полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

The great preacher Jonathan Mayhew had recommended such a step to James Otis in 1766, and he was led to it through his experience of church matters. Writing in haste, on a Sunday morning, he said, “To a good man all time is holy enough; and none is too holy to do good, or to think upon it. Cultivating a good understanding and hearty friendship between these colonies appears to me so necessary a part of prudence and good policy that no favourable opportunity for that purpose should be omitted… You have heard of the communion of churches: … while I was thinking of this in my bed, the great use and importance of a communion of colonies appeared to me in a strong light, which led me immediately to set down these hints to transmit to you.” The plan which Mayhew had in mind was the establishment of a regular system of correspondence whereby the colonies could take combined action in defence of their liberties. In the grand crisis of 1772, Samuel Adams saw how much might be effected through committees of correspondence that could not well be effected through the ordinary governmental machinery of the colonies. At the October town meeting in Boston, a committee was appointed to ask the governor whether the judges’ salaries were to be paid in conformity to the royal order; and he was furthermore requested to convoke the assembly, in order that the people might have a chance to express their views on so important a matter. But Hutchinson told the committee to mind its own business: he refused to say what would be done about the salaries, and denied the right of the town to petition for a meeting of the assembly. Massachusetts was thus virtually without a general government at a moment when the public mind was agitated by a question of supreme importance.

The committees of correspondence in MassachusettsSamuel Adams thereupon in town meeting moved the appointment of a committee of correspondence, “to consist of twenty-one persons, to state the rights of the colonists and of this province in particular, as men and Christians and as subjects; and to communicate and publish the same to the several towns and to the world as the sense of this town, with the infringements and violations thereof that have been, or from time to time may be, made.” The adoption of this measure at first excited the scorn of Hutchinson, who described the committee as composed of “deacons,” “atheists,” and “black-hearted fellows,” whom one would not care to meet in the dark. He predicted that they would only make themselves ridiculous, but he soon found reason to change his mind. The response to the statements of the Boston committee was prompt and unanimous, and before the end of the year more than eighty towns had already organized their committees of correspondence. Here was a new legislative body, springing directly from the people, and competent, as events soon showed, to manage great affairs. Its influence reached into every remotest corner of Massachusetts, it was always virtually in session, and no governor could dissolve or prorogue it. Though unknown to the law, the creation of it involved no violation of law. The right of the towns of Massachusetts to ask one another’s advice could no more be disputed than the right of the freemen of any single town to hold a town meeting. The power thus created was omnipresent, but intangible.

“This,” said Daniel Leonard, the great Tory pamphleteer, two years afterwards, “is the foulest, subtlest, and most venomous serpent ever issued from the egg of sedition. It is the source of the rebellion. I saw the small seed when it was planted: it was a grain of mustard. I have watched the plant until it has become a great tree. The vilest reptiles that crawl upon the earth are concealed at the root; the foulest birds of the air rest upon its branches. I would now induce you to go to work immediately with axes and hatchets and cut it down, for a twofold reason, – because it is a pest to society, and lest it be felled suddenly by a stronger arm, and crush its thousands in its fall.”

Intercolonial committees of correspondenceThe system of committees of correspondence did indeed grow into a mighty tree; for it was nothing less than the beginning of the American Union. Adams himself by no means intended to confine his plan to Massachusetts, for in the following April he wrote to Richard Henry Lee of Virginia urging the establishment of similar committees in every colony. But Virginia had already acted in the matter. When its assembly met in March, 1773, the news of the refusal of Hopkins to obey the royal order, of the attack upon the Massachusetts judiciary, and of the organization of the committees of correspondence was the all-exciting subject of conversation. The motion to establish a system of intercolonial committees of correspondence was made by the youthful Dabney Carr, and eloquently supported by Patrick Henry and Richard Henry Lee. It was unanimously adopted, and very soon several other colonies elected committees, in response to the invitation from Virginia.

