полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

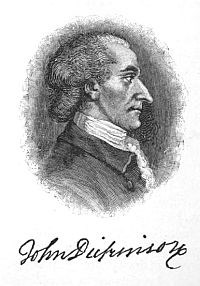

In these letters, Dickinson held a position quite similar to that occupied by Burke. Recognizing that the constitutional relations of the colonies to the mother-country had always been extremely vague and ill-defined, he urged that the same state of things be kept up forever through a genuine English feeling of compromise, which should refrain from pushing any abstract theory of sovereignty to its extreme logical conclusions. At the same time, he declared that the Townshend revenue acts were “a most dangerous innovation” upon the liberties of the people, and significantly hinted, that, should the ministry persevere in its tyrannical policy, “English history affords examples of resistance by force.”

The Massachusetts circular letterWhile Dickinson was publishing these letters, Samuel Adams wrote for the Massachusetts assembly a series of addresses to the ministry, a petition to the king, and a circular letter to the assemblies of the other colonies. In these very able state papers, Adams declared that a proper representation of American interests in the British Parliament was impracticable, and that, in accordance with the spirit of the English Constitution, no taxes could be levied in America except by the colonial legislatures. He argued that the Townshend acts were unconstitutional, and asked that they should be repealed, and that the colonies should resume the position which they had occupied before the beginning of the present troubles.

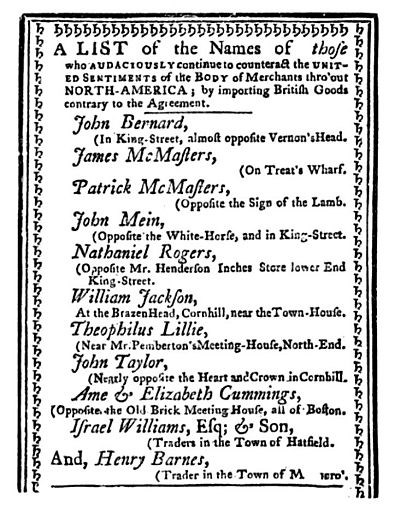

The petition to the king was couched in beautiful and touching language, but the author seems to have understood very well how little effect it was likely to produce. His daughter, Mrs. Wells, used to tell how one evening, as her father had just finished writing this petition, and had taken up his hat to go out, she observed that the paper would soon be touched by the royal hand. “More likely, my dear,” he replied, “it will be spurned by the royal foot!” Adams rightly expected much more from the circular letter to the other colonies, in which he invited them to coöperate with Massachusetts in resisting the Townshend acts, and in petitioning for their repeal. The assembly, having adopted all these papers by a large majority, was forthwith prorogued by Governor Bernard, who, in a violent speech, called them demagogues to whose happiness “everlasting contention was necessary.” But the work was done. The circular letter brought encouraging replies from the other colonies. The condemnation of the Townshend acts was unanimous, and leading merchants in most of the towns entered into agreements not to import any more English goods until the acts should be repealed. Ladies formed associations, under the name of Daughters of Liberty, pledging themselves to wear homespun clothes and to abstain from drinking tea. The feeling of the country was thus plainly enough expressed, but nowhere as yet was there any riot or disorder, and no one as yet, except, perhaps, Samuel Adams, had begun to think of a political separation from England. Even he did not look upon such a course as desirable, but the treatment of his remonstrances by the king and the ministry soon led him to change his opinion.

The petition of the Massachusetts assembly was received by the king with silent contempt, but the circular letter threw him into a rage. In cabinet meeting, it was pronounced to be little better than an overt act of rebellion, and the ministers were encouraged in this opinion by letters from Bernard, who represented the whole affair as the wicked attempt of a few vile demagogues to sow the seeds of dissension broadcast over the continent. We have before had occasion to observe the extreme jealousy with which the Crown had always regarded any attempt at concerted action among the colonies which did not originate with itself.

Lord Hillsborough’s instructions to BernardBut here was an attempt at concerted action in flagrant opposition to the royal will. Lord Hillsborough instructed Bernard to command the assembly to rescind their circular letter, and, in case of their refusal, to send them home about their business. This was to be repeated year after year, so that, until Massachusetts should see fit to declare herself humbled and penitent, she must go without a legislature. At the same time, Hillsborough ordered the assemblies in all the other colonies to treat the Massachusetts circular with contempt, – and this, too, under penalty of instant dissolution. From a constitutional point of view, these arrogant orders deserve to be ranked among the curiosities of political history. They serve to mark the rapid progress the ministry was making in the art of misgovernment. A year before, Townshend had suspended the New York legislature by an act of Parliament. Now, a secretary of state, by a simple royal order, threatened to suspend all the legislative bodies of America unless they should vote according to his dictation.

