полная версия

полная версияThe Fiction Factory

The year, which opened auspiciously and proved a banner year financially, closed with a discontinuance of all orders from Harte & Perkins. Re-prints were being used in the old Five-Cent Library – stories that had been issued years before and could now be republished for another generation of boy readers. Under date of Dec. 1, 1911, Mr. Perkins wrote:

"I know of nothing, just at present, which you can do for us, but should anything develop I shall be very glad to inform you."

This left Edwards with a sketch a month for the trade paper, for which he was paid $10 each. That "misfortunes never come singly" is an old saying, and one which Edwards has found particularly true in the writing profession. A letter of Dec. 27, informed him:

"We have decided to dispense with the sketches in our trade paper for the present, at least; therefore the February sketch we have in hand will be the last we will want unless we give you further notice."

In a good many cases the tendency of a writer, when fate deals hardly with him in the matter of a demand for his work, is to take his rebuffs too seriously. Often he will lock up his Factory, leaving a placard on the door: "Closed. Proprietor gone to Halifax. Nothing in the fiction game anyhow."

Edwards used to feel in this way. As he grew older he learned to take his disappointments with more or less equanimity, and to keep the Factory running. He thought, now, of Mr. White and The Argosy. Here was a good time to prepare an Argosy serial. He wrote it, sent it, and on Feb. 15, 1901, received this terse letter:

"My dear Mr. Edwards:

We can use your story, 'The Tangle in Butte,' in The Argosy at $200. Very truly yours,

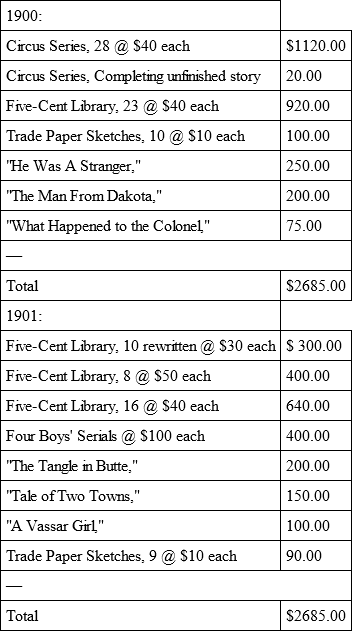

Matthew White, Jr."This was less than the price paid for "He Was A Stranger," but the story ran only 60,000 words, while the other serial had gone to 100,000. The acceptance went to Mr. White by return mail.

On the day following there came a letter from Harte & Perkins ordering work in the old Five-Cent Library – work that would keep Edwards busy for the rest of the year. Ten of the old stories which Edwards had written were to be revised and lengthened by 10,000 words. For this work he was to be paid $30 for each story. When the ten numbers had been revised and lengthened, he was to go on with the stories, writing a new one each week. Fifty dollars apiece was to be paid for the new stories.

There was an order, too, for more sketches for the trade paper, to be done in another vein.

On Aug. 5 the length of the Five-Cent Library stories was cut from 30,000 words to 20,000, and the remuneration was cut from $50 to $40. Another juvenile paper was started and Edwards was asked to submit serials for it. In fact, 1901 might be called a "boom" year for the Fiction Factory, although the returns, while satisfactory, were not of the "boom" variety.

Perhaps the reader may remember the serial, "A Vassar Girl," referred to in a previous chapter as having been submitted to Harte & Perkins and rejected. Edwards had faith in this story and offered it to Mr. White. Mr. White's judgment, however, tallied with that of Harte & Perkins. Under date of June 13 Mr. White wrote:

"I am sorry that 'A Vassar Girl' has not borne out the promise of the opening chapters. The interest in it is not sufficiently sustained for serial use. The story might be divided into several incidents, which do not grow inevitably the one out of the other. For this reason it has, as a whole, proved disappointing and I am returning the manuscript by express. We should be glad, however, to have you continue to submit work to us."

With faith undiminished, Edwards forwarded the story to McClure's Newspaper Syndicate. It was returned without an explanation of any kind. Again he prevailed upon Harte & Perkins to consider it. It came back from them on Sept. 13, with this message:

"I am sorry to say that we do not feel inclined to revise our judgement with reference to your manuscript story, 'A Vassar Girl.' I am inclined to think from looking over the review of the story that it would be well for you to sell it just as it is, and we hope you will be able to find a market for it somewhere. It would not pay us to publish."

