полная версия

полная версияThe Fiction Factory

The thermometer in Southern Arizona was "eighty in the shade" when Mr. and Mrs. Edwards, during the Christmas holidays, set their faces eastward. New York City, the shrine of so many pilgrims seeking prosperity, was their goal; and the metropolis, on that bleak New Year's Day that witnessed their arrival, was shivering in the grip of real, old-fashioned winter. The change from a balmy climate to blizzards and ice and a below-zero temperature brought Edwards to his bed with a vicious attack of rheumatism. For days while the little fund of $100 melted steadily away, he lay helpless.

The great city, in its dealings with impecunious strangers, has been painted in cruel colors. Edwards found this to be a mistake. On the occasion of their first visit to New York he and his wife had found quarters in a boarding house in Forty-fourth street. A pleasant landlady was in charge and the Edwards had won her friendship.

Here, forming one happy family, were actors and actresses, a salesman in a down-town department store, a stenographer, a travelling man for a bicycle house, and others. All were cheerful and kindly, and took occasion to drop in at the Edwards' third floor front and beguile the tedious hours for the invalid.

Fourteen years have brought many changes to Forty-fourth street between Broadway and Sixth avenue. The row of high-stoop brownstone "fronts" has that air of neglect which precedes demolition and the giving way of the old order to the new. The basement, where the pleasant landlady sat at her long table and smiled at the raillery and wit of "Beaney," and Sam, and "Smithy," and Ruth, and Ina and the rest, has fallen sadly from its high estate. A laundry has taken possession of the place. And "Beaney," the light-hearted one who laughed at his own misfortunes and sympathized with the misfortunes of others, "Beaney" has gone to his long account. A veil as impenetrable has fallen over the pleasant landlady, Sam, "Smithy," Ruth and Ina; and where-ever they may be, Edwards, remembering their kindness to him in his darkest days, murmurs for each and all of them a fervent "God bless you!"…

Before he was compelled to take to his bed Edwards had called at the offices of Harte & Perkins. His interview with Mr. Perkins impressed upon him the fact that, once a place upon the contributors' staff of a big publishing house is relinquished it is difficult to regain. Others had been given the work which Edwards had had for three years. These others were turning in acceptable manuscripts and, in justice to them, Harte & Perkins could not take the work out of their hands. Mr. Perkins, however, did give Edwards an order for four Five-Cent Libraries – stories to be held in reserve in case manuscripts from regular contributors failed to arrive in time. On Feb. 11 he received a letter from the firm to the following effect:

"When we wrote you day before yesterday asking you to turn in four Five-Cent Libraries before doing anything else in the Library line for us, we were under the impression that the gentleman who has been engaged upon this work for some time would not be able to turn the material in with usual regularity on account of illness, but we hear from him today that he is now in better health, and will be able to keep up with the work, which he is very anxious to do, and somewhat jealous of having any other material in the series so long as he can fill the bill. On this account it will be well for you to stop work on the Library. When you have completed the story on which you are now engaged, turn your attention to the Ten-Cent Library work, which we think you will be able to do to our satisfaction."

This will illustrate the attitude which some authors assume toward the "butter-in." All of a certain grist that comes to a publisher's mill must be their grist. If the mill ground for another, and found the product better than ordinary, the other might secure a "stand-in" that would threaten the prestige of the regular contributor.

In seeking to keep his head above water financially, Edwards attempted to sell book rights of "The Astrologer," the serial published in 1891 in The Detroit Free Press. He had written, also, 66 pages of a present-tense Gunteresque story which he hoped would win favor as had his other stories in that style. This yarn he called "Croesus, Jr." Both manuscripts were submitted to Harte & Perkins.

On Jan. 28, when the Edwards' exchequer was nearly depleted, "Croesus, Jr.," was returned with this written message:

"It might be said of the story in a way that it is readable, but it does not promise as good a story as we desire for this series. 'Most decidedly,' says the reader, 'it lacks originality, novelty and strength.' This criticism, which we consider entirely competent, must deter us from considering the story favorably."