When Hillsborough’s orders were laid before the Massachusetts assembly, they were greeted with scorn. “We are asked to rescind,” said Otis. “Let Britain rescind her measures, or the colonies are lost to her forever.”

The “Illustrious Ninety-Two”Nevertheless, it was only after nine days of discussion that the question was put, when the assembly decided, by a vote of ninety-two to seventeen, that it would not rescind its circular letter. Bernard immediately dissolved the assembly, but its vote was hailed with delight throughout the country, and the “Illustrious Ninety-Two” became the favourite toast on all convivial occasions. Nor were the other colonial assemblies at all readier than that of Massachusetts to yield to the secretary’s dictation. They all expressed the most cordial sympathy with the recommendations of the circular letter; and in several instances they were dissolved by the governors, according to Hillsborough’s instructions.

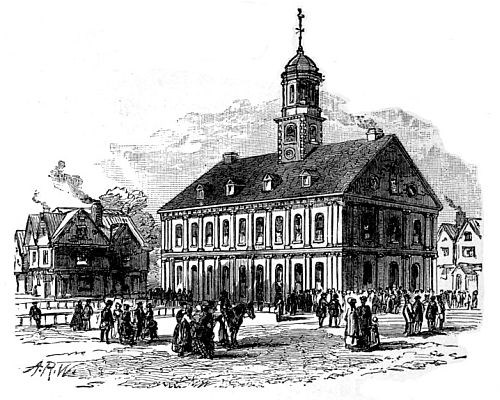

FANEUIL HALL, THE CRADLE OF LIBERTY

While these fruitless remonstrances against the Townshend acts had been preparing, the commissioners of the customs, in enforcing the acts, had not taken sufficient pains to avoid irritating the people.

Impressment of citizensIn the spring of 1768, the fifty-gun frigate Romney had been sent to mount guard in the harbour of Boston, and while she lay there several of the citizens were seized and impressed as seamen, – a lawless practice long afterward common in the British navy, but already stigmatized as barbarous by public opinion in America. As long ago as 1747, when the relations between the colonies and the home government were quite harmonious, resistance to the press-gang had resulted in a riot in the streets of Boston. Now while the town was very indignant over this lawless kidnapping of its citizens, on the 10th of June, 1768, John Hancock’s sloop Liberty was seized at the wharf by a boat’s crew from the Romney, for an alleged violation of the revenue laws, though without official warrant. Insults and recriminations ensued between the officers and the citizens assembled on the wharf, until after a while the excitement grew into a mild form of riot, in which a few windows were broken, some of the officers were pelted, and finally a pleasure boat, belonging to the collector, was pulled up out of the water, carried to the Common, and burned there, when Hancock and Adams, arriving upon the scene, put a stop to the commotion. A few days afterward, a town meeting was held in Faneuil Hall; but as the crowd was too great to be contained in the building, it was adjourned to the Old South Meeting-House, where Otis addressed the people from the pulpit. A petition to the governor was prepared, in which it was set forth that the impressment of peaceful citizens was an illegal act, and that the state of the town was as if war had been declared against it; and the governor was requested to order the instant removal of the frigate from the harbour. A committee of twenty-one leading citizens was appointed to deliver this petition to the governor at his house in Jamaica Plain. In his letters to the secretary of state Bernard professed to live in constant fear of assassination, and was always begging for troops to protect him against the incendiary and blackguard mob of Boston. Yet as he looked down the beautiful road from his open window, that summer afternoon, what he saw was not a ragged mob, armed with knives and bludgeons, shouting “Liberty, or death!” and bearing the head of a revenue collector aloft on the point of a pike, but a quiet procession of eleven chaises, from which there alighted at his door twenty-one gentlemen, as sedate and stately in demeanour as those old Roman senators at whom the Gaulish chief so marvelled. There followed a very affable interview, during which wine was passed around. The next day the governor’s answer was read in town meeting, declining to remove the frigate, but promising that in future there should be no impressment of Massachusetts citizens; and with this compromise the wrath of the people was for a moment assuaged.

