them is to the effect that they are the descendants of a famous Rishi or saint, who dwelt beside the Nerbudda, and of a Naoda or Dhīmar woman who was one of his disciples. The Nāramdeo Brāhmans have for the most part adopted secular occupations, though they act as village priests or astrologers. They are largely employed as village accountants (patwāris), clerks in Government offices, and agents to landowners, that is, in very much the same capacity as the Kāyasths. As land-agents they show much astuteness, and are reputed to have enriched themselves in many cases at the expense of their masters. Hence they are unpopular with the cultivators just as the Kāyasths are, and very uncomplimentary proverbs are current about them.

Brāhman, Sanādhya

Brāhman, Sanādhya, Sanaurhia.—The Sanādhyas are considered in the Central Provinces to be a branch of the Kanaujia division. Their home is in the Ganges-Jumna Doāb and Rohilkhand, between the Gaur Brāhmans to the north-west and the Kanaujias to the east. Mr. Crooke states that in some localities the Sanādhyas intermarry with both the Kanaujia and Gaur divisions. But formerly both Kanaujias and Gaurs practised hypergamy with the Sanādhyas, taking daughters from them in marriage but not giving their daughters to them.434 This fact indicates the inferiority of the Sanādhya group, but marriage is now becoming reciprocal. In Bengal the Sanādhyas account for their inferiority to the other Kanaujias by saying that their ancestors on one occasion at the bidding of a Rāja partook of a sacrificial feast with all their clothes on, instead of only their loin-cloths according to the rule among Brāhmans, and were hence degraded. The Sanādhyas themselves have two divisions, the Sārhe-tīn ghar and Dasghar, or Three-and-a-half houses and Ten houses, of whom the former are superior, and practise hypergamy with the latter. Further, it is said that the Three-and-a-half group were once made to intermarry with the degraded Kataha or Mahā-Brāhmans, who are funeral priests.435 This further indicates the inferior status of the Sanādhyas. The Sanaurhia criminal caste of pickpockets are supposed to be made up of a nucleus of Sanādhya Brāhmans with recruits from all other castes, but this is not certain. In the Central Provinces a number of Sanādhyas took to carrying grain and merchandise on pack-bullocks, and are hence known as Belwār. They form a separate subcaste, ranking below the other Sanādhyas and marrying among themselves. Mr. Crooke notes that at their weddings the Sanādhyas worship a potter’s wheel. Some make an image of it on the wall of the house, while others go to the potter’s house and worship his wheel there. In the Central Provinces after the wedding they get a bed newly made with newār tape and seat the bride and bridegroom on it, and put a large plate at their feet, in which presents are placed. The Sanādhyas differ from the Kanaujias in that they smoke tobacco but do not eat meat, while the Kanaujias eat meat but do not smoke. They greet each other with the word Dandāwat, adding Mahārāj to an equal or superior.

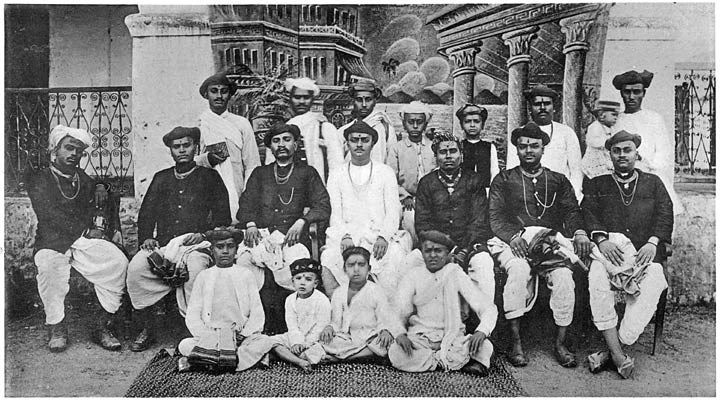

Group of Nāramdeo Brāhman men.

Brāhman, Sarwaria

Brāhman, Sarwaria.—This is the highest class of the Kanaujia Brāmans, who take their name from the river Sarju or Gogra in Oudh, where they have their home. They observe strict rules of ceremonial purity, and do not smoke tobacco nor plough with their own hands. An orthodox Sarwaria Brāman will not give his daughter in marriage in a village from which his family has received a girl, and sometimes will not even drink the water of that village. The Sarwarias make widows dress in white and sometimes shave their heads. In some tracts they intermarry with the Kanaujia Brāhmans, and in others take daughters in marriage but do not give their own daughters to them. In Dr. Buchanan’s time, a century ago, the Sarwaria Brāhmans would not eat rice sold in the bazār which had been cleaned in boiling water, as they considered that it had thereby become food cooked with water; and they carried their own grain to the grain-parcher to be prepared for them. When they ate either parched grain or sweetmeats from a confectioner in public they must purify the place on which they sat down with cowdung and water.436 This may be compared with a practice observed by very strict Brāhmans even now, of adding water to the medicine which they obtain from a Government dispensary, to purify it before drinking it.

