полная версия

полная версияHistory of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, Vol. 1

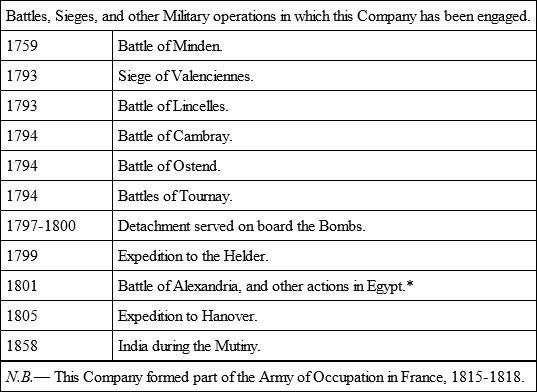

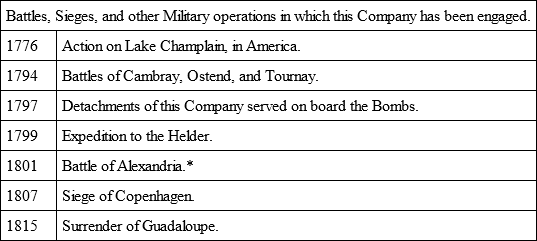

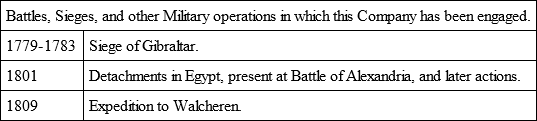

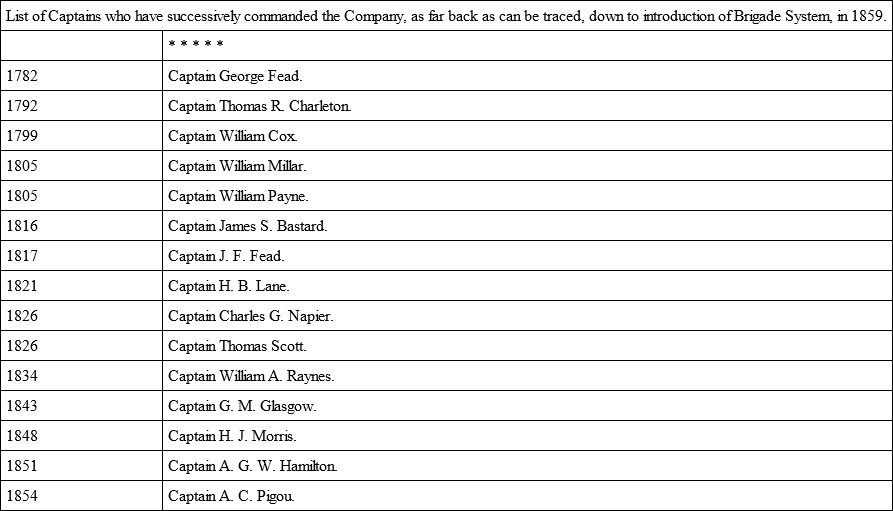

Now "7" BATTERY, 2nd BRIGADE.

