полная версия

полная версияThe Fiction Factory

The young man of to-day has no lack of exhortations to lead the life of strenuous effort. It is as well that he should be taught also that the reward for this effort will be barren if the whole object sought be material benefit to himself. Life is something to be used. Whether or not it has been successfully used depends not on the results so much as on the object sought and the earnestness of the seeking. It is somewhat novel to find an American college president expounding this philosophy to his students, but the philosophy is, on the whole, helpful. It will spur to effort in crises where the desire for more material success fails to provide a sufficient incentive.

A certain New York author is fond of his own work, and Robert W. Chambers is responsible for the story that he called at one of the libraries to find out how his latest book was going. He hoped to have his vanity tickled a little.

"Is – in?" he said to the librarian, naming his book.

"It never was out," was the reply.

What is a great love of books? It is something like a personal introduction to the great and good men of all past times. Books, it is true, are silent as you see them on your shelves; but, silent as they are, when I enter a library I feel almost as if the dead were present, and I know if I put questions to these books they will answer me with all the faithfulness and fullness which has been left in them by the great men who have left the books with us. —John Bright.

The spring poet has been much exploited in the comic papers. The would-be novelist has been plastered with signs and tokens until one could not fail to recognize him in the dark. But the ordinary, commonplace, experienced writer has been so shamefully neglected that few realize his virtues. The editor recognizes his manuscript as far off as he can see it, and seizes upon it with joy. The manuscript is typewritten and punctuated. It bears the author's name and address at the top of the first page. It is signed with the author's name at the end. It is NOT tied with a blue ribbon. No, the blue ribbon habit is not a myth. It really exists in every form from pale baby to navy No. 4 and in every shape from a hard knot to an elaborate rosette —Munsey's.

XX

THE LENGTHENING

LIST OF PATRONS

During the year 1906 the patrons of the Fiction Factory steadily increased in number. The Blue Book, The Red Book, The Railroad Man's, The All-Story, The People's– all these magazines bought of the Factory's products, some of them very liberally. The old patrons, also, were retained, Harte & Perkins taking a supply of nickel novels and a Stella Edwards' serial for The Guest.

Edwards' introduction to The Blue Book came so late in the year that the business falls properly within the affairs of 1907. The first step, however, was taken on Aug. 13, 1906, and was in the form of the following letter:

"My dear Mr. Edwards:

Why don't you send me, with a view to publication in The Blue Book, as we have renamed our old Monthly Story Magazine, one or more of those weird and fantastic novelettes of yours? If you have anything ready, let me see it. I can at least assure you of a prompt decision and equally prompt payment if the story goes. Anything you may have up to 6,000 words I shall be very glad to see for The Red Book.

Yours very truly,"Karl Edwin Harriman."Here was a pleasant surprise for Edwards. He had met Mr. Harriman the year before in Battle Creek, Michigan. At that time Mr. Harriman was busily engaged hiding his talents under a bushel known as The Pilgrim Magazine. When the Red Book Corporation of Chicago, kicked the basket to one side, grabbed Mr. Harriman out from under it and made off with him, the aspect of the heavens promised great things for literature in the Middle West. And this promise, by the way, is being splendidly fulfilled.

When you take down your "Who's Who" to look up some personage sufficiently notorious to have a place between its red covers, if you find at the end of his name the words, "editor, author," you may be sure that there is no cloud on the title that gives him a place in the book. You will know at once that he must have been a good author or he would never have been promoted from the ranks; and having been a good author he is certainly a better editor than if the case were otherwise, for he knows both ends of the publishing trade.

Having been through the mill himself, Mr Harriman has a fellow-feeling for his contributors. He knows what it is to take a lay figure for a plot, clothe it in suitable language, cap it with a climax and put it on exhibition with a card: "Here's a Peach! Grab me quick for $9.99." Harriman's "peaches" never came back. The author of "Ann Arbor Tales," "The Girl and the Deal," and others has been successful right from the start.

