полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

From Richmond toward Fredericksburg – over the ground made doubly famous by the movements of Lee and Grant – the youthful general kept up his retreat, never giving the eager earl a chance to deal him a blow; for, as with naïve humour he wrote to Washington, “I am not strong enough even to be beaten.” On the 4th of June Lafayette crossed the Rapidan at Ely’s Ford and placed himself in a secure position; while Cornwallis, refraining from the pursuit, sent Tarleton on a raid westward to Charlottesville, to break up the legislature, which was in session there, and to capture the governor, Thomas Jefferson. The raid, though conducted with Tarleton’s usual vigour, failed of its principal prey; for Jefferson, forewarned in the nick of time, got off to the mountains about twenty minutes before the cavalry surrounded his house at Monticello. It remained for Tarleton to seize the military stores collected at Albemarle; but on the 10th of June Lafayette effected a junction with 1,000 Pennsylvania regulars under Wayne, and thereupon succeeded in placing his whole force between Tarleton and the prize he was striving to reach. Unable to break through this barrier, Tarleton had nothing left him but to rejoin Cornwallis; and as Lafayette’s army was reinforced from various sources until it amounted to more than 4,000 men, he became capable of annoying the earl in such wise as to make him think it worth while to get nearer to the sea. Cornwallis, turning southwestward from the North Anna river, had proceeded as far inland as Point of Forks when Tarleton joined him. On the 15th of June, the British commander, finding that he could not catch “the boy,” and was accomplishing nothing by his marches and countermarches in the interior, retreated down the James river to Richmond.

Cornwallis retreats to the coastIn so doing he did not yet put himself upon the defensive. Lafayette was still too weak to risk a battle, or to prevent his going wherever he liked. But Cornwallis was too prudent a general to remain at a long distance from his base of operations, among a people whom he had found, to his great disappointment, thoroughly hostile. By retreating to the seaboard, he could make sure of supplies and reinforcements, and might presently resume the work of invasion. Accordingly, on the 20th he continued his retreat from Richmond, crossing the Chickahominy a little above White Oak Swamp, and marching down the York peninsula as far as Williamsburg. Lafayette, having been further reinforced by Steuben, so that his army numbered more than 5,000, pressed closely on the rear of the British all the way down the peninsula; and on the 6th of July an action was fought between parts of the two armies, at Green Spring, near Williamsburg, in which the Americans were repulsed with a loss of 145 men.[42]

and occupies YorktownThe campaign was ended by the first week in August, when Cornwallis occupied Yorktown, adding the garrison of Portsmouth to his army, so that it numbered 7,000 men, while Lafayette planted himself on Malvern Hill, and awaited further developments. Throughout this game of strategy, Lafayette had shown commendable skill, proving himself a worthy antagonist for the ablest of the British generals. But a far greater commander than either the Frenchman or the Englishman was now to enter most unexpectedly upon the scene. The elements of the catastrophe were prepared, and it only remained for a master hand to strike the blow.

Elements of the final catastrophe; arrival of the French fleetAs early as the 22d of May, just two days before the beginning of this Virginia campaign, Washington had held a conference with Rochambeau, at Wethersfield, in Connecticut, and it was there decided that a combined attack should be made upon New York by the French and American armies. If they should succeed in taking the city, it would ruin the British cause; and, at all events, it was hoped that if New York was seriously threatened Sir Henry Clinton would take reinforcements from Cornwallis, and thus relieve the pressure upon the southern states. In order to undertake the capture of New York, it would be necessary to have the aid of a powerful French fleet; and the time had at last arrived when such assistance was confidently to be expected. The naval war between France and England in the West Indies had now raged for two years, with varying fortunes. The French government had exerted itself to the utmost, and early in the spring of this year had sent out a magnificent fleet of twenty-eight ships-of-the-line and six frigates, carrying 1,700 guns and 20,000 men, commanded by Count de Grasse, one of the ablest of the French admirals. It was designed to take from England the great island of Jamaica; but as the need for naval coöperation upon the North American coast had been strongly urged upon the French ministry, Grasse was ordered to communicate with Washington and Rochambeau, and to seize the earliest opportunity of acting in concert with them.

The arrival of this fleet would introduce a feature into the war such as had not existed at any time since hostilities had begun. It would interrupt the British control over the water. The utmost force the British were ready to oppose to it amounted only to nineteen ships-of-the-line, carrying 1,400 guns and 13,000 men, and this disparity was too great to be surmounted by anything short of the genius of a Nelson. The conditions of the struggle were thus about to be suddenly and decisively altered. The retreat of Cornwallis upon Yorktown had been based entirely upon the assumption of that British naval supremacy which had hitherto been uninterrupted. The safety of his position depended wholly upon the ability of the British fleet to control the Virginia waters. Once let the French get the upper hand there, and the earl, if assailed in front by an overwhelming land force, would be literally “between the devil and the deep sea.” He would be no better off than Burgoyne in the forests of northern New York.

