полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

LORD CORNWALLIS

and again severs the British line at Princeton, Jan. 3

Just at this critical moment Washington came galloping upon the field and rallied the troops, and as the entire forces on both sides had now come up the fight became general. In a few minutes the British were routed and their line was cut in two; one half fleeing toward Trenton, the other half toward New Brunswick. There was little slaughter, as the whole fight did not occupy more than twenty minutes. The British lost about 200 in killed and wounded, with 300 prisoners and their cannon; the American loss was less than 100.

Shortly before sunrise, the men who had been left in the camp on the Assunpink to feed the fires and make a noise beat a hasty retreat, and found their way to Princeton by circuitous paths. When Cornwallis got up, he could hardly believe his eyes. Here was nothing before him but an empty camp: the American army had vanished, and whither it had gone he could not imagine. But his perplexity was soon relieved by the booming of distant cannon on the Princeton road, and the game which the “old fox” had played him all at once became apparent.

General retreat of the British toward New YorkNothing was to be done but to retreat upon New Brunswick with all possible haste, and save the stores there. His road led back through Princeton, and from Mawhood’s fugitives he soon heard the story of the morning’s disaster. His march was hindered by various impediments. A thaw had set in, so that the little streams had swelled into roaring torrents, difficult to ford, and the American army, which had passed over the road before daybreak, had not forgotten to destroy the bridges. By the time that Cornwallis and his men reached Princeton, wet and weary, the Americans had already left it, but they had not gone on to New Brunswick. Washington had hoped to seize the stores there, but the distance was eighteen miles, his men were wretchedly shod and too tired to march rapidly, and it would not be prudent to risk a general engagement when his main purpose could be secured without one. For these reasons, Washington turned northward to the heights of Morristown, while Cornwallis continued his retreat to New Brunswick. A few days later, Putnam advanced from Philadelphia and occupied Princeton, thus forming the right wing of the American army, of which the main body lay at Morristown, while Heath’s division on the Hudson constituted the left wing. Various cantonments were established along this long line. On the 5th, George Clinton, coming down from Peekskill, drove the British out of Hackensack and occupied it, while on the same day a detachment of German mercenaries at Springfield was routed by a body of militia. Elizabethtown was then taken by General Maxwell, whereupon the British retired from Newark.

Thus in a brief campaign of three weeks Washington had rallied the fragments of a defeated and broken army, fought two successful battles, taken nearly 2,000 prisoners, and recovered the state of New Jersey. He had cancelled the disastrous effects of Lee’s treachery, and replaced things apparently in the condition in which the fall of Fort Washington had left them.

The tables completely turnedReally he had done much more than this, for by assuming the offensive and winning victories through sheer force of genius, he had completely turned the tide of popular feeling. The British generals began to be afraid of him, while on the other hand his army began to grow by the accession of fresh recruits. In New Jersey, the enemy retained nothing but New Brunswick, Amboy, and Paulus Hook.

On the 25th of January Washington issued a proclamation declaring that all persons who had accepted Lord Howe’s offer of protection must either retire within the British lines or come forward and take the oath of allegiance to the United States. Many narrow-minded people, who did not look with favour upon a close federation of the states, commented severely upon the form of this proclamation: it was too national, they said. But it proved effective. However lukewarm may have been the interest which many of the Jersey people felt in the war when their soil was first invaded, the conduct of the British troops had been such that every one now looked upon them as enemies. They had foraged indiscriminately upon friend and foe; they had set fire to farmhouses, and in one or two instances murdered peaceful citizens. The wrath of the people had waxed so hot that it was not safe for the British to stir beyond their narrow lines except in considerable force. Their foraging parties were waylaid and cut off by bands of yeomanry, and so sorely were they harassed in their advanced position at New Brunswick that they often suffered from want of food. Many of the German mercenaries, caring nothing for the cause in which they had been forcibly enlisted, began deserting; and in this they were encouraged by Congress, which issued a manifesto in German, making a liberal offer of land to any foreign soldier who should leave the British service. This little document was inclosed in the wrappers in which packages of tobacco were sold, and every now and then some canny smoker accepted the offer.