No request for material received at the Edwards' Factory ever fails of a prompt and hearty response. A short story and a novelette were at once put on the stocks. They were constructed slowly, for Edwards could give them attention only during odd moments taken from his regular work. The short story was finished and submitted long in advance of the novelette. This letter, dated Sept. 18, will show its success:

"My Dear Old Man: Why don't you run on here and see me, now and again. Oh, yes, New York's a lot better, but we're doing things here, too. About 'Cast Away by Contract,' it's very funny – such a ridiculously absurd idea that it's quite irresistible. How will $75 be for it? O. K.? It's really all I can afford to pay for a story of its sort, and I do want you in the book. Let me hear as soon as possible and I will give it out to the artist.

Very truly yours,"K. H."And so began the business with Mr. Harriman. He still, at this writing (1911), has a running account on the Factory's books and is held in highest esteem by the proprietor.

A letter, written May 13, 1905, (a year dealt with in a previous chapter), is reproduced here as having a weighty bearing on the events of 1906. It was Edwards' first letter from a gentleman who had recently allied himself with the Munsey publications. As a publisher Mr. F. A. Munsey is conceded to be a star of the first magnitude, but this genius is manifest in nothing so much as in his ability to surround himself with men capable of pushing his ideas to their highest achievement. Such a man had been added to his editorial staff in the person of Mr. R. H. Davis. Mr. Davis, like Mr. Bryan, hails originally from Nebraska. Although he differs somewhat from Mr. Bryan in political views, he has the same powers as a spellbinder. He's Western, all through, is "Bob" Davis, bluff, hearty and equally endowed with stories, snap and sincerity.

"Dear Sir:

We would like to have a few pictures of those writers who have contributed considerably to our various magazines. It is obvious that this refers to you. Therefore, if you will send us a portrait it will be greatly appreciated.

Very truly yours,"R. H. Davis."Mr. Davis got the picture; also a serial or two and some short stories for new publications issued by the Munsey Company of which he was editor. Late in 1905 he called for a railroad serial, and he wanted a particularly good one.

Edwards had never tried his hand at such a story. He knew, in a general way, that the "pilot" was on the front end of a locomotive, and that the "tender" was somewhere in the rear, but his technical knowledge was hazy and unreliable. The story, if accepted, was to appear in The Railroad Man's Magazine, would be read by "railroaders" the country over, and would be damned and laughed at if it contained any technical "breaks."

Here was just the sort of a nut Edwards liked to crack. The perils of the undertaking lent it a zest, and were a distinct aid to industry and inspiration. He resolved that he would give Mr. Davis a story that would bear the closest scrutiny of railroad men and win their interest and applause. To this end he studied railroads, up and down and across. He absorbed what he could from books, and the rest he secured through personal investigation. When the story was done, he submitted the manuscript to a veteran of the rails – one who had been both a telegraph operator and engineer – and this gentleman had not a change to suggest! Mr. Davis took the story aboard. While it was running in the magazine a reader wrote in to declare that it must have been written by an old hand at the railroad game: the author of the letter had been railroading for thirty-five years himself, and felt positive that he ought to know! "The Red Light at Rawlines" scored a triumph, proving the value of study, and the ability to adjust one's self to an untried situation.

Edwards had imbibed too much technical knowledge to exhaust it all on one story, so he wrote another and sent it to Mr. White. The latter informed him:

"I turned 'Special One-Five-Three' over to The Railroad Man's Magazine at once, without reading it, and they are sending you a check for it this week, I understand. This does not mean that I did not care to consider it for The Argosy. I certainly have an opening for more of your stories, but when you took the railroad for your theme and treated it so intelligently, I think it better that you give The Argosy some other subject matter."

Another story, written this year to order, also serves to show that facility in handling strange themes or environments does not always depend upon personal acquaintance with the subject in hand. Intelligent study and investigation can many times, if not always, piece out a lack of personal experience. Blazing a course through terra incognita in such a manner, however, is not without its dangers.