No. 4

COMPANY, 1st BATTALION,

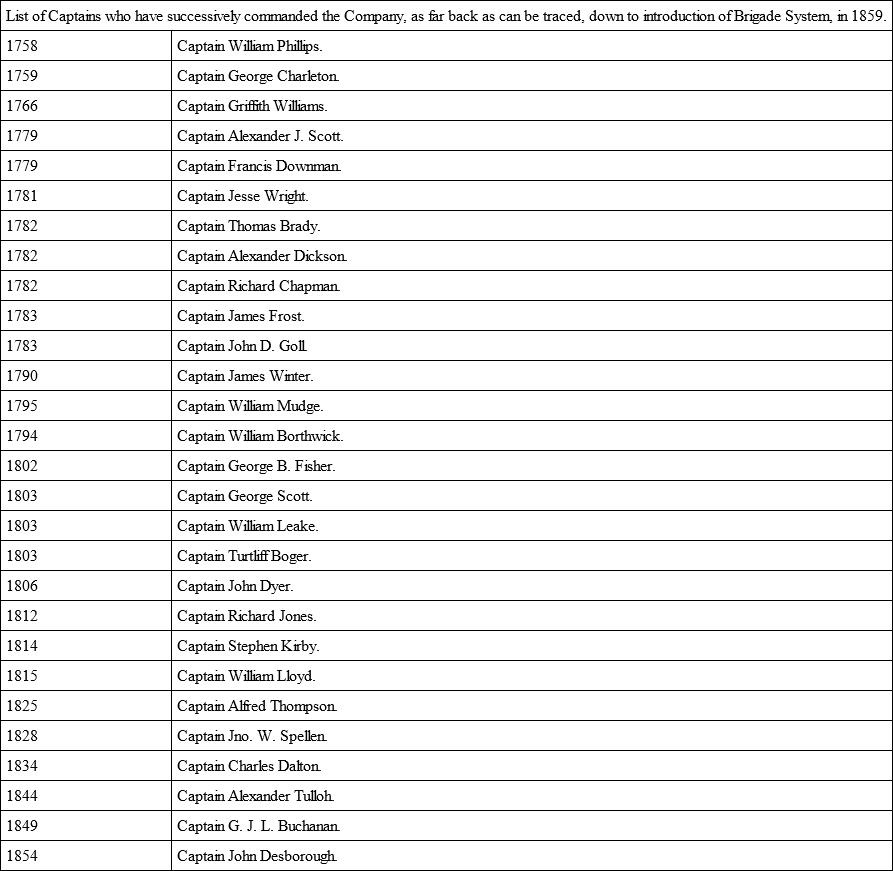

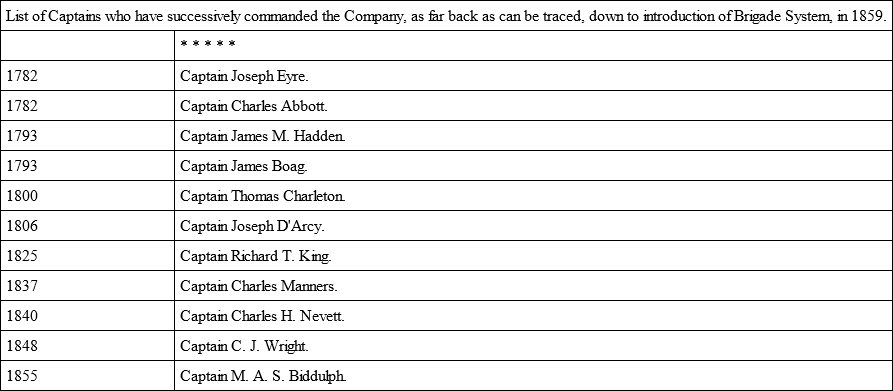

Now "3" BATTERY, 5th BRIGADE.

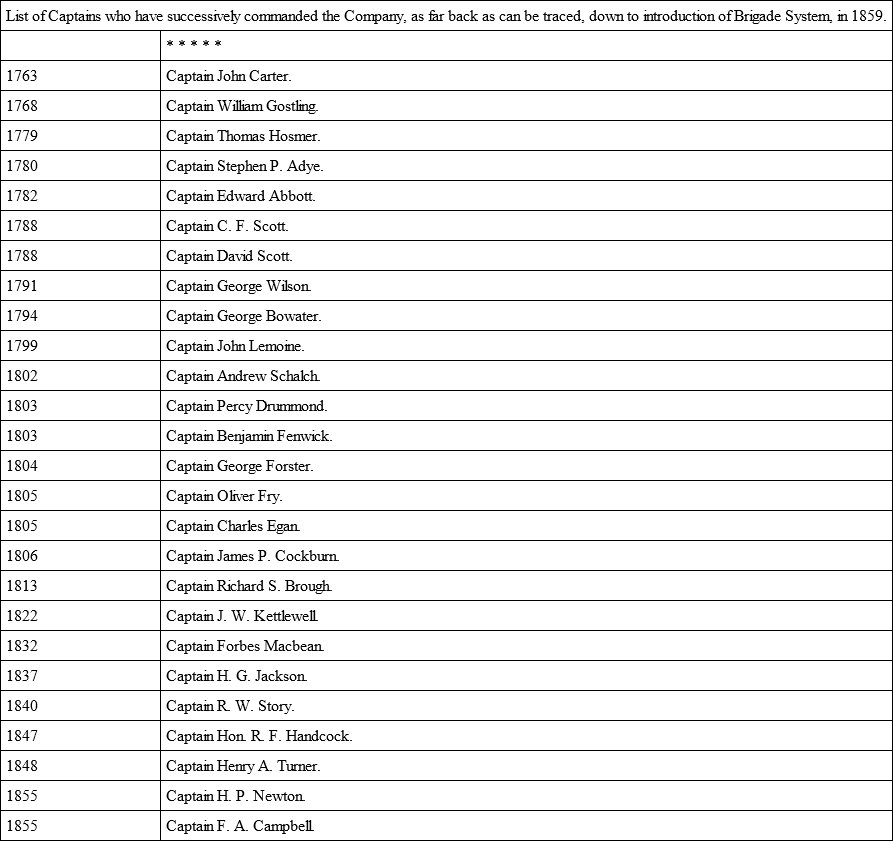

No. 5 COMPANY, 1st BATTALION,

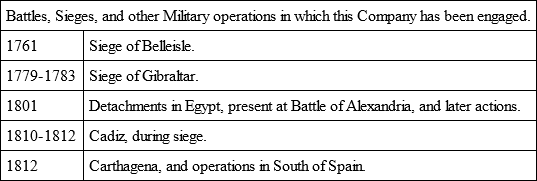

Now "4" BATTERY, 13th BRIGADE.

