полная версия

полная версияThe Fiction Factory

"We have received the first two installments of 'Won by Love' and like them very much indeed, but before giving you a definite answer we would like to have four more instalments on approval, making six in all. Kindly send these at your earliest convenience and oblige."

The four installments were sent and nothing more was heard from them until a telegram, dated Jan. 19, 1899, was received:

"Please send more of 'Won by Love' as soon as possible. Must have it Monday."

Owing to the fact that the writer of the old Five-Cent Library, for which Edwards had furnished copy some years before, had been taken seriously ill, this work had been turned over to Edwards on Dec. 27, 1898.

At this time Edwards was confined to his bed, and there he worked, his typewriter in front of him on an improvised table. He had just finished several hours' work on a library story when the telegram regarding "Won by Love" was received. This was Saturday. Edwards wired at once that he would send two more installments on the following Monday. These 12,000 words went forward according to schedule, and on the night they were sent the doctor called and found his patient in a state of collapse. Cause, too much "Won by Love." The young physician took it more to heart than Edwards did.

"I'm afraid," said he gloomily, "that you have ended your writing for all time."

"You're wrong, doctor," declared Edwards; "I'm not going to be removed until I've done something better than pot-boilers."

"I want to call a specialist into consultation," was the reply.

The specialist was called and Edwards was stripped and his body marked off into sections – mapped out with one medical eye on the "undiscovered country" and the other on this lowly but altogether lovely "vale of tears." When the examination was finished, the preponderance of testimony was all in favor of the Promised Land.

"I should say, Mr. Edwards," said the specialist, in a tone professionally sympathetic, "that you have one chance in three to get well. Your other chance is for possibly seven or eight years of life. The third chance allows you barely time to settle your affairs."

Settle his affairs! What affairs had Edwards to settle? There was the next library to be written and "Won by Love" to finish, but these would have netted Mrs. Edwards no more than $340. And the smallest chance would not suffer Edwards to leave his wife even this pittance. Since his disastrous Arizona experience Edwards had not been able to save any money. He was only just beginning to look ahead to a little garnering when the doctors pronounced their verdict. He had not a dollar of property, real or personal, if his library was not taken into account, and not a cent of life insurance. After turning this deplorable situation over in his mind, he decided that it was impossible for him to die.

"I'm going to take the first chance," said he, "and make the most of it."

He did. The young physician gave up more of his time and worked like a galley slave to see his patient through. Now, thirteen years after the specialist spoke the last word, Edwards is in robust health – the monument of his own determination and the young doctor's skill. Nothing succeeds – sometimes – like the logic of nil desperandum.

To regain a foothold with his publishers, following the disastrous year of 1897, had cost Edwards so much persistent work that he would not cancel a single order. He hired a stenographer and for two weeks dictated his stories, then again resumed the writing of them himself, in bed and with the use of the improvised table. Success awaited all his fiction, even when turned out in such adverse circumstances. This, perhaps, was the best tonic he could have. He improved slowly but surely and was able, in addition to his regular work, to write a hundred-thousand word novel embracing his Arizona experiences. This novel he called "He Was a Stranger."

The title was awkward, but it had been clipped from the quotation, "he was a stranger, and they took him in." The story was submitted to Harte & Perkins, but they were not in the mood for taking in strangers of that sort. But the year following the novel secured the friendly consideration of Mr. Matthew White, Jr., and introduced Edwards into the Munsey publications.

Another novel, "The Man from Dakota," was returned by Harte & Perkins after they had had it on hand for a year. It was declined in the face of a favorable report by one of their readers because, "We have so many books on hand that must be brought out during the next year that we cannot consider this story."

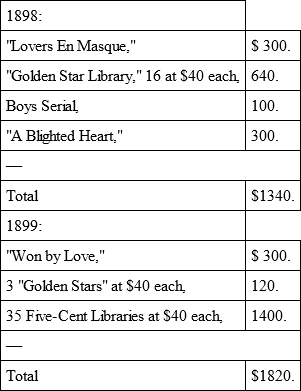

The year 1899 closed with Fortune's smile brightening delightfully for Edwards, and the new century beckoning him pleasantly onward with the hope of better things to come. The returns for the two years, standing to the credit of The Fiction Factory, are summarized thus:

Edwards lives in the outskirts of a small town, on a road much travelled by farmers. Two honest tillers of the soil were passing his home, one day, and one of them was heard to remark to the other: "A man by the name of Edwards lives there, Jake. He's one of those fictitious writers."