This was blow number one. Blow number two was delivered Feb. 3:

"We have had your manuscript, 'The Astrologer,' examined, and the verdict is that it would not be suitable for any of our regular publications, and it is not in our line for book publication. The reader states that it very humorous in parts but rather long drawn out… We return manuscript."

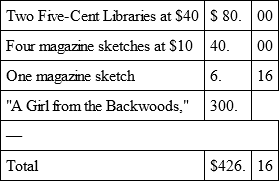

Two Five-Cent Libraries at $40 each were accepted and paid for; also four sketches written for a small magazine which Harte & Perkins were starting.5

Although he grew better of his rheumatism, Edwards failed to improve materially in health, and late in March he and his wife returned to Chicago. They rented a modest flat on the North Side, got their household effects out of storage, and faced the problem of existence with a courage scarcely warranted by their circumstances.

Edwards was able to work only half a day. The remainder of the day he spent in bed with an alternation of chills and fever and a grevious malady growing upon him. During this period he tried syndicating articles in the newspapers but without success. He also wrote for Harte & Perkins a "Guest" serial, the order for which he had brought back with him from New York. He made one try for this by submitting the first few chapters and synopsis of story which he called "A Vassar Girl." These were returned to him as unsuitable. He then wrote seven chapters of a serial entitled, "A Girl from the Backwoods," and – with much fear and trembling be it confessed – sent them on for examination. Under date of July 8 this word was returned:

"The seven chapters of 'A Girl from the Backwoods' read very good, and we should like to have you finish the story, and should it prove satisfactory in its entirety, we should consider it an acceptable story."

Here was encouragement at a time when encouragement was sorely needed. But how to keep the Factory going while the story was being finished was a difficult question. There were times when twenty-five cents had to procure a Sunday dinner for two; and there was a time when two country cousins arrived for a visit, and Edwards had not the half-dollar to pay an expressman for bringing their trunks from the station! Pride, be it understood, was one of Edwards' chief assets. He had always been a regal spender, and his country cousins knew it. How the lack of that fifty-cent piece grilled his sensitive soul!

It was during these trying times that the genius of Mrs. Edwards showed like a star in the heavy gloom. On next to nothing she contrived to supply the table, and the conjuring she could do with a silver dollar was a source of never-failing wonder to her husband.

Edwards remembers that, at a time when there was not even car-fare in the family treasury, a check for $1.50 arrived in payment for a 1,500-word story that had been out for several years.

During the latter part of July the demand for money pending the completion of "A Girl from the Backwoods" became so insistent, that Edwards wrote and submitted to Harte & Perkins a sketch for their magazine. It contained 1,232 words and was purchased on Aug. 3 for $6.16.

"A Girl from the Backwoods" was submitted late in September, and was returned on Oct. 13 for a small correction. The following letter, dated Oct. 27, was received from the editor of the "Guest:"

"The manuscript of 'A Girl from the Backwoods', also the correction which you have made, have been duly received. The correction is very satisfactory.

In regard to your suggestion about the heroine's name being that of a well known writer, we would say that inasmuch as the name is rather appropriate and suits the character we do not see that the lady who already bears it would in any way find fault with your use of it, and at present we think it may be allowed to stand."

As showing Edwards' pecuniary distress, the following paragraph from a letter from Harte & Perkins, dated Oct. 28, may be given:

"In response to your favor of the 19th and your telegram of yesterday,6 we enclose you herewith our check for $200 in full for your story 'A Girl from the Backwoods.' This is the best price we can make you for this and other stories of this class from your pen, and it is a somewhat better one than we are now paying for similar material from other writers. We believe this will be satisfactory to you."

