полная версия

полная версияThe Fiction Factory

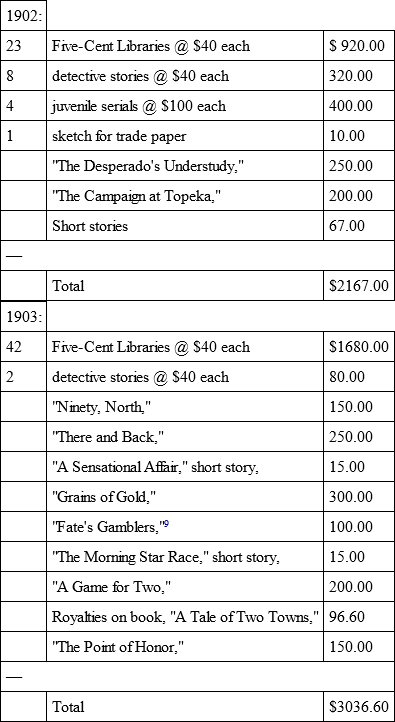

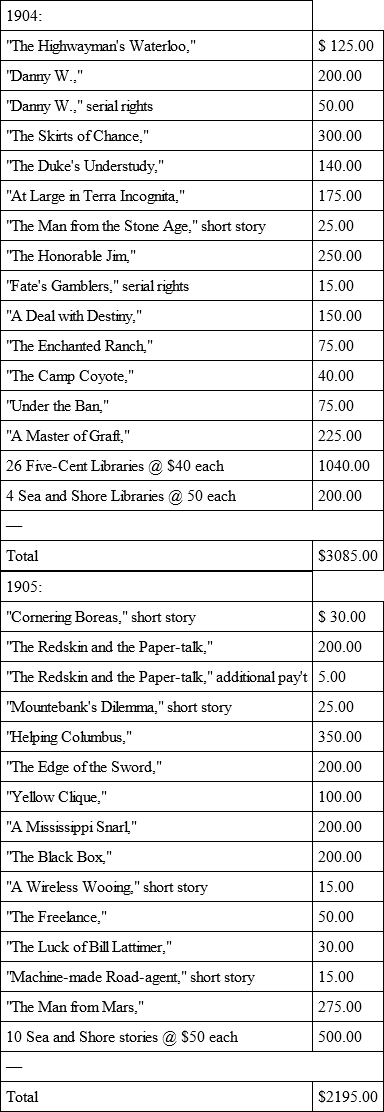

The two years' work figured out in this wise:

Примечание 19

As several gentlemen in these times, by the wonderful force of genius only, without the least assistance of learning, perhaps without being able to read, have made a considerable figure in the republic of letters; the modern critics, I am told, have lately begun to assert, that all kind of learning is entirely useless to a writer, and indeed, no other than a kind of fetters on the natural sprightliness and activity of the imagination, which is thus weighed down, and prevented from soaring to those high flights which otherwise it would be able to reach.

This doctrine, I am afraid, is at present carried much too far; for why should writing differ so much from other arts? The nimbleness of a dancing-master is not at all prejudiced by being taught to move; nor doth any mechanic, I believe, excercise his tools the worse by having learnt to use them. —Fielding, "Tom Jones."

XVII

ETHICS OF THE

NICKEL NOVEL

Is the nickel novel easy to write? The writer who has never attempted one is quite apt to think that it is. There are hundreds of writers, the Would-be-Goods, making less than a thousand a year, who would throw up their hands in horror at the very thought of debasing their art by contriving at "sensational" five-cent fiction. So far from "debasing their art," as a matter of fact they could not lift it to the high plane of the nickel novel if they tried. Of these Would-be-Goods more anon – to use an expression of the ante-bellum romancers. Suffice to state, in this place, writers of recognized standing, and even ministers, have written – and some now are writing – these quick-moving stories. There's a knack about it, and the knack is not easy to acquire. No less a person than Mr. Richard Duffy, formerly editor of Ainslee's and later of the Cavalier, a man of rare gifts as a writer, once told Edwards that the nickel novel was beyond his powers.

So far as Edwards is concerned, he gave the best that was in him to the half-dime "dreadfuls," and he made nothing dreadful of them after all. He has written hundreds, and there is not a line in any one of them which he would not gladly have his own son read. In fact, his ethical standard, to which every story must measure up, was expressed in this mental question as he worked: "If I had a boy would I willingly put this before him?" If the answer was No, the incident, the paragraph, the sentence or the word was eliminated. In 1910 Edwards wrote his last nickel novel, turning his back deliberately on three thousand dollars a year (they were paying him $60 each for them then), not because they were "debasing his art" but because he could make more money at other writing – for when one is forty-four he must get on as fast as he can.