Harte & Perkins wished to begin the yearly volume of The Guest with a Stella Edwards serial. This story was to have, for its background, the San Francisco earthquake. Nearly the whole action of the yarn was to take place in the city itself. Edwards had never been there. He had vague ideas regarding the "Golden Gate," Oakland and other places, but for accurate knowledge he was as much at sea as in the case of the railroad story. He set the wheels of industry to revolving, however, and familiarized himself so thoroughly with the city from books, newspapers and magazines that the editor of The Guest, an old San Francisco newspaper man, had this to say about the story:

"It will please you to learn that we think 'A Romance of the Earthquake' a very interesting story, with plenty of brisk action, picturesque in description, and DISPLAYING A THOROUGH KNOWLEDGE OF CALIFORNIA'S METROPOLIS AND VICINITY."

Although these are interesting problems to solve, yet Edwards, as a rule, prefers dealing with material that has formed a part of his own personal experiences.

His "prospecting" trip for the year brought him into New York on Monday, Nov. 12. On Tuesday (his "lucky day," according to the Coney Island seer of fateful memory), he called on Mr. White, and Mr. White took him across the hall and introduced him to Mr. Davis. The latter gentleman ordered four serials and, for stories of a certain length, agreed to pay $500 each.

Next day Edwards dropped in at the offices of Street & Smith and submitted a novelette – "The Billionaire's Dilemma" – to Mr. MacLean, editor of The Popular Magazine (Mr. Lewis having retired from that publication some time before). Mr. MacLean carried the manuscript in to Mr. Vivian M. Moses, editor of People's and the latter bought it. This story made a hit in the People's and won from Mr. George C. Smith, of the firm, a personal letter of commendation. Result: More work for The People's Magazine.

About the middle of December, Edwards and his wife left for their home in Michigan. They had been in the city a month, and during that time Edwards had received $1150 for his Factory's products. The year, financially, was the best Edwards had so far experienced; but it was to be outdone by the year that followed.

During 1907 a great deal of writing was done for Mr. Davis. Among other stories submitted to him was one which Edwards called, "On the Stroke of Four." Regarding it Mr. Davis had expressed himself, May 6, in characteristic vein:

"My dear Colonel:

Send it along. The title is not a bad one. I suppose it will arrive at a quarter past five, as you are generally late…

Now that spring is here, go out and chop a few kindlings against the canning of the fruit. This season we are going to preserve every dam thing on the farm. In the meantime, put up a few bartletts for little Willie. We may drop in provided the nest contains room."

He received an urgent invitation to "drop in." But he didn't. He backed out. Possibly he was afraid he would have to "pioneer it" in the country, after years of metropolitan luxury in the effete East. Or perhaps he was afraid that Edwards might read some manuscripts to him. Whatever the cause, he never appeared to claim the "bartletts," made ready for him with so much painstaking care by Mrs. Edwards. But this was not the only count in the indictment. He sent back "On the Stroke of Four!" And this was his message:

"Up to page 106 this story is a peach. After that it is a peach, but a rotten peach, and I'd be glad to have you fix it up and return it."

After Edwards has finished a story he has an ingrained dislike for tampering with it any further. However, had he not been head over ears in other work, he would probably have "fixed up" the manuscript for Mr. Davis. In the circumstances, he decided to try its fortunes elsewhere. Mr. Moses took it in, paid $400 for it, and pronounced it better than "The Billionaire's Dilemma."

At a later date, Mr. Davis wanted another sea story for Ocean which, at that time, was surging considerably. "On the Stroke of Four" had been designed to fill such an order. Inasmuch as it had failed, Edwards wrote a second yarn which was accepted at $450.

The sea, and the people who go down to it in ships, to say nothing of the ships themselves, were all out of Edwards' usual line. He prepared himself by reading every sea story he could lay hands on, long or short. He bought text-books on seamanship and navigation, and whenever there were manoeuvers connected with "working ship" in a story, Edwards puzzled them out with the help of the text-books. With both deep-water serials he succeeded tolerably well. He is sure, at least, that he didn't get the spanker-boom on the foremast, nor the jib too far aft.

Harte & Perkins again favored the Factory with an order for a "Stella Edwards" to begin another volume of The Guest. This was an automobile story, "The Hero of the Car," and was accepted and highly praised.

Another novelette, "An Aerial Romance," was bought by Mr. Moses for The People's Magazine.

Beginning in March, Edwards had written some more nickel novels for Harte & Perkins – not the old Five-Cent Weekly, for that he was never to do again – but various stories, in odd lots, to help out with a particular series. On July 14 he was switched to another line of half-dime fiction, and this work he kept throughout the remainder of the year.