Affairs of this sort, reported with gross exaggeration by the governor and revenue commissioners to the ministry, produced in England the impression that Boston was a lawless and riotous town, full of cutthroats and blacklegs, whose violence could be held in check only by martial law. Of all the misconceptions of America by England which brought about the American Revolution, perhaps this notion of the turbulence of Boston was the most ludicrous. During the ten years of excitement which preceded the War of Independence there was one disgraceful riot in Boston, – that in which Hutchinson’s house was sacked; but in all this time not a drop of blood was shed by the people, nor was anybody’s life for a moment in danger at their hands. The episode of the sloop Liberty, as here described, was a fair sample of the disorders which occurred at Boston at periods of extreme excitement; and in any European town in the eighteenth century it would hardly have been deemed worthy of mention.

Even before the affair of the Liberty, the government had made up its mind to send troops to Boston, in order to overawe the popular party and show them that the king and Lord Hillsborough were in earnest. The news of the Liberty affair, however, served to remove any hesitation that might hitherto have been felt.

Statute of Henry VIII. concerning “treason committed abroad”Vengeance was denounced against the insolent town of Boston. The most seditious spirits, such as Otis and Adams, must be made an example of, and thus the others might be frightened into submission. With such intent, Lord Hillsborough sent over to inquire “if any person had committed any acts which, under the statutes of Henry VIII. against treason committed abroad, might justify their being brought to England for trial.” This raking-up of an obsolete statute, enacted at one of the worst periods of English history, and before England had any colonies at all, was extremely injudicious. But besides all this, continued Hillsborough, the town meeting, that nursery of sedition, must be put down or overawed; and in pursuance of this scheme, two regiments of soldiers and a frigate were to be sent over to Boston at the ministry’s earliest convenience. To make an example of Boston, it was thought, would have a wholesome effect upon the temper of the Americans.

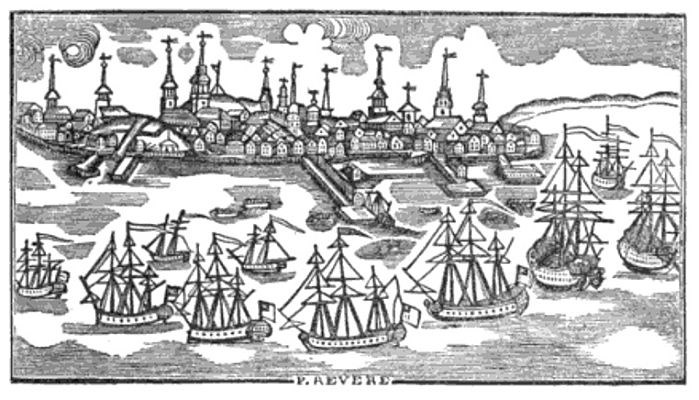

LANDING OF THE TROOPS IN BOSTON, 1768

CASTLE WILLIAM, BOSTON HARBOUR

It was now, in the summer of 1768, that Samuel Adams made up his mind that there was no hope of redress from the British government, and that the only remedy was to be found in the assertion of political independence by the American colonies.

