полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 2

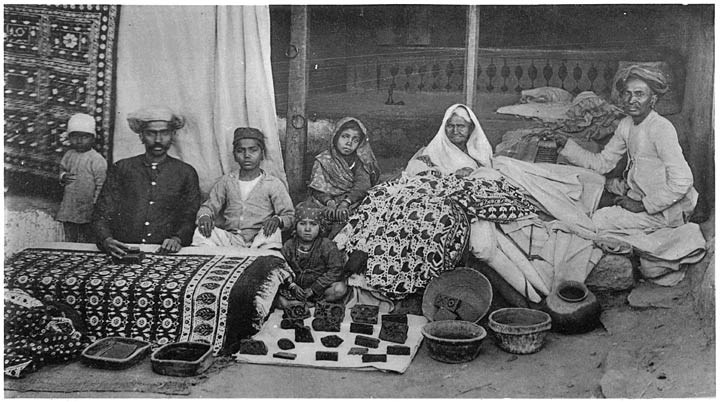

Chhīpa or calico-printer at work.

3. Caste subdivisions.

The caste have a number of subdivisions, such as the Malaiyas or immigrants from Mālwa, the Gujrāti who come from Gujarāt, the Golias or those who dye cloth with goli ka rang, the fugitive aniline dyes, the Nāmdeos who belong to the sect founded by the Darzi or tailor of that name, and the Khatris, these last being members of the Khatri caste who have adopted the profession.

4. Marriage and other customs.

Marriage is forbidden between persons so closely connected as to have a common ancestor in the third generation. In Bhandāra it is obligatory on all members of the caste, who know the bride or bridegroom, to ask him or her to dine. The marriage rite is that prevalent among the Hindustāni castes, of walking round the sacred post. Divorce and the marriage of widows are permitted. In Narsinghpur, when a bachelor marries a widow, he first goes through a mock ceremony by walking seven times round an earthen vessel filled with cakes; this rite being known as Langra Biyāh or the lame marriage. The caste burn their dead, placing the head to the north. On the day of Dasahra the Chhīpas worship their wooden stamps, first washing them and then making an offering to them of a cocoanut, flowers and an image consisting of a bottle-gourd standing on four sticks, which is considered to represent a goat. The Chhīpas rank with the lower artisan castes, from whose hands Brāhmans will not take water. Nevertheless some of them wear the sacred thread and place sect-marks on their foreheads.

5. Occupation.

The bulk of the Chhīpas dye cloths in red, blue or black, with ornamental patterns picked out on them in black and white. Formerly their principal agent was the al or Indian mulberry (Morinda citrifolia), from which a rich red dye is obtained. But this indigenous product has been ousted by alizarin, a colouring agent made from coal-tar, which is imported from Germany, and is about thirty per cent cheaper than the native dye. Chhīpas prepare sarīs or women’s wearing-cloths, and floor and bed cloths. The dye stamps are made of teakwood by an ordinary carpenter, the flat surface of the wood being hollowed out so as to leave ridges which form either a design in curved lines or the outlines of the figures of men, elephants and tigers. There is a great variety of patterns, as many as three hundred stamps having been found in one Chhīpa’s shop. The stamps are usually covered with a black ink made of sulphate of iron, and this is fixed by myrobalans; the Nīlgars usually dye a plain blue with indigotin. No great variety or brilliancy of colours is obtained by the Hindu dyers, who are much excelled in this branch of the art by the Muhammadan Rangrez. In Gujarāt dyeing is strictly forbidden by the caste rules of the Chhīpas or Bhaosars during the four rainy months, because the slaughter of insects in the dyeing vat adds to the evil and ill-luck of that sunless time.472

Chitāri

1. Origin and traditions.

Chitāri, Chiter, Chitrakār, Mahārana.—A caste of painters on wood and plaster. Chiter is the Hindustāni, and Chitāri the Marāthi name, both being corruptions of the Sanskrit Chitrakār. Mahārana is the term used in the Uriya country, where the caste are also known as Phāl-Barhai, or a carpenter who only works on one side of the wood. Chitāri is further an occupational term applied to Mochis and Jīngars, or leather-workers, who have adopted the occupation of wall-painting, and there is no reason to doubt that the Chitāris were originally derived from the Mochis, though they have now a somewhat higher position. In Mandla the Chitrakārs and Jīngars are separate castes, and do not eat or intermarry with one another. Neither branch will take water from the Mochis, who make shoes, and some Chitrakārs even refuse to touch them. They say that the founder of their caste was Biskarma,473 the first painter, and that their ancestors were Rājpūts, whose country was taken by Akbar. As they were without occupation Akbar then assigned to them the business of making saddles and bridles for his cavalry and scabbards for their swords. It is not unlikely that the Jīngar caste did really originate or first become differentiated from the Mochis and Chamārs in Rājputāna owing to the demand for such articles, and this would account for the Mochis and Jīngars having adopted Rājpūt names for their sections, and making a claim to Rājpūt descent. The Chitrakārs of Mandla say that their ancestors belonged to Garha, near Jubbulpore, where the tomb of a woman of their family who became sati is still to be seen. Garha, which was once the seat of an important Gond dynasty with a garrison, would also naturally have been a centre for their craft.