The price was not satisfactory. Edwards and his wife had counted upon receiving at least $300 for the story, and they needed that amount sorely. A respectful letter at once went forward to Harte & Perkins, appealing to their sense of justice and fairness, which Edwards had never yet known to fail him. On Nov. 3 came an additional check for $100, and these words:

"Replying to your favor of Nov. 1st, at hand today, we beg to state that we shall, agreeably with your request and especially as you put it in such strong terms, make the payment on 'A Girl from the Backwoods' $300. The story is much liked by our reader and we do think it is worth as much if not more than the Stella Edwards material which, however, in the writer's judgement was much overpaid. We shall take this into account when considering the acceptance of other stories from your pen, and while we do not say positively that we will not pay $300 for the next one, as we wrote you in our last letter this is a high price for this class of material and we will expect to pay you according to our views as to the value of the manuscript."

The year closed with an order from Harte & Perkins for another story of the Stella Edwards sort; a very dismal year indeed, and showing Factory returns as follows:

Perhaps, after all, this was not doing so badly; for during this year, and the year immediately following, Edwards was to discover that he had had one foot in the grave. But his fortunes were at their lowest ebb. With 1898 they were to begin taking an upward turn.

Some one said that some one else, by using Ignatius Donnelly's cryptogram, proved that the late Bill Nye wrote the Shakespeare plays. This, of course, is merely a reflection on the cryptogram; BUT if Shakespeare's publishers had not been so slovenly with that folio edition of his plays, there would never have been any hunt for a cipher, nor any of this Bacon talk.

"In the early days, when I lived on the plains of Western Kansas on a homestead," says John H. Whitson, well and favorably known to dozens of editors, "I was nosed out by a correspondent for a Kansas City paper, who thought there was something bizarre in the fact that an author was living the simple life of a Western Settler. The purported interview he published was wonderful concoction! He gave a descriptive picture of the dug-out in which I lived, and filled in the gaps with other matter drawn from his imagination, making me out a sort of literary troglodyte; whereas, as a matter of fact, I had never lived in a dug-out. On top of it, one of my homesteading friends asked me in all seriousness how much I had paid to get that write-up and picture in the Kansas City paper, and seemed to think I was doing some tall lying when I said I had paid nothing."

XI

WHEN FICTION IS

STRANGER THAN TRUTH.

We are told that "fiction hath in it a higher end than fact," which we may readily believe; and we may also concede that "truth is stranger than fiction," at least in its occasional application. Nevertheless, in the course of his career as a writer Edwards has created two fictional fancies which so closely approximated truth as to make fiction stranger than truth; and, in one case, the net result of imagination was to coincide exactly with real facts of which the imagination could take no account. Perhaps each of these two instances is unique in its particular field; they are, in any event, so odd as to be worthy of note.

In the early 90's, when a great deal of Edwards' work was appearing, unsigned, in The Detroit Free Press, he wrote for that paper a brief sketch entitled, "The Fatal Hand." The sketch was substantially as follows:

"The Northern Pacific Railroad had just been built into Helena, Montana, and I happened to be in the town one evening and stepped into a gambling hall. Burton, a friend of mine, was playing poker with a miner and two professional gamblers. I stopped beside the table and watched the game.

Cards had just been drawn. Burton, as soon as he had looked at his hand, calmly shoved the cards together, laid them face-downward in front of him, removed a notebook from his pocket and scribbled something on a blank leaf. 'Read that,' said he, 'when you get back to your hotel tonight.'

The play proceeded. Presently the miner detected one of the professional gamblers in the act of cheating. Words were passed, the lie given. All the players leaped to their feet. Burton, in attempting to keep the miner from shooting, received the gambler's bullet and fell dead upon the scattered cards.

An hour later, when I reached my hotel, I thought of the note Burton had handed me. It read: 'I have drawn two red sevens. I now hold jacks full on red sevens. It is a fatal hand and I shall never leave this table alive. I have $6,000 in the First National Bank at Bismarck. Notify my mother, Mrs. Ezra J. Burton, Louisville, Kentucky.'"

This small product of the Fiction Factory was pure fiction from beginning to end. In the original it had the tang of point and counterpoint which caused it to be seized upon by other papers and widely copied. This gave extensive publicity to the "fatal hand" – the three jacks and two red sevens contrived by Edwards out of a small knowledge of poker and the cabala of cards.

