полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

As the result of the discussion, Lord North’s so-called compromise was adopted, and a circular was sent to America, promising that all the obnoxious acts, except the tea duty, should be repealed. At the same time, Bernard was recalled from Massachusetts to appease the indignation of the people, and made a baronet to show that the ministry approved of his conduct as governor.

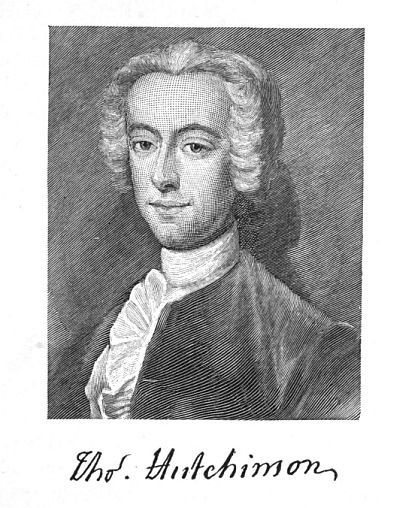

Thomas HutchinsonHis place was filled by the lieutenant-governor, Thomas Hutchinson, a man of great learning and brilliant talent, whose “History of Massachusetts Bay” entitles him to a high rank among the worthies of early American literature. The next year Hutchinson was appointed governor. As a native of Massachusetts, it was supposed by Lord North that he would be less likely to irritate the people than his somewhat arrogant predecessor. But in this the government turned out to be mistaken. As to Hutchinson’s sincere patriotism there can now be no doubt whatever. There was something pathetic in the intensity of his love for New England, which to him was the goodliest of all lands, the paradise of this world. He had been greatly admired for his learning and accomplishments, and the people of Massachusetts had elected him to one office after another, and shown him every mark of esteem until the evil days of the Stamp Act. It then began to appear that he was a Tory on principle, and a thorough believer in the British doctrine of the absolute supremacy of Parliament, and popular feeling presently turned against him. He was called a turncoat and traitor, and a thankless dog withal, whose ruling passion was avarice. His conduct and his motives were alike misjudged. He had tried to dissuade the Grenville ministry from passing the Stamp Act; but when once the obnoxious measure had become law, he thought it his duty to enforce it like other laws. For this he was charged with being recreant to his own convictions, and in the shameful riot of August, 1765, he was the worst sufferer. No public man in America has ever been the object of more virulent hatred. None has been more grossly misrepresented by historians. His appointment as governor, however well meant, turned out to be anything but a wise measure.

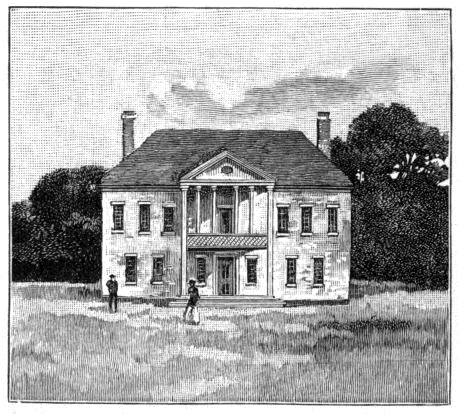

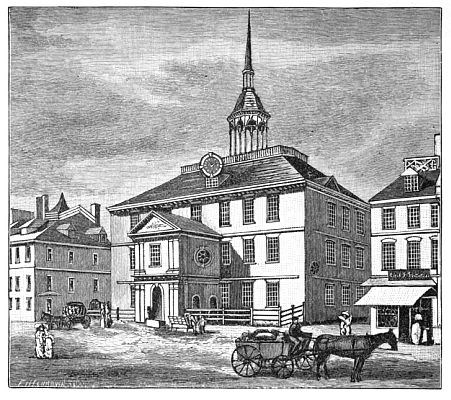

CAPITOL AT WILLIAMSBURGH, VIRGINIA

While these things were going on, a strong word of sympathy came from Virginia. When Hillsborough made up his mind to browbeat Boston, he thought it worth while to cajole the Virginians, and try to win them from the cause which Massachusetts was so boldly defending. So Lord Botetourt, a genial and conciliatory man, was sent over to be governor of Virginia, to beguile the people with his affable manner and sweet discourse. But between a quarrelsome Bernard and a gracious Botetourt the practical difference was little, where grave questions of constitutional right were involved.