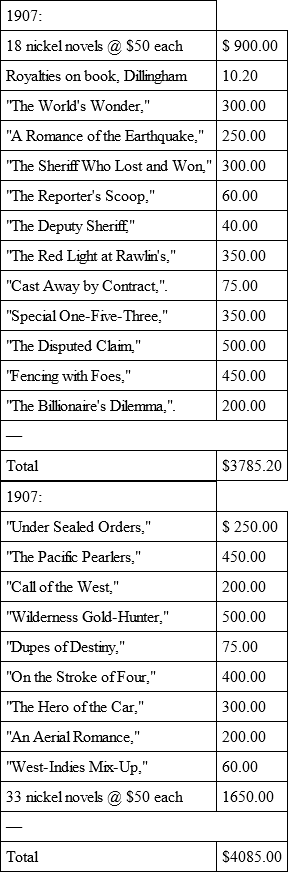

For the two years the Factory's showing stands as follows:

In that remarkable group of authors who made the dime novel famous, the late Col. Prentiss Ingraham was one of the giants. These "ready writers" thought nothing of turning out a thousand words of original matter in an hour, in the days when the click of the typewriter was unknown, and of keeping it up until a novel of 70,000 words was easily finished in a week. But to Col. Ingraham belongs the unique distinction of having composed and written out a complete story of 35,000 words with a fountain pen, between breakfast and breakfast. His equipment as a writer of stories for boys was most varied and valuable, garnered from his experience as an officer in the Confederate army, his service both on shore and sea in the Cuban war for independence, and in travels in Mexico, Austria, Greece and Africa. But he is best known and will be most loyally remembered for his Buffalo Bill tales, the number of which he himself scarcely knew, and which possessed peculiar value from his intimate personal friendship with Col. Cody.

XXI

A WRITER'S

READING

That old Egyptian who put above the door of his library these words, "Books are the Medicines of the Soul," was wise indeed. But the Wise, ever since books have been made, have harped on the advantage of good literature, and have said all there is to be said on the subject a thousand times over. If one has any doubts on this point let him consult a dictionary of quotations. No intelligent person disputes the value of books; and it should be self-evident that no writer, whose business is the making of books, will do so. To the writer books are not only "medicines for the soul" but tonics for his technique, febrifuges for his rhetorical fevers and prophylactics for the thousand and one ills that beset his calling. A wide course of general reading – the wider the better – is part of the fictionist's necessary equipment; and of even more importance is a specializing along the lines of his craft.

"Omniverous reader" is an overworked term, but it is perfect in its application to Edwards. From his youth up he has devoured everything in the way of books he could lay his hands on. The volumes came hap-hazard, and the reading has been desultory and, for the most part, without system. If engaged on a railroad story, he reads railroad stories; if a tale of the sea claims his attention, then his pabulum consists of sea-facts and fiction, and so on. The latest novel is a passion with him, and he would rather read a story by Jack London, or Rex Beach, or W. J. Locke than eat or sleep – or write something more humble although his very own. He is fond of history, too, and among the essayists he loves his Emerson. Nothing so puts his modest talents in a glow as to bring them near the beacon lights of Genius.

Edwards has a library of goodly proportions, but it is a hodge-podge of everything under the sun. Thomas Carlyle "keeps company" with Mary Johnston on his bookshelves, Marcus Aurelius rubs elbows with Frank Spearman, "France in the Nineteenth Century" nestles close to "The Mystery" from the firm of White & Adams, and four volumes of Thackeray are cheek by jowl with Harland's "The Cardinal's Snuff-Box." A most reprehensible method of book keeping, of course, but to Edwards it is a delightful confusion. To him the method is reprehensible only when he wants a certain book and has to spend half a day looking for it. Some time, some blessed time – he has promised himself for years and years, – he will catalogue his books just as he has catalogued his clippings.