The libraries, as they were written by Edwards, were typed on paper 8-1/2" by 13", the marginal stops so placed that a typewritten line approximated the same line when printed. Eighty of these sheets completed a story, and five pages were regularly allowed to each chapter. Thus there were always sixteen chapters in every story.

First it is necessary to submit titles, and scenes for illustration. Selecting an appropriate title is an art in itself. Alliteration is all right, if used sparingly, and novel effects that do not defy the canons of good taste should be sought after. The title, too, should go hand in hand with the picture that illustrates the story. This picture, by the way, has demands of its own. In the better class of nickel novels firearms and other deadly weapons are tabooed. The picture must be unusual and it must be exciting, but its suggested morality must be high.

The ideas for illustrations all go to the artist days or even weeks in advance of the stories themselves. It is the writer's business to lay out this prospective work intelligently, so that he may weave around it a group of logical stories.

Usually the novels are written in sets of three; that is, throughout such a series the same principal characters are used, and three different groups of incidents are covered. In this way, while each story is complete in itself, it is possible to combine the series and preserve the effect of a single story from beginning to end. These sets are so combined, as a matter of fact, and sold for ten cents.

Each chapter closes with a "curtain." In other words, the chapter works the action up to an interesting point, similar to a serial "leave-off," and drops a quick curtain. Skill is important here. The publishers of this class of fiction will not endure inconsistency for a moment. The stories appeal to a clientele keen to detect the improbable and to treat it with contempt.

Good, snappy dialogue is favored, but it must be dialogue that moves the story along. An apt retort has no excuse in the yarn unless it really belongs there. A multitude of incidents – none of them hackneyed – is a prime requisite. Complexity of plot invites censure – and usually secures it. The plot must be simple, but it must be striking.

One author failed because he had his hero-detective strain his massive intellect through 20,000 words merely to recover $100 that had been purloined from an old lady's handbag. If the author had made it a million dollars stolen from a lady like Mrs. Hetty Green, probably his labor would have been crowned with success. These five-cent heroes are in no sense small potatoes. They may court perils galore and rub elbows with death, now and then, for nothing at all, but certainly never for the mere bagatelle of $100.

The hero does not drink. He does not swear. Very often he will not smoke. He is a chivalrous gentleman, ever a friend of the weak and deserving. He accomplishes all this with a ready good nature that has nothing of the goody-good in its make-up. The hero does not smoke because, being an athlete, he must keep in constant training in order to master his many difficulties. For the same reason he will not drink. As for swearing, it is a useless pastime and very common; besides, it betrays excitement, and the hero is never excited.

The old-style yellow-back hero was given to massacres. He slew his enemies valiantly by brigades. Not so the modern hero of the five-cent novel. Rarely, in the stories, does any one cross the divide. And whenever the villain is hurt, he is quite apt to recover, thank the hero for hurting him – and become his sworn friend.

The story must be clean, and while it must necessarily be exciting, it must yet leave the reader's mind with a net profit in all the manly virtues. Is this easy?

Please note this extract from a letter written by Harte & Perkins Dec. 25, 1902 – it covers a point whose humor, Edwards thought, drew the sting of dishonesty:

"Your last story, No. 285, opened well, had plenty of good incidents and was interesting, but there are several points in which it might have been improved.

Your description of Two Spot's scheme of posing Dutchy as a petrified boy is amusing, but the plan was dishonest and a piece of trickery. It was all right, perhaps, to let the boys go ahead without the knowledge of the Hero, but when he learned of it he should have put a stop to the plan immediately. It was all right to have him laugh at it, but at the same time he should have spoken severely to the boys about it and ordered them to return the money they had received through their trick. He did not do this in your story and it was necessary for me to alter it considerably in the first part on that account.

The Hero is supposed to be the soul of honor, and in your story he is posed as a party to a deception practised on the citizens of Ouray, by which they were defrauded of the money they paid for admission to see the supposed "petrified boy." Such conduct on his part would soon lose for him the admiration of the readers of the weekly, as it places him on a moral level, almost, with the robbers whom he is bringing to justice."

Consider that, you Would-be-Goods, who are not above putting worse things in your "high-class" work. And can you say "I am holier than thou" to the conscientious writer who turns out his 20,000 or 25,000 words a week along these ethical lines? Handsome is as handsome does!