Brāhman, Utkal

Brāhman, Utkal.—These are the Brāhmans of Orissa and one of the Pānch-Gaur divisions. They are divided into two groups, the Dākshinatya or southern and the Jajpuria or northern clan. The Utkal Brāhmans, who first settled in Sambalpur, are known as Jharia or jungly, and form a separate subcaste, marrying among themselves, as the later immigrants refuse to intermarry with them. Another group of Orissa Brāhmans have taken to cultivation, and are known as Halia, from hal, a plough. They grow the betel-vine, and in Orissa the areca and cocoanuts, besides doing ordinary cultivation. They have entirely lost their sacerdotal character, but glory in their occupation, and affect to despise the Bed or Veda Brāhmans, who live upon alms.437 A third class of Orissa Brāhmans are the Pandas, who serve as priests and cooks in the public temples and also in private houses, and travel about India touting for pilgrims to visit the temple at Jagannāth. Dr. Bhattachārya describes the procedure of the temple-touts as follows:438

“Their tours are so organised that during their campaigning season, which commences in November and is finished by the car-festival at the beginning of the rains, very few villages of the adjoining Provinces escape their visits and taxation. Their appearance causes a disturbance in every household. Those who have already visited ‘The Lord of the World’ at Puri are called upon to pay an instalment towards the debt contracted by them while at the sacred shrine, which, though paid many times over, is never completely satisfied. That, however, is a small matter compared with the misery and distraction caused by the ‘Jagannāth mania,’ which is excited by the preachings and pictures of the Panda. A fresh batch of old ladies become determined to visit the shrine, and neither the waitings and protestations of the children nor the prospect of a long and toilsome journey can dissuade them. The arrangements of the family are for the time being altogether upset, and the grief of those left behind is heightened by the fact that they look upon the pilgrims as going to meet almost certain death....”

This vivid statement of the objections to the habit of pilgrimage from a Brāhman writer is very interesting. Since the opening of the railway to Puri the danger and expense as well as the period of absence have been greatly reduced; but the pilgrimages are still responsible for a large mortality, as cholera frequently breaks out among the vast assembly at the temple, and the pilgrims, hastily returning to all parts of India, carry the disease with them, and cause epidemics in many localities. All castes now eat the rice cooked at the temple of Jagannāth together without defilement, and friendships are cemented by eating a little of this rice together as a sacred bond.