This was the most decided step toward revolution that had yet been taken by the Americans. It only remained for the various intercolonial committees to assemble together, and there would be a Congress speaking in the name of the continent. To bring about such an act of union, nothing more was needed than some fresh course of aggression on the part of the British government which should raise a general issue in all the colonies; and, with the rare genius for blundering which had possessed it ever since the accession of George III., the government now went on to provide such an issue. It was preëminently a moment when the question of taxation should have been let alone. Throughout the American world there was a strong feeling of irritation, which might still have been allayed had the ministry shown a yielding temper. The grounds of complaint had come to be different in the different colonies, and in some cases, in which we can clearly see the good sense of Lord North prevailing over the obstinacy of the king, the ministry had gained a point by yielding. In the Rhode Island case, they had seized a convenient opportunity and let the matter drop, to the manifest advantage of their position.

The question of taxation revivedIn Massachusetts, the discontent had come to be alarming, and it was skilfully organized. The assembly had offered the judges their salaries in the usual form, and had threatened to impeach them if they should dare to accept a penny from the Crown. The recent action of Virginia had shown that these two most powerful of the colonies were in strong sympathy with one another. It was just this moment that George III. chose for reviving the question of taxation, upon which all the colonies would be sure to act as a unit, and sure to withstand him to his face. The duty on tea had been retained simply as a matter of principle. It did not bring three hundred pounds a year into the British exchequer. But the king thought this a favourable time for asserting the obnoxious principle which the tax involved.

Thus, as in Mrs. Gamp’s case, a teapot became the cause or occasion of a division between friends. The measures now taken by the government brought matters at once to a crisis. None of the colonies would take tea on its terms.

Lord Hillsborough had lately been superseded as colonial secretary by Lord Dartmouth, an amiable man like the prime minister, but like him wholly under the influence of the king. Lord Dartmouth’s appointment was made the occasion of introducing a series of new measures. The affairs of the East India Company were in a bad condition, and it was thought that the trouble was partly due to the loss of the American trade in tea. The Americans would not buy tea shipped from England, but they smuggled it freely from Holland, and the smuggling could not be stopped by mere force. The best way to obviate the difficulty, it was thought, would be to make English tea cheaper in America than foreign tea, while still retaining the duty of threepence on a pound. If this could be achieved, it was supposed that the Americans would be sure to buy English tea by reason of its cheapness, and would thus be ensnared into admitting the principle involved in the duty.

The king’s ingenious schemeThis ingenious scheme shows how unable the king and his ministers were to imagine that the Americans could take a higher view of the matter than that of pounds, shillings, and pence. In order to enable the East India Company to sell its tea cheap in America, a drawback was allowed of all the duties which such tea had been wont to pay on entering England on its way from China. In this way, the Americans would now find it actually cheaper to buy the English tea with the duty on it than to smuggle their tea from Holland. To this scheme, Lord North said, it was of no use for any one to offer objections, for the king would have it so. “The king meant to try the question with America.” In accordance with this policy, several ships loaded with tea set sail in the autumn of 1773 for the four principal ports, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston. Agents or consignees of the East India Company were appointed by letter to receive the tea in these four towns.

As soon as the details of this scheme were known in America, the whole country was in a blaze, from Maine to Georgia. Nevertheless, only legal measures of resistance were contemplated. In Philadelphia, a great meeting was held in October at the State House, and it was voted that whosoever should lend countenance to the receiving or unloading of the tea would be regarded as an enemy to his country. The consignees were then requested to resign their commissions, and did so.

How Boston became the battle-groundIn New York and Charleston, also, the consignees threw up their commissions. In Boston, a similar demand was made, but the consignees doggedly refused to resign; and thus the eyes of the whole country were directed toward Boston as the battlefield on which the great issue was to be tried.

LORD NORTH POURING TEA DOWN COLUMBIA’S THROAT

During the month of November many town meetings were held in Faneuil Hall. On the 17th, authentic intelligence was brought that the tea-ships would soon arrive. The next day, a committee, headed by Samuel Adams, waited upon the consignees, and again asked them to resign. Upon their refusal, the town meeting instantly dissolved itself, without a word of comment or debate; and at this ominous silence the consignees and the governor were filled with a vague sense of alarm, as if some storm were brewing whereof none could foresee the results.

