полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

On receiving these instructions from the Congress, the people of Massachusetts at once proceeded to organize a provisional government in accordance with the spirit of the Suffolk resolves. Gage had issued a writ convening the assembly at Salem for the 1st of October, but before the day arrived he changed his mind, and prorogued it. In disregard of this order, however, the representatives met at Salem a week later, organized themselves into a provincial congress, with John Hancock for president, and adjourned to Concord.

Provincial Congress in MassachusettsOn the 27th they chose a committee of safety, with Warren for chairman, and charged it with the duty of collecting military stores. In December this Congress dissolved itself, but a new one assembled at Cambridge on the 1st of February, and proceeded to organize the militia and appoint general officers. A special portion of the militia, known as “minute men,” were set apart, under orders to be ready to assemble at a moment’s warning; and the committee of safety were directed to call out this guard as soon as Gage should venture to enforce the Regulating Act. Under these instructions every village green in Massachusetts at once became the scene of active drill. Nor was it a population unused to arms that thus began to marshal itself into companies and regiments. During the French war one fifth of all the able-bodied men of Massachusetts had been in the field, and in 1757 the proportion had risen to one third. There were plenty of men who had learned how to stand under fire, and officers who had held command on hard-fought fields; and all were practised marksmen. It is quite incorrect to suppose that the men who first repulsed the British regulars in 1775 were a band of farmers, utterly unused to fighting. Their little army was indeed a militia, but it was made up of warlike material.

CARPENTERS’ HALL, PHILADELPHIA

Meeting of the Continental Congress, Sept. 5, 1774

While these preparations were going on in Massachusetts, the Continental Congress had assembled at the Hall of the Company of Carpenters, in Philadelphia, on the 5th of September. Peyton Randolph, of Virginia, was chosen president; and the Adamses, the Livingstons, the Rutledges, Dickinson, Chase, Pendleton, Lee, Henry, and Washington took part in the debates. One of their first acts was to dispatch Paul Revere to Boston with their formal approval of the action of the Suffolk Convention. After four weeks of deliberation they agreed upon a declaration of rights, claiming for the American people “a free and exclusive power of legislation in their provincial legislatures, where their rights of legislation could alone be preserved in all cases of taxation and internal polity." This paper also specified the rights of which they would not suffer themselves to be deprived, and called for the repeal of eleven acts of Parliament by which these rights had been infringed. Besides this, they formed an association for insuring commercial non-intercourse with Great Britain, and charged the committees of correspondence with the duty of inspecting the entries at all custom houses. Addresses were also prepared, to be sent to the king, to the people of Great Britain, and to the inhabitants of British America. The 10th of May was appointed for a second Congress, in which the Canadian colonies and the Floridas were invited to join; and on the 26th of October the Congress dissolved itself.

The ability of the papers prepared by the first Continental Congress has long been fully admitted in England as well as in America. Chatham declared them unsurpassed by any state papers ever composed in any age or country. But the king’s manipulation of rotten boroughs in the election of November, 1774, was only too successful, and the new Parliament was not in the mood for listening to reason. Chatham, Shelburne, and Camden urged in vain that the vindictive measures of the last April should be repealed and the troops withdrawn from Boston. On the 1st of February, Chatham introduced a bill which, could it have passed, would no doubt have averted war, even at the eleventh hour.

Debates in ParliamentBesides repealing its vindictive measures, Parliament was to renounce forever the right of taxing the colonies, while retaining the right of regulating the commerce of the whole empire; and the Americans were to defray the expenses of their own governments by taxes voted in their colonial assemblies. A few weeks later, in the House of Commons, Burke argued that the abstract right of Parliament to tax the colonies was not worth contending for, and he urged that on large grounds of expediency it should be abandoned, and that the vindictive acts should be repealed. But both Houses, by large majorities, refused to adopt any measures of conciliation, and in a solemn joint address to the king declared themselves ready to support him to the end in the policy upon which he had entered. Massachusetts was declared to be in a state of rebellion, and acts were passed closing all the ports of New England, and prohibiting its fishermen from access to the Newfoundland fisheries. At the same time it was voted to increase the army at Boston to 10,000 men, and to supersede Gage, who had in all these months accomplished so little with his four regiments. As people in England had utterly failed to comprehend the magnitude of the task assigned to Gage, it was not strange that they should seek to account for his inaction by doubting his zeal and ability. No less a person than David Hume saw fit to speak of him as a “lukewarm coward.” William Howe, member of Parliament for the liberal constituency of Nottingham, was chosen to supersede him. In his speeches as candidate for election only four months ago, Howe had declared himself opposed to the king’s policy, had asserted that no army that England could raise would be able to subdue the Americans, and, in reply to a question, had promised that if offered a command in America he would refuse it. When he now consented to take Gage’s place as commander-in-chief, the people of Nottingham scolded him roundly for breaking his word.