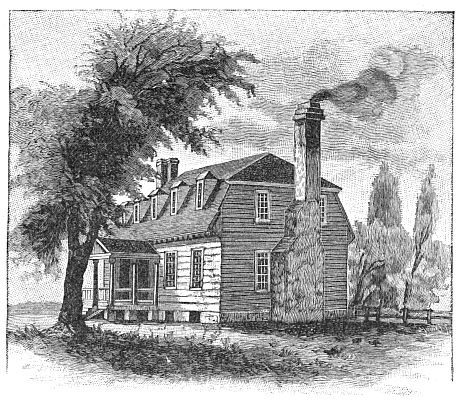

CORNWALLIS’S HEADQUARTERS AT YORKTOWN

News from Grasse and Lafayette

It was not yet certain, however, where Grasse would find it best to strike the coast. The elements of the situation disclosed themselves but slowly, and it required the master mind of Washington to combine them. Intelligence travelled at snail’s pace in those days, and operations so vast in extent were not within the compass of anything but the highest military genius. It took ten days for Washington to hear from Lafayette, and it took a month for him to hear from Greene, while there was no telling just when definite information would arrive from Grasse. But so soon as Washington heard from Greene, in April, how he had manœuvred Cornwallis up into Virginia, he began secretly to consider the possibility of leaving a small force to guard the Hudson, while taking the bulk of his army southward to overwhelm Cornwallis. At the Wethersfield conference, he spoke of this to Rochambeau, but to no one else; and a dispatch to Grasse gave him the choice of sailing either for the Hudson or for Chesapeake bay. So matters stood till the middle of August, while Washington, grasping all the elements of the problem, vigilantly watched the whole field, holding himself in readiness for either alternative, – to strike New York close at hand, or to hurl his army to a distance of four hundred miles. On the 14th of August a message came from Grasse that he was just starting from the West Indies for Chesapeake bay, with his whole fleet, and hoped that whatever the armies had to do might be done quickly, as he should be obliged to return to the West Indies by the middle of October. Washington could now couple with this the information, just received from Lafayette, that Cornwallis had established himself at Yorktown, where he had deep water on three sides of him, and a narrow neck in front.

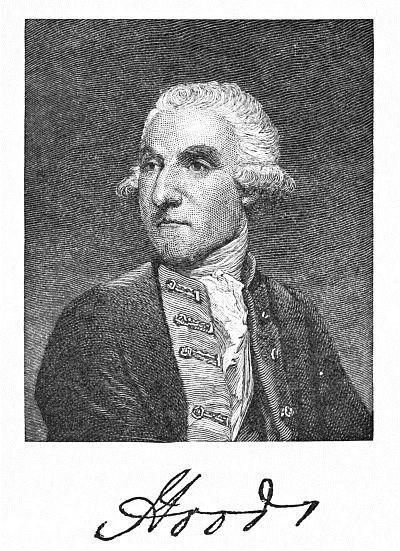

WASHINGTON SILHOUETTE BY FOLWELL

Subtle and audacious scheme of Washington

The supreme moment of Washington’s military career had come, – the moment for realizing a conception which had nothing of a Fabian character about it, for it was a conception of the same order as those in which Cæsar and Napoleon dealt. He decided at once to transfer his army to Virginia and overwhelm Cornwallis. He had everything in readiness. The army of Rochambeau had marched through Connecticut, and joined him on the Hudson in July. He could afford to leave West Point with a comparatively small force, for that strong fortress could be taken only by a regular siege, and he had planned his march so as to blind Sir Henry Clinton completely. This was one of the finest points in Washington’s scheme, in which the perfection of the details matched the audacious grandeur of the whole. Sir Henry was profoundly unconscious of any such movement as Washington was about to execute; but he was anxiously looking out for an attack upon New York. Now, from the American headquarters near West Point, Washington could take his army more than half way through New Jersey without arousing any suspicion at all; for the enemy would be sure to interpret such a movement as preliminary to an occupation of Staten Island, as a point from which to assail New York. Sir Henry knew that the French fleet might be expected at any moment; but he had not the clue which Washington held, and his anxious thoughts were concerned with New York harbour, not with Chesapeake Bay. Besides all this, the sheer audacity of the movement served still further to conceal its true meaning. It would take some time for the enemy to comprehend so huge a sweep as that from New York to Virginia, and doubtless Washington could reach Philadelphia before his purpose could be fathomed.