Edwards has few friends whom he prizes more highly than he does Col. W. F. Cody, "Buffalo Bill," and Major Gordon W. Lillie, "Pawnee Bill." While the Wild West and Far East Show, of which Cody and Lillie are the proprietors was making its farewell tour with the Last of the Scouts, Major Lillie had this to tell about Colonel Cody:

"You'd be surprised at the number of people who try to beat their way into the show by stringing the Colonel. The favorite way is by claiming acquaintance with him. A stranger will approach Buffalo Bill with a bland smile and an outstretched hand. 'Hello, Colonel!' he'll say, 'guess who I am! I'll bet you can't guess who I am!' Cody will give it up. 'Why,' bubbles the stranger, 'don't you remember when you were in Ogden, Utah, in nineteen-two? Remember the crowd at the depot to see you get off the train? Why, I was the man in the white hat!'"

"Just this afternoon," laughed the Major, "Cody came up to where I was standing. He was wiping the sweat from his forehead and his face was red and full of disgust. 'What's the matter?' I inquired. 'Oh,' he answered, 'another one of those d – guessing contests! Why in blazes can't people think up something new?'"

XIII

OUR FRIEND,

THE T. W.

In some localities of this progressive country the pen may still be mightier than the sword; but if, afar from railroad and telegraph, holed away in barbaric seclusion, there really exists a community that writes with a quill and uses elderberry ink and a sandbox, it is safe to say that this community has never been heard of – and the cause is not far to seek. Just possibly, however, it is from such a backwoods township that the busy editor receives those rare manuscripts whose chirography covers both sides of the sheet. In this case the pen is really mightier than the sword as an instrument for cutting the ground out from under the feet of aspiring genius. Just possibly, too, it was from such a place that a typewritten letter was returned to the sender with the indignant scrawl: "You needn't bother to print my letters – I can read writin'."

Nowadays penwork is confined largely to signing letters and other documents and indorsing checks; to use it for anything else should be named a misdemeanor in the statutes with a sliding scale of punishments to fit the gravity of the offense.

It is not to be inferred, of course, that a man will dictate his love letters to a stenographer. Here, indeed, "two's company and three's a crowd." Every man should master the T. W., and when he confides his tender sentiments to paper for the eyes of the One Girl, his own fingers should manipulate the keys and the T. W., should be equipped with a tri-chrome ribbon – red and black record and purple copying. Black will answer for the more subdued expressions, red should be switched on for the warmer terms of endearment, and purple should be used for whatever might be construed as evidence in a court of law. Even billets-doux have been known to develop a commercial value.

When a serviceable typewriter may be bought for $25 what excuse has anyone for side-stepping the inventive ingenuity of the day which makes for clearness and speed? How much does Progress owe the typewriter? Who can measure the debt? How much does civilization owe the telephone, the night-letter, the fast mail and two-cent postage? Even more than to these does Progress owe to that mechanism of springs, keys and type-bars which makes plain and rapid the written thought.

In the Edwards Fiction Factory the T. W., comprises the entire "plant." The "hands" employed for the skilled labor are his own, and fairly proficient. His own, too, is the administrative ability, modest enough in all truth yet able to guide the Factory's destiny with a fair meed of success.

Since the T. W., is so important, Edwards believes in always keeping abreast of improvements. The best is none too good. A typed script, no less than a stereotyped idea, is damned by mediocrity. If a typewriter appears this year which is a distinct advance over last year's machine, Edwards has it. Keeping up-to-date is usually a little expensive, but it pays.