The five towns ask adviceAll felt that the decision now rested with the committees of correspondence. Four days afterward, the committees of Cambridge, Brookline, Roxbury, and Dorchester met the Boston committee at Faneuil Hall, and it was unanimously resolved that on no account should the tea be landed. The five towns also sent a letter to all the other towns in the colony, saying, “Brethren, we are reduced to this dilemma: either to sit down quiet under this and every other burden that our enemies shall see fit to lay upon us, or to rise up and resist this and every plan laid for our destruction, as becomes wise freemen. In this extremity we earnestly request your advice.” There was nothing weak or doubtful in the response. From Petersham and Lenox perched on their lofty hilltops, from the valleys of the Connecticut and the Merrimack, from Chatham on the bleak peninsula of Cape Cod, there came but one message, – to give up life and all that makes life dear, rather than submit like slaves to this great wrong. Similar words of encouragement came from other colonies. In Philadelphia, at the news of the bold stand Massachusetts was about to take, the church-bells were rung, and there was general rejoicing about the streets. A letter from the men of Philadelphia to the men of Boston said, “Our only fear is lest you may shrink. May God give you virtue enough to save the liberties of your country.”

On Sunday, the 28th, the Dartmouth, first of the tea-ships, arrived in the harbour. The urgency of the business in hand overcame the sabbatarian scruples of the people.

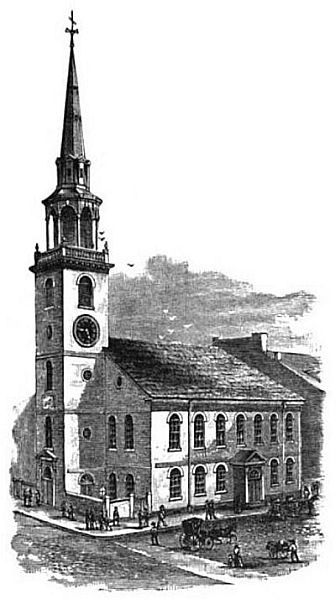

Arrival of the tea; meeting at the Old SouthThe committee of correspondence met at once, and obtained from Francis Rotch, the owner of the vessel, a promise that the ship should not be entered before Tuesday. Samuel Adams then invited the committees of the five towns, to which Charlestown was now added, to hold a mass-meeting the next morning at Faneuil Hall. More than five thousand people assembled, but as the Cradle of Liberty could not hold so many, the meeting was adjourned to the Old South Meeting-House. It was voted, without a single dissenting voice, that the tea should be sent back to England in the ship which had brought it. Rotch was forbidden to enter the ship at the Custom House, and Captain Hall, the ship’s master, was notified that “it was at his peril if he suffered any of the tea brought by him to be landed.” A night-watch of twenty-five citizens was set to guard the vessel, and so the meeting adjourned till next day, when it was understood that the consignees would be ready to make some proposals in the matter. Next day, the message was brought from the consignees that it was out of their power to send back the tea; but if it should be landed, they declared themselves willing to store it, and not expose any of it for sale until word could be had from England. Before action could be taken upon this message, the sheriff of Suffolk county entered the church and read a proclamation from the governor, warning the people to disperse and “surcease all further unlawful proceedings at their utmost peril.” A storm of hisses was the only reply, and the business of the meeting went on. The proposal of the consignees was rejected, and Rotch and Hall, being present, were made to promise that the tea should go back to England in the Dartmouth, without being landed or paying duty. Resolutions were then passed, forbidding all owners or masters of ships to bring any tea from Great Britain to any part of Massachusetts, so long as the act imposing a duty on it remained unrepealed. Whoever should disregard this injunction would be treated as an enemy to his country, his ships would be prevented from landing – by force, if necessary – and his tea would be sent back to the place whence it came. It was further voted that the citizens of Boston and the other towns here assembled would see that these resolutions were carried into effect, “at the risk of their lives and property.” Notice of these resolutions was sent to the owners of the other ships, now daily expected. And, to crown all, a committee, of which Adams was chairman, was appointed to send a printed copy of these proceedings to New York and Philadelphia, to every seaport in Massachusetts, and to the British government.