Another legend traces their origin from Chitrarekha, a nymph who was skilled in painting and magic. She was the friend of a princess Usha, whose father was king of Sohāgpur in Hoshangābād. Usha fell in love with a beautiful young prince whom she saw in a dream, and Chitrarekha drew the portraits of many gods and men for her, until finally Usha recognised the youth of her dream in the portrait of Aniruddha, the grandson of Krishna. Chitrarekha then by her magic power brought Aniruddha to Usha, but when her father found him in the palace he bound him and kept him in prison. On this Krishna appeared and rescued his grandson, and taking Usha from her father married them to each other. The Chitāris say that as a reward to Chitrarekha, Krishna promised her that her descendants should never be in want, and hence members of their caste do not lack for food even in famine time.474 The Chitāris are declining in numbers, as their paintings are no longer in demand, the people preferring the cheap coloured prints imported from Germany and England.

2. Social customs.

The caste is a mixed occupational group, and those of Marātha, Telugu and Hindustāni extraction marry among themselves. A few wear the sacred thread, and abstain from eating flesh or drinking liquor, while the bulk of them do not observe these restrictions.

Among the Jīngars women accompany the marriage procession, but not with the Chitāris.

Widow-marriage is allowed, but among the Mahārānas a wife who has lived with her husband may not marry any one except his younger brother, and if there are none she must remain a widow. In Mandla, if a widow marries her younger brother-in-law, half her first husband’s property goes to him finally, and half to the first husband’s children. If she marries an outsider she takes her first husband’s property and children with her. Formerly if a wife misbehaved the Chitāri sometimes sold her to the highest bidder, but this custom has fallen into abeyance, and now if a man divorces his wife her father usually repays to him the expenses of his marriage. These he realises in turn from any man who takes his daughter. A second wife worships the spirit of the dead first wife on the day of Akhātij, offering some food and a breast-cloth, so that the spirit may not trouble her.

3. Birth and childhood.

A pregnant woman must stay indoors during an eclipse; if she goes out and sees it they believe that her child will be born deformed. They think that a woman in this condition must be given any food which she takes a fancy for, so far as may be practicable, as to thwart her desires would affect the health of the child. Women in this condition sometimes have a craving for eating earth; then they will eat either the scrapings or whitewash from the walls, or black clay soil, or the ashes of cowdung cakes to the extent of a small handful a day. A woman’s first child should be born in her father-in-law’s or husband’s house if possible, but at any rate not in her father’s house. And if she should be taken with the pangs of travail while on a visit to her own family, they will send her to some other house for her child to be born. The ears of boys and the ears and nostrils of girls are pierced, and until this is done they are not considered to be proper members of the caste and can take food from any one’s hand. The Chitāris of Mandla permit a boy to do this until he is married. A child’s hair is not shaved when it is born, but this should be done once before it is three years old, whether it be a boy or girl. After this the hair may be allowed to grow, and shaved off or simply cut as they prefer. Except in the case of illness a girl’s hair is only shaved once, and that of an adult woman is never cut, unless she becomes a widow and makes a pilgrimage to a sacred place, when it is shaved off as an offering.

4. The evil eye.

In order to avert the evil eye they hang round a child’s neck a nut called bajar-battu, the shell of which they say will crack and open if any one casts the evil eye on the child. If it is placed in milk the two parts will come together again. They also think that the nut attracts the evil eye and absorbs its effect, and the child is therefore not injured. If they think that some one has cast the evil eye on a child, they say a charm, ‘Ishwar, Gauri, Pārvati ke ān nazar dur ho jao,’ or ‘Depart, Evil Eye, in the name of Mahādeo and Pārvati,’ and as they say this they blow on the child three times; or they take some salt, chillies and mustard in their hand and wave it round the child’s head and say, ‘Telin kī lāgi ho, Tamolin kī lāgi ho, Marārin kī ho, Gorania (Gondin) kī ho, oke, oke, parparāke phut jāwe,’ ‘If it be a Telin, Tambolin, Marārin or Gondin who has cast the evil eye, may her eyes crack and fall out.’ And at the same time they throw the mustard, chillies and salt on the fire so that the eyes of her who cast the evil eye may crack and fall out as these things crackle in the fire.