In the early days of his writing Edwards used the old Caligraph. It was a small machine and confined itself to capital letters. Whenever he wished to indicate the proper place for a capital he did it thus: HIS NAME WAS CAESAR, AND HE LIVED IN ROME. If he lost a letter – and letters in those days were not easily replaced – he allowed the unknown quantity "X" to piece out: HIX NAME WAX CAEXAR – . In due time he came to realize the importance of neatness and traded his first Caligraph for a later model equipped with letters from both "cases." During twenty-two years he has purchased at least twenty-five typewriters, each the last word in typewriter construction at the time it was bought. At present he has two machines, one a "shift-key" and the other with every letter and character separately represented on the key-board.

There are many makes of typewriters, and operators are of many minds regarding the "best" makes. Edwards has favored the full key-board as being less of a drain upon the attention than the "shift-key" machine. For the writer who composes upon his machine the operating must become a habit, otherwise an elusive idea may take wings for good while the one who evolved it is searching out the letters necessary to nail it hard and fast to the white sheet. Edwards has recently discovered that he can change from his full key-board to a shift-key and back again without materially interrupting his flow of ideas.

The characters of the key-board used for ordinary business purposes and those in demand by the writer are somewhat different. Not always, on the key-board designed for commercial use, will the exclamation point be found. This, if wanted, must be built up out of a period and a half-ditto mark, – "." plus "'" equals "!" Such makeshifts should be tabooed by the careful writer. Whatever is worth doing at all is worth doing well, and once. Three motions, two at the key-board and one at the back-spacer, are two too many. By all means have the real thing in exclamation points – !

Another makeshift with which Edwards has little patience is the custom of using ditto marks for quotation marks, and semi-dittos for semi-quotes. These, and other characters, may be added to most machines by eliminating the fractions, the oblique mark or the per cent. sign.

It seems poor policy, also, to use a hyphen, or two hyphens, to indicate a dash. Why not have the underscore raised to the position of a hyphen and so have a dash that is a dash?

The asterisk, "*," is a character valuable for indicating footnotes, and the caret is often useful in making typewritten interlineations. All these characters Edwards has on his full key-board machine. On the shift-key machine he must still struggle with the built-up exclamation point, the ditto quotes and the hyphen dash. No wonder he prefers a Smith Premier!

Even the best and most up-to-date typewriter cannot answer all the demands made upon it by writers, however. Some day the growing army of authors will receive due attention in this matter, and the manuscript submitted to editors will compare favorably with the printed story.

In "Habits that Help," a very instructive article by Walter D. Scott, professor of psychology at Northwestern University, published in Everybody's Magazine for September, 1911, appears this paragraph:

"Some time ago I could pick out the letters on a typewriter at a rate of about one per second. Writing is now becoming reduced to a habit, and I can write perhaps three letters a second. When the act has been reduced to the pure habit form, I shall be writing at the rate of not less than five letters per second."

The "pure habit form" is one for those who compose on the typewriter to acquire. It not only means ease of composition, but speed in the performance and perfect legibility.

Until a few years ago, Edwards always carried his typewriter with him on his travels. The machine was large and heavy and had to be handled with care, so its transportation was no easy matter. In course of time, and pending the invention of a practical typewriter to fit the pocket, he became content to leave his machine at home and rent one wherever he happened to be.

During one of his eastern "prospecting" trips, Edwards and his wife left New York for a few summer weeks in the Berkshire Hills. The T. W., remained temporarily in the city to be overhauled and forwarded. For a fortnight Edwards slaved with a pen, writing four manuscripts of 25,000 words each. He appreciated then, as he had never done before, the value of the typewriter in his work. Late in the first week he began writing and telegraphing for his machine to be sent on.

About the hotel it was known that Edwards expected a typewriter by every stage from Great Barrington. He had fretted about the non-arrival of the typewriter, and in some manner had let fall the information that his typewriter weighed sixty pounds. Speculation was rife as to whether the T. W., had blue eyes or gray, and as to what manner of dwarf or living skeleton could fulfill the requirements at sixty pounds. When the machine finally arrived and the square packing case was unloaded, a host of curious ladies received the surprise of their lives.

"Typewriter," commonly used as a generic name for the machine that prints, as well as for the person who operates it, should have its double meaning curtailed. The young lady of pleasing face and amiable deportment, whose deft fingers hover over the keys of a senseless machine, is entitled to something more appropriate in the way of a professional title.