Edwards knew that the story, wrought out of his Arizona experiences, was true in local color and good of its kind, and he failed to understand why it was not appreciated. Then, on Sep. 14, came this from the S. S. McClure Company:

"During July we had under consideration a story of yours entitled, 'A Vassar Girl.' On July 31 we wrote you from the Syndicate, informing you that we hoped to be able to use the story as a serial in the very near future. The serial was taken back for consideration in the book department by one of the readers who wished again to examine it, and from there it was erroneously returned to you. Now if you have not disposed of the serial rights of 'A Vassar Girl' we should like you again to forward the story to us, and we will submit it to some of our papers as we had always intended to do. We will then give you a prompt decision."

The story was purchased, and Edwards' faith in it was confirmed.

It was during this year of 1901 that Edwards had a fleeting glimpse of fortune as a playwright. His story, "The Tangle in Butte," had been read by an actor, a leading man in a Kansas City stock company, who wanted dramatic rights so that he might have a play taken from it and written around him. Edwards proposed to write the play himself. He did so, and was promptly offered $5,000 for the play, payable in installments after production. Following a good deal of correspondence it was decided to put on the piece for a week's try-out in Kansas City. Edwards waived his right to royalties for the week, models of the scenery were made, rehearsals began – and then the actor was suddenly stricken with a serious illness and the deal was off. When he had recovered sufficiently to travel he went East, taking the play with him. For several months he tried to interest various managers in it, but without effect.

The year 1901 closed for Edwards with the sketches for the trade paper no longer in demand; but, otherwise, he faced a steadily brightening prospect for the Fiction Factory.

Poeta nascitur; non fit. This has been somewhat freely translated by one who should know, as "The poet is born; not paid."

XV

FROM THE

FACTORY'S FILES

A letter of commendation from the reader of a story to the writer is not only a pleasant thing in itself but it proves the reader a person of noble soul and high motives. Noblesse oblige!

The writer who loves his work is not of a sordid nature. The check an editor sends him for his story is the smallest part of his reward. His has been the joy to create, to see a thought take form and amplify under the spell of his inspiration. A joy which is scarcely less is to know that his work has been appreciated by others.

A letter like the one below, for instance, not only gives pleasure to the recipient but at the same time fires a writer with determination never to let his work fall short of a previous performance. This reader's good will he must keep, at all hazards.

"Wayland, N. Y., March 22nd, 1905.Mr. John Milton Edwards,

Care The F. A. Munsey Co., New York.

My dear Sir:

I read the story in this last Argosy, entitled 'Fate and the Figure Seven,' and was in a way considering if it were possible that a man could act in the subconscious state you picture. Deem my surprise, last night, when I read of a similar case in the report of the Brockton accident.

In case you should have failed to notice this item, I send you a clipping from a Buffalo paper.

I WISH INCIDENTALLY TO THANK YOU FOR YOUR SHARE IN MAKING LIFE PLEASANT FOR ME. I have enjoyed your works immensely from time to time on account of their decidedly original ideas. They are always refreshingly out of the ordinary rut.

Yours truly,A. F. V – ."There is one sentence in this letter which Edwards has put in capitals. If possible, he would have written it in letters of gold. In this little world, so crowded with sorrow and tragedy, what is it worth to have had a share in making life pleasant for a stranger? To Edwards it has been worth infinitely more than he received for "Fate and the Figure Seven."

Another letter carries an equally pleasant message:

"Livingstone, Montana, Sep. 16, 1903.Mr. John Milton Edwards,

Care The Argosy, New York City.

Dear Sir:

Having read your former stories in The Argosy on Arizona, and last night having commenced 'The Grains of Gold,' I trust you will pardon my expression of appreciation of said stories. I lived ten years in Arizona as private secretary to several of the Federal Judges, and also lived in Mexico, and am still familiar with conditions in that section.

I have enjoyed most keenly your handling of thrilling scenes on Arizona soil. It is an exasperation that they appear in serial form, as I dislike the month's interval.

My only purpose in writing is to express my admiration of your plots and local color, and I remain,

Sincerely yours,Richard S. S – ."Edwards has always prided himself on keeping true to the actual conditions of the country which forms the screen against which his plot and characters are thrown. This is a gratifying tribute, therefore, from one who knows.