* By General Orders of 31st October and 1st November, 1803, the Officers, non-commissioned Officers, and Men of this Company were permitted to wear the "Sphynx" and "Egypt," on their Regimental Caps; but the distinction was a personal one, and not granted to the companies to be perpetuated.

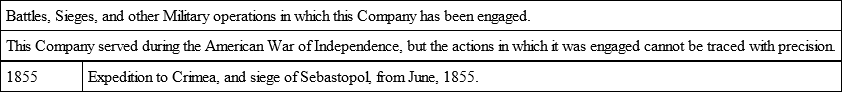

No. 6 COMPANY, 1st BATTALION,

Now "6" BATTERY, 2nd BRIGADE.

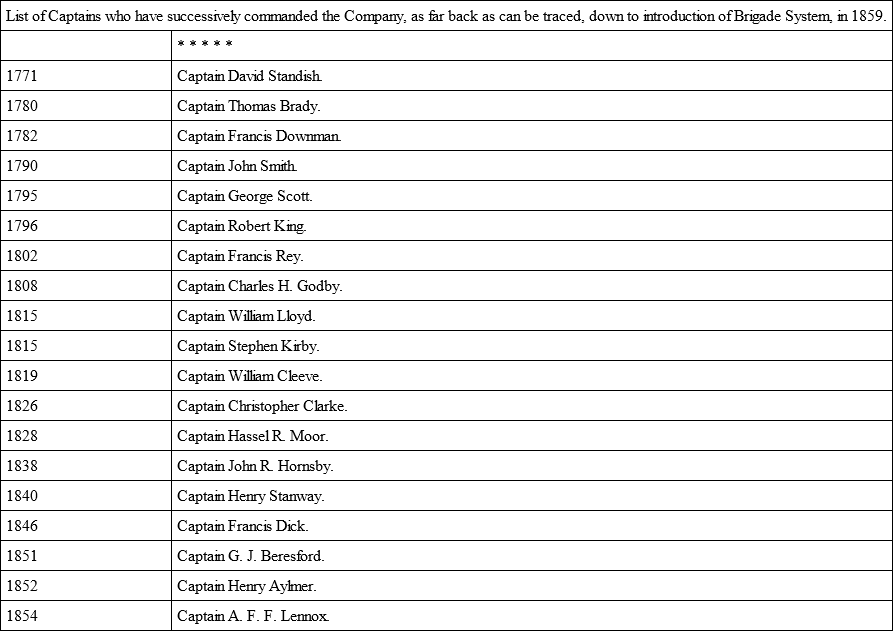

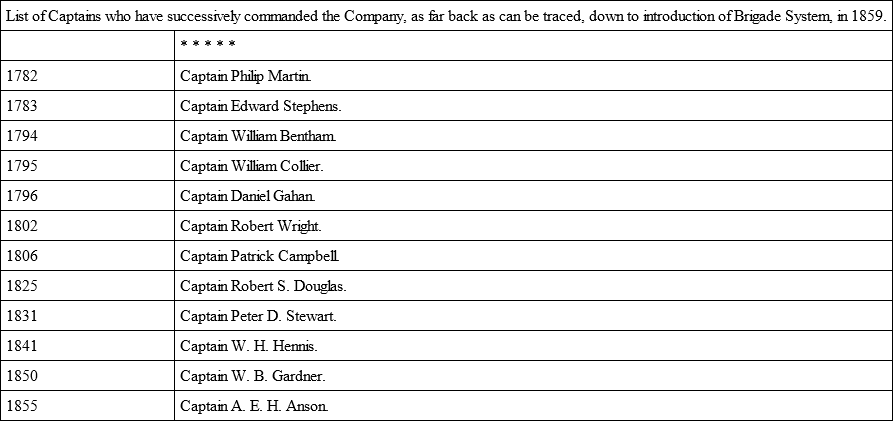

No. 7 COMPANY, 1st BATTALION,

Now "4" BATTERY, 5th BRIGADE.

* By General Orders of 31st October, and 1st November, 1803, the Officers, non-commissioned Officers, and Men of this Company were permitted to wear the "Sphynx," with "Egypt," on their Regimental Caps; but the distinction was a personal one, and not given to the companies to be perpetuated.