Let it be "typist," after the English fashion; and instead of saying "the typist typewrote the letter," why not say she "typed" it?

An editor once returned a manuscript with a note like this:

Dear Sir: – Put it into narrative form.

Yours truly, "The Editor."

I did so. A week later came this:

"Dear Sir: – A little mystery would help. We like your style very much. Yours truly, "The Editor."

I put in the mystery. A week later, —

"Dear Sir: – You send us good verse. Why not turn the marked paragraphs into verse, with strong influence on story? Well written. "Yours truly, etc."

It was a good idea. The verse was acceptable. It was so acceptable that the editor sent back the story and a check for $5 in payment for the verse – which was all he kept!

XIV

FRESH FIELDS

AND PASTURES NEW

So far in his writing career Harte & Perkins had been the heaviest purchasers of Edwards' fiction. They had given him about all he could do of a certain class of work, and he had not tried to find other markets for the Factory's product. Pinning his hopes to one firm, even though it was the best firm in the business, was unsatisfactory in many respects. For various reasons, any one of which is good and sufficient, a writer should have more than one "string to his bow." Harte & Perkins, jealously watching the tastes of their reading public, were compelled to make many and sudden changes in the material they put out. This directly affected the writers of the material, and Edwards was often left with no prospects at all, and perhaps at just the time when he flattered himself that his prospects were brightest.

In preceding chapters mention has been made of two serial stories in which Edwards had vainly endeavored to interest Harte & Perkins. One of these was "The Man from Dakota," and the other, "He Was A Stranger." These, and another entitled "A Tale of Two Towns," written late in 1900, were ultimately to open new markets.

In a diary for the year 1900, Edwards has this under date of Tuesday, Jan. 2:

"Mr. Paisley called to see me this morning on a business matter. It appears that the proprietor of The Western World had ordered a serial from Opie Read and was not satisfied with it.7 As The Western World goes to press in a few days they must have another story at once. Later in the day I talked with Mr. Underwood the (as I suppose) proprietor, and he asked me to get 'The Man from Dakota' from Mr. Kerr, of The Chicago Ledger. I did so and took the manuscript over to Mr. Paisley. If it is acceptable they are to pay me $200 for it."

Mr. Paisley was a gentleman with whom Mrs. Edwards had become acquainted while attending Frank Holme's School for Illustration, in Chicago. He was a man of much ability.

Under Thursday, Jan. 4, the diary has a memorandum to this effect:

"Mr. Paisley came out to see me at noon. They like 'The Man from Dakota' and will pay me $200 for it, divided into three payments of $50, $50 and $100."

So, finally, "The Man from Dakota" got into print. While it was still appearing in The Western World; Mr. Underwood conceived the idea of booming the circulation of his paper by publishing a mystery story – one of those stories in which the mystery is not revealed until the last chapter, and for the solution of which prizes are offered. He asked Edwards if he would write such a story. Why should Edwards write one when he already had on hand the mystery story unsuccessfully entered in the old Chicago Daily News contest? He offered this to Mr. Underwood. He read it and liked it. Mr. Paisley read it and liked it. What was the very lowest figure Edwards would take for it?

Mr. Underwood, in getting around to this point, told how he had sent for Stanley Waterloo and asked him to write the mystery story. "What will you pay?" inquired Mr. Waterloo. "I'll give you $100," said Mr. Underwood. Whereupon Mr. Waterloo arose in awful majesty and strode from the office. He did not even linger to say good-by.

"Now," said Mr. Underwood to Edwards, with a genial smile, "don't you do that if I offer you seventy-five dollars for 'What Happened to the Colonel.'"

"Cash?" asked Edwards.

"On the nail."

"Give me the money," said Edwards; "I need it."

Now that the diary has been quoted with a reference to Opie Read, perhaps another reference to the same genial and talented gentleman may be pardoned:

Jan. 19, 1900. – "Opie Read made his 'first appearance in vaudeville' this week, and Gertie (Mrs. Edwards) and I went to the Chicago Opera House this afternoon to hear him. He was very good, but I would rather read one of his stories than hear him tell it."