Samuel Adams makes up his mind, 1768The courteous petitions and temperate remonstrances of the American assemblies had been met, not by rational arguments, but by insulting and illegal royal orders; and now at last an army was on the way from England to enforce the tyrannical measures of government, and to terrify the people into submission. Accordingly, Adams came to the conclusion that the only proper course for the colonies was to declare themselves independent of Great Britain, to unite together in a permanent confederation, and to invite European alliances. We have his own word for the fact that from this moment until the Declaration of Independence, in 1776, he consecrated all his energies, with burning enthusiasm, upon the attainment of that great object. Yet in 1768 no one knew better than Samuel Adams that the time had not yet come when his bold policy could be safely adopted, and that any premature attempt at armed resistance on the part of Massachusetts might prove fatal. At this time, probably no other American statesman had thought the matter out so far as to reach Adams’s conclusions. No American had as yet felt any desire to terminate the political connection with England. Even those who most thoroughly condemned the measures of the government did not consider the case hopeless, but believed that in one way or another a peaceful solution was still attainable. For a long time this attitude was sincerely and patiently maintained. Even Washington, when he came to take command of the army at Cambridge, after the battle of Bunker Hill, had not made up his mind that the object of the war was to be the independence of the colonies. In the same month of July, 1775, Jefferson said expressly, “We have not raised armies with designs of separating from Great Britain and establishing independent states. Necessity has not yet driven us into that desperate measure.” The Declaration of Independence was at last brought about only with difficulty and after prolonged discussion. Our great-great-grandfathers looked upon themselves as Englishmen, and felt proud of their connection with England. Their determination to resist arbitrary measures was at first in no way associated in their minds with disaffection toward the mother-country. Besides this, the task of effecting a separation by military measures seemed to most persons quite hopeless. It was not until after Bunker Hill had shown that American soldiers were a match for British soldiers in the field, and after Washington’s capture of Boston had shown that the enemy really could be dislodged from a whole section of the country, that the more hopeful patriots began to feel confident of the ultimate success of a war for independence. It is hard for us now to realize how terrible the difficulties seemed to the men who surmounted them. Throughout the war, beside the Tories who openly sympathized with the enemy, there were many worthy people who thought we were “going too far,” and who magnified our losses and depreciated our gains, – quite like the people who, in the War of Secession, used to be called “croakers.” The depression of even the boldest, after such defeats as that of Long Island, was dreadful. How inadequate was the general sense of our real strength, how dim the general comprehension of the great events that were happening, may best be seen in the satirical writings of some of the loyalists. At the time of the French alliance, there were many who predicted that the result of this step would be to undo the work of the Seven Years’ War, to reinstate the French in America with full control over the thirteen colonies, and to establish despotism and popery all over the continent. A satirical pamphlet, published in 1779, just ten years before the Bastille was torn down in Paris, drew an imaginary picture of a Bastille which ten years later was to stand in New York, and, with still further license of fantasy, portrayed Samuel Adams in the garb of a Dominican friar. Such nonsense is of course no index to the sentiments or the beliefs of the patriotic American people, but the mere fact that it could occur to anybody shows how hard it was for people to realize how competent America was to take care of herself. The more we reflect upon the slowness with which the country came to the full consciousness of its power and importance, the more fully we bring ourselves to realize how unwilling America was to tear herself asunder from England, and how the Declaration of Independence was only at last resorted to when it had become evident that no other course was compatible with the preservation of our self-respect; the more thoroughly we realize all this, the nearer we shall come toward duly estimating the fact that in 1768, seven years before the battle of Lexington, the master mind of Samuel Adams had fully grasped the conception of a confederation of American states independent of British control. The clearness with which he saw this, as the inevitable outcome of the political conditions of the time, gave to his views and his acts, in every emergency that arose, a commanding influence throughout the land.

In September, 1768, it was announced in Boston that the troops were on their way, and would soon be landed. There happened to be a legal obstacle, unforeseen by the ministry, to their being quartered in the town. In accordance with the general act of Parliament for quartering troops, the regular barracks at Castle William in the harbour would have to be filled before the town could be required to find quarters for any troops. Another clause of the act provided that if any military officer should take upon himself to quarter soldiers in any of his Majesty’s dominions otherwise than as allowed by the act, he should be straightway dismissed the service.

Arrival of troops in BostonAt the news that the troops were about to arrive, the governor was asked to convene the assembly, that it might be decided how to receive them. On Bernard’s refusal, the selectmen of Boston issued a circular, inviting all the towns of Massachusetts to send delegates to a general convention, in order that deliberate action might be taken upon this important matter. In answer to the circular, delegates from ninety-six towns assembled in Faneuil Hall, and, laughing at the governor’s order to “disperse,” proceeded to show how, in the exercise of the undoubted right of public meeting, the colony could virtually legislate for itself, in the absence of its regular legislature. The convention, finding that nothing was necessary for Boston to do but insist upon strict compliance with the letter of the law, adjourned. In October, two regiments arrived, and were allowed to land without opposition, but no lodging was provided for them. Bernard, in fear of an affray, had gone out into the country; but nothing could have been farther from the thoughts of the people. The commander, Colonel Dalrymple, requested shelter for his men, but was told that he must quarter them in the barracks at Castle William. As the night was frosty, however, the Sons of Liberty allowed them to sleep in Faneuil Hall. Next day, the governor, finding everything quiet, came back, and heard Dalrymple’s complaint. But in vain did he apply in turn to the council, to the selectmen, and to the justices of the peace, to grant quarters for the troops; he was told that the law was plain, and that the Castle must first be occupied. The governor then tried to get possession of an old dilapidated building which belonged to the colony; but the tenants had taken legal advice, and told him to turn them out if he dared. Nothing could be more provoking. General Gage was obliged to come on from his headquarters at New York; but not even he, the commander-in-chief of his Majesty’s forces in America, could quarter the troops in violation of the statute without running the risk of being cashiered, on conviction before two justices of the peace. So the soldiers stayed at night in tents on the Common, until the weather grew so cold that Dalrymple was obliged to hire some buildings for them at exorbitant rates, and at the expense of the Crown. By way of insult to the people, two cannon were planted on King Street, with their muzzles pointing toward the Town House. But as the troops could do nothing without a requisition from a civil magistrate, and as the usual strict decorum was preserved throughout the town, there was nothing in the world for them to do. In case of an insurrection, the force was too small to be of any use; and so far as the policy of overawing the town was concerned, no doubt the soldiers were more afraid of the people than the people of the soldiers.