He transfers his army to Virginia, Aug. 19-Sept. 18The events justified his foresight. On the 19th of August, five days after receiving the dispatch from Grasse, Washington’s army crossed the Hudson at King’s Ferry, and began its march. Lord Stirling was left with a small force at Saratoga, and General Heath, with 4,000 men, remained at West Point. Washington took with him southward 2,00 °Continentals and 4,000 Frenchmen. It was the only time during the war that French and American land forces marched together, save on the occasion of the disastrous attack upon Savannah. None save Washington and Rochambeau knew whither they were going. So precious was the secret that even the general officers supposed, until New Brunswick was passed, that their destination was Staten Island. So rapid was the movement that, however much the men might have begun to wonder, they had reached Philadelphia before the purpose of the expedition was distinctly understood.

As the army marched through the streets of Philadelphia, there was an outburst of exulting hope. The plan could no longer be hidden. Congress was informed of it, and a fresh light shone upon the people, already elated by the news of Greene’s career of triumph. The windows were thronged with fair ladies, who threw sweet flowers on the dusty soldiers as they passed, while the welkin rang with shouts, anticipating the great deliverance that was so soon to come. The column of soldiers, in the loose order adapted to its rapid march, was nearly two miles in length. First came the war-worn Americans, clad in rough toggery, which eloquently told the story of the meagre resources of a country without a government. Then followed the gallant Frenchmen, clothed in gorgeous trappings, such as could be provided by a government which at that time took three fourths of the earnings of its people in unrighteous taxation. There was some parading of these soldiers before the president of Congress, but time was precious. Washington, in his eagerness galloping on to Chester, received and sent back the joyful intelligence that Grasse had arrived in Chesapeake bay, and then the glee of the people knew no bounds. Bands of music played in the streets, every house hoisted its stars-and-stripes, and all the roadside taverns shouted success to the bold general. “Long live Washington!” was the toast of the day. “He has gone to catch Cornwallis in his mousetrap!”

But these things did not stop for a moment the swift advance of the army. It was on the 1st of September that they left Trenton behind them, and by the 5th they had reached the head of Chesapeake bay, whence they were conveyed in ships, and reached the scene of action, near Yorktown, by the 18th.

Movements of the fleetsMeanwhile, all things had been working together most auspiciously. On the 31st of August the great French squadron had arrived on the scene, and the only Englishman capable of defeating it, under the existing odds, was far away. Admiral Rodney’s fleet had followed close upon its heels from the West Indies, but Rodney himself was not in command. He had been taken ill suddenly, and had sailed for England, and Sir Samuel Hood commanded the fleet. Hood outsailed Grasse, passed him on the ocean without knowing it, looked in at the Chesapeake on the 25th of August, and, finding no enemy there, sailed on to New York to get instructions from Admiral Graves, who commanded the naval force in the North, This was the first that Graves or Clinton knew of the threatened danger. Not a moment was to be lost. The winds were favourable, and Graves, now chief in command, crowded sail for the Chesapeake, and arrived on the 5th of September, the very day on which Washington’s army was embarking at the head of the great bay. Graves found the French fleet blocking the entrance to the bay, and instantly attacked it. A decisive naval victory for the British would at this moment have ruined everything. But after a sharp fight of two hours’ duration, in which some 700 men were killed and wounded on the two fleets, Admiral Graves withdrew.

Three of his ships were badly damaged, and after manœuvering for four days he returned, baffled and despondent, to New York, leaving Grasse in full possession of the Virginia waters. The toils were thus fast closing around Lord Cornwallis. He knew nothing as yet of Washington’s approach, but there was just a chance that he might realize his danger, and, crossing the James river, seek safety in a retreat upon North Carolina. Lafayette forestalled this solitary chance. Immediately upon the arrival of the French squadron, the troops of the Marquis de Saint-Simon, 3,000 in number, had been set on shore and added to Lafayette’s army; and with this increased force, now amounting to more than 8,000 men, “the boy” came down on the 7th of September, and took his stand across the neck of the peninsula at Williamsburg, cutting off Cornwallis’s retreat.