Yet, what was the result?

A month later the Chicago papers published an account of a police raid on a gambling room. As the officers rushed into the place a man at one of the tables fell forward and breathed his last. "Heart disease," was the verdict. But note: A police officer looked at the cards the dead man had held and found them to be three jacks and two red sevens.

A week later The New York Recorder gave space to a news story in which a man was slain at a gaming table in Texas. When the smoke of the shooting had blown away some one made the discovery that he had held the fatal hand.

From that time on for several months the fatal hand left a trail of superstition and gore all over the West. How many murders and hopeless attacks of heart failure it was responsible for Edwards had no means of knowing, but he could scarcely pick up a paper without finding an account of some of the ravages caused by his "jacks full on red sevens."

Query: Were the reporters of the country romancing? If not, will some psychologist kindly rise and explain how a bit of fiction could be responsible for so much real tragedy?

In this instance, fancy established a precedent for fact; in the case that follows, the frankly fictitious paralleled the unknown truth in terms so exact that the story was recognized and appropriated by the son of the story's hero.

While Edwards was in Arizona he was continually on the alert for story material. The sun, sand and solitude of the country "God forgot" produce types to be found nowhere else. He ran out many a trail that led from adobe-walled towns into waterless deserts and bleak, cacti-covered hills to end finally at some mine or cattle camp. It was on one of these excursions that he was told how a company of men had built a dam at a place called Walnut Grove. This dam backed up the waters of a river and formed a huge lake. Mining for gold by the hydraulic method was carried on profitably in the river below the dam. One night the dam "went out" and a number of laborers were drowned.

With this as the germ of the plot Edwards worked out a story. He called it "A Study in Red," and it purported to show how a lazy Maricopa Indian, loping along on his pony in the gulch below Walnut Grove, gave up his mount to a white girl, daughter of the superintendent of the mining company, and while she raced on to safety he remained to die in the flood from the broken dam.

The story was published in Munsey's Magazine. Six years later the author received a letter from the Maricopa Indian Reservation, sent to New York in care of the F. A. Munsey Company. The letter was from a young Maricopa.

"I have often read the account of my father's bravery, and how he saved the life of the beautiful white girl when the Walnut Grove dam gave way. I have kept the magazine, and whenever I feel blue, or life does not go to please me, I get the story and read it and take heart to make the best of my lot and try to pattern after my father.

I have long wanted to write you, and now I have done so. I am back from the Indian School at Carlisle, on a visit to my people, and am impelled to send you this letter of appreciation and thanks for the story about my father."

Now, pray, what is one to think of this? The letter bears all the earmarks of a bona fide performance and was written and mailed on the Reservation. Edwards' fiction, it seems, had become sober fact for this young Maricopa Indian. Or did his father really die by giving up his pony to the "beautiful young white girl?" And was Edwards' prescience doing subliminal stunts when he wrote the story?

John Peter, should this ever meet your eyes will you please communicate further with the author of "A Study in Red?" It has been some years now since a letter, sent to you at the Reservation, failed of a reply. And the letter has not been returned.

XII

FORTUNE BEGINS

TO SMILE

Edwards' literary fortunes all but reached financial zero in 1897; with 1898 they began to mount, although the tendency upward was not very pronounced until the month of April. During the first quarter of the year he wrote and sold one Stella Edwards serial entitled "Lovers En Masque." His poor health continued, and he was able to work only a few hours each day, but the fact that he could drive himself to the typewriter and lash his wits into evolving acceptable work gave him encouragement to keep at it. Early in April, with part of the proceeds from the serial story for expenses, he made a trip to New York.

"Prospecting trips" is the name Edwards gives to his frequent journeys to the publishing center of the country. He prospected for orders, prospected for better prices, prospected for new markets. No fiction factory can be run successfully on a haphazard system for disposing of its product. There must be some market in prospect, and on the wheel of this demand the output must be shaped as the potter shapes his clay.