No. 8 COMPANY, 1ST BATTALION,

Now "A" BATTERY, 11th BRIGADE.

CHAPTER XVI.

The Second Battalion. – The History and PresentDesignation of the Companies

Formed in 1757, at the same time as the 1st Battalion, the 2nd Battalion at first included companies in all parts of the world – the East Indies, America, Gibraltar, and England. The Cadet Company belonged to it, and was one of the twelve which constituted the Battalion; but in 1758 another service company was added, making it, in respect of service companies, equal to the 1st Battalion.

Its strength in 1758 amounted to a total of 1385, divided into thirteen companies. This strength was reduced in the following year by the transfer of three companies to assist in the formation of the 3rd Battalion. One company was again added in 1761, and two taken away when the 4th Battalion was formed in 1771. During the American War two companies were again added, and the greatest strength of all ranks was 1145. In 1793 and 1794 it approached 1300; and during the Peninsular War its average strength was 1460. While the Crimean War lasted the Battalion consisted of eight companies, and its strength was as follows: – In 1854, 1216; in 1855, 1344; and in 1856, 1480.

The distinctive mark of this Battalion was the fact, that the only Artillery present during the memorable siege of Gibraltar belonged to it.

The early services of the companies are difficult to trace. One company, under Captain Hislop, was present at the defence of Fort St. George, Madras, when besieged by the French, in October, 1758. In November of the same year a company of the Battalion, under Captain P. Innes, embarked with General Barrington's expedition, for the attack of the Island of Martinique. This expedition was unsuccessful, but the troops were then ordered against Guadaloupe, which was taken on 1st May, 1759. In February, 1759, the siege of Fort St. George was raised by the French, Captain Hislop's Company receiving great praise for its conduct during the defence.