Washington’s superb generalshipWashington’s position at Morristown was so strong that there was no hope of dislodging him, and the snow-blocked roads made the difficulties of a winter campaign so great that Howe thought best to wait for warm weather before doing anything more. While the British arms were thus held in check, the friends of America, both in England and on the continent of Europe, were greatly encouraged. From this moment Washington was regarded in Europe as a first-rate general. Military critics who were capable of understanding his movements compared his brilliant achievements with his slender resources, and discovered in him genius of a high order. Men began to call him “the American Fabius;” and this epithet was so pleasing to his fellow-countrymen, in that pedantic age, that it clung to him for the rest of his life, and was repeated in newspapers and speeches and pamphlets with wearisome iteration. Yet there was something more than Fabian in Washington’s generalship. For wariness he has never been surpassed; yet, as Colonel Stedman observed, in his excellent contemporary history of the war, the most remarkable thing about Washington was his courage. It would be hard indeed to find more striking examples of audacity than he exhibited at Trenton and Princeton. Lord Cornwallis was no mean antagonist, and no one was a better judge of what a commander might be expected to do with a given stock of resources. His surprise at the Assunpink was so great that he never got over it. After the surrender at Yorktown, it is said that his lordship expressed to Washington his generous admiration for the wonderful skill which had suddenly hurled an army four hundred miles, from the Hudson river to the James, with such precision and such deadly effect. “But after all,” he added, “your excellency’s achievements in New Jersey were such that nothing could surpass them.” The man who had turned the tables on him at the Assunpink he could well believe to be capable of anything.

In England the effect of the campaign was very serious. Not long before, Edmund Burke had despondingly remarked that an army which was always obliged to refuse battle could never expel the invaders; but now the case wore a different aspect. Sir William Howe had not so much to show for his red ribbon, after all. He had taken New York, and dealt many heavy blows with his overwhelming force, unexpectedly aided by foul play on the American side; but as for crushing Washington and ending the war, he seemed farther from it than ever. It would take another campaign to do this, – perhaps many. Lord North, who had little heart for the war at any time, was discouraged, while the king and Lord George Germain were furious with disappointment. “It was that unhappy affair of Trenton,” observed the latter, “that blasted our hopes.”

In France the interest in American affairs grew rapidly. Louis XVI. had no love for Americans or for rebels, but revenge for the awful disasters of 1758 and 1759 was dear to the French heart. France felt toward England then as she feels toward Germany now, and so long ago as the time of the Stamp Act, Baron Kalb had been sent on a secret mission to America, to find out how the people regarded the British government. The policy of the French ministry was aided by the romantic sympathy for America which was felt in polite society. Never perhaps have the opinions current among fashionable ladies and gentlemen been so directly controlled by philosophers and scholars as in France during the latter half of the eighteenth century. Never perhaps have men of letters exercised such mighty influence over their contemporaries as Voltaire, with his noble enthusiasm for humanity, and Rousseau, with his startling political paradoxes, and the writers of the “Encyclopédie,” with their revelations of new points of view in science and in history. To such men as these, and to such profound political thinkers as Montesquieu and Turgot, the preservation of English liberty was the hope of the world; but they took little interest in the British crown or in the imperial supremacy of Parliament. All therefore sympathized with the Americans and urged on the policy which the court for selfish reasons was inclined to pursue. Vergennes, the astute minister of foreign affairs, had for some time been waiting for a convenient opportunity to take part in the struggle, but as yet he had contented himself with furnishing secret assistance.

For more than a year he had been intriguing, through Beaumarchais, the famous author of “Figaro,” with Arthur Lee (a brother of Richard Henry Lee), who had long served in London as agent for Virginia. Just before the Declaration of Independence Vergennes sent over a million dollars to aid the American cause. Soon afterwards Congress sent Silas Deane to Paris, and presently ordered Arthur Lee to join him there. In October Franklin was also sent over, and the three were appointed commissioners for making a treaty of alliance with France.