Books that concern themselves with the writer's trade are many, so many that they may be termed literally an embarrassment of riches. If a writer had them all he would have more than he needed or could use. Books on the short story by J. Berg Eisenwein and James Knapp Reeve, Edwards considers indispensable. They are to be read many times and thoroughly mastered. "Roget's Thesaurus" is a work which Edwards consulted until it was dogeared and coverless; he then presented it to an impecunious friend with a well-defined case of writeritis and has since contented himself with the large "Thesaurus Dictionary of the English Language," by F. A. March, LL. D. This flanks him on the left, as he sits at his typewriter, while Webster's "Unabridged" closes him in on the right. The Standard Dictionary is also within reach. Dozens and dozens of books about writers and writing have been read and are now gathering dust. After a writer has once charged himself to the brim with "technique," he should cease to bother about it. If he has read to some purpose his work will be as near technical perfection as is necessary, for unconsciously he will follow the canons of the art; while if he loads and fires these "canons" too often, they will be quite apt to burst and blow him into that innocuous desuetude best described as "mechanical." He should exercise all the freedom possible within legitimate bounds, and so acquire individuality and "style" – whatever that is.

No sane man in any line of trade or manufacturing will attempt to do business without subscribing to one or more papers or magazines covering his particular field. He wants the newest labor-saving wrinkle, the latest discoveries, tips on new markets, facts as to what others in the same business are doing, and countless other fresh and pertinent items which a good trade paper will furnish. A writer is such a man, and he needs tabulated facts as much as any other tradesman or manufacturer. Periodicals dealing with the trade of authorship are few, but they are helpful to a degree which it is difficult to estimate.

From the beginning of his work Edwards has made it a point to acquire every publication that dealt with the business of his Fiction Factory. In early years he had The Writer, and then The Author. When these went the way of good but unprofitable things, The Editor fortunately happened along, and proved incomparably better in every detail.

From its initial number The Editor has been a monthly guest at the Factory, always cordially welcomed and given a place of honor. Guide, counsellor and friend – it has proved to be all these.

Edwards subscribes heartily to that benevolent policy known as "the helping hand." Furthermore, he tries to live up to it. What little success he has had with his Fiction Factory he has won by his own unaided efforts; but there were times, along at the beginning, when he could have avoided disappointment and useless labor if some one who knew had advised him. Realizing what "the helping hand" might have done in his own case, he has always felt the call to extend it to others. Assistance is useless, however, if a would-be writer hasn't something to say and doesn't know how to say it. Another who has had some success may secure the novice a considerate hearing, but from that on the matter lies wholly with the novice himself. If he has it in him, he will win; if he hasn't, he will fail. Edwards' first advice to those who have sought his help has invariably been this: "Subscribe to The Editor." In nearly every instance the advice has been taken, and with profitable results.

This same advice is given here, should the reader stand in need of a proper start along the thorny path of authorship. Nor is it to be construed in any manner as an advertisement. It is merely rendering justice where justice is due, and is an honest tribute to a publication for writers, drawn from an experience of twenty-two years "in the ranks."

XXII

NEW SOURCES

OF PROFIT

The out-put of the Fiction Factory brought excellent returns during the years 1908 and 1909. Industry followed close on the heels of opportunity and the result was more than gratifying. The 1908 product consisted of forty-four nickel novels for Harte & Perkins, two novelettes for The Blue Book, four serials for the Munsey publications, and one novelette for The People's Magazine. This work alone would have carried the receipts well above those of the preceding year, but new and unexpected sources of profit helped to enlarge the showing on the Factory's books.

The rapidity with which Edwards wrote his serial stories – sometimes under the spur of an immediate demand from his publishers, and sometimes under the less relentless spur of personal necessity – seemed to preclude the possibility of profit on a later publication "in cloth." Only a finished performance is worthy of a durable binding. Realizing this, Edwards had never made a determined effort to interest book-publishers in the stories. In the ordinary course of affairs, and with scarcely any attention on his part, two serials found their way into "cloth." "Danny W.," accepted and brought out by Dodd, Mead & Co., was written for book publication, and serialized after it had appeared in that form. It fell as far short of a "best seller" as did the two republished serials.

Nevertheless, in spite of the fact that additional profit through publication in cloth seemed out of the question, Edwards wondered if there were not something else to be gained from the stories besides the serial rights.