Somebody is going to write these stories. There is a demand for them. The writer who can set hand to such fiction, who meets his moral responsibilities unflinchingly, is doing a splendid work for Young America.

And yet, as stated in a previous chapter, there are nickel novels and nickel novels – some to read and some to put in the stove unread. High-minded publishers, however, are not furnishing the careful head of the family with material for his kitchen fire.

It costs you nothing to think, but it costs infinitely to write. I therefore preach to you eternally that art of writing which Boileau has so well known and so well taught, that respect for the language, that connection and sequence of ideas, that air of ease with which he conducts his readers, that naturalness which is the true fruit of art, and that appearance of facility which is due to toil alone. A word out of place spoils the most beautiful thought. —Voltaire to Helvetius, a young author.

XVIII

KEEPING

EVERLASTINGLY AT IT

Edwards had not visited New York in 1903, but he landed there on Friday, Jan. 1, 1904, – literally storming in on a train that was seven hours late on account of the weather. A cab hurried him and his wife to the place in Forty-fourth street where the pleasant landlady used to hold forth, but they found, alas! that the old stamping ground was in the hands of strangers. It was like being turned away from home.

Where should they go? Edwards remembered that, on one of his previous visits to New York, Mr. Perkins had recommended the St. George Hotel, over in Brooklyn. The St. George was within a few blocks of the south end of the bridge and the offices of Harte & Perkins were in William street, close to the north end. So Edwards and his wife went to the Brooklyn hotel and there established their headquarters.

On Jan. 2 Edwards called on the patrons of his Factory. The result was not particularly encouraging. Harte & Perkins instructed him to stop work on the Five-Cent Library, but said that in about two months they would have a new library for him to take care of.

Edwards had brought with him to the city his dramatic version of "The Tangle in Butte," the play which had come so near turning $5,000 into the Factory's strong-box. It was Edwards' hope that he might be able to dispose of the play, but the hope went glimmering when he learned that there were 10,000 actors stranded in New York, and that things theatrical were generally in a bad way.

During 1903 Edwards had corresponded with Mr. H. H. Lewis, editor of The Popular Magazine, a recent venture of Messrs. Street & Smith's. He had submitted manuscripts to Mr. Lewis but they had not proved to be in line with The Popular's requirements. It is difficult, through correspondence, to discover just what an editor wants. The only way to get at such a thing properly is by personal interview. If the would-be contributor does not then get the editor's needs clearly in mind it is his own fault.

Edwards called on Mr. Lewis and had a pleasant chat with him. The assistant editor was Mr. A. D. Hall, a capable gentleman who had been with Messrs. Street & Smith for many years, and with whom Edwards was well acquainted.

At that time Louis Joseph Vance was writing for The Popular Magazine, among others, and Edwards met him in Mr. Lewis' office. As Edwards was leaving, after outlining a novelette and receiving a commission to write it, he paused with one hand on the door-knob.

"I'll turn in the story, Mr. Lewis," said he, "and I hope you'll like it and buy it."

"Of course he'll like it and buy it," called out Vance. "You're going to write it for him, aren't you?"

"Why, yes," returned Edwards, "but – "

"You're not a peddler," interrupted Vance, "to write stuff and go hawking it about from office to office. We're writers, and when we know what a man wants we deliver the goods."

This was before the days of "The Brass Bowl" and "Terence O'Rourke," but already Vance had found himself and was striking the key-note of confidence. Confidence– that's the word. Back it up with fair ability and the writer will go far.

From The Popular's editorial rooms Edwards went up Fifth avenue for a call on the editor of The Argosy. Much to his disappointment Mr. White was out of town for New Year's and would not return until the following week.

The story which Edwards had presented to Mr. Lewis in its oral and tabloid form was one that had been written in 1903 and turned down by Mr. White. Before offering the manuscript to The Popular, Edwards intended to rewrite it and strengthen it.

A typewriter was ordered sent over to the St. George Hotel, and on Jan. 3 the rewriting of the novelette was begun. The story was called "The Highwayman's Waterloo," or something to that effect. On the following day twenty-four pages of the manuscript were submitted to Mr. Lewis, won his approval, and the rewriting proceeded.

Two chapters of a serial were also offered to Mr. White for examination. The story was called "The Skirts of Chance," and had been begun before Edwards left home.