Edwards made it a rule to meet his publishers once a year, secure their personal views as he could not secure them through correspondence, and keep himself prominently before them. In this way he secured commissions which, undoubtedly, would otherwise have been placed elsewhere. With each succeeding journey Edwards has made to New York, his prospecting trips have profited him more and more. This is as it should be. There is no "marking time" for a writer in the fierce competition for editorial favor; for one merely to "hold his own" is equivalent to losing ground. The writer must grow in his work. When he ceases to do that he will find himself slipping steadily backward toward oblivion.

Edwards found that in reaching New York in early April 1898, he had arrived at the psychological moment. Harte & Perkins, already described as keeping tense fingers on the pulse of their reading public, had discovered a feverish quickening of interest for which the Klondike gold rush was responsible. The prognosis was good for a new five-cent library; so the "Golden Star Library" was given to the presses. Edwards, because he was on the spot and urging his claims for recognition, was chosen to furnish the copy. During the year he wrote sixteen of these stories.

For half of April and all of May and June, Edwards and his wife were at their old boarding place in Forty-fourth street. During this time, along with the writing of the Golden Star stories, a juvenile serial and a Stella Edwards serial were prepared. The title of the Stella Edwards rhapsody was "A Blighted Heart."

On July 2, owing to the excessive heat in the city and a belief on Edwards' part that the country would benefit him, the Fiction Factory was temporarily removed to the Catskill Mountains. Comfortable quarters were secured in a hotel near Cairo, and the work of producing copy went faithfully on. Edwards' health improved somewhat, although he was still unable to keep at his machine for a union day of eight hours.

Under date of Aug. 1, Harte & Perkins wrote Edwards that on account of the poor success of the Golden Star Library they would have to stop its weekly publication and issue it as a monthly. Mr. Perkins write:

"I do not think that the quality of the manuscript is so much at fault as the character of the library itself, though it is very difficult always to know just what the boys want."

Edwards was depending upon this library to support himself and wife, and the weekly check was a sine qua non. Summer-resorting is expensive, and he had not yet had his fill of the historic old Catskills. He wrote the firm and requested them to send on a check for "A Blighted Heart." The blight did not confine itself to the story but was visited upon Edwards' hopes, as well. Harte & Perkins did not respond favorably. The serial was not to begin in "The Weekly Guest" until the latter part of September, and upon beginning publication was to be paid for in weekly installments of $25. Wrote Mr. Perkins:

"This is a season when, with depressed business and the many accounts we have to look after, it is difficult for us to make advanced payments on manuscripts. You may rest assured that, if conditions were otherwise, I should have been glad to meet your wishes."

This meant an immediate farewell to the stamping grounds of good old Rip Van Winkle. Forthwith the Edwards struck their tent and boarded a night boat at Catskill Landing for down river. In their stateroom that night, with a fountain pen and using the wash-stand for a table, Edwards completed No. 16 of the ill-fated Golden Star Library. He had begun this manuscript before the notification to stop work on the series had reached him. In such cases, Harte & Perkins never refused to accept the complete story.

December found Edwards again settled on the North Side, in Chicago. He had consulted a physician regarding his health, and after a thorough examination had been told that it would require at least a year, and perhaps a year and a half, to cure him. The physician was a young man of splendid ability, and as he had just "put out his shingle" and patients were slow in rallying "round the standard," he threw himself heart and soul into the task of making a whole man out of Edwards. The writer helped by leasing a flat within half a block of his medical adviser and faced the twelve or eighteen months to come with more or less equanimity.

Edwards, of course, could not recline at his ease while the work of rehabilitation was going forward. The family must be supported and the doctor paid. Forty dollars a month from the Golden Star Library would not do this. It was necessary to run up the returns somehow and another Stella Edwards story was undertaken. The title of this story was "Won by Love," and Harte & Perkins acknowledged receipt of the first two installments on Dec. 6. Inasmuch as "Won by Love" came very near being the death of its author, it may be interesting to consider the story a little further. The letter of the 6th ran: