полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 2

18. Social position.

The Brāhman is of course supreme in Hindu society. He never bows his head in salutation to any one who is not a Brāhman, and acknowledges with a benediction the greetings of all other classes. No member of another caste, Dr. Bhattachārya states, can, consistently with Hindu etiquette and religious beliefs, refuse altogether to bow to a Brāhman. “The more orthodox Sūdras carry their veneration for the priestly caste to such an extent that they will not cross the shadow of a Brāhman, and it is not unusual for them to be under a vow not to eat any food in the morning before drinking Brāhman nectar,418 or water in which the toe of a Brāhman has been dipped. On the other hand, the pride of the Brāhman is such that he does not bow even to the images of the gods in a Sūdra’s house. When a Brāhman invites a Sūdra the latter is usually asked to partake of the host’s prasāda or favour in the shape of the leavings of his plate. Orthodox Sūdras actually take offence if invited by the use of any other formula. No Sūdra is allowed to eat in the same room or at the same time with Brāhmans.”419

A man of low caste meeting a Brāhman says ‘Pailagi’ or ‘I fall at your feet,’ and touches the Brāhman’s foot with his hand, which he then carries to his own forehead to signify this. A man wishing to ask a favour in a humble manner stands on one leg and folds his cloth round his neck to show that his head is at his benefactor’s disposal; and he takes a piece of grass in his mouth by which he means to say, ‘I am your cow.’ Brāhmans greeting each other clasp the hands and say ‘Salaam,’ this method of greeting being known as Namaskar. Since most Brāhmans have abandoned the priestly calling and are engaged in Government service and the professions, this exaggerated display of reverence is tending to disappear, nor do the educated members of the caste set any great store by it, preferring the social estimation attaching to such a prominent secular position as they often attain for themselves.

19. Titles.

Any Brāhman is, however, commonly addressed by other castes as Mahārāj, great king, or else as Pandit, a learned man. I had a Brāhman chuprāssie, or orderly, who was regularly addressed by the rest of the household as Pandit, and on inquiring as to the literary attainments of this learned man, I found he had read the first two class-books in a primary school. Other titles of Brāhmans are Dvija, or twice-born, that is, one who has had the thread ceremony performed; Bipra, applied to a Brāhman learned in the Shāstras or scriptures; and Srotriya, a learned Brāhman who is engaged in the performance of Vedic rites.

20. Caste panchāyat and offences.

The Brāhmans have a caste panchāyat, but among the educated classes the tendency is to drop the panchāyat procedure and to refer matters of caste rules and etiquette to the informal decision of a few of the most respected local members. In northern India there is no supreme authority for the caste, but the five southern divisions acknowledge the successor of the great reformer Shankar Achārya as their spiritual head, and important caste questions are referred to him. His headquarters are at the monastery of Sringeri on the Cauvery river in Mysore. Mr. Joshi gives four offences as punishable with permanent exclusion from caste: killing a Brāhman, drinking prohibited wine or spirits, committing incest with a mother or step-mother or with the wife of one’s spiritual preceptor, and stealing gold from a priest. Some very important offences, therefore, such as murder of any person other than a Brāhman, adultery with a woman of impure caste and taking food from her, and all offences against property, except those mentioned, do not involve permanent expulsion. Temporary exclusion is inflicted for a variety of offences, among which are teaching the Vedas for hire, receiving gifts from a Sūdra for performing fire-worship, falsely accusing a spiritual preceptor, subsisting by the harlotry of a wife, and defiling a damsel. It is possible that some of the offences against morality are comparatively recent additions. Brāhmans who cross the sea to be educated in England are readmitted into caste on going through various rites of purification; the principal of these is to swallow the five products of the sacred cow, milk, ghī or preserved butter, curds, dung and urine. But the small minority who have introduced widow-marriage are still banned by the orthodox.

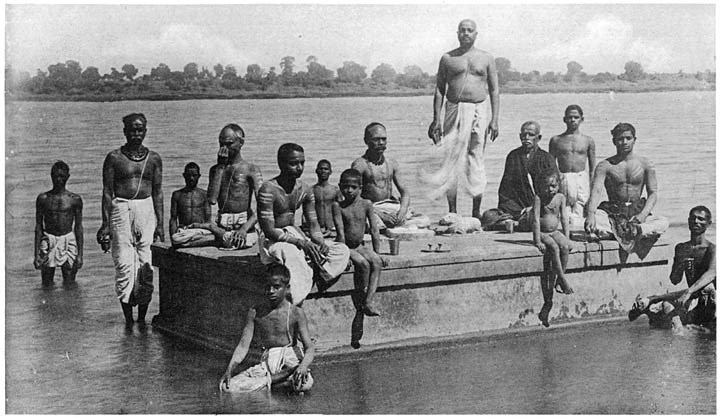

Brāhman bathing party.

21. Rules about food.

Brāhmans as a rule should not eat meat nor drink intoxicating liquor. But it is said that the following indulgences have been recognised: for residents in eastern India the eating of flesh and drinking liquor; for those of northern India the eating of flesh; for those in the west the use of water out of leather buckets; and in the south marriage with a first cousin on the mother’s side. Hindustāni Brāhmans eat meat, according to Mr. Joshi, and others are now also adopting this custom. The kinds of meat permitted are mutton and venison, scaly, but not scaleless, fish, hares, and even the tortoise, wild boar, wild buffalo and rhinoceros. Brāhmans are said even to eat domestic fowls, though not openly, and wild jungle fowls are preferred, but are seldom obtainable. Marātha Brāhmans will not eat meat openly. Formerly only the flesh of animals offered in sacrifice could be eaten, but this rule is being disregarded and some Brāhmans buy mutton from the butchers. A Brāhman should not eat even pakki rasoi or food cooked without water, such as sweetmeats and cakes fried in butter or oil, except when cooked by his own family and in his own home. But these are now partaken of abroad, and also purchased from the Halwai or confectioner on the assumption that he is a Brāhman. A Brāhman should take food cooked with water only from his own relations and in his own home after the place has been purified and spread with cowdung. He bathes before eating, and wears only a yellow silk or woollen cloth round his waist, which is kept specially for this purpose, cotton being regarded as impure. But these rules are tending to become obsolete, as educated Brāhmans recognise more and more what a hindrance they cause to any social enjoyment. Boys especially who receive an English education in high schools and universities are rapidly becoming more liberal. They will drink soda-water or lemonade of which they are very fond, and eat European sweets and sometimes biscuits. The social intercourse of boys of all castes and religions in school and games, and in the latter the frequent association with Europeans, are having a remarkable effect in breaking down caste prejudice, the results of which should become very apparent in a few years. A Brāhman also should not smoke, but many now do so, and when they go to see a friend will take their own huqqa with them as they cannot smoke out of his. Marātha and Khedawāl Brāhmans, however, as a rule do not smoke, but only chew tobacco.

22. Dress.

A Brāhman’s dress should be white, and he can have a coloured turban, preferably red. Marātha Brāhmans were very particular about the securing of their dhoti or loin-cloth, which always had to have five tucks, three into the waistband at the two sides and in front, while the loose ends were tucked in in front and behind. Buttons had to be avoided as they were made of bone, and shoes were considered to be impure as being of leather. Formerly a Brāhman never entered a house with his shoes on, as he would consider the house to be defiled. According to the old rule, if a Brāhman touches a man of an impure caste, as a Chamār (tanner) or Basor (basket-maker), he should bathe and change his loin-cloth, and if he touches a sweeper he should change his sacred thread. Now, however, educated Brāhmans usually wear white cotton trousers and black or brown coats of cloth, alpaca or silk with the normal allowance of buttons, and European shoes and boots which they keep on indoors. Boys are even discarding the choti or scalp-lock and simply cut their hair short in imitation of the English. For the head small felt caps have become fashionable in lieu of turbans.

23. Tattooing.

Men are never tattooed, but women are freely tattooed on the face and body. One dot is made in the centre of the forehead and three on the left nostril in the form of a triangle. All the limbs and the fingers and toes may also be tattooed, the most common patterns being a peacock with spread wings, a fish, cuckoo, scorpion, a child’s doll, a sieve, a pattern of Sīta’s cookroom and representations of all female ornaments. Some women think that they will be able to sell the ornaments tattooed on their bodies in the next world and subsist on the proceeds.

24. Occupation.

In former times the Brāhman was supposed to confine himself to priestly duties, learning the Vedas and giving instruction to the laity. His subsistence was to be obtained from gleaning the fields after the crop had been cut and from unsolicited alms, as it was disgraceful for him to beg. But if he could not make a living in this manner he was at liberty to adopt a trade or profession. The majority of Brāhmans have followed the latter course with much success. They were the ministers of Hindu kings, and as these were usually illiterate, most of the power fell into the Brāhmans’ hands. In Poona the Marātha Brāhmans became the actual rulers of the State. They have profited much from gifts and bequests of land for charitable purposes and are one of the largest landholding castes. In Mewār it was recorded that a fifth of the State revenue from land was assigned in religious grants,420 and in the deeds of gift, drawn up no doubt by the Brāhmans themselves, the most terrible penalties were invoked on any one who should interfere with the grant. One of these was that such an impious person would be a caterpillar in hell for sixty thousand years.421 Plots of land and mango groves are also frequently given to Brāhmans by village proprietors. A Brāhman is forbidden to touch the plough with his own hands, but this rule is falling into abeyance and many Brāhman cultivators plough themselves. Brāhmans are also prohibited from selling a large number of articles, as milk, butter, cows, salt and so on. Formerly a Brāhman village proprietor refused payment for the supplies of milk and butter given to travellers, and some would expend the whole produce of their cattle in feeding religious mendicants and poor Brāhmans. But these scruples, which tended to multiply the number of beggars indefinitely, have happily vanished, and Brāhmans will even sell cows to a butcher. Mr. Joshi relates that a suit was brought by a Brāhman in his court for the hide of a cow sold by him for slaughter. A number of Brāhmans are employed as personal servants, and these are usually cooks, a Brāhman cook being very useful, since all Hindus can eat the food which he prepares. Nor has this calling hitherto been considered derogatory, as food is held to be sacred, and he who prepares it is respected. Many live on charitable contributions, and it is a rule among Hindus that a Brāhman coming into the house and asking for a present must be given something or his curse will ruin the family. Liberality is encouraged by the recitation of legends, such as that of the good king Harischandra who gave away his whole kingdom to the great Brāhman saint Visvamitra, and retired to Benāres with a loin-cloth which the recipient allowed him to retain from his possessions. But Brāhmans who take gifts at the time of a death, and those who take them from pilgrims at the sacred shrines, are despised and considered as out of caste, though not the priests in charge of temples. The rapacity of all these classes is proverbial, and an instance may be given of the conduct of the Pandas or temple-priests of Benāres. These men were so haughty that they never appeared in the temple unless some very important visitor was expected, who would be able to pay largely. It is related that when the ex-Peshwa of Poona came to Benāres after the death of his father he solicited the Panda of the great temple of Viseshwar to assist him in the performance of the ceremonies necessary for the repose of his father’s soul. But the priest refused to do so until the Mahārāja had filled with coined silver the hauz or font of the temple. The demand was acceded to and Rs. 125,000 were required to fill the font.422 Those who are very poor adopt the profession of a Mahā-Brāhman or Mahāpātra, who takes gifts for the dead. Respectable Brāhmans will not accept gifts at all, but when asked to a feast the host usually gives them one to four annas or pence with betel-leaf at the time of their departure, and there is no shame in accepting this. A very rich man may give a gold mohar (guinea) to each Brāhman. Other Brāhmans act as astrologers and foretell events. They pretend to be able to produce rain in a drought or stop excessive rainfall when it is injuring the crops. They interpret dreams and omens. In the case of a theft the loser will go to a Brāhman astrologer, and after learning the circumstances the latter will tell him what sort of person stole the property and in what direction the property is concealed. But the large majority of Brāhmans have abandoned all priestly functions, and are employed in all grades of Government service, the professions and agriculture. In 1911 about fifty-three per cent of Brāhmans in the Central Provinces were supported by agriculture as landowners, cultivators and labourers. About twenty-two per cent were engaged in the arts and professions, seven per cent in Government service, including the police which contains many Brāhman constables, and only nineteen per cent were returned under all occupations connected with religion.