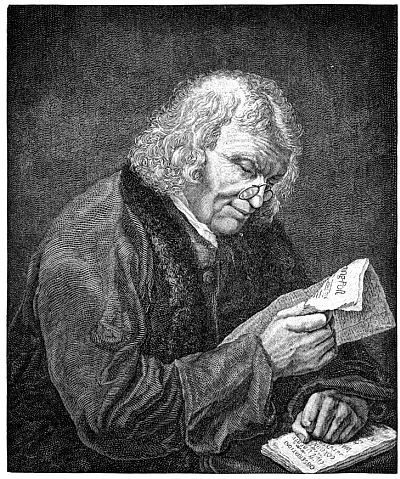

The arrival of Franklin was the occasion of great excitement in the fashionable world of Paris. By thinkers like Diderot and D’Alembert he was regarded as the embodiment of practical wisdom. To many he seemed to sum up in himself the excellences of the American cause, – justice, good sense, and moderation. Voltaire spoke quite unconsciously of the American army as “Franklin’s troops.” It was Turgot who said of him, in a line which is one of the finest modern specimens of epigrammatic Latin, “Eripuit cœlo fulmen, sceptrumque tyrannis.” As symbolizing the liberty for which all France was yearning, he was greeted with a popular enthusiasm such as perhaps no Frenchman except Voltaire has ever called forth. As he passed along the streets, the shopkeepers rushed to their doors to catch a glimpse of him, while curious idlers crowded the sidewalk. The charm of his majestic and venerable figure seemed heightened by the republican simplicity of his plain brown coat, over the shoulders of which his long gray hair fell carelessly, innocent of queue or powder. His portrait was hung in the shop-windows and painted in miniature on the covers of snuff-boxes. Gentlemen wore “Franklin” hats, ladies’ kid gloves were dyed of a “Franklin” hue, and cotelettes à la Franklin were served at fashionable dinners.

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

As the first fruits of Franklin’s negotiations, the French government agreed to furnish two million livres a year, in quarterly instalments, to assist the American cause. Three ships, laden with military stores, were sent over to America: one was captured by a British cruiser, but the other two arrived safely. The Americans were allowed to fit out privateers in French ports, and even to bring in and sell their prizes there. Besides this a million livres were advanced to the commissioners on account of a quantity of tobacco which they agreed to send in exchange. Further than this France was not yet ready to go. The British ambassador had already begun to protest against the violation of neutrality involved in the departure of privateers, and France was not willing to run the risk of open war with England until it should become clear that the Americans would prove efficient allies. The king, moreover, sympathized with George III., and hated the philosophers whose opinions swayed the French people; and in order to accomplish anything in behalf of the Americans he had to be coaxed or bullied at every step.

But though the French government was not yet ready to send troops to America, volunteers were not wanting who cast in their lot with us through a purely disinterested enthusiasm. At a dinner party in Metz, the Marquis de Lafayette, then a boy of nineteen, heard the news from America, and instantly resolved to leave his pleasant home and offer his services to Washington. He fitted up a ship at his own expense, loaded it with military stores furnished by Beaumarchais, and set sail from Bordeaux on the 26th of April, taking with him Kalb and eleven other officers. While Marie Antoinette applauded his generous self-devotion, the king forbade him to go, but he disregarded the order. His young wife, whom he deemed it prudent to leave behind, he consoled with the thought that the future welfare of all mankind was at stake in the struggle for constitutional liberty which was going on in America, and that where he saw a chance to be useful it was his duty to go. The able Polish officers, Pulaski and Kosciuszko, had come some time before.