Chadār

Chadār, 439 Kotwar.—A small caste of weavers and village watchmen resident in the Districts of Saugor, Damoh, Jubbulpore and Narsinghpur. They numbered 28,000 persons in 1911. The caste is not found outside the northern Districts of the Central Provinces. The name is derived from the Sanskrit chirkar, a weaver, and belongs to Bundelkhand, but beyond this the Chadārs have no knowledge or traditions of their origin. They are probably an occupational group formed from members of the Dravidian tribes and others who took to the profession of village watchmen. A number of other occupational castes of low status are found in the northern Districts, and their existence is probably to be accounted for by the fact that the forest tribes were subjected and their tribal organisation destroyed by the invading Bundelas and other Hindus some centuries ago. They were deprived of the land and relegated to the performance of menial and servile duties in the village, and they have formed a new set of divisions into castes arising from the occupations they adopted. The Chadārs have two subcastes based on differences of religious practice, the Parmesuria or worshippers of Vishnu, and Athia or devotees of Devi. It is doubtful, however, whether these are strictly endogamous. They have a large number of exogamous septs or bainks, which are named after all sorts of animals, plants and natural objects. Instances of these names are Dhāna (a leaf of the rice plant), Kāsia (bell-metal), Gohia (a kind of lizard), Bachhulia (a calf), Gujaria (a milkmaid), Moria (a peacock), Laraiya (a jackal), Khatkīra (a bug), Sugaria (a pig), Barraiya (a wasp), Neora (a mongoose), Bhartu Chiraiya (a sparrow), and so on. Thirty-nine names in all are reported. Members of each sept draw the figure of the animal or plant after which it is named on the wall at marriages and worship it. They usually refuse to kill the totem animal, and the members of the Sugaria or pig sept throw away their earthen vessels if a pig should be killed in their sight, and clean their houses as if on the death of a member of the family. Marriage between members of the same sept is forbidden and also between first cousins and other near relations. The Chadārs say that the marriages of persons nearly related by blood are unhappy, and occasion serious consequences to the parties and their families. Girls are usually wedded in the fifth, seventh, ninth, or eleventh year of their age and boys between the ages of eight and sixteen. If an unmarried girl is seduced by a member of the caste she is married to him by the simple form adopted for the wedding of a widow. But if she goes wrong with an outsider of low caste she is permanently expelled. The remarriage of widows is permitted and divorce is also allowed, a deed being executed on stamped paper before the panchāyat or caste committee. If a woman runs away from her husband to another man he must repay to the husband the amount expended on her wedding and give a feast to the caste. A Brāhman is employed to fix the date of a wedding and sometimes for the naming of children, but he is only consulted and is never present at the ceremony. The caste venerate the goddess Devi, offering her a virgin she-goat in the month of Asārh (June-July). They worship their weaving implements at the Diwāli and Holi festivals, and feed the crows in Kunwār (September-October) as representing the spirits of their ancestors. This custom is based on the superstition that a crow does not die of old age or disease, but only when it is killed. To cure a patient of fever they tie a blue thread, irregularly knotted, round his wrist. They believe that thunder-bolts are the arrows shot by Indra to kill his enemies in the lower world, and that the rainbow is Indra’s bow; any one pointing at it will feel pain in his finger. The dead are mourned for ten days, and during that time a burning lamp is placed on the ground at some distance from the house, while on the tenth day a tooth-stick and water and food are set out for the soul of the dead. They will not throw the first teeth of a child on to a tiled roof, because they believe that if this is done his next teeth will be wide and ugly like the tiles. But it is a common practice to throw the first teeth on to the thatched roof of the house. The Chadārs will admit members of most castes of good standing into the community, and they eat flesh, including pork and fowls, and drink liquor, and will take cooked food from most of the good castes and from Kalārs, Khangārs and Kumhārs. The social status of the caste is very low, but they rank above the impure castes and are of cleanly habits, bathing daily and cleaning their kitchens before taking food. They are employed as village watchmen and as farmservants and field-labourers, and also weave coarse country cloth.

Chamār

1. General notice of the caste.

Chamār, Chambhār. 440—The caste of tanners and menial labourers of northern India. In the Central Provinces the Chamārs numbered about 900,000 persons in 1911. They are the third caste in the Province in numerical strength, being exceeded by the Gonds and Kunbis. About 600,000 persons, or two-thirds of the total strength of the caste in the Province, belong to the Chhattīsgarh Division and adjacent Feudatory States. Here the Chamārs have to some extent emancipated themselves from their servile status and have become cultivators, and occasionally even mālguzārs or landed proprietors; and between them and the Hindus a bitter and long-standing feud is in progress. Outside Chhattīsgarh the Chamārs are found in most of the Hindi-speaking Districts whose population has been recruited from northern and central India, and here they are perhaps the most debased class of the community, consigned to the lowest of menial tasks, and their spirit broken by generations of servitude. In the Marātha country the place of the Chamārs is taken by the Mehras or Mahārs. In the whole of India the Chamārs are about eleven millions strong, and are the largest caste with the exception of the Brāhmans. The name is derived from the Sanskrit Charmakāra, a worker in leather; and, according to classical tradition, the Chamār is the offspring of a Chandāl or sweeper woman by a man of the fisher caste.441 The superior physical type of the Chamār has been noticed in several localities. Thus in the Kanara District of Bombay442 the Chamār women are said to be famed for their beauty of face and figure, and there it is stated that the Padminis or perfect type of women, middle-sized with fine features, black lustrous hair and eyes, full breasts and slim waists,443 are all Chamārins. Sir D. Ibbetson writes444 that their women are celebrated for beauty, and loss of caste is often attributed to too great a partiality for a Chamārin. In Chhattīsgarh the Chamārs are generally of fine stature and fair complexion; some of them are lighter in colour than the Chhattīsgarhi Brāhmans, and it is on record that a European officer mistook a Chamār for a Eurasian and addressed him in English. This, however, is by no means universally the case, and Sir H. Risley considers445 that “The average Chamār is hardly distinguishable in point of features, stature or complexion from the members of those non-Aryan races from whose ranks we should primarily expect the profession of leather-dressers to be recruited.” Again, Sir Henry Elliot, writing of the Chamārs of the North-Western Provinces, says: “Chamārs are reputed to be a dark race, and a fair Chamār is said to be as rare an object as a black Brāhman:

Karia Brāhman, gor Chamār,Inke sāth nā utariye pār,that is, ‘Do not cross a river in the same boat with a black Brāhman or a fair Chamār,’ both being of evil omen.” The latter description would certainly apply to the Chamārs of the Central Provinces outside the Chhattīsgarh Districts, but hardly to the caste as a whole within that area. No satisfactory explanation has been offered of this distinction of appearance of some groups of Chamārs. It is possible that the Chamārs of certain localities may be the descendants of a race from the north-west, conquered and enslaved by a later wave of immigrants; or that their physical development may owe something to adult marriage and a flesh diet, even though consisting largely of carrion. It may be noticed that the sweepers, who eat the broken food from the tables of the Europeans and wealthy natives, are sometimes stronger and better built than the average Hindu. Similarly, the Kasais or Muhammadan butchers are proverbially strong and lusty. But no evidence is forthcoming in support of such conjectures, and the problem is likely to remain insoluble.