25. Character of Brāhmans.

Many hard things have been said about the Brāhman caste and have not been undeserved. The Brāhman priesthood displayed in a marked degree the vices of arrogance, greed, hypocrisy and dissimulation, which would naturally be engendered by their sacerdotal pretensions and the position they claimed at the head of Hindu society. But the priests and mendicants now, as has been seen, contribute only a comparatively small minority of the whole caste. The majority of the Brāhmans are lawyers, doctors, executive officers of Government and clerks in all kinds of Government, railway and private offices. The defects ascribed to the priesthood apply to these, if at all, only in a very minor degree. The Brāhman official has many virtues. He is, as a rule, honest, industrious and anxious to do his work creditably. He spends very little on his own pleasures, and his chief aim in life is to give his children as good an education as he can afford. A half or more of his income may be devoted to this object. If he is well-to-do he helps his poor relations liberally, having the strong fellow-feeling for them which is a relic of the joint family system. He is a faithful husband and an affectionate father. If his outlook on life is narrow and much of his leisure often devoted to petty quarrels and intrigues, this is largely the result of his imperfect, parrot-like education and lack of opportunity for anything better. In this respect it may be anticipated that the excellent education and training now afforded by Government in secondary schools for very small fees will produce a great improvement; and that the next generation of educated Hindus will be considerably more manly and intelligent, and it may be hoped at the same time not less honest, industrious and loyal than their fathers.

Brāhman, Ahivāsi

Brāhman, Ahivāsi.—A class of persons who claim to be Brāhmans, but are generally engaged in cultivation and pack-carriage. They are looked down upon by other Brāhmans, and permit the remarriage of widows. The name means the abode of the snake or dragon, and the caste are said to be derived from a village Sunrakh in Muttra District, where a dragon once lived. For further information Mr. Crooke’s article on the caste,423 from which the above details are taken, may be consulted.

Brāhman, Jijhotia

Brāhman, Jijhotia.—This is a local subdivision of the Kanaujia subcaste, belonging to Bundelkhand. They take their name from Jajhoti, the classical term for Bundelkhand, and reside in Saugor and the adjoining Districts, where they usually act as priests to the higher castes. The Jijhotia Brāhmans rank a little below the Kanaujias proper and the Sarwarias, who are also a branch of the Kanaujia division. The two latter classes take daughters in marriage from Jijhotias, but do not give their daughters to them. But these hypergamous marriages are now rare. Jijhotia Brāhmans will plough with their own hands in Saugor.

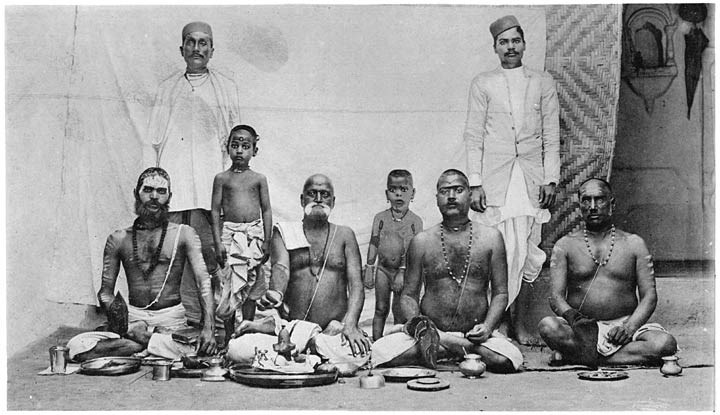

Brāhman Pujāris or priests.