If tiger’s claws are used for an amulet, the points must be turned outwards. If any one intends to wish luck to a child, he says, ‘Tori balayān leun,’ and waves his hands round the child’s head several times to signify that he takes upon himself all the misfortunes which are to happen to the child. Then he presses the knuckles of his hands against the sides of his own head till they crack, which is a lucky omen, averting calamity. If the knuckles do not crack at the first attempt, it is repeated two or three times. When a man sneezes he will say ‘Chatrapati,’ which is considered to be a name of Devi, but is only used on this occasion. But some say nothing. After yawning they snap their fingers, the object of which, they say, is to drive away sleep, as otherwise the desire will become infectious and attack others present. But if a child yawns they sometimes hold one of their hands in front of his mouth, and it is probable that the original meaning of the custom was to prevent evil spirits from entering through the widely opened mouth, or the yawner’s own soul or spirit from escaping; and the habit of holding the hand before the mouth from politeness when yawning inadvertently may be a reminiscence of this.

5. Cradle-songs.

The following are some cradle-songs taken down from a Chitrakār, but probably used by most of the lower Hindu castes:

1. Mother, rock the cradle of your pretty child. What is the cradle made of, and what are its tassels made of?The cradle is made of sandalwood, its tassels are of silk.Some Gaolin (milkwoman) has overlooked the child, he vomits up his milk.Dasoda475 shall wave salt and mustard round his head, and he shall play in my lap.My baby is making little steps. O Sunār, bring him tinkling anklets!The Sunār shall bring anklets for him, and my child will go to the garden and there we will eat oranges and lemons.2. My Krishna’s tassel is lost, Tell me, some one, where it is. My child is angry and will not come into my arms.The tears are falling from his eyes like blossoms from the bela476 flower.He has bangles on his wrists and anklets on his feet, on his head a golden crown and round his waist a silver chain.The jhumri or tassel referred to above is a tassel adorned with cowries and hung from the top of the cradle so that the child may keep his eyes on it while the cradle is being rocked.

3. Sleep, sleep, my little baby; I will wave my hands round your head477 on the banks of the Jumna. I have cooked hot cakes for you and put butter in them; all the night you lay awake, now take your fill of sleep.The little mangoes are hanging on the tree; the rope is in the well; sleep thou till I go and come back with water.I will hang your cradle on the banyan tree, and its rope to the pīpal tree; I will rock my darling gently so that the rope shall never break.The last song may be given in the vernacular as a specimen:

4. Rām kī Chireya, Rām ko khet.Khaori Chireya, bhar, bhar pet.Tan munaiyān khā lao khet,Agao, labra, gāli det;Kahe ko, labra, gāli de;Apni bhuntia gin, gin le.or—

The field is Rāma’s, the little birds are Rāma’s; O birds, eat your fill; the little birds have eaten up the corn.The surly farmer has come to the field and scolds them; the little birds say, ‘O farmer, why do you scold us? count your ears of maize, they are all there.’This song commemorates a favourite incident in the life of Tulsi Dās, the author of the Rāmāyana, who when he was a little boy was once sent by his guru to watch the crop. But after some time the guru came and found the field full of birds eating the corn and Tulsi Dās watching them. When asked why he did not scare them away, he said, ‘Are they not as much the creatures of Rāma as I am? how should I deprive them of food?’