MARQUIS DE LAFAYETTE

Cornwallis surrounded at Yorktown

Thus, on the morning of the 8th, the very day on which Greene, in South Carolina, was fighting his last battle at Eutaw Springs, Lord Cornwallis, in Virginia, found himself surrounded. The door of the mousetrap was shut. Still, but for the arrival of Washington, the plan would probably have failed. It was still in Cornwallis’s power to burst the door open. His force was nearly equal to Lafayette’s in numbers, and better in quality, for Lafayette’s contained 3,000 militia. Cornwallis carefully reconnoitred the American lines, and seriously thought of breaking through; but the risk was considerable, and heavy loss was inevitable. He had not the slightest inkling of Washington’s movements, and he believed that Graves would soon return with force enough to drive away Grasse’s blockading squadron. So he decided to wait before striking a hazardous blow. It was losing his last chance. On the 14th Washington reached Lafayette’s headquarters, and took command. On the 18th the northern army began arriving in detachments, and by the 26th it was all concentrated at Williamsburg, more than 16,000 strong. The problem was solved. The surrender of Cornwallis was only a question of time. It was the great military surprise of the Revolutionary War. Had any one predicted, eight months before, that Washington on the Hudson and Cornwallis on the Catawba, eight hundred miles apart, would so soon come together and terminate the war on the coast of Virginia, he would have been thought a wild prophet indeed. For thoroughness of elaboration and promptness of execution, the movement, on Washington’s part, was as remarkable as the march of Napoleon in the autumn of 1805, when he swooped from the shore of the English Channel into Bavaria, and captured the Austrian army at Ulm.

Clinton’s attempt at a counterstrokeBy the 2d of September, Sir Henry Clinton, learning that the American army had reached the Delaware, and coupling with this the information he had got from Admiral Hood, began to suspect the true nature of Washington’s movement, and was at his wit’s end. The only thing he could think of was to make a counterstroke on the coast of Connecticut, and he accordingly detached Benedict Arnold with 2,000 men to attack New London.

Arnold’s proceedings at New London, Sept. 6It was the boast of this sturdy little state that no hostile force had ever slept a night upon her soil. Such blows as her coast towns had received had been dealt by an enemy who retreated as quickly as he had come; and such was again to be the case. The approach to New London was guarded by two forts on opposite banks of the river Thames, but Arnold’s force soon swept up the west bank, bearing down all opposition and capturing the city. In Fort Griswold, on the east bank, 157 militia were gathered and made a desperate resistance. The fort was attacked by 600 regulars, and after losing 192 men, or 35 more than the entire number of the garrison, they carried it by storm. No quarter was given, and of the little garrison only 26 escaped unhurt.[43] The town of New London was laid in ashes; minute-men came swarming by hundreds; the enemy reëmbarked before sunset and returned up the Sound. And thus, on the 6th of September, 1781, with this wanton assault upon the peaceful neighbourhood where the earliest years of his life had been spent, the brilliant and wicked Benedict Arnold disappears from American history.[44]

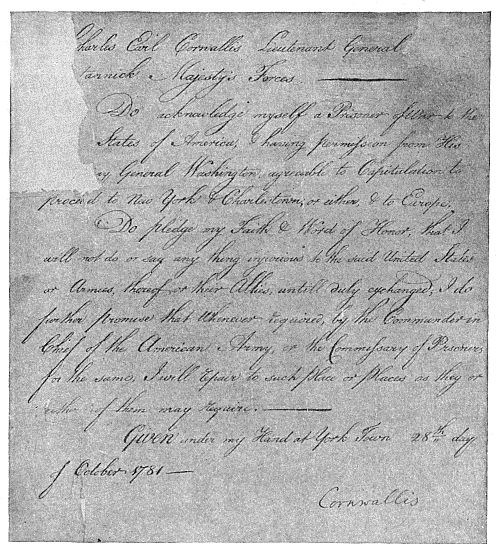

Surrender of Cornwallis, Oct. 19, 1781A thoroughly wanton assault it was, for it did not and could not produce the slightest effect upon the movements of Washington. By the time the news of it had reached Virginia, the combination against Cornwallis had been completed, and day by day the lines were drawn more closely about the doomed army. Yorktown was invested, and on the 6th of October the first parallel was opened by General Lincoln. On the 11th, the second parallel, within three hundred yards of the enemy’s works, was opened by Steuben. On the night of the 14th Alexander Hamilton and the Baron de Viomenil carried two of the British redoubts by storm. On the next night the British made a gallant but fruitless sortie. By noon of the 16th their works were fast crumbling to pieces under the fire of seventy cannon. On the 17th – the fourth anniversary of Burgoyne’s surrender – Cornwallis hoisted the white flag. The terms of the surrender were like those of Lincoln’s at Charleston. The British army became prisoners of war, subject to the ordinary rules of exchange. The only delicate question related to the American loyalists in the army, whom Cornwallis felt it wrong to leave in the lurch. This point was neatly disposed of by allowing him to send a ship to Sir Henry Clinton, with news of the catastrophe, and to embark in it such troops as he might think proper to send to New York, and no questions asked. On a little matter of etiquette the Americans were more exacting. The practice of playing the enemy’s tunes had always been cherished as an inalienable prerogative of British soldiery; and at the surrender of Charleston, in token of humiliation, General Lincoln’s army had been expressly forbidden to play any but an American tune. Colonel Laurens, who now conducted the negotiations, directed that Lord Cornwallis’s sword should be received by General Lincoln, and that the army, on marching out to lay down its arms, should play a British or a German air. There was no help for it; and on the 19th of October, Cornwallis’s army, 7,247 in number, with 840 seamen, marched out with colours furled and cased, while the band played a quaint old English melody, of which the significant title was “The World Turned Upside Down!”