Two or three days after this meeting, the other two ships arrived, and, under orders from the committee of correspondence, were anchored by the side of the Dartmouth, at Griffin’s Wharf, near the foot of Pearl Street.

The tea-ships placed under guardA military watch was kept at the wharf day and night, sentinels were placed in the church belfries, chosen post-riders, with horses saddled and bridled, were ready to alarm the neighbouring towns, beacon-fires were piled all ready for lighting upon every hilltop, and any attempt to land the tea forcibly would have been the signal for an instant uprising throughout at least four counties. Now, in accordance with the laws providing for the entry and clearance of shipping at custom houses, it was necessary that every ship should land its cargo within twenty days from its arrival. In case this was not done, the revenue officers were authorized to seize the ship and land its cargo themselves. In the case of the Dartmouth, the captain had promised to take her back to England without unloading; but still, before she could legally start, she must obtain a clearance from the collector of customs, or, in default of this, a pass from the governor. At sunrise of Friday, the 17th of December, the twenty days would have expired.

THE OLD SOUTH MEETING-HOUSE

On Saturday, the 11th, Rotch was summoned before the committee of correspondence, and Samuel Adams asked him why he had not kept his promise, and started his ship off for England. He sought to excuse himself on the ground that he had not the power to do so, whereupon he was told that he must apply to the collector for a clearance. Hearing of these things, the governor gave strict orders at the Castle to fire upon any vessel trying to get out to sea without a proper permit; and two ships from Montagu’s fleet, which had been laid up for the winter, were stationed at the entrance of the harbour, to make sure against the Dartmouth’s going out. Tuesday came, and Rotch, having done nothing, was summoned before the town meeting, and peremptorily ordered to apply for a clearance. Samuel Adams and nine other gentlemen accompanied him to the Custom House to witness the proceedings, but the collector refused to give an answer until the next day. The meeting then adjourned till Thursday, the last of the twenty days. On Wednesday morning, Rotch was again escorted to the Custom House, and the collector refused to give a clearance unless the tea should first be landed.

TABLE AND CHAIR FROM GOVERNOR HUTCHINSON’S HOUSE AT MILTON

Town meeting at the Old South

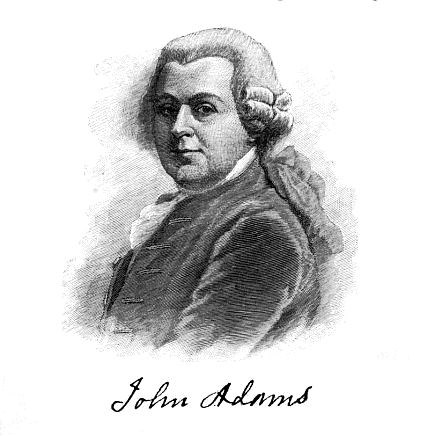

On the morning of Thursday, December 16th, the assembly which was gathered in the Old South Meeting-House, and in the streets about it, numbered more than seven thousand people. It was to be one of the most momentous days in the history of the world. The clearance having been refused, nothing now remained but to order Rotch to request a pass for his ship from the governor. But the wary Hutchinson, well knowing what was about to be required of him, had gone out to his country house at Milton, so as to foil the proceedings by his absence. But the meeting was not to be so trifled with. Rotch was enjoined, on his peril, to repair to the governor at Milton, and ask for his pass; and while he was gone, the meeting considered what was to be done in case of a refusal. Without a pass it would be impossible for the ship to clear the harbour under the guns of the Castle; and by sunrise, next morning, the revenue officers would be empowered to seize the ship, and save by a violent assault upon them it would be impossible to prevent the landing of the tea. “Who knows,” said John Rowe, “how tea will mingle with salt water?” And great applause followed the suggestion. Yet the plan which was to serve as a last resort had unquestionably been adopted in secret committee long before this. It appears to have been worked out in detail in a little back room at the office of the “Boston Gazette,” and there is no doubt that Samuel Adams, with some others of the popular leaders, had a share in devising it. But among the thousands present at the town meeting, it is probable that very few knew just what it was designed to do. At five in the afternoon, it was unanimously voted that, come what would, the tea should not be landed. It had now grown dark, and the church was dimly lighted with candles. Determined not to act until the last legal method of relief should have been tried and found wanting, the great assembly was still waiting quietly in and about the church when, an hour after nightfall, Rotch returned from Milton with the governor’s refusal. Then, amid profound stillness, Samuel Adams arose and said, quietly but distinctly, “This meeting can do nothing more to save the country.” It was the declaration of war; the law had shown itself unequal to the occasion, and nothing now remained but a direct appeal to force.