6. Occupation.

The Chitāris pursue their old trade, principally in Nāgpur city, where the taste for wall-paintings still survives; and they decorate the walls of houses with their crude red and blue colours. But they have now a number of other avocations. They paint pictures on paper, making their colours from the tins of imported aniline dyeing-powders which are sold in the bazar; but there is little demand for these. They make small pictures of the deities which the people hang on their walls for a day and then throw away. They also paint the bodies of the men who pretend to be tigers at the Muharram festival, for which they charge a rupee. They make the clay paper-covered masks of monkeys and demons worn by actors who play the Rāmlīla or story of Rāma on the Rāmnaomi festival in Chait (March); they also make the tāzias or representations of the tomb of Hussain and paper figures of human beings with small clay heads, which are carried in the Muharram procession. They make marriage crowns; the frames of these are of conical shape with a half-moon at the top, made from strips of bamboo; they are covered with red paper picked out with yellow and green and with tinfoil, and are ornamented with borders of date-palm leaves. The crowns cost from four annas to a rupee each. They make the artificial flowers used at weddings; these are stuck on a bamboo stick and at the arrival and departure of the bridegroom are scrambled for by the guests, who take them home as keepsakes or give them to their children for playthings. The flowers copied are the lotus, rose and chrysanthemum, and the imitations are quite good. Sometimes the bridegroom is surrounded by trays or boxes of flowers, carried in procession and arranged so as to look as if they were planted in beds. Other articles made by the Chitrakār are paper fans, paper globes for hanging to the roofs of houses, Chinese lanterns made either of paper or of mica covered with paper, and small caps of velvet embroidered with gold lace. At the Akti festival478 they make pairs of little clay dolls, dressing them as male and female, and sell them in red lacquered bamboo baskets, and the girls take them to the jungle and pretend that they are married. Formerly the Chitrakārs made clay idols for temples, but these have been supplanted by marble images imported from Jaipur. The Jīngars make the cloth saddles on which natives ride, and some of them bind books, the leather for which is made from goat-skin, and is not considered so impure as that made from the hides of cattle. But one class of them, who are considered inferior, make leather harness from cow-hide and buffalo-hide.

Chitrakathi

Chitrakathi, Hardas. 479—A small caste of religious mendicants and picture showmen in the Marātha Districts. In 1901 they numbered 200 persons in the Central Provinces and 1500 in Berār, being principally found in the Amraoti District. The name, Mr. Enthoven writes,480 is derived from chitra, a picture, and katha, a story, and the professional occupation of the caste is to travel about exhibiting pictures of heroes and gods, and telling stories about them. The community is probably of mixed functional origin, for in Bombay they have exogamous section-names taken from those of the Marāthas, as Jādhow, More, Powār and so on, while in the Central Provinces and Berār an entirely different set is found. Here several sections appear to be named after certain offices held or functions performed by their members at the caste feasts. Thus the Atak section are the caste headmen; the Mānkari appear to be a sort of substitute for the Atak or their grand viziers, the word Mānkar being primarily a title applied to Marātha noblemen, who held an official position at court; the Bhojni section serve the food at marriage and other ceremonies; the Kākra arrange for the lighting; the Kothārya are store-keepers; and the Ghoderao (from ghoda, a horse) have the duty of looking after the horses and bullock-carts of the castemen who assemble. The Chitrakathis are really no doubt the same caste as the Chitāris or Chitrakārs (painters) of the Central Provinces, and, like them, a branch of the Mochis (tanners), and originally derived from the Chamārs. But as the Berār Chitrakathis are migratory instead of settled, and in other respects differ from the Chitāris, they are treated in a separate article. Marriage within the section is forbidden, and, besides this, members of the Atak and Mānkari sections cannot intermarry as they are considered to be related, being divisions of one original section. The social customs of the caste resemble those of the Kunbis, but they bury their dead in a sitting posture, with the face to the east, and on the eighth day erect a platform over the grave. At the festival of Akhatīj (3rd of light Baisākh)481 they worship a vessel of water in honour of their dead ancestors, and in Kunwār (September) they offer oblations to them. Though not impure, the caste occupy a low social position, and are said to prostitute their married women and tolerate sexual licence on the part of unmarried girls. Mr. Kitts482 describes them as “Wandering mendicants, sometimes suspected of associating with Kaikāris for purposes of crime; but they seem nevertheless to be a comparatively harmless people. They travel about in little huts like those used by the Waddars; the men occasionally sell buffaloes and milk; the women beg, singing and accompanying themselves on the thāli. The old men also beg, carrying a flag in their hand, and shouting the name of their god, Hari Vithal (from which they derive their name of Hardās). They are fond of spirits, and, when drunk, become pot-valiant and troublesome.” The thāli or plate on which their women play is also known as sarthāda, and consists of a small brass dish coated with wax in the centre; this is held on the thigh and a pointed stick is moved in a circle so as to produce a droning sound. The men sometimes paint their own pictures, and in Bombay they have a caste rule that every Chitrakathi must have in his house a complete set of sacred pictures; this usually includes forty representations of Rāma’s life, thirty-five of that of the sons of Arjun, forty of the Pāndavas, forty of Sīta and Rāwan, and forty of Harishchandra. The men also have sets of puppets representing the above and other deities, and enact scenes with them like a Punch and Judy show, sometimes aided by ventriloquism.