It would be unfair, however, to charge Howe with conscious breach of faith in this matter. His appointment was itself a curious symptom of the element of vacillation that was apparent in the whole conduct of the ministry, even when its attitude professed to be most obstinate and determined. With all his obstinacy the king did not really wish for war, – much less did Lord North; and the reason for Howe’s appointment was simply that he was a brother to the Lord Howe who had fallen at Ticonderoga, and whose memory was idolized by the men of New England. Lord North announced that, in dealing with his misguided American brethren, his policy would be always to send the olive branch in company with the sword; and no doubt Howe really felt that, by accepting a command offered in such a spirit, he might more efficiently serve the interests of humanity and justice than by leaving it open for some one of cruel and despotic temper, whose zeal might outrun even the wishes of the obdurate king.

Richard, Lord HoweAt the same time, his brother Richard, Lord Howe, a seaman of great ability, was appointed admiral of the fleet for America, and was expressly entrusted with the power of offering terms to the colonies. Sir Henry Clinton and John Burgoyne, both of them in sympathy with the king’s policy, were appointed to accompany Howe as lieutenant-generals.

The conduct of the ministry, during this most critical and trying time, showed great uneasiness. When leave was asked for Franklin to present the case for the Continental Congress, and to defend it before the House of Commons, it was refused. Yet all through the winter the ministry were continually appealing to Franklin, unofficially and in private, in order to find out how the Americans might be appeased without making any such concessions as would hurt the pride of that Tory party which was now misgoverning England. Lord Howe was the most conspicuous agent in these fruitless negotiations. How to conciliate the Americans without giving up a single one of the false positions which the king had taken was the problem, and no wonder that Franklin soon perceived it to be insolvable, and made up his mind to go home.

Franklin returns to AmericaHe had now stayed in England for several years, as agent for Pennsylvania and for Massachusetts. He had shown himself a consummate diplomatist, of that rare school which deceives by telling unwelcome truths, and he had some unpleasant encounters with the king and the king’s friends. Now in March, 1775, seeing clearly that he could be of no further use in averting an armed struggle, he returned to America. Franklin’s return was not, in form, like that customary withdrawal of an ambassador which heralds and proclaims a state of war. But practically it was the snapping of the last diplomatic link between the colonies and the mother-country.

Still the ministry, with all its uneasiness, did not believe that war was close at hand. It was thought that the middle colonies, and especially New York, might be persuaded to support the government, and that New England, thus isolated, would not venture upon armed resistance to the overwhelming power of Great Britain. The hope was not wholly unreasonable; for the great middle colonies, though conspicuous for material prosperity, were somewhat lacking in force of political ideas. In New York and Pennsylvania the non-English population was relatively far more considerable than in Virginia or the New England colonies. A considerable proportion of the population had come from the continent of Europe, and the principles of constitutional government were not so thoroughly inwrought into the innermost minds and hearts of the people, the pulse of liberty did not beat so quickly here, as in the purely English commonwealths of Virginia and Massachusetts.

The middle coloniesIn Pennsylvania and New Jersey the Quakers were naturally opposed to a course of action that must end in war; and such very honourable motives certainly contributed to weaken the resistance of these colonies to the measures of the government. In New York there were further special reasons for the existence of a strong loyalist feeling. The city of New York had for many years been the headquarters of the army and the seat of the principal royal government in America. It was not a town, like Boston, governing itself in town meeting, but its municipal affairs were administered by a mayor, appointed by the king. Unlike Boston and Philadelphia, the interests of the city of New York were almost purely commercial, and there was nothing to prevent the little court circle there from giving the tone to public opinion. The Episcopal Church, too, was in the ascendant, and there was a not unreasonable prejudice against the Puritans of New England for their grim intolerance of Episcopalians and their alleged antipathy to Dutchmen. The province of New York, moreover, had a standing dispute with its eastern neighbours over the ownership of the Green Mountain region. This beautiful country had been settled by New England men, under grants from the royal governors of New Hampshire; but it was claimed by the people of New York, and the controversy sometimes waxed hot and gave rise to very hard feelings.