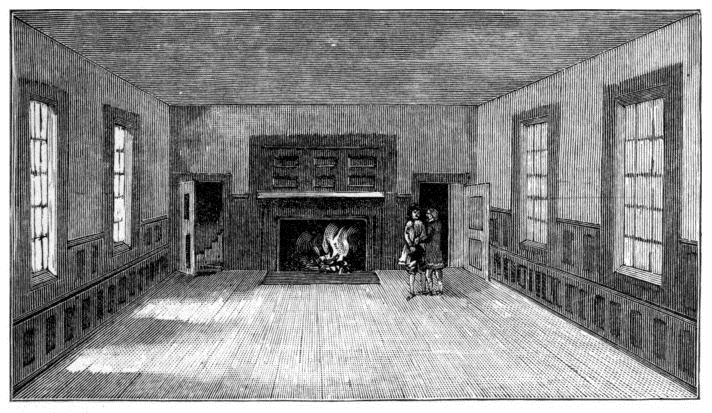

STOVE USED IN THE HOUSE OF BURGESSES

Virginia resolutions, 1769

In May, 1769, the House of Burgesses assembled at Williamsburgh. Among its members were Patrick Henry, Washington, and Jefferson. The assembly condemned the Townshend acts, asserted that the people of Virginia could be taxed only by their own representatives, declared that it was both lawful and expedient for all the colonies to join in a protest against any violation of the rights of Americans, and especially warned the king of the dangers that might ensue if any American citizen were to be carried beyond sea for trial. Finally, it sent copies of these resolutions to all the other colonial assemblies, inviting their concurrence. At this point Lord Botetourt dissolved the assembly; but the members straightway met again in convention at the famous Apollo room of the Raleigh tavern, and adopted a series of resolutions prepared by Washington, in which they pledged themselves to continue the policy of non-importation until all the obnoxious acts of 1767 should be repealed. These resolutions were adopted by all the southern colonies.

APOLLO ROOM IN THE RALEIGH TAVERN

All through the year 1769, the British troops remained quartered in Boston at the king’s expense. According to Samuel Adams, their principal employment seemed to be to parade in the streets, and by their merry-andrew tricks to excite the contempt of women and children. But the soldiers did much to annoy the people, to whom their very presence was an insult. They led brawling, riotous lives, and made the quiet streets hideous by night with their drunken shouts. Scores of loose women, who had followed the regiments across the ocean, came to scandalize the town for a while, and then to encumber the almshouse. On Sundays the soldiers would race horses on the Common, or play Yankee Doodle just outside the church-doors during the services. Now and then oaths, or fisticuffs, or blows with sticks, were exchanged between soldiers and citizens, and once or twice a more serious affair occurred.

Assault on James OtisOne evening in September, a dastardly assault was made upon James Otis, in the British Coffee House, by one Robinson, a commissioner of customs, assisted by half a dozen army officers. It reminds one of the assault upon Charles Sumner by Brooks of South Carolina, shortly before the War of Secession. Otis was savagely beaten, and received a blow on the head with a sword, from the effects of which he never recovered, but finally lost his reason. The popular wrath at this outrage was intense, but there was no disturbance. Otis brought suit against Robinson, and recovered £2,000 in damages, but refused to accept a penny of it when Robinson confessed himself in the wrong, and humbly asked pardon for his irreparable offence.