A letter which rather startled Edwards, suggesting as it did the Maricopa Indian incident which trailed upon the heels of "A Study in Red," is this:

"Colorado Springs, Colo., 2-25-'09.Mr. John Milton Edwards,

Dear Sir: Through the kindness of the editor of the Blue Book I received your address. I am very much interested in your story entitled, 'Country Rock at Kish-Kish,' and know the greater part of it to be true to life, but would like to know if it is ALL true. Did Sager have a daughter? And where did Sager go when he left Arizona? Or is that just a part of the story? I am very much interested in that character, Sager. Can you tell me if he is still living, and where? Any information that you may be able to give me will be more than appreciated.

Thanking you in advance for the favor, I am,

Yours respectfully,Mrs. James R. S – ."Edwards answered this letter – he answers promptly all such letters that come to him and esteems it a privilege – and received a reply. It appeared that Mrs. S – was the grand-daughter of a man whom "Sager" had robbed of a large amount of money. "Country Rock at Kish-Kish" was built on a newspaper clipping twenty years old. This clipping Edwards forwarded to Mrs. S – in the hope that it might help her in her quest for "Sager." The letter was returned as uncalled for. Should this ever fall under the eye of Mrs. S – she will understand that Edwards did everything in his power to be of assistance to her.

Now and again a letter, which compliments an author indirectly, will chasten his mounting spirit with the reminder of a "slip:"

"Rochester, N. Y., Nov. 17, 1905.Mr. John Milton Edwards:

Dear Sir: – Will you please tell me where I can get more of your stories than in the Argosy; and also, in reference to your story which concludes in December Argosy, how many large autos were in use in New York in 1892?

Yours respectfully,Howard Z – ."Carelessness in a writer is inexcusable. It is the one thing which a reader will not forgive, for it is very apt to spoil his pleasure in what would otherwise have been a good story. This is a sublimated form of the "gold-brick game," inasmuch as the reader pays his money for a magazine only to find that he has been "buncoed" by the table of contents. If there is a flaw in the factory's product, rest assured that it will be discovered and react to the disadvantage of everything else that comes from the same mill.

Many readers will be found whose interest in a writer's work is so keen that they are tempted to offer suggestions. Such suggestions are not to be lightly considered. Magazines are published to please their readers, and they are successful in a direct ratio with their ability to accomplish this end. Naturally, the old doggerel concerning "many men of many minds" will apply here, and a single suggestion that has not a wide appeal, or that fails to conform to the policy of the magazine, must be handled with great care.

"Cincinnati, Ohio, Oct. 31, 1905.Mr. John Milton Edwards,

Care Frank A. Munsey Co.,

New York.

Dear Sir:

Because of the increasing interest in Socialism, would it not be a good idea to write a story showing under what conditions we should live in, say, the year 2,000, if the Socialists should come into power?

You might begin your story with the United States under a Socialistic form of government, and later on Socialize the rest of the world.

Your imaginative stories are the ones most eagerly sought in the pages of The Argosy, and I think that a story such as I have suggested would serve to increase your popularity among the readers of fiction.

Sincerely yours,J. H. S – ."It frequently happens that a comedian will get after a writer with a stuffed club or a slapstick. Some anonymous humorist, upon reading a story of Edwards' in The Argosy, labored and brought forth the following:

"November 19, 1904.John Milton Edwards,

Care Frank A. Munsey Co.,

New York.

My dear John: —

I have read with much pleasure and delight the first six chapters of your latest story, 'At Large in Terra Incognita,' as published in the December number of The Argosy.

I cannot understand why you failed to send me the proof-sheets of this story for correction, as you did with 'There and Back.' It is evident so far as I have read the person who corrected your proof-sheets was as ignorant as yourself.

Where you got the material for this story is not within my memory, retrospective though it is, and I am sure you must have been on one of your periodical drunks, otherwise the flights of fancy you have taken would have been more rational and not so far removed beyond the pale of the human intellect.

Now, my dear John, I beg of you to give up going on these habitual tears, because you are not only ruining your constitution but your reputation as a writer is having reflections cast upon it. I trust you will not take this letter as a sermon but rather in a spirit of friendly counsel.

I hope you will send me at once the remaining chapters of this great 'At Large in Terra Incognita.'