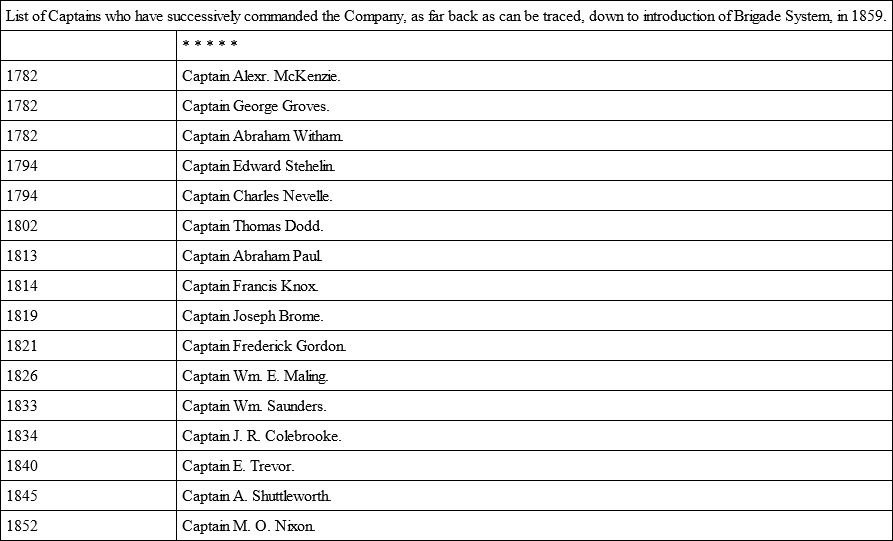

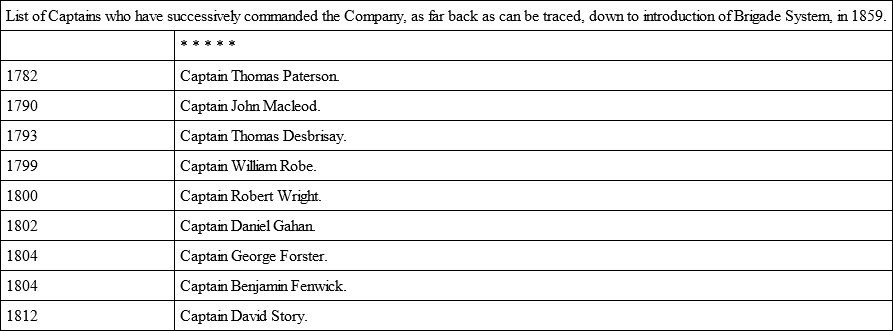

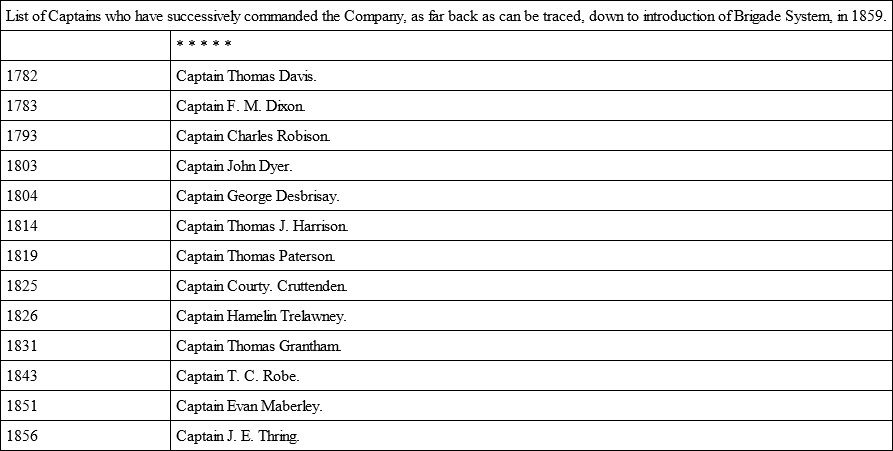

No. 1 COMPANY, 2nd BATTALION,

Now "7" BATTERY, 21st BRIGADE.

No. 2 COMPANY, 2nd BATTALION,

Now "2" BATTERY, 12th BRIGADE.

No. 3 COMPANY, 2nd BATTALION,

Now "7" BATTERY, 10th BRIGADE.

No. 4 COMPANY, 2nd BATTALION,

Now "D" BATTERY, 1st BRIGADE.

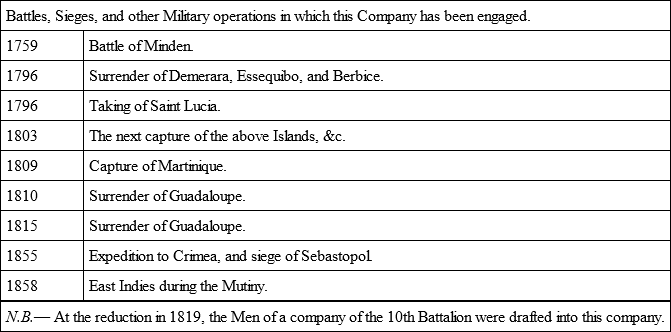

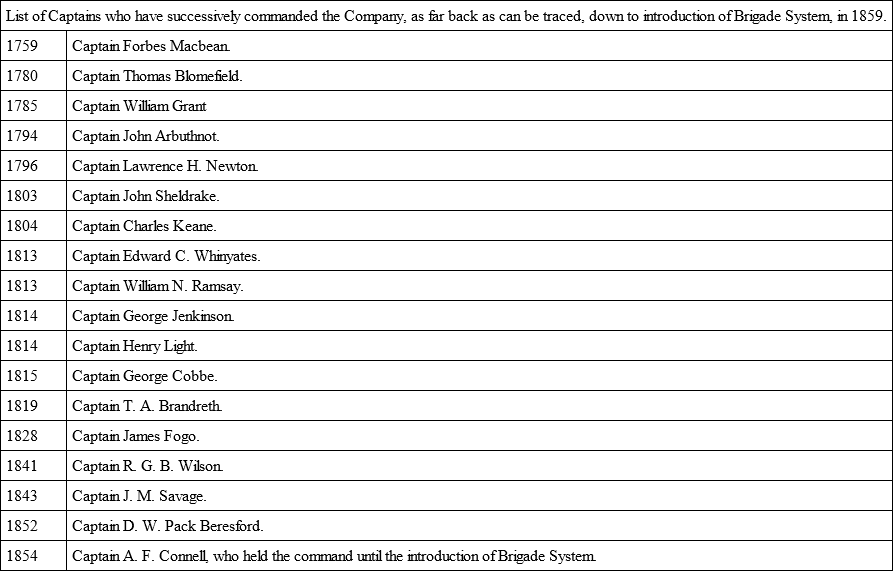

No. 5 COMPANY, 2nd BATTALION,

Now "8" BATTERY, 3rd BRIGADE.

No. 6 COMPANY, 2nd BATTALION,

Reduced on 1st March, 1819.

No. 7 COMPANY (afterwards No. 6), 2nd BATTALION,

Now "G" BATTERY, 8th BRIGADE.

No. 8 COMPANY (afterwards No. 7), 2nd BATTALION,

Now "5" BATTERY, 2nd BRIGADE.

No. 9 COMPANY, 2nd BATTALION,

Reduced 1st February, 1819.

No. 1 °COMPANY (afterwards No. 8), 2nd BATTALION,

Now "A" BATTERY, 14th BRIGADE.

CHAPTER XVII.