OLD BRICK MEETING-HOUSE

On the 22d of February, 1770, an informer named Richardson, being pelted by a party of schoolboys, withdrew into his house, opened a window, and fired at random into the crowd, killing one little boy and severely wounding another. He was found guilty of murder, but was pardoned. At last, on the 2d of March, an angry quarrel occurred between a party of soldiers and some of the workmen at a ropewalk, and for two or three days there was considerable excitement in the town, and people talked together, standing about the streets in groups; but Hutchinson did not even take the precaution of ordering the soldiers to be kept within their barracks, for he did not believe that the people intended a riot, nor that the troops would dare to fire on the citizens without express permission from himself. On the evening of March 5th, at about eight o’clock, a large crowd collected near the barracks, on Brattle Street, and from bandying abusive epithets with the soldiers began pelting them with snow-balls and striking at them with sticks, while the soldiers now and then dealt blows with their muskets.

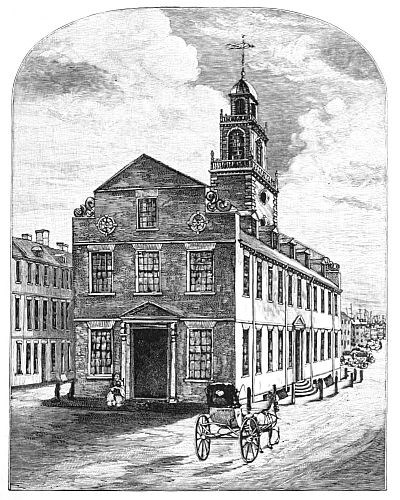

The “Boston Massacre”Presently Captain Goldfinch, coming along, ordered the men into their barracks for the night, and thus stopped the affray. But meanwhile some one had got into the Old Brick Meeting-House, opposite the head of King Street, and rung the bell; and this, being interpreted as an alarm of fire, brought out many people into the moonlit streets. It was now a little past nine. The sentinel who was pacing in front of the Custom House had a few minutes before knocked down a barber’s boy for calling names at the captain, as he went up to stop the affray on Brattle Street. The crowd in King Street now began to pelt the sentinel, and some shouted, “Kill him!” when Captain Preston and seven privates from the twenty-ninth regiment crossed the street to his aid: and thus the file of nine soldiers confronted an angry crowd of fifty or sixty unarmed men, who pressed up to the very muzzles of their guns, threw snow at their faces, and dared them to fire. All at once, but quite unexpectedly and probably without orders from Preston, seven of the levelled pieces were discharged, instantly killing four men and wounding seven others, of whom two afterwards died. Immediately the alarm was spread through the town, and it might have gone hard with the soldiery, had not Hutchinson presently arrived on the scene, and quieted the people by ordering the arrest of Preston and his men. Next morning the council advised the removal of one of the regiments, but in the afternoon an immense town meeting, called at Faneuil Hall, adjourned to the Old South Meeting-House; and as they passed by the Town House (or what we now call the Old State House), the lieutenant-governor, looking out upon their march, judged “their spirit to be as high as was the spirit of their ancestors when they imprisoned Andros, while they were four times as numerous.” All the way from the church to the Town House the street was crowded with the people, while a committee, headed by Samuel Adams, waited upon the governor, and received his assurance that one regiment should be removed. As the committee came out from the Town House, to carry the governor’s reply to the meeting in the church, the people pressed back on either side to let them pass; and Adams, leading the way with uncovered head through the lane thus formed, and bowing first to one side and then to the other, passed along the watchword, “Both regiments, or none!” When, in the church, the question was put to vote, three thousand voices shouted, “Both regiments, or none!” and armed with this ultimatum the committee returned to the Town House, where the governor was seated with Colonel Dalrymple and the members of the council. Then Adams, in quiet but earnest tones, stretching forth his arm and pointing his finger at Hutchinson, said that if as acting governor of the province he had the power to remove one regiment he had equally the power to remove both, that the voice of three thousand freemen demanded that all soldiery be forthwith removed from the town, and that if he failed to heed their just demand, he did so at his peril. “I observed his knees to tremble,” said the old hero afterward, “I saw his face grow pale, – and I enjoyed the sight!” That Hutchinson was agitated we may well believe; not from fear, but from a sudden sickening sense of the odium of his position as king’s representative at such a moment. He was a man of invincible courage, and surely would never have yielded to Adams, had he not known that the law was on the side of the people and that the soldiers were illegal trespassers in Boston. Before sundown the order had gone forth for the removal of both regiments to Castle William, and not until then did the meeting in the church break up. From that day forth the fourteenth and twenty-ninth regiments were known in Parliament as “the Sam Adams regiments.”