Cutchi

1. General notice.

Cutchi or Meman, Kachhi, Muamin.—A class of Muhammadan merchants who come every year from Gujarāt and Cutch to trade in the towns of the Central Provinces, where they reside for eight months, returning to their houses during the four months of the rainy season. In 1911 they numbered about 2000 persons, of whom five-sixths were men, this fact indicating the temporary nature of their settlements. Nevertheless a large proportion of the trade of the Province is in their hands. The caste is fully and excellently described by Khān Bahādur Fazalullah Lutfullah Farīdi, Assistant Collector of Customs, Bombay, in the Bombay Gazetteer.483 He remarks of them: “As shopkeepers and miscellaneous dealers Cutchis are considered to be the most successful of Muhammadans. They owe their success in commerce to their freedom from display and their close and personal attention to and keen interest in business. The richest Meman merchant does not disdain to do what a Pārsi in his position would leave to his clerks. Their hope and courage are also excellent endowments. They engage without fear in any promising new branch of trade and are daring in their ventures, a trait partly inherited from their Lohāna ancestors, and partly due to their faith in the luck which the favour of their saints secures them.” Another great advantage arises from their method of trading in small corporations or companies of a number of persons either relations or friends. Some of these will have shops in the great centres of trade, Bombay and Calcutta, and others in different places in the interior. Each member then acts as correspondent and agent for all the others, and puts what business he can in their way. Many are also employed as assistants and servants in the shops; but at the end of the season, when all return to their native Gujarāt, the profits from the different shops are pooled and divided among the members in varying proportion. By this method they obtain all the advantages which are recognised as attaching to co-operative trading.

2. Origin of the caste.

According to Mr. Farīdi, from whose description the remainder of this article is mainly taken, the Memans or more correctly Muamins or ‘Believers’ are converts from the Hindu caste of Lohānas of Sind. They venerate especially Maulāna Abdul Kādir Gīlāni who died at Baghdād in A.D. 1165. His sixth descendant, Syed Yūsufuddīn Kordiri, was in 1421 instructed in a dream to proceed to Sind and guide its people into the way of Islām. On his arrival he was received with honour by the local king, who was converted, and the ruler’s example was followed by one Mānikji, the head of one of the nukhs or clans of the Lohāna community. He with his three sons and seven hundred families of the caste embraced Islām, and on their conversion the title of Muamin or ‘Believer’ was conferred on them by the saint. It may be noted that Colonel Tod derives the Lohānas from the Rājpūts, remarking of them:484 “This tribe is numerous both in Dhāt and Talpūra; formerly they were Rājpūts, but betaking themselves to commerce have fallen into the third class. They are scribes and shopkeepers, and object to no occupation that will bring a subsistence; and as to food, to use the expressive idiom of this region where hunger spurns at law, ‘Excepting their cats and their cows they will eat anything.’” In his account of Sind, Postans says of the Lohānas: “The Hindu merchants and bankers have agents in the most remote parts of Central Asia and could negotiate bills upon Candahār, Khelāt, Cābul, Khiva, Herāt, Bokhāra or any other marts of that country. These agents, in the pursuit of their calling, leave Sind for many years, quitting their families to locate themselves among the most savage and intolerant tribes.” This account could equally apply to the Khatris, who also travel over Central Asia, as shown in the article on that caste; and if, as seems not improbable, the Lohānas and Khatris are connected, the hypothesis that the former, like the latter, are derived from Rājpūts would receive some support.

The present Pīr or head of the community is Sayyid Jāfir Shāh, who is nineteenth in descent from Yūsufuddīn and lives partly in Bombay and partly in Mundra of South Cutch. “At an uncertain date,” Mr. Farīdi continues, “the Lohāna or Cutchi Memans passed from Cutch south through Kāthiāwār to Gujarāt. They are said to have been strong and wealthy in Surat during the period of its prosperity (1580–1680). As Surat sank the Cutchi Memans moved to Bombay. Outside Cutch and Kāthiāwār, which may be considered their homes, the Memans are scattered over the cities of north and south Gujarāt and other Districts of Bombay. Beyond that Presidency they have spread as traders and merchants and formed settlements in Calcutta, Madras, the Malabar Coast, South Burma, Siam, Singapore and Java; in the ports of the Arabian Peninsula, except Muscat, where they have been ousted by the Khojas; and in Mozambique, Zanzibar and the East African Coast.”485 They have two divisions in Bombay, known as Cutchi or Kachhi and Halai.