Letters of “Vindex”No sooner were the soldiers thus established in Boston than Samuel Adams published a series of letters signed “Vindex,” in which he argued that to keep up “a standing army within the kingdom in time of peace, without the consent of Parliament, was against the law; that the consent of Parliament necessarily implied the consent of the people, who were always present in Parliament, either by themselves or by their representatives; and that the Americans, as they were not and could not be represented in Parliament, were therefore suffering under military tyranny over which they were allowed to exercise no control.” The only notice taken of this argument by Bernard and Hillsborough was an attempt to collect evidence upon the strength of which its author might be indicted for treason, and sent over to London to be tried; but Adams had been so wary in all his proceedings that it was impossible to charge him with any technical offence, and to have seized him otherwise than by due process of law would have been to precipitate rebellion in Massachusetts.

GENERAL HENRY CONWAY

In Parliament, the proposal to extend the act of Henry VIII. to America was bitterly opposed by Burke, Barré, Pownall, and Dowdeswell, as well as by Grenville, who characterized it as sheer madness; but the measure was carried, nevertheless.

Debate in ParliamentBurke further maintained, in an eloquent speech, that the royal order requiring Massachusetts to rescind her circular letter was unconstitutional; and here again Grenville agreed with him. The attention of Parliament, during the spring of 1769, was occupied chiefly with American affairs. Pownall moved that the Townshend acts should be repealed, and in this he was earnestly seconded by a petition of the London merchants; for the non-importation policy of Americans had begun to bear hard upon business in London. After much debate, Lord North proposed a compromise, repealing all the Townshend acts except that which laid duty on tea. The more clear-headed members saw that such a compromise, which yielded nothing in the matter of principle, would do no good. Beckford pointed out the fact that the tea-duty did not bring in £300 to the government; and Lord Beauchamp pertinently asked whether it were worth while, for such a paltry revenue, to make enemies of three millions of people. Grafton, Camden, Conway, Burke, Barré, and Dowdeswell wished to have the tea-duty repealed also, and the whole principle of parliamentary taxation given up; and Lord North agreed with them in his secret heart, but could not bring himself to act contrary to the king’s wishes. “America must fear you before she can love you,” said Lord North… “I am against repealing the last act of Parliament, securing to us a revenue out of America; I will never think of repealing it until I see America prostrate at my feet.” “To effect this,” said Barré, “is not so easy as some imagine; the Americans are a numerous, a respectable, a hardy, a free people.

Colonel Barré’s speechBut were it ever so easy, does any friend to his country really wish to see America thus humbled? In such a situation, she would serve only as a monument of your arrogance and your folly. For my part, the America I wish to see is America increasing and prosperous, raising her head in graceful dignity, with freedom and firmness asserting her rights at your bar, vindicating her liberties, pleading her services, and conscious of her merit. This is the America that will have spirit to fight your battles, to sustain you when hard pushed by some prevailing foe, and by her industry will be able to consume your manufactures, support your trade, and pour wealth and splendour into your towns and cities. If we do not change our conduct towards her, America will be torn from our side… Unless you repeal this law, you run the risk of losing America.” But the ministers were deaf to Barré’s sweet reasonableness. “We shall grant nothing to the Americans,” said Lord Hillsborough, “except what they may ask with a halter round their necks.” “They are a race of convicted felons,” echoed poor old Dr. Johnson, – who had probably been reading Moll Flanders, – “and they ought to be thankful for anything we allow them short of hanging.”