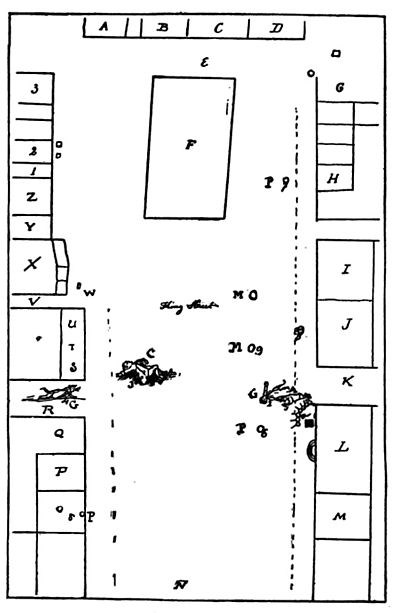

PAUL REVERE’S PLAN OF KING STREET IN 1770

(Used in the trial of the soldiers)

OLD STATE HOUSE, WEST FRONT

Such was the famous Boston Massacre. All the mildness of New England civilization is brought most strikingly before us in that truculent phrase. The careless shooting of half a dozen townsmen is described by a word which historians apply to such events as Cawnpore or the Sicilian Vespers. Lord Sherbrooke, better known as Robert Lowe, declared a few years ago, in a speech on the uses of a classical education, that the battle of Marathon was really of less account than a modern colliery explosion, because only one hundred and ninety-two of the Greek army lost their lives! From such a point of view, one might argue that the Boston Massacre was an event of far less importance than an ordinary free fight among Colorado gamblers. It is needless to say that this is not the historical point of view. Historical events are not to be measured with a foot-rule.