Brāhman, Kanaujia, Kanyakubja

Brāhman, Kanaujia, Kanyakubja.—This, the most important division of the northern Brāhmans, takes its name from the ancient city of Kanauj in the Farukhābād District on the Ganges, which was on two occasions the capital of India. The great king Harsha Vardhana, who ruled the whole of northern India in the seventh century, had his headquarters here, and when the Chinese pilgrim Hiuen Tsang stayed at Kanauj in A.D. 638 and 643 he found upwards of a hundred monasteries crowded by more than 10,000 Buddhist monks. “Hinduism flourished as well as Buddhism, and could show more than two hundred temples with thousands of worshippers. The city, which was strongly fortified, extended along the east bank of the Ganges for about four miles, and was adorned with lovely gardens and clear tanks. The inhabitants were well-to-do, including some families of great wealth; they dressed in silk, and were skilled in learning and the arts.”424 When Mahmūd of Ghazni appeared before Kanauj in A.D. 1018 the number of temples is said to have risen to 10,000. The Sultan destroyed the temples, but seems to have spared the city. Thereafter Kanauj declined in importance, though still the capital of a Rājpūt dynasty, and the final sack by Shihāb-ud-Dīn in A.D. 1194 reduced it to desolation and insignificance for ever.425

The Kanaujia Brāhmans include the principal body of the caste in Bengal and in the Hindi Districts of the Central Provinces. They are here divided into four sub-groups, the Kanaujia proper, Sarwaria, Jijhotia and Sanādhya, which are separately noticed. The Sarwarias are sometimes considered to rank a little higher than the proper Kanaujias. It is said that the two classes are the descendants of two brothers, Kanya and Kubja, of whom the former accepted a present from the divine king Rāma of Ayodhya when he celebrated a sacrifice on his return from Ceylon, while the latter refused it. The Sarwarias are descended from Kubja who refused the present and therefore are purer than the Kanaujias, whose ancestor, Kanya, accepted it. Kanya and Kubja are simply the two parts of Kanyakubja, the old name for Kanauj. It may be noted that Kanya means a maiden and also the constellation Virgo, while Kubja is a name of the planet Mars; but it is not known whether the words in this sense are connected with the name of the city. The Kanaujia Brāhmans of the Central Provinces practise hypergamy, as described in the general article on Brāhman. Mr. Crooke states that in the United Provinces the children of a man’s second wife can intermarry with those of his first wife, provided that they are not otherwise related or of the same section. The practice of exchanging girls between families is also permitted there.426 In the Central Provinces the Kanaujias eat meat and sometimes plough with their own hands. The Chhattīsgarhi Kanaujias form a separate group, who have been long separated from their brethren elsewhere. As a consequence other Kanaujias will neither eat nor intermarry with them. Similarly in Saugor those who have come recently from the United Provinces will not marry with the older settlers. A Kanaujia Brāhman is very strict in the matter of taking food, and will scarcely eat it unless cooked by his own relations, according to the saying, ‘Ath Kanaujia, nau chulha’ or ‘Eight Kanaujias will want nine places to cook their food.’

Brāhman, Khedāwāl

Brāhman, Khedāwāl.—The Khedāwāls are a class of Gujarāti Brāhmans, who take their name from Kheda or Kaira, the headquarters of the Kaira District, where they principally reside. They have two divisions, known as Inside and Outside. It is said that once the Kaira chief was anxious to have a son and offered them gifts. The majority refused the gifts, and leaving Kaira settled in villages outside the town; while a small number accepted the gifts and remained inside, and hence two separate divisions arose, the outside group being the higher.427 It is said that the first Khedāwāl who came to the Central Provinces was on a journey from Gujarāt to Benāres when, on passing through Panna State, he saw some diamonds lying in a field. He stopped and picked up as many as he could and presented them to the Rāja of Panna, who made him a grant of an estate, and from this time other Khedāwāls came and settled. A considerable colony of them now exists in Saugor and Damoh. The Khedāwāls are clever and astute, and many of them are the agents of landowners and moneylenders, while a large proportion are in the service of the Government. They do not as a rule perform priestly functions in the Central Provinces. Their caste observances are strict. Formerly it is said that a Khedāwāl who was sent to jail was permanently expelled from caste, and though the rule has been relaxed the penalties for readmission are still very heavy. They do not smoke, but only chew tobacco. Widows must dress in white, and their heads are sometimes shaved. They are said to consider a camel as impure as a donkey, and will not touch either animal. One of their common titles is Mehta, meaning great. The Khedāwāls of the Central Provinces formerly married only among themselves, but since the railway has been opened intermarriage with their caste-fellows in Gujarāt has been resumed.