Your Nemesis,Theo. Roosenfeldt,Pres't Trust-Busters' Asso."Readers have usually the courage of their convictions and not many anonymous letters find their way into the office of the Fiction Factory. Edwards remembers one other letter which was signed "Biff A. Hiram." At that time Edwards did not know Mr. Biff A. Hiram from Adam, but he has since made the gentleman's acquaintance, and discovered how wide is his circle of friends.

If praise from a reader has a tendency to exalt, then how much more of the flattering unction may a writer lay to his soul when approval comes from a brother or sister of the pen? With such a letter, this brief symposium from the Factory files may be brought to a close.

"Mr. John Milton Edwards,

Dear Sir: —

Allow me to congratulate you upon your success with the novelette in a recent issue of the Blue Book. It is to my mind the BEST short story of its kind I have EVER read. As I try to write short stories I see its merits doubly. The modelling is splendid. Will you pardon my display of interest?

Very truly yours,K. B – ."Rules for Authors.

Dr. Edward Everett Hale, author of "The Man without a Country," and other notable books, gives a few rules which are of interest to the author and the journalist. Dr. Hale's success in the literary world makes these rules, gleaned from the field of experience, especially valuable to young writers:

1. Know what you want to say.

2. Say it.

3. Use your own language.

4. Leave out all fine phrases.

5. A short word is better than a long one.

6. The fewer words, other things being equal, the better.

7. Cut it to pieces – which means revise, revise, revise.

XVI

GROWING

PROSPERITY

The years 1902 and 1903 were busier years than ever for the Fiction Factory. Nineteen-two is to be remembered particularly for opening a new departure in the story line in The Argosy, and for placing the first book with the G. W. Dillingham Company. Nineteen-three claims distinction for seeing the book brought out and for boosting the Factory returns beyond the three-thousand-dollar mark. But it must not be inferred that the book had very much to do with this. Edwards' royalties for the year were less than $100.

In September, 1902, Edwards made one of his customary "prospecting" trips to New York. If there was anything in omens his stay in the city promised dire things. On the second day after his arrival he went to Coney Island with a friend. Together they called on the seventh son of a seventh son and had their palms read. The dispenser of occult knowledge assured Edwards that the future was very bright, that Tuesday was his lucky day and that Spring was the best time for him to consummate his business undertakings. That day, as it happened, was Tuesday. In the teeth of this promising augury, and within ten minutes after leaving the palmist's booth, some Coney Island "dip" shattered Edwards' confidence in Tuesday by annexing his wallet. The wallet, as it happened, contained all the money Edwards had brought from home, with the exception of a little loose change.

This was the second time Edwards had been all but stranded in the Metropolis, and this time the stranding was more complete. When he cast up accounts that evening he found himself with a cash balance of $1.63. Fortunately Mrs. Edwards was not along. He had left her at home with the understanding that she was to come on later. When a writer has come within hailing distance of the bread line there remains but one thing to do, and that is to start the Factory going with day and night shifts.

Edwards called on Mr. White, of The Argosy, and outlined a serial story. He was told to go ahead with it. For five days Edwards hardly stirred from his room. At the end of that time he had completed "The Desperado's Understudy," and had sold it to Mr. White for $250, spot cash.

After completing this serial, Edwards outlined to Mr. White a novelette which would furnish The Argosy with something new in the fiction line. The plot was based on a musical extravaganza which he had written, several years before, in collaboration with Mr. Eugene Kaeuffer, at one time connected with The Bostonians. Nothing had ever come of this ambitious effort, although book and musical score were completed and offered to Mr. McDonald of The Bostonians and to Mr. Thomas Q. Seabrooke. Mr. White liked the idea of the story immensely and gave Edwards carte blanche to go ahead with it.

This story, "Ninety, North," paved the way for other fantastic yarns which made a decided hit in The Argosy and so pointed Edwards along a fresh line of endeavor which proved as congenial as it was profitable.

Several months before he visited New York Edwards had sold to The McClure Syndicate, a juvenile serial which may be referred to here as "The Campaign at Topeka." For this he had been offered $200, which offer he promptly accepted. He had not received a check, however, and was at a loss to understand the reason. To this day the reason remains obscure, although later events pointed to a misunderstanding of some kind regarding the story between the Syndicate and one of its readers. Before Edwards left New York he was paid the $200. More than a year afterward he was informed that the serial had been sold to the Century Company for St. Nicholas, and that after publication in that magazine it was to be brought out in book form.