During the Seven Years' War

At this time the Regiment well deserved the motto it now bears, "Ubique." The feeling uppermost in the mind of one who has been studying its records between 1756 and 1763 is one of astonishment and admiration. Only forty years before, the Royal Artillery was represented by two companies at Woolwich; now we find it serving in the East and West Indies, in North America, in the Mediterranean, in Germany, in Belleisle, and in Britain, and yet it was by no means a large Regiment. In 1756 it contained eighteen companies, and by the end of the war it had increased to thirty, exclusive of the cadets; but when we reflect on the detached nature of their service, we cannot but marvel at the work they did. If England must always look back with pride to the annals of this war, so also must the Royal Artilleryman look back to this period of his Regimental History with amazement and satisfaction. It was a wonderful time, – a time bristling with ubiquitous victories, – a time teeming with chivalrous memories – Clive in the East, and Wolfe in the West – British soldiers conquering under Prince Ferdinand at Minden, under Lord Albemarle at the Havannah, under Amherst at Louisbourg, and under Hodgson at Belleisle, – English Artillerymen winning honours and promotion from a foreign prince in Portugal; and at the end, when the Peace of Paris allowed the nations to cast up the columns in their balance-sheet, England, finding Canada all her own, Minorca restored to her, and nineteen-twentieths of India acknowledging her sovereignty. It was a golden time: who can paint it? Who can select enough of its episodes to satisfy the reader, and yet not weary him with glut of triumph? And shall it be by continents that the deeds of our soldiers shall be watched? or on account of popular leaders? or by value of results?

With much thought and hesitation it has been resolved in this work to choose subjects for complex reasons. Who can think of England's Field Artillery without thinking, at such a time as this was, of Minden? – of her siege Artillery, without remembering Belleisle? And yet what would the History of the Regiment at such a period in England's annals be, if the names of Phillips, Macbean, and Desaguliers were unspoken?

Happy coincidence that enables the historian to combine both, – that bids him, as he writes of Minden, write also of Phillips, who was the head, and Macbean, who was the hand, of the corps on that proud day; and as he tells of the wet and miserable trenches at Belleisle, with the boom of its incessant bombardment, tell also of him, the brave, the learned Desaguliers, wounded, yet ever at his post! But is this all? The Seven Years' War, without America having a chapter given – America, which was the cradle of the war, as it was the scene of its greatest triumphs! Where shall we turn to choose on that continent some scene which shall be noble and pleasant to tell, and shall not wander from the purpose of this work? The mind clings instinctively to Wolfe, eager to narrate something of the Regiment's story over which his presence shall shed a lustre, in memory as in life. Quebec is eagerly studied, reluctantly laid aside, for on that sad and glorious day only a handful of Artillerymen mustered on the Plains of Abraham. So the student wanders backward from that closing scene, and on the shores of that bay in Cape Breton where Louisbourg once stood in arms, he finds a theme in which Wolfe and this Regiment, whose history he fain would write, were joint and worthy actors. And what prouder comrade could one have than he who was the Washington of England in bravery, in gentleness, in the adoration of his men?

These three episodes of the war, therefore, have been selected for separate mention. In the present chapter the general outline of the war will be glanced at, and domestic occurrences in the Regiment described.

The Seven Years' War owed its immediate origin to the quarrels in America between England and France. Under the impression that the time was favourable for recovering Silesia, which had been awarded to Prussia at the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, Austria secured Russia, Saxony, and Sweden as allies, and ultimately France; while Prussia obtained the alliance of England. The commencement of the war was unfavourable to England. Minorca and Hanover fell into the hands of the French, and remained so until the end of the war. But they were avenged by the victories of the British troops under Prince Ferdinand at Crevelt and Minden; and by the victories of the King of Prussia over the Austrians at Prague and Rosbach. The capture of Belleisle by the English compensated, to a certain extent, for the loss of Minorca. The capture of Louisbourg, Quebec, Montreal, and ultimately the whole of Canada, added lustre to the English arms in the West, as that of Pondicherry did in the East; while even Africa contributed its share to English triumph, in the capture of Senegal from the French.

It was not until 1758 that the first Artillery was sent to Germany. It was increased in the following year, and a further reinforcement was sent in 1760, increasing the whole to five companies. Two companies were sent to America in 1757, to swell the Artillery force already there, with a view to the reduction of Louisbourg and the subjugation of Canada. Two, besides a number of detachments, were at Belleisle in 1761; the company at Gibraltar was increased by another; two companies were sent to Portugal after France had formed the Treaty known as the Family Compact; four were in the East Indies; two companies, besides a number of detachments, accompanied Lord Albemarle to the Havannah; and a detachment went to Senegal. This summary – not including the numerous detachments on board the bomb-vessels – is sufficient to give some idea of the ubiquitous duties performed by the Regiment during this time.