During 1902 and '03 Edwards had worked, at odd times, on what he designed to be a "high-class" juvenile story. It was 60,000 words in length, when completed in the Summer of 1903, and in September he had submitted it to Dodd, Mead & Company. Not having heard from the story, on this January day that saw him passing out fragments of manuscripts to The Popular and The Argosy he went on farther up Fifth avenue and dropped in to ask D., M. & Co., how "Danny W.," was fareing at the hands of their readers. He was told that five readers had examined the story and that it was then in the hands of the sixth! Some of the readers – and this came to him privately – had turned in a favorable report. Because of this, the author of "Danny W.," went back to Brooklyn considerably elated. It would be an honor indeed to have the book break through such a formidable brigade of readers and get into the catalogue of the good old house of Dodd, Mead & Company.

The "highwayman" novelette was finished and submitted in its complete form on Jan. 6. On the same day Mr. White informed Edwards that he was well pleased with the two chapters of "The Skirts of Chance" and told him to proceed with it.

Fortune was on the upward trend for Edwards, and he was sent for by Dodd, Mead & Company, on Jan. 15, and informed that they would either bring out "Danny W.," on a royalty or pay a cash price for the book rights. Edwards, remembering his disastrous publishing experience with "A Tale of Two Towns," accepted $200 in cash.

Mr. Lewis bought the novelette for $125, and Harte & Perkins, on the same day, gave Edwards a new library to do – 35,000 words in each story at $50.

Complete manuscript of "The Skirts of Chance" was submitted to Mr. White on Jan. 22, and on Jan. 27 Edwards received $300 for it.

By Feb. 8 Edwards had written and sold to Mr. Lewis another novelette entitled, "The Duke's Understudy," for which he received $140.

On Feb. 9 he and his wife returned to Michigan. Edwards had been in New York forty days and had gathered in $965. He left New York with orders for Argosy serials and with the new library, "Sea and Shore," to be turned in at the rate of one story every two months.

In May he was requested to go on with the Old Five-Cent Library. These stories were forwarded regularly one each week, until November, when orders were again discontinued.

In September, "Danny W.," appeared. As with "A Tale of Two Towns," the reviewers were more than kind to "Danny W.," and there is just a possibility that they killed him with kindness. The idea obtains, in supposedly well-informed circles, that the only way for reviewers to help a book is to damn it utterly. Be this as it may, although illustrated in color and put out in the best style of the book-maker's art, "Danny W.," did not prove much of a success. A California paper bought serial rights on the story for $50, and thus the book netted the author, all told, the modest sum of $250.

During this year, also, The A. N. Kellogg Newspaper Company sold serial rights on "Fate's Gamblers" for $30, took 50 per cent. as a commission and presented Edwards with what was left.

A short story, "The Camp Coyote," was sold to Mr. Titherington, for Munsey's; and Edwards had opened a new market in Street & Smith's magazines. Thus was brought to a close a fairly prosperous year.

In 1905 the returns slid backward a little. During this year, and the year preceding, some stories which had failed with Mr. White were received with favor by Mr. Kerr, of The Chicago Ledger– at the Ledger price, ranging from $30 upward to $75.

The Woman's Home Companion, to which Edwards had vainly tried to sell serial rights on "Danny W.," accepted a two-part story entitled, "The Redskin and the Paper-Talk," and paid $200 for it. This is the story of which a chapter was lost in the composing room, and Edwards received an honorarium of $5 for having a carbon duplicate of the few missing pages.

In 1905, also, The American Press Association did business with Edwards to the amount of $30. Another market for the Edwards' product – worth mentioning even though the amount of business done was not large.

The returns for the two years were as follows:

Good, philosophical Ras Wilson once said to a new reporter, "Young man, write as you feel, but try to feel right. Be good humored toward every one and everything. Believe that other folks are just as good as you are, for they are. Give 'em your best and bear in mind that God has sent them, in his wisdom, all the trouble they need, and it is for you to scatter gladness and decent, helpful things as you go. Don't be particular about how the stuff will look in print, but let'er go. Some one will understand. That is better than to write so dash bing high, or so tarnashun deep, that no one understands. Let'er go."