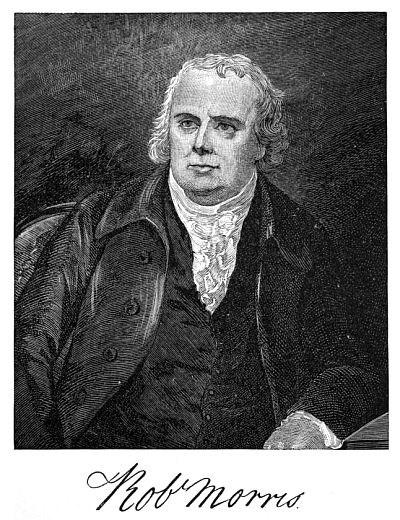

During the winter season at Morristown, Washington was busy in endeavouring to recruit and reorganize the army. Up to this time the military preparations of Congress had been made upon a ludicrously inadequate scale. There had been no serious attempt to create a regular army, but squads of militia had been enlisted for terms of three or six months, as if there were any likelihood of the war being ended within such a period. The rumour of Lord Howe’s olive-branch policy may at first have had something to do with this, and even after the Declaration of Independence had made further temporizing impossible, there were many who expected Washington to perform miracles and thought that by some crushing blow the invaders might soon be brought to terms. But the events of the autumn had shown that the struggle was likely to prove long and desperate, and there could be no doubt as to the imperative need of a regular army. To provide such an army was, however, no easy task. The Continental Congress was little more than an advisory body of delegates, and it was questionable how far it could exercise authority except as regarded the specific points which the constituents of these delegates had in view when they chose them. Congress could only recommend to the different states to raise their respective quotas of men, and each state gave heed to such a request according to its ability or its inclination. All over the country there was then, as always, a deep-rooted prejudice against standing armies. Even to-day, with our population of seventy millions, a proposal to increase our regular army to fifty thousand men, for the more efficient police of the Indian districts in Arizona and Montana, has been greeted by the press with tirades about military despotism. A century ago this feeling was naturally much stronger than it is to-day. The presence of standing armies in this country had done much toward bringing on the Revolution; and it was not until it had become evident that we must either endure the king’s regulars or have regulars of our own that the people could be made to adopt the latter alternative. Under the influence of these feelings, the state militias were enlisted for very short terms, each under its local officers, so that they resembled a group of little allied armies. Such methods were fatal to military discipline. Such soldiers as had remained in the army ever since it first gathered itself together on the day of Lexington had now begun to learn something of military discipline; but it was impossible to maintain it in the face of the much greater number who kept coming and going at intervals of three months. With such fluctuations in strength, moreover, it was difficult to carry out any series of military operations. The Christmas night when Washington crossed the Delaware was the most critical moment of his career; for the terms of service of the greater part of his little army expired on New Year’s Day, and but for the success at Trenton, they would almost certainly have disbanded. But in the exultant mood begotten of this victory, they were persuaded to remain for some weeks longer, thus enabling Washington to recover the state of New Jersey. So low had the public credit sunk, at this season of disaster, that Washington pledged his private fortune for the payment of these men, in case Congress should be found wanting; and his example was followed by the gallant John Stark and other officers. Except for the sums raised by Robert Morris of Philadelphia, even Washington could not have saved the country.

Another source of weakness was the intense dislike and jealousy with which the militia of the different states regarded each other. Their alliance against the common enemy had hitherto done little more toward awakening a cordial sympathy between the states than the alliance of Athenians with Lacedæmonians against the Great King accomplished toward ensuring peace and good-will throughout the Hellenic world. Politically the men of Virginia had thus far acted in remarkable harmony with the men of New England, but socially there was little fellowship between them. In those days of slow travel the plantations of Virginia were much more remote from Boston than they now are from London, and the generalizations which the one people used to make about the other were, if possible, even more crude than those which Englishmen and Americans are apt to make about each other at the present day. In the stately elegance of the Virginian country mansion it seemed right to sneer at New England merchants and farmers as “shopkeepers” and “peasants,” while many people in Boston regarded Virginian planters as mere Squire Westerns. Between the eastern and the middle states, too, there was much ill-will, because of theological differences and boundary disputes. The Puritan of New Hampshire had not yet made up his quarrel with the Churchman of New York concerning the ownership of the Green Mountains; and the wrath of the Pennsylvania Quaker waxed hot against the Puritan of Connecticut who dared claim jurisdiction over the valley of Wyoming. We shall find such animosities bearing bitter fruit in personal squabbles among soldiers and officers, as well as in removals and appointments of officers for reasons which had nothing to do with their military competence. Even in the highest ranks of the army and in Congress these local prejudices played their part and did no end of mischief.