Lord North’s mistaken hopes of securing New YorkUnder these circumstances, the labours of the ministry to secure this central colony seemed at times likely to be crowned with success. The assembly of New York refused to adopt the non-importation policy enjoined by the Continental Congress, and it refused to choose delegates to the second Congress which was to be held in May. The ministry, in return, sought to corrupt New York by exempting it from the commercial restrictions placed upon the neighbouring colonies, and by promising to confirm its alleged title to the territory of Vermont. All these hopes proved fallacious, however. In spite of appearances, the majority of the people of New York were opposed to the king’s measures, and needed only an opportunity for organization. In April, under the powerful leadership of Philip Schuyler and the Livingstons, a convention was held, delegates were chosen to attend the Congress, and New York fell into line with the other colonies. As for Pennsylvania, in spite of its peaceful and moderate temper, it had never shown any signs of willingness to detach itself from the nascent union.

News travelled with slow pace in those days, and as late as the middle of May, Lord North, confident of the success of his schemes in New York, and unable to believe that the yeomanry of Massachusetts would fight against regular troops, declared cheerfully that this American business was not so alarming as it seemed, and everything would no doubt be speedily settled without bloodshed!

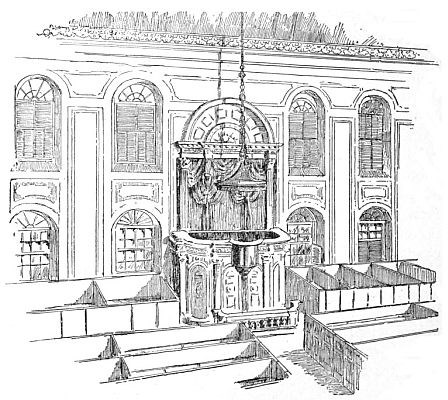

INTERIOR OF OLD SOUTH MEETING-HOUSE

Affairs in Massachusetts

Great events had meanwhile happened in Massachusetts. All through the winter the resistance to General Gage had been passive, for the lesson had been thoroughly impressed upon the mind of every man, woman, and child in the province that, in order to make sure of the entire sympathy of the other colonies, Great Britain must be allowed to fire the first shot. The Regulating Act had none the less been silently defied, and neither councillors nor judges, neither sheriffs nor jurymen, could be found to serve under the royal commission. It is striking proof of the high state of civilization attained by this commonwealth, that although for nine months the ordinary functions of government had been suspended, yet the affairs of every-day life had gone on without friction or disturbance Not a drop of blood had been shed, nor had any one’s property been injured. The companies of yeomen meeting at eventide to drill on the village green, and now and then the cart laden with powder and ball that dragged slowly over the steep roads on its way to Concord, were the only outward signs of an unwonted state of things. Not so, however, in Boston. There the blockade of the harbour had wrought great hardship for the poorer people. Business was seriously interfered with, many persons were thrown out of employment, and in spite of the generous promptness with which provisions had been poured in from all parts of the country, there was great suffering through scarcity of fuel and food. Still there was but little complaint and no disorder. The leaders were as resolute as ever, and the people were as resolute as their leaders. As the 5th of March drew near, several British officers were heard to declare that any one who should dare to address the people in the Old South Church on this occasion would surely lose his life.

Warren’s oration at the Old SouthAs soon as he heard of these threats, Joseph Warren solicited for himself the dangerous honour, and at the usual hour delivered a stirring oration upon “the baleful influence of standing armies in time of peace.” The concourse in the church was so great that when the orator arrived every approach to the pulpit was blocked up; and rather than elbow his way through the crowd, which might lead to some disturbance, he procured a ladder, and climbed in through a large window at the back of the pulpit. About forty British officers were present, some of whom sat on the pulpit steps, and sought to annoy the speaker with groans and hisses, but everything passed off quietly.