There was once a poor man hounded to death by creditors. Ruin and suicide vied for his surrender. But he was a man of the twentieth century, and flippantly but with unbounded faith he collected a few odd pennies and hied him to a newspaper office. Stopping scarcely to frame his sentence he inserted a "want" advertisement, stating his circumstances and declaring he would commit suicide unless aid was proffered. Within twenty-four hours he had $250; before another sun his employer advanced as much more. Carefully advising the newspaper to discontinue the advertisement, he paid off his creditors – and lived happily ever afterward! No, this is not a fairy tale. The time was a few weeks ago, the city Chicago and the newspaper, The Tribune. The moral is, that originality in writing, coupled with a fresh idea, brings a check.

XIX

LOVE YOUR WORK

FOR THE

WORK'S SAKE

The sentiment which Edwards has tried to carry through every paragraph and line of this book is this, that "Writing is its own reward." His meaning is, that to the writer the joy of the work is something infinitely higher, finer and more satisfying than its pecuniary value to the editor who buys it. Material success, of course, is a necessity, unless – happy condition! – the writer has a private income on which to draw for meeting the sordid demands of life. But this also is true: A writer even of modest talent will have material success in a direct ratio with the joy he finds in his work! – Because, brother of the pen, when one takes pleasure in an effort, then that effort attracts merit inevitably. If any writing is a merciless grind the result will show it – and the editor will see it, and reject.

There are times, however, when doubt shakes the firmest confidence. A writer will have moods into which will creep a distrust of the work upon which he is at that moment engaged. If necessity spurs him on and he cannot rise above his misgivings, the story will testify to the lack of faith, doubts will increase as defects multiply and the story will be ruined. THE WRITER MUST HAVE FAITH IN HIS WORK QUITE APART FROM THE MONEY HE EXPECTS TO RECEIVE FOR IT. If he has this faith he reaches toward a spiritual success beside which the highest material success is paltry indeed.

When a writer sits down to a story let him blind his eyes to the financial returns, even though they may be sorely needed. Let him forget that his wares are to be offered for sale, and consider them as being wrought for his own diversion. Let him say to himself, "I shall make this the best story I have ever written; I shall weave my soul into its warp and whether it sells or not I shall be satisfied to know that I have put upon paper the BEST that is in me." If he will do this, he will achieve a spiritual success and – as surely as day follows night – a material success beyond his fondest dreams. BUT he must keep his eye single to the TRUE success and must have no commerce in thought with what may come to him materially.

To some, all this may appear too idealistic, too transcendental. There are natures so worldly, perhaps even among writers, as to scoff at the idea of spiritual success. They are overshadowed by the Material, and when the Spiritual, which is the true source of their power, is no longer the "still, small voice" of their inspiration, they will be bankrupt materially as well.

A writer cannot hide himself in his work. His individuality is written into it, and he may be read between the lines for what he is. A creation reflects the creator, and that the work may be good the writer should have spiritual ideals and do his utmost to live up to them. Let him have a purpose, be it never so humble, to benefit in some way his fellow-man, and let him hew steadily to the line. Love your work for the work's sake and material benefits "will be added unto you."

Years ago Edwards found an article in a newspaper that appealed to him powerfully. He clipped it out, preserved it and has made it of great help in his writing. It is a wonderful "Doubt-destroyer." In the hope that it may be an inspiration to others, he reproduces it here:

STANDARDS OF SUCCESSAt a time when material success is so generally regarded as the chief goal of human effort it is interesting to find a man in Professor Hadley's position presenting arguments for a broader view of the question. In his baccalaureate sermon the president of Yale offered the graduates some advice which at least they should find stimulating. He does not discredit or discourage the ambition for practical success but he makes it plain that in his view there is danger in measuring success in life "by the concrete results with which men can credit themselves." "We should value life," he declares, "as a field of action." We should care for the doing of things quite as much as for the results. Tried by this standard, aspiration and effort are to be more highly prized than achievement itself. The man who sincerely strives for a great object has succeeded, whether or not the object is attained or its attainment brings any tangible reward.

It is no novelty, of course, to hear a college president upholding ideal standards and rejecting utilitarian views of success, but few of the educators have cared to follow their theories, as President Hadley does, to their logical conclusion. Probably a majority of them would applaud Nansen's courage in attempting to reach the north pole but would question the utility of the attempt. President Hadley admires Nansen simply "because he succeeded in getting so much nearer the pole than anybody before him ever did," and thinks it is one of the most discouraging testimonies to the false standards of the nineteenth century that Nansen feels compelled to justify himself on the basis of the scientific results of his expedition. Furthermore, a man who tries to get to the pole is engaged in a glorious play, "which justifies more risk and more expenditure of life than would be warranted for a few miserable entomological specimens, however remote from the place where they had previously been found."