From the outset Washington had laboured with Congress to take measures to obviate these alarming difficulties. In the midst of his retreat through the Jerseys he declared that “short enlistments and a mistaken dependence upon militia have been the origin of all our misfortunes,” and at the same time he recommended that a certain number of battalions should be raised directly by the United States, comprising volunteers drawn indiscriminately from the several states. These measures were adopted by Congress, and at the same time Washington was clothed with almost dictatorial powers. It was decided that the army of state troops should be increased to 66,000 men, divided into eighty-eight battalions, of which Massachusetts and Virginia were each to contribute fifteen, “Pennsylvania twelve, North Carolina nine, Connecticut eight, South Carolina six, New York and New Jersey four each, New Hampshire and Maryland three each, Rhode Island two, Delaware and Georgia each one.” The actual enlistments fell very far short of this number of men, and the proportions assigned by Congress, based upon the population of the several states, were never heeded. The men now enlisted were to serve during the war, and were to receive at the end a hundred acres of land each as bounty. Colonels were to have a bounty of five hundred acres, and inferior officers were to receive an intermediate quantity. Even with these offers it was found hard to persuade men to enlist for the war, so that it was judged best to allow the recruit his choice of serving for three years and going home empty-handed, or staying till the war should end in the hope of getting a new farm for one of his children. All this enlisting was to be done by the several states, which were also to clothe and arm their recruits, but the money for their equipments, as well as for the payment and support of the troops, was to be furnished by Congress. Officers were to be selected by the states, but formally commissioned by Congress. At the same time Washington was authorized to raise sixteen battalions of infantry, containing 12,000 men, three regiments of artillery, 3,000 light cavalry, and a corps of engineers. These forces were to be enlisted under Washington’s direction, in the name of the United States, and were to be taken indiscriminately from all parts of the country. Their officers were to be appointed by Washington, who was furthermore empowered to fill all vacancies and remove any officer below the rank of brigadier-general in any department of the army. Washington was also authorized to take whatever private property might anywhere be needed for the army, allowing a fair compensation to the owners; and he was instructed to arrest at his own discretion, and hold for trial by the civil courts, any person who should refuse to take the continental paper money, or otherwise manifest a want of sympathy with the American cause.

These extraordinary powers, which at the darkest moment of the war were conferred upon Washington for a period of six months, occasioned much grumbling, but it does not appear that any specific difficulty ever arose through the way in which they were exercised. It would be as hard, perhaps, to find any strictly legal justification for the creation of a Continental army as it would be to tell just where the central government of the United States was to be found at that time. Strictly speaking, no central government had as yet been formed. No articles of confederation had yet been adopted by the states, and the authority of the Continental Congress had been in nowise defined. It was generally felt, however, that the Congress now sitting had been chosen for the purpose of representing the states in their relations to the British crown. This Congress had been expressly empowered to declare the states independent of Great Britain, and to wage war for the purpose of making good its declaration. And it was accordingly felt that Congress was tacitly authorized to take such measures as were absolutely needful for the maintenance of the struggle. The enlistment of a Continental force was therefore an act done under an implied “war power,” something like the power invoked at a later day to justify the edict by which President Lincoln emancipated the slaves. The thoroughly English political genius of the American people teaches them when and how to tolerate such anomalies, and has more than once enabled them safely to cut the Gordian knot which mere logic could not untie if it were to fumble till doomsday. In the second year after Lexington the American commonwealths had already entered upon the path of their “manifest destiny,” and were becoming united into one political body faster than the people could distinctly realize.