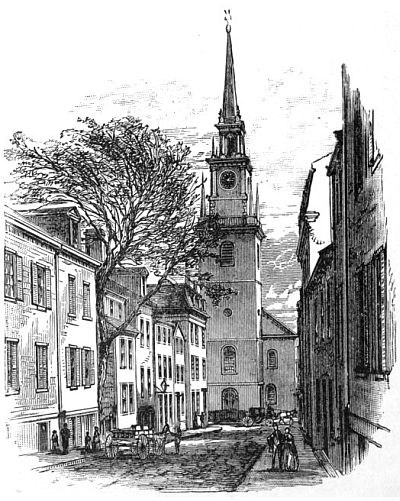

OLD NORTH CHURCH, IN WHICH SIGNAL WAS HUNG

Attempt to corrupt Samuel Adams

The boldness of Adams and Hancock in attending this meeting was hardly less admirable than that of Warren in delivering the address. It was no secret that Gage had been instructed to watch his opportunity to arrest Samuel Adams and “his willing and ready tool,” that “terrible desperado,” John Hancock, and send them over to England to be tried for treason. Here was an excellent opportunity for seizing all the patriot leaders at once; and the meeting itself, moreover, was a town meeting, such as Gage had come to Boston expressly to put down. Nothing more calmly defiant can be imagined than the conduct of people and leaders under these circumstances. But Gage had long since learned the temper of the people so well that he was afraid to proceed too violently. At first he had tried to corrupt Samuel Adams with offers of place or pelf; but he found, as Hutchinson had already declared, that such was “the obstinate and inflexible disposition of this man that he never would be conciliated by any office or gift whatsoever.” The dissolution of the assembly, of which Adams was clerk, had put a stop to his salary, and he had so little property laid by as hardly to be able to buy bread for his family. Under these circumstances, it occurred to Gage that perhaps a judicious mixture of threat with persuasion might prove effectual. So he sent Colonel Fenton with a confidential message to Adams. The officer, with great politeness, began by saying that “an adjustment of the existing disputes was very desirable; that he was authorized by Governor Gage to assure him that he had been empowered to confer upon him such benefits as would be satisfactory, upon the condition that he would engage to cease in his opposition to the measures of government, and that it was the advice of Governor Gage to him not to incur the further displeasure of his Majesty; that his conduct had been such as made him liable to the penalties of an act of Henry VIII., by which persons could be sent to England for trial, and, by changing his course, he would not only receive great personal advantages, but would thereby make his peace with the king.” Adams listened with apparent interest to this recital until the messenger had concluded. Then rising, he replied, glowing with indignation: “Sir, I trust I have long since made my peace with the King of kings. No personal consideration shall induce me to abandon the righteous cause of my country. Tell Governor Gage it is the advice of Samuel Adams to him no longer to insult the feelings of an exasperated people.”

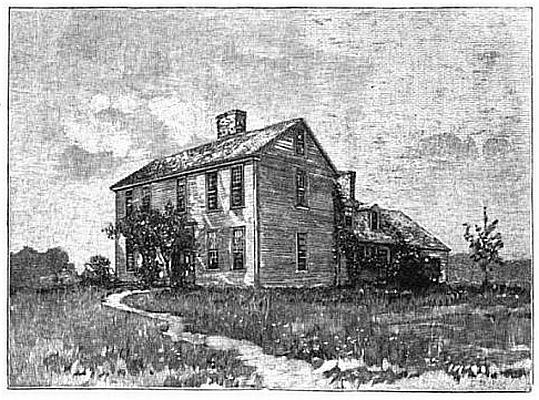

REV. JONAS CLARK’S HOUSE

Orders to arrest Adams and Hancock

Toward the end of the winter Gage received peremptory orders to arrest Adams and Hancock, and send them to England for trial. One of the London papers gayly observed that in all probability Temple Bar “will soon be decorated with some of the patriotic noddles of the Boston saints.” The provincial congress met at Concord on the 22d of March, and after its adjournment, on the 15th of April, Adams and Hancock stayed a few days at Lexington, at the house of their friend, the Rev. Jonas Clark.

It would doubtless be easier to seize them there than in Boston, and, accordingly, on the night of the 18th Gage dispatched a force of 800 troops, under Lieutenant-Colonel Francis Smith, to march to Lexington, and, after seizing the patriot leaders, to proceed to Concord, and capture or destroy the military stores which had for some time been collecting there. At ten in the evening the troops were rowed across Charles river, and proceeded by a difficult and unfrequented route through the marshes of East Cambridge, until, after four miles, they struck into the highroad for Lexington. The greatest possible secrecy was observed, and stringent orders were given that no one should be allowed to leave Boston that night.