Later in the year Edwards "broke into" the papers served by the McClure Syndicate with "A Tale of Two Towns." After using this serial in metropolitan papers, the McClure people sold it to The Kellogg Newspaper Union to be used in the "patents" sent out to country newspapers. The story was later brought out in cloth by the G. W. Dillingham Co., New York.

The third novel, "He Was A Stranger," had already been refused by Harte & Perkins. Late in May, 1900, Edwards again went "prospecting" to New York. Feeling positive that Harte & Perkins had missed some of the good points in the story, he carried the manuscript with him and once more submitted it. Again it was refused, but Mr. Hall, editor of the "Guest," informed Edwards that he had an excellent story but that it was impossible for Harte & Perkins to consider its purchase. Edwards asked if he knew of a possible market. "Mr. Munsey," was the reply, "is looking for stories for The Argosy, and I'd suggest that you take the story over there and show it to Mr. White, The Argosy's editor." Edwards tucked the novel under his arm and strolled up Fifth Avenue to the offices of the Frank A. Munsey Company. There, and for the first time, he met Mr. Matthew White, Jr.

The impression of power, tremendous ability and a big, two-handed grasp of Argosy affairs which the editor made upon Edwards, at this time, has deepened with the passing years. An author, as well as a keen dramatic critic, Mr. White brings to bear on his editorial duties an intuition that closely approximates genius. He has proved his remarkable fitness for the post he occupies by making The Argosy, since Mr. Munsey "divested it of its knickerbockers," the most widely read of all the purely fiction magazines. And withal he is one of the most pleasant editors whom a writer will ever have the good fortune to meet.

Mr. White was glad to consider "He Was A Stranger." He thumbed over the pages, noted the length, and asked what price Edwards would put upon the manuscript in case it was acceptable. Edwards named $500, and told of "The Brave and Fair" which Harte & Perkins, a few years before, had bought at that figure. Mr. White replied that The Argosy, as yet, was unable to pay such prices, but that he would read the story and, if he liked it, make an offer. A few days later he offered $250 for serial rights. Edwards took into consideration the fact that the story would establish him in the columns of a growing magazine and, with an eye to the future, accepted the offer. He has never had occasion to regret his decision.

From the beginning of the year Edwards had been doing a large amount of five-cent library work for Harte & Perkins. A new weekly had been started, the writer who furnished the copy failed to get his manuscript in on time, and Edwards was given a story to finish and, a few days afterward, the entire series to take care of.

At the time he sold the serial to Mr. White, he was supplying weekly copy for two libraries – the old Five-Cent Library and the new weekly, which shall here be referred to as the Circus Series.

On the proceeds from the sale of "He Was A Stranger" Edwards and his wife had a little outing at Atlantic City. They returned to New York for a few days, and then went on to Boston. Here, comfortably quartered in a hotel, Edwards devoted his mornings to work and his afternoons to seeing the "sights" with Mrs. Edwards. They haunted Old Cambridge, they made pilgrimages to Salem, to Plymouth and to other places, and they enjoyed themselves as they had never done before on an eastern trip. Later they finished out the summer near Monterey, in the Berkshire Hills.

During all these travels the Fiction Factory was regularly grinding out its grist of copy – so many pages a day, so many stories a week. Two libraries, together with a sketch each month for a trade paper published by Harte & Perkins, kept Edwards too busy to prepare any manuscripts for The Argosy. Much of his work, while in the Berkshires, was done in longhand. On this point Mr. Perkins wrote, July 25:

"I should think you would miss your typewriter. I fear that I shall miss it, too, when I read your manuscript, although I find your writing easier to read than that of any of our other writers."

In August the Edwards went West, visited for a time in Michigan and then in Wisconsin, finally returned to the former state and, in the little country town where Edwards was born, bought an old place and settled down.

As with the Golden Star Library, misfortune finally overtook the Circus Series. A telegram was received telling Edwards to hold No. 47 of the Circus Series pending instructions by letter. The letter instructed him to close up finally the adventures of the hero and his friends and bring their various activities to an appropriate end. The series was continued, for a while longer, with a brand-new hero in each story; but Edwards was requested to write but three of the stories in the new form.