The increase in the number of companies which took place during the Seven Years' War was accompanied by the formation of another Battalion (the Third), whose history will therefore, be given in proper chronological place.

Although three episodes have been selected for more detailed mention than the others, it would not be just to omit all notice of the other events which occurred in the Regiment's history at this time. Turning to the East, there are many pages in the old records which speak eloquently, though quaintly, of service done at this time by the corps in India. A mixed force, under the command of Captain Richard Maitland, R.A., was ordered by the Governor of Bombay to proceed, in February, 1759, against the City and Castle of Surat. Captain Maitland's and Captain Northall's companies were present with the force, but the last-named officer died of sunstroke on the march. "The first attack," writes Captain Maitland, "that we made was against the French garden, where the enemy (Seydees) had lodged a number of men. Them we drove out, after a very smart firing on both sides for about four hours, our number lost consisting of about twenty men killed and as many wounded. After we had got possession of the French garden, I thought it necessary to order the Engineer to pitch upon a proper place to erect a battery, which he did, and completed it in two days. On the battery were mounted two 24-pounders and a 13-inch mortar, which I ordered to fire against the wall, &c., as brisk as possible. After three days' bombarding from the batteries and the armed vessels, I formed a general attack, driving the enemy from their batteries, and carrying the outer town, with its fortifications. The same evening I commenced firing from the 13 and 10-inch mortars on the inner town and castle, distant 500 and 700 yards. The continual firing of our batteries caused such consternation, and the impossibility of supporting themselves caused the Governor to open the gates of the town, and offering to give up the castle if I would allow him and his people to march out with their effects. We got possession without further molestation." Captain Maitland, who seems to have been more proficient with his sword than his pen, died in India in 1763.

The scene changes to Manilla; and on a faded page the student reads how a company of Artillery arrived off that island on the 23rd September, 1762, with General Draper's force, and made good their landing next morning with three field-guns and one howitzer. By the 26th the batteries were ready for heavier ordnance; and eight 24-pounders were placed in one, and 10 and 13-inch mortars in another. And here the dim page is illumined by a sentence dear to the student's heart: – "The officers of Artillery and Engineers exercising themselves in a manner that nothing but their zeal for the public service could have inspired." On the 5th October, so violent had been the fire of the Artillery, that the breach appeared practicable; and at daylight on the morning of the 6th, after a general discharge from all the batteries, the troops rushed to the assault. The Governor and principal officers retired to the citadel, and surrendered themselves prisoners at discretion.

Again the scene changes. On the 5th March, 1762, Lord Albemarle's expedition left Portsmouth for the Havannah. The Royal Artillery consisted of Captain Buchanan's and Captain Anderson's companies, with Brevet-Lieutenant-Colonels Leith18 and Cleveland, Captain-Lieutenant Williamson as a Volunteer, and Lieutenants Lee, Lemoine, and Blomefield for duty on board the bomb-vessels. On reaching Barbadoes news is received of the capitulation of Martinique to General Monckton's force, and the fleet steers for that island. Here large reinforcements from America meet them, including Captain Strachey's company, which brings the strength of the Artillery up to 377 of all ranks. On the 6th June the expedition reaches Havannah, and a landing is effected six miles to the eastward of the Moro, which it is resolved to besiege first. And here the story becomes a purely Artillery matter. Two batteries were opened – one against the Moro, at 192 yards distance, called the grand battery, and one for howitzers, to annoy the shipping. Repeated and unsuccessful sallies were made by the enemy; and still battery after battery was made and opened by the English. On the 1st July four batteries opened fire – from twelve 24-pounders, six 13-inch, three 10-inch, and 26 Royal mortars. On the 3rd July another was completed; and on the 16th sixteen additional guns were brought into play and so well served that the besieged were reduced to six guns. But there were other enemies than man to contend with. Twice the Grand Battery took fire, and the second time it was entirely consumed. Fresh provisions became scarce, and water equally so. No words can paint what followed better than the short sentence which meets the student's eye: – "The scanty supply of water exhausted their strength, and, joined to the anguish of dreadful thirst, put an end to the existence of many. Five thousand soldiers and three thousand sailors were laid up with various distempers."19 On the 22nd, – a lodgment having been effected on the glacis, – it was found necessary to have recourse to mining; and on the 30th the mines were sprung and the place carried by storm. Fresh batteries were now formed, and the guns of the Moro turned against the town. On the 11th August forty-five guns and eight mortars opened on the town with such fury, that flags of truce were soon hung up all round the town, and on the following day the articles of capitulation were signed; the principal gates of the town were taken possession of; the English colours were hoisted; and Captain Duncan took possession of the men-of-war in the harbour.20

The death vacancies in the Artillery, which were very numerous, had been filled up on the spot by Lord Albemarle, who not merely gave the promotions, but also made first appointments as Lieutenant-Fireworkers from among the cadets and non-commissioned officers present with the companies. The whole of these promotions were ratified by the Board in the following year; but an opportunity was taken at the same time of informing the Regiment that "Lieutenant-Colonel Cleveland's brevet is not to allow of his ranking otherwise than as Major in the Regiment," although his pay would be that of the higher rank.