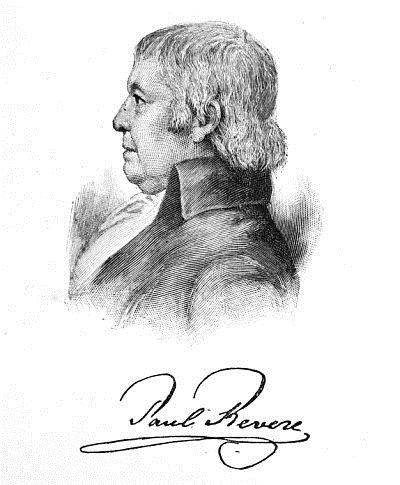

Paul Revere’s rideBut Warren divined the purpose of the movement, and sent out Paul Revere by way of Charlestown, and William Dawes by way of Roxbury, to give the alarm. At that time there was no bridge across Charles river lower than the one which now connects Cambridge with Allston. Crossing the broad river in a little boat, under the very guns of the Somerset man-of-war, and waiting on the farther bank until he learned, from a lantern suspended in the belfry of the North Church, which way the troops had gone, Revere took horse and galloped over the Medford road to Lexington, shouting the news at the door of every house that he passed. Reaching Mr. Clark’s a little after midnight, he found the house guarded by eight minute-men, and the sergeant warned him not to make a noise and disturb the inmates. “Noise!” cried Revere. “You’ll soon have noise enough; the regulars are coming!” Hancock, recognizing the voice, threw up the window, and ordered the guard to let him in. On learning the news, Hancock’s first impulse was to stay and take command of the militia; but it was presently agreed that there was no good reason for his doing so, and shortly before daybreak, in company with Adams, he left the village.

JONATHAN HARRINGTON’S HOUSE

Meanwhile, the troops were marching along the main road; but swift and silent as was their advance, frequent alarm-bells and signal-guns, and lights twinkling on distant hilltops, showed but too plainly that the secret was out. Colonel Smith then sent Major Pitcairn forward with six companies of light infantry to make all possible haste in securing the bridges over Concord river, while at the same time he prudently sent back to Boston for reinforcements.

When Pitcairn reached Lexington, just as the rising sun was casting long shadows across the village green, he found himself confronted by some fifty minute-men under command of Captain John Parker, – grandfather of Theodore Parker, – a hardy veteran, who, fifteen years before, had climbed the heights of Abraham by the side of Wolfe.

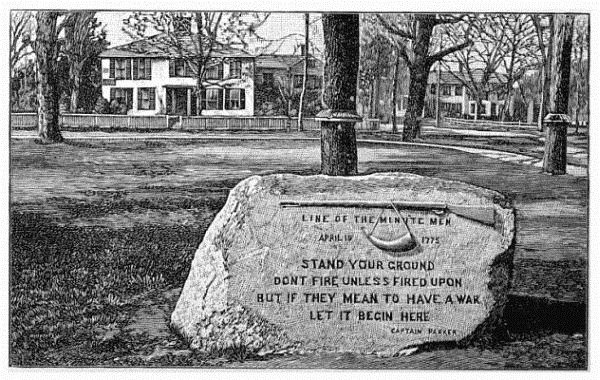

Pitcairn fires upon the yeomanry, April 19, 1775“Stand your ground,” said Parker. “Don’t fire unless fired upon; but if they mean to have a war, let it begin here.” “Disperse, ye villains!” shouted Pitcairn. “Damn you, why don’t you disperse?” And as they stood motionless he gave the order to fire.

THE MINUTE-MAN[3]

As the soldiers hesitated to obey, he discharged his own pistol and repeated the order, whereupon a deadly volley slew eight of the minute-men and wounded ten. One of the victims, Jonathan Harrington, was just able to stagger across the green to his own house (which is still there), and to die in the arms of his wife, who was standing at the door. At this moment the head of Smith’s own column seems to have come into sight, far down the road. The minute-men had begun to return the fire, when Parker, seeing the folly of resistance, ordered them to retire. While this was going on, Adams and Hancock were walking across the fields toward Woburn; and as the crackle of distant musketry reached their ears, the eager Adams – his soul aglow with the prophecy of the coming deliverance of his country – exclaimed, “Oh, what a glorious morning is this!” From Woburn the two friends went on their way to Philadelphia, where the second Continental Congress was about to assemble.

THE OLD MANSE AT CONCORD

Some precious minutes had been lost by the British at Lexington, and it soon became clear that the day was to be one in which minutes could ill be spared. By the time they reached Concord, about seven o’clock, the greater part of the stores had been effectually hidden, and minute-men were rapidly gathering from all quarters. After posting small forces to guard the bridges, the troops set fire to the court-house, cut down the liberty-pole, disabled a few cannon, staved in a few barrels of flour, and hunted unsuccessfully for arms and ammunition, until an unexpected incident put a stop to their proceedings.