The tea thrown into the harbourScarcely had the watchword left his mouth when a war-whoop answered from outside the door, and fifty men in the guise of Mohawk Indians passed quickly by the entrance, and hastened to Griffin’s Wharf. Before the nine o’clock bell rang, the three hundred and forty-two chests of tea laden upon the three ships had been cut open, and their contents emptied into the sea. Not a person was harmed; no other property was injured; and the vast crowd, looking upon the scene from the wharf in the clear frosty moonlight, was so still that the click of the hatchets could be distinctly heard. Next morning, the salted tea, as driven by wind and wave, lay in long rows on Dorchester beach, while Paul Revere, booted and spurred, was riding post-haste to Philadelphia, with the glorious news that Boston had at last thrown down the gauntlet for the king of England to pick up.

This heroic action of Boston was greeted with public rejoicing throughout all the thirteen colonies, and the other principal seaports were not slow to follow the example. A ship laden with two hundred and fifty-seven chests of tea had arrived at Charleston on the 2d of December; but the consignees had resigned, and after twenty days the ship’s cargo was seized and landed; and so, as there was no one to receive it, or pay the duty, it was thrown into a damp cellar, where it spoiled. In Philadelphia, on the 25th, a ship arrived with tea; but a meeting of five thousand men forced the consignees to resign, and the captain straightway set sail for England, the ship having been stopped before it had come within the jurisdiction of the custom house.

Grandeur of the Boston Tea PartyIn Massachusetts, the exultation knew no bounds. “This,” said John Adams, “is the most magnificent movement of all. There is a dignity, a majesty, a sublimity, in this last effort of the patriots that I greatly admire.” Indeed, often as it has been cited and described, the Boston Tea Party was an event so great that even American historians have generally failed to do it justice. This supreme assertion by a New England town meeting of the most fundamental principle of political freedom has been curiously misunderstood by British writers, of whatever party. The most recent Tory historian, Mr. Lecky,[2] speaks of “the Tea-riot at Boston,” and characterizes it as an “outrage.” The most recent Liberal historian, Mr. Green, alludes to it as “a trivial riot.” Such expressions betray most profound misapprehension alike of the significance of this noble scene and of the political conditions in which it originated. There is no difficulty in defining a riot. The pages of history teem with accounts of popular tumults, wherein passion breaks loose and wreaks its fell purpose, unguided and unrestrained by reason. No definition could be further from describing the colossal event which occurred in Boston on the 16th of December, 1773. Here passion was guided and curbed by sound reason at every step, down to the last moment, in the dim candle-light of the old church, when the noble Puritan statesman quietly told his hearers that the moment for using force had at last, and through no fault of theirs, arrived. They had reached a point where the written law had failed them; and in their effort to defend the eternal principles of natural justice, they were now most reluctantly compelled to fall back upon the paramount law of self-preservation. It was the one supreme moment in a controversy supremely important to mankind, and in which the common-sense of the world has since acknowledged that they were wholly in the right. It was the one moment of all that troubled time in which no compromise was possible. “Had the tea been landed,” says the contemporary historian, William Gordon, “the union of the colonies in opposing the ministerial scheme would have been dissolved; and it would have been extremely difficult ever after to have restored it.” In view of the stupendous issues at stake, the patience of the men of Boston was far more remarkable than their boldness. For the quiet sublimity of reasonable but dauntless moral purpose, the heroic annals of Greece and Rome can show us no greater scene than that which the Old South Meeting-House witnessed on the day when the tea was destroyed.