It was Mr. T. C. McClure who put Edwards in touch with the Dillingham Company and referred him to them as prospective publishers, in cloth, of the successful Syndicate story, "A Tale of Two Towns." Edwards submitted galley proofs of the serial to Mr. Cook of the Dillingham Company, and ultimately signed a contract to have the book published on the usual royalty basis of ten per cent.

For Harte & Perkins, during the year, the Factory ground out nickel novels, juvenile serials, one sketch for the trade paper and a few detective stories. On Nov. 28, after he had returned home from New York, he was notified:

"Much as I regret to inform you of it, by a recent purchase of copyright stories we are placed in a position where we will not require any further material for any of our five-cent libraries for some time to come, so we must discontinue orders to you for all this material."

Edwards, in a way, had become hardened to messages of this kind. The Argosy was an anchor to windward, and he resolved to give his attention to serials for Mr. White. In December, 1902, and January and February, 1903, he wrote and forwarded "Ninety, North," a second fantastic story called "There and Back," and the Arizona serial "Grains of Gold." All three of these stories were sold at once, bringing in $700. In a letter dated Oct. 14, 1903, Mr. White had this to say about "There and Back:"

"Thanks for letting me see the enclosed letter regarding 'Ninety, North.' I am equally pleased with yourself at its significance. I am wondering whether you have heard much about your story 'There and Back?' My impression is that that has been one of the most popular stories you have ever written for The Argosy. When I see you I will tell you an odd little circumstance that occurred in connection with its run in the magazine."

The circumstances referred to by Mr. White took place in Paris. One of The Argosy's readers happened to be in a café, looking over proofs of a forthcoming installment of "There and Back" while at her luncheon, when she heard the story being discussed, in complimentary terms, by a number of Frenchmen at an adjoining table. Strange indeed that Frenchmen should be interested in an American story, and stranger still that The Argosy's reader should be reading an installment of the very same story while men in that foreign café were discussing it!

The first installment of "There and Back," Mr. White informed Edwards, had increased The Argosy's circulation seven thousand copies.8

On March 2 Harte & Perkins requested Edwards to continue work on the old Five-Cent Library. By taking up this work again he would be diminishing the Factory's serial output, but he reflected that his fertility in the matter of serials would soon have Mr. White over-supplied. Therefore Edwards decided to go on with the nickel weeklies.

In March, as Mr. MacLean of The Popular Magazine once put it, Edwards "came out in cloth," the Dillingham Company issuing "A Tale of Two Towns" on St. Patrick's Day.

What are the feelings of an author when he opens his first book for the first time? If you, dear reader, are yet to "get out in cloth" for the first time, then some day you will know. But, if you value your peace of mind, do not build too gorgeous an air castle on the foundation of this printed thing. Printed things are at the mercy of the reviewers and, in a larger sense, of the great reading public. The reviewers, in nearly every instance, were kind with "A Tale of Two Towns." In many quarters it was praised fulsomely, but the book did not strike that fickle sentiment called popular fancy. In six months, Mr. Cook, of the Dillingham Company, wrote Edwards that "A Tale of Two Towns" was "a dead duck." In the December settlement, however, the remains yielded royalties of $96.60. For two or three years the royalties trailed along, and finally the edition was wound up with a payment of $1.50. Sic transit gloria!

During January, 1903, a theatrical gentleman requested Edwards to dramatize a book which Messrs. Street & Smith had issued in paper covers. "You can change the title," the gentleman suggested, "and slightly change the incidents. In that way it won't be necessary to write Street & Smith for permission or, indeed, to let them know anything about it." Edwards knew, however, that nothing will so surely wreck a writer's prospects as playing fast and loose with editors and publishers. He refused to consider the theatrical gentleman's proposition. Instead, he forwarded his Argosy story, "The Desperado's Understudy," upon which Mr. White had given him dramatic rights, and offered to make a stage version of it. The offer was accepted and a play was built up from the story. The theatrical gentleman was pleased and said he would give $1,500 for the dramatization. Then, alas! the theatrical gentleman's company went on the rocks at the Alhambra Theatre, in Chicago, and Edwards had repeated his former playwriting experience.