MOORE’S HOUSE, YORKTOWN, IN WHICH THE TERMS OF SURRENDER WERE ARRANGED

Importance of the aid rendered by the French fleet and army

On the very same day that Cornwallis surrendered, Sir Henry Clinton, having received naval reinforcements, sailed from New York with twenty-five ships-of-the-line and ten frigates, and 7,000 of his best troops. Five days brought him to the mouth of the Chesapeake, where he learned that he was too late, as had been the case four years before, when he tried to relieve Burgoyne. A fortnight earlier, this force might perhaps have seriously altered the result, for the fleet was strong enough to dispute with Grasse the control over the coast. The French have always taken to themselves the credit of the victory of Yorktown. In the palace of Versailles there is a room the walls of which are covered with huge paintings depicting the innumerable victories of France, from the days of Chlodwig to those of Napoleon. Near the end of the long series, the American visitor cannot fail to notice a scene which is labelled “Bataille de Yorcktown” (misspelled, as is the Frenchman’s wont in dealing with the words of outer barbarians), in which General Rochambeau occupies the most commanding position, while General Washington is perforce contented with a subordinate place. This is not correct history, for the glory of conceiving and conducting the movement undoubtedly belongs to Washington. But it should never be forgotten, not only that the 4,000 men of Rochambeau and the 3,000 of Saint-Simon were necessary for the successful execution of the plan, but also that without the formidable fleet of Grasse the plan could not even have been made. How much longer the war might have dragged out its tedious length, or what might have been its final issue, without this timely assistance, can never be known; and our debt of gratitude to France for her aid on this supreme occasion is something which should always be duly acknowledged.[45]

PAROLE OF CORNWALLIS

Effect of the news in England

Early on a dark morning of the fourth week in October, an honest old German, slowly pacing the streets of Philadelphia on his night watch, began shouting, “Basht dree o’glock, und Gornvallis ish dakendt!” and light sleepers sprang out of bed and threw up their windows. Washington’s courier laid the dispatches before Congress in the forenoon, and after dinner a service of prayer and thanksgiving was held in the Lutheran Church. At New Haven and Cambridge the students sang triumphal hymns, and every village green in the country was ablaze with bonfires. The Duke de Lauzun sailed for France in a swift ship, and on the 27th of November all the houses in Paris were illuminated, and the aisles of Notre Dame resounded with the Te Deum. At noon of November 25th, the news was brought to Lord George Germain, at his house in Pall Mall. Getting into a cab, he drove hastily to the Lord Chancellor’s house in Great Russell Street, Bloomsbury, and took him in; and then they drove to Lord North’s office in Downing Street. At the staggering news, all the Prime Minister’s wonted gayety forsook him. He walked wildly up and down the room, throwing his arms about and crying, “O God! it is all over! it is all over! it is all over!” A dispatch was sent to the king at Kew, and when Lord George received the answer that evening, at dinner, he observed that his Majesty wrote calmly, but had forgotten to date his letter, – a thing which had never happened before.

“The tidings,” says Wraxall, who narrates these incidents, “were calculated to diffuse a gloom over the most convivial society, and opened a wide field for political speculation.” There were many people in England, however, who looked at the matter differently from Lord North. This crushing defeat was just what the Duke of Richmond, at the beginning of the war, had publicly declared he hoped for. Charles Fox always took especial delight in reading about the defeats of invading armies, from Marathon and Salamis downward; and over the news of Cornwallis’s surrender he leaped from his chair and clapped his hands. In a debate in Parliament, four months before, the youthful William Pitt had denounced the American war as “most accursed, wicked, barbarous, cruel, unnatural, unjust, and diabolical,” which led Burke to observe, “He is not a chip of the old block; he is the old block itself!”