Yet again and again, from east to west and west to east, do the scenes in the Regimental drama at this time change. From Newfoundland we hear of a gallant band of fifty-eight Artillerymen under Captain Ferguson, with a train of no less than twenty-nine pieces, being present with Colonel Amherst at the recapture of that island, after its brief occupation by the French. And from Portugal comes a letter from Lord London in October, 1762: "In the action of Villa Vella, Major Macbean, with four field-pieces, joined, having used the greatest diligence in his march. The force retiring, Major Macbean's guns formed part of the rear-guard, which he conducted so effectually, that hardly any shot was fired that did not take place among the enemy… Major Macbean of the Artillery is an officer whose zeal and ability, upon this and every other occasion, justly entitle him to the warmest recommendations I can possibly give him."

In the mean time, what was going on in England?

An unsuccessful expedition was ordered in July, 1757, to Rochfort, in which Captain James's company was engaged. On its return in October the Company was sent to Scarborough.

On the 5th June, 1758, we find 400 Artillerymen with sixty guns forming part of an expedition against St. Malo under Charles, Duke of Marlborough; but little was done except destroying a large number of French vessels. The subsequent attack and capture of Cherbourg was more successful, and the number of guns taken from the enemy enabled the Government to get up a display in London – utterly out of proportion to the actual danger and loss incurred by the troops, but intended to gratify the populace – which may be described in a few words. "The cannon and mortars taken at Cherbourg passed by His Majesty, set out from Hyde Park and came through the City in grand procession, guarded by a company of matrosses, with drums beating and fifes playing all the way to the Tower, where they arrived at four o'clock in the afternoon. There were twenty-three carriages drawn by 229 horses, with a postilion and driver to each carriage in the following manner: – The first, drawn by fifteen grey horses, with the English colours and the French underneath; seven ditto, drawn by thirteen horses each; nine ditto by nine horses each; three ditto by seven horses each; one ditto by five horses; then the two mortars, by nine horses each."

And at Woolwich, what was going on? Promotion was brisk, with death so busy all over the world; officers got their commissions when very young; and the age of the cadets fell in proportion. Hence we feel no surprise that the legislation for these young gentlemen occupies a considerable part of the order-books of the period. But the remaining orders are not destitute of interest. One, dated 1st October, 1758, introduces a name which has been familiar to the Regiment ever since in the same capacity: "R. Cox, Esq., is appointed Paymaster to the Royal Regiment of Artillery." The division of the Regiment into Battalions rendered many orders necessary. It was now for the first time laid down that the quartermasters were responsible for the clothing and equipment until handed over to the captains. A separate roster was kept for detachments, which, however, was not to interfere with officers accompanying their own men, when the whole company moved. Promotion from matross to gunner was ordered never to be made without submitting the case to the Lieutenant-General of the Ordnance, in the same manner as the promotion of non-commissioned officers. No non-commissioned officer was to be recommended for promotion who had not written in full for the examination of his Captain the names and different parts of guns and mortars, their carriages and beds, and also a full description of a gyn. And at every parade the Captain of the week was to take care that the men were made acquainted with the names of all the different parts of a gun and carriage, and of a gyn, and once a day to mount and dismount a gun. Every man was supplied with three rounds of ball-cartridge, without which he was never to go on duty; when discharged, an English gunner received a fortnight's pay; a Scotchman received a month's, provided he had been enlisted in Scotland; no Irishman was on any account allowed at this time to be enlisted for the Royal Artillery; no recruit was permitted leave of absence until he had been dismissed drill; no man on guard was to "extort money from any prisoner on any pretence whatsoever;" no man was to pull off his clothes or accoutrements during the hours of exercise; no pay-sergeant was allowed to pay the men in a public-house; the drummers and fifers were, when on duty, always to wear their swords; any pay-sergeant lending money at a premium to any of the men was to be tried and reduced to the rank of matross, and any man consenting to be imposed upon in this respect would receive no further advancement in the Regiment. No men were allowed to enter the Laboratory in their new clothing. Every recruit for the Regiment at this time received a guinea and a crown as bounty, provided he were medically fit, 5 feet 9 inches in height, and not over 25 years of age.