“The Chamārs,” Sir H. Risley states,446 “trace their own pedigree to Ravi or Rai Dās, the famous disciple of Rāmānand at the end of the fourteenth century, and whenever a Chamār is asked what he is, he replies a Ravi Dās. Another tradition current among them alleges that their original ancestor was the youngest of four Brāhman brethren who went to bathe in a river and found a cow struggling in a quicksand. They sent the youngest brother in to rescue the animal, but before he could get to the spot it had been drowned. He was compelled, therefore, by his brothers to remove the carcase, and after he had done this they turned him out of their caste and gave him the name of Chamār.” Other legends are related by Mr. Crooke in his article on the caste.

2. Endogamous divisions.

The Chamārs are broken up into a number of endogamous subcastes. Of these the largest now consists of the members of the Satnāmi sect in Chhattīsgarh, who do not intermarry with other Chamārs. They are described in the article on that sect. The other Chamārs call the Satnāmis Jharia or ‘jungly’, which implies that they are the oldest residents in Chhattīsgarh. The Satnāmis are all cultivators, and have given up working in leather. The Chungias (from chungi, a leaf-pipe) are a branch of the Satnāmis who have taken to smoking, a practice which is forbidden by the rules of the sect. In Chhattīsgarh those Chamārs who still cure hides and work in leather belong either to the Kanaujia or Ahirwār subcastes, the former of whom take their name from the well-known classical town of Kanauj in northern India, while the latter are said to be the descendants of unions between Chamār fathers and Ahīr mothers. The Kanaujias are much addicted to drink, and though they eat pork they do not rear pigs. The Ahirwārs, or Erwārs as they are called outside Chhattīsgarh, occupy a somewhat higher position than the Kanaujias. They consider themselves to be the direct descendants of the prophet Raidās or Rohidās, who, they say, had seven wives of different castes; one of them was an Ahīr woman, and her offspring were the ancestors of the Ahirwār subcaste. Both the Kanaujias and Ahirwārs of Chhattīsgarh are generally known to outsiders as Paikaha, a term which indicates that they still follow their ancestral calling of curing hides, as opposed to the Satnāmis, who have generally eschewed it. Those Chamārs who are curriers have, as a rule, the right to receive the hides of the village cattle in return for removing the carcases, each family of Chamārs having allotted to them a certain number of tenants whose dead cattle they take, while their women are the hereditary midwives of the village. Such Chamārs have the designation of Meher. The Kanaujias make shoes out of a single piece of leather, while the Ahirwārs cut the front separately. The latter also ornament their shoes with fancy work consisting of patterns of silver thread on red cloth. No Ahirwār girl is married until she has shown herself proficient in this kind of needlework.447 Another well-known group, found both in Chhattīsgarh and elsewhere, are the Jaiswāras, who take their name from the old town of Jais in the United Provinces. Many of them serve as grooms, and are accustomed to state their caste as Jaiswāra, considering it a more respectable designation than Chamār. The Jaiswāras must carry burdens on their heads only and not on their shoulders, and they must not tie up a dog with a halter or neck-rope, this article being venerated by them as an implement of their calling. A breach of either of these rules entails temporary excommunication from caste and a fine for readmission. Among a number of territorial groups may be mentioned the Bundelkhandi or immigrants from Bundelkhand; the Bhadoria from the Bhadāwar State; the Antarvedi from Antarved or the Doāb, the country lying between the Ganges and Jumna; the Gangāpāri or those from the north of the Ganges; and the Pardeshi (foreigners) and Desha or Deswār (belonging to the country), both of which groups come from Hindustān. The Deswār Chamārs of Narsinghpur448 are now all agriculturists and have totally abjured the business of working in leather. The Mahobia and Khaijrāha take their names from the towns of Mahoba and Khaijra in Central India. The Lādse or Lādvi come from south Gujarāt, which in classical times was known as Lāt; while the Marātha, Berāria and Dakhini subdivisions belong to southern India. There are a number of other territorial groups of less importance.