Some lessons of the “Massacre”This story of the Boston Massacre is a very trite one, but it has its lessons. It furnishes an instructive illustration of the high state of civilization reached by the people among whom it happened, – by the oppressors as well as those whom it was sought to oppress. The quartering of troops in a peaceful town is something that has in most ages been regarded with horror. Under the senatorial government of Rome, it used to be said that the quartering of troops, even upon a friendly province and for the purpose of protecting it, was a visitation only less to be dreaded than an inroad of hostile barbarians. When we reflect that the British regiments were encamped in Boston during seventeen months, among a population to whom they were thoroughly odious, the fact that only half a dozen persons lost their lives, while otherwise no really grave crimes seem to have been committed, is a fact quite as creditable to the discipline of the soldiers as to the moderation of the people. In most ages and countries, the shooting of half a dozen citizens under such circumstances would either have produced but a slight impression, or, on the other hand, would perhaps have resulted on the spot in a wholesale slaughter of the offending soldiers. The fact that so profound an impression was made in Boston and throughout the country, while at the same time the guilty parties were left to be dealt with in the ordinary course of law, is a striking commentary upon the general peacefulness and decorum of American life, and it shows how high and severe was the standard by which our forefathers judged all lawless proceedings. And here it may not be irrelevant to add that, throughout the constitutional struggles which led to the Revolution, the American standard of political right and wrong was so high that contemporary European politicians found it sometimes difficult to understand it. And for a like reason, even the most fair-minded English historians sometimes fail to see why the Americans should have been so quick to take offence at acts of the British government which doubtless were not meant to be oppressive. If George III. had been a bloodthirsty despot, like Philip II. of Spain; if General Gage had been another Duke of Alva; if American citizens by the hundred had been burned alive or broken on the wheel in New York and Boston; if whole towns had been given up to the cruelty and lust of a beastly soldiery, then no one – not even Dr. Johnson – would have found it hard to understand why the Americans should have exhibited a rebellious temper. But it is one signal characteristic of the progress of political civilization that the part played by sheer brute force in a barbarous age is fully equalled by the part played by a mere covert threat of injustice in a more advanced age. The effect which a blow in the face would produce upon a barbarian will be wrought upon a civilized man by an assertion of some far-reaching legal principle, which only in a subtle and ultimate analysis includes the possibility of a blow in the face. From this point of view, the quickness with which such acts as those of Charles Townshend were comprehended in their remotest bearings is the must striking proof one could wish of the high grade of political culture which our forefathers had reached through their system of perpetual free discussion in town meeting. They had, moreover, reached a point where any manifestation of brute force in the course of a political dispute was exceedingly disgusting and shocking to them. To their minds, the careless slaughter of six citizens conveyed as much meaning as a St. Bartholomew massacre would have conveyed to the minds of men in a lower stage of political development. It was not strange, therefore, that Samuel Adams and his friends should have been ready to make the Boston Massacre the occasion of a moral lesson to their contemporaries. As far as the poor soldiers were concerned, the most significant fact is that there was no attempt to wreak a paltry vengeance on them. Brought to trial on a charge of murder, after a judicious delay of seven months, they were ably defended by John Adams and Josiah Quincy, and all were acquitted save two, who were convicted of manslaughter, and let off with slight punishment. There were some hotheads who grumbled at the verdict, but the people of Boston generally acquiesced in it, as they showed by immediately choosing John Adams for their representative in the assembly – a fact which Mr. Lecky calls very remarkable. Such an event as the Boston Massacre could not fail for a long time to point a moral among a people so unused to violence and bloodshed. One of the earliest of American engravers, Paul Revere, published a quaint coloured engraving of the scene in King Street, which for a long time was widely circulated, though it has now become very scarce. At the same time, it was decided that the fatal Fifth of March should be solemnly commemorated each year by an oration to be delivered in the Old South Meeting-House; and this custom was kept up until the recognition of American independence in 1783, when the day for the oration was changed to the Fourth of July.

Lord North’s ministryFive weeks before the Boston Massacre the Duke of Grafton had resigned, and Lord North had become prime minister of England. The colonies were kept under , and that great friend of arbitrary government, Lord Thurlow, as solicitor-general, became the king’s chief legal adviser. George III was now, to all intents and purposes, his own prime minister, and remained so until after the overthrow at Yorktown. The colonial policy of the government soon became more vexatious than ever. The promised repeal of all the Townshend acts, except the act imposing the tea-duty, was carried through Parliament in April, and its first effect in America, as Lord North had foreseen, was to weaken the spirit of opposition, and to divide the more complaisant colonies from those that were most staunch. The policy of non-importation had pressed with special severity upon the commerce of New York, and the merchants there complained that the fire-eating planters of Virginia and farmers of Massachusetts were growing rich at the expense of their neighbours.

The merchants of New YorkIn July, the New York merchants broke the non-importation agreement, and sent orders to England for all sorts of merchandise except tea. Such a measure, on the part of so great a seaport, virtually overthrew the non-importation policy, upon which the patriots mainly relied to force the repeal of the Tea Act. The wrath of the other colonies was intense. At the Boston town meeting the letter of the New York merchants was torn in pieces. In New Jersey, the students of Princeton College, James Madison being one of the number, assembled on the green in their black gowns and solemnly burned the letter, while the church-bells were tolled. The offending merchants were stigmatized as “Revolters,” and in Charleston their conduct was vehemently denounced. “You had better send us your old liberty-pole,” said Philadelphia to New York, with bitter sarcasm, “for you clearly have no further use for it.”

This breaking of the non-importation agreement by New York left no general issue upon which the colonies could be sure to unite unless the ministry should proceed to force an issue upon the Tea Act. For the present, Lord North saw the advantage he had gained, and was not inclined to take any such step. Nevertheless, as just observed, the policy of the government soon became more vexatious than ever.