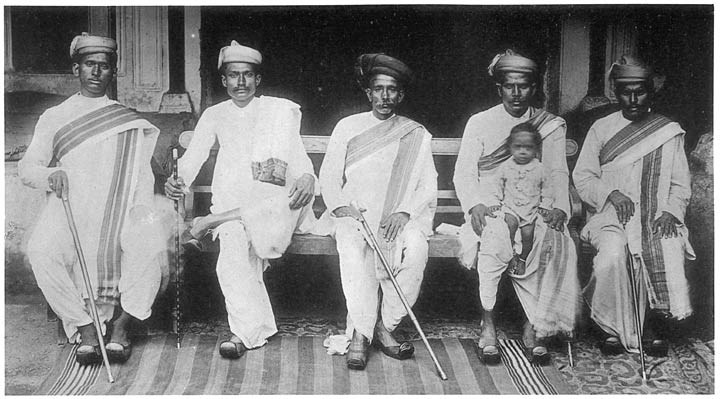

Group of Marātha Brāhman men.

Brāhman, Mahārāshtra

Brāhman, Mahārāshtra, Marātha.—The Marātha Brāhmans, or those of the Bombay country, are numerous and important in the Central Provinces. The northern Districts were for a period governed by Marātha Brāhmans on behalf of the Peshwa of Poona, and under the Bhonsla dynasty of Nāgpur in the south they took a large part in the administration. The Marātha Brāhmans have three main subcastes, the Deshasth, Konkonasth and Karhāda. The Deshasth Brāhmans belong to the country of Poona above the Western Ghats, which is known as the desh or home country. They are numerous in Berār and Nāgpur. The Konkonasth are so called because they reside in the Konkan country along the Bombay coast. They have noticeably fair complexions, good features and often grey eyes. According to a legend they were sprung from the corpses of a party of shipwrecked foreigners, who were raised to life by Parasurāma.428 This story and their fine appearance have given rise to the hypothesis that their ancestors were shipwrecked sailors from some European country, or from Arabia or Persia. They are also known as Chitpāvan, which is said to mean the pure in heart, but a derivation suggested in the Bombay Gazetteer is from Chiplun or Chitāpolan, a place in the Konkan which was their headquarters. The Peshwa of Poona was a Konkonasth Brāhman, and there are a number of them in Saugor. The Karhāda Brāhmans take their name from the town of Karhād in the Satāra District. They show little difference from the Deshasths in customs and appearance.

Formerly the above three subcastes were endogamous and married only among themselves. But since the railway has been opened they have begun to intermarry with each other to a limited extent, having obtained sanction to this from the successor of Shankar Achārya, whom they acknowledge as their spiritual head.

The Marātha Brāhmans are also divided into sects, according to the Veda which they follow. Most of them are either Rigvedis or Yajurvedis, and these two sects marry among themselves. These Brāhmans are strict in the observance of caste rules. They do not take water from any but other Brāhmans, and abstain from flesh and liquor. They will, however, eat with any of the Pānch-Drāvid or southern divisions of Brāhmans except those of Gujarāt. They usually abstain from smoking, and until recently have made widows shave their heads; but this rule is perhaps now relaxed. As a rule they are well educated, and the majority of them look to Government service for a career, either as clerks in the public offices or as officers of the executive and judicial services. They are intelligent and generally reliable workers. The full name of a Marātha or Gujarāti Brāhman consists of his own name, his father’s name and a surname. But he is commonly addressed by his own name, followed by the honorific termination Rao for Rāja, a king, or Pant for Pandit, a wise man.