Assemblies convened at strange placesIn the summer of 1770, the king entered upon a series of local quarrels with the different colonies, taking care not to raise any general issue. Royal instructions were sent over to the different governments, enjoining courses of action which were unconstitutional and sure to offend the people. The assemblies were either dissolved, or convened at strange places, as at Beaufort in South Carolina, more than seventy miles from the capital, or at Cambridge in Massachusetts. The local governments were as far as possible ignored, and local officers were appointed, with salaries to be paid by the Crown. In Massachusetts, these officers were illegally exempted from the payment of taxes.

Taxes in MarylandIn Maryland, where the charter had expressly provided that no taxes could ever be levied by the British Crown, the governor was ordered to levy taxes indirectly by reviving a law regulating officers’ fees, which had expired by lapse of time.

The North Carolina “Regulators”In North Carolina, excessive fees were extorted, and the sheriffs in many cases collected taxes of which they rendered no account. The upper counties of both the Carolinas were peopled by a hardy set of small farmers and herdsmen, Presbyterians, of Scotch-Irish pedigree, who were known by the name of “Regulators,” because, under the exigencies of their rough frontier life, they formed voluntary associations for the regulation of their own police and the condign punishment of horse-thieves and other criminals.

In 1771, the North Carolina Regulators, goaded by repeated acts of extortion and of unlawful imprisonment, rose in rebellion. A battle was fought at Alamance, near the headwaters of the Cape Fear river, in which the Regulators were totally defeated by Governor Tryon, leaving more than a hundred of their number dead and wounded upon the field: and six of their leaders, taken prisoners, were summarily hanged for treason. After this achievement Tryon was promoted to the governorship of New York, where he left his name for a time upon the vaguely defined wilderness beyond Schenectady, known in the literature of the Revolutionary War as Tryon County.

In Rhode Island, the eight-gun schooner Gaspee, commanded by Lieutenant Duddington, was commissioned to enforce the revenue acts along the coasts of Narragansett Bay, and she set about the work with reckless and indiscriminating zeal. “Thorough” was Duddington’s motto, as it was Lord Stafford’s. He not only stopped and searched every vessel that entered the bay, and seized whatever goods he pleased, whether there was any evidence of their being contraband or not, but, besides this, he stole the sheep and hogs of the farmers near the coast, cut down their trees, fired upon market-boats, and behaved in general with unbearable insolence. In March, 1772, the people of Rhode Island complained of these outrages. The matter was referred to Rear-Admiral Montagu, commanding the little fleet in Boston harbour. Montagu declared that the lieutenant was only doing his duty, and threatened the Rhode Island people in case they should presume to interfere. For three months longer the Gaspee kept up her irritating behaviour, until one evening in June, while chasing a swift American ship, she ran aground. The following night she was attacked by a party of men in eight boats, and captured after a short skirmish, in which Duddington was severely wounded. The crew was set on shore, and the schooner was burned to the water’s edge. This act of reprisal was not relished by the government, and large rewards were offered for the arrest of the men concerned in it; but although probably everybody knew who they were, it was impossible to obtain any evidence against them. By a royal order in council, the Rhode Island government was commanded to arrest the offenders and deliver them to Rear-Admiral Montagu, to be taken over to England for trial; but Stephen Hopkins, the venerable chief justice of Rhode Island, flatly refused to take cognizance of any such arrest if made within the colony.

The black thunder clouds of war now gathered quickly. In August, 1772, the king ventured upon an act which went further than anything that had yet occurred toward hastening on the crisis.

The salaries of the judgesIt was ordered that all the Massachusetts judges, holding their places during the king’s pleasure, should henceforth have their salaries paid by the Crown, and not by the colony. This act, which aimed directly at the independence of the judiciary, aroused intense indignation. The people of Massachusetts were furious, and Samuel Adams now took a step which contributed more than anything that had yet been done toward organizing the opposition to the king throughout the whole country. The idea of establishing committees of correspondence was not wholly new.