полная версия

полная версияHistory of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, Vol. 1

Many of the orders would lose their quaintness, if curtailed.

November 19, 1758. "Complaint having been made of the Greenwich guard for milking the cows belonging to Combe Farm, the Sergeant of that guard to be answerable for such theft, who will be broke and punished if he suffer it for the future, and does not take care to prevent it."

Jan. 6, 1759. "The Paymasters of each company are to clear with the nurse of the hospital once a week. No man is to be allowed within the nurse's apartment."

March 19, 1759. "The sentries to load with a running ball, and when the Officer of the Guard goes his rounds, they are to drop the muzzles of their pieces to show him that they are properly loaded."

June 14, 1758. "In drilling with the Battalion guns the man who loads the gun is to give the word 'Fire,' as it is natural to believe he will not do it till he believes himself safe; and he who gives the word 'Fire' is not to attempt to sponge until he hears the report of the gun."

With regard to officers, the order-books at this time divided their attention pretty equally between the Surgeon and his mate, who had a playful habit of being out of the way when wanted, and that favourite theme, the young officers. Much fatherly advice, which in more modern times would be given verbally, was given then through the channel of the Regimental order-book. Nor was the system more successful, if one may judge from the frequent repetitions of neglected orders. Various orders as to dress were given, from which we learn that boots for the officers and black spatterdashes for the men were the ordinary covering for their extremities on parade – white spatterdashes with their six-and-thirty buttons being reserved for grand occasions. It was a very serious crime to wear a black stock, – white being the orthodox colour – and the lace from the officers' scarlet waistcoats was removed at this period. Very great attention was paid at this time to perfecting the officers, old and young, in the knowledge of laboratory duties, nor was any exemption allowed. From the order-books of this date, also, we learn that officers' servants were chosen from among the matrosses; and that, on a man becoming a gunner, he ceased to be a servant. Nor was a matross allowed to be made gunner until a recruit was found to fill his vacancy in the lower grade. As now, the practice prevailed then, whenever a man in debt was transferred from one company to another, of making the Captain who received the man reimburse the Captain who handed him over, repaying himself by stoppages from the man's pay.

With this general glance at the Regiment during the Seven Years' War, the History will now proceed to a somewhat fuller examination of the three important episodes in that War, which have been selected.

N.B.– Good service was rendered at Guadaloupe in 1759 by a Company under Major S. Cleaveland, and at Martinique in 1762 by two Companies under Lieutenant-Colonel Ord.

CHAPTER XVIII.

The Siege of Louisbourg

The year in which the Regiment was divided into two Battalions witnessed the commencement in America of military operations which were to result in the complete removal of French authority from Canada.

Captain Ord's company, which had suffered so grievously at Fort du Quesne in 1755, having been reinforced from England, was joined in 1757 by two companies under Colonel George Williamson, and a large staff of artificers, the whole being intended to form part of an expedition against the French town of Louisbourg in Cape Breton, now part of the province of Nova Scotia. It was to be Colonel Williamson's good fortune to command the Royal Artillery in America until, in 1760, the English power was fully established on the Continent.

When the English captured Annapolis and Placentia in the beginning of the 18th century, the French garrisons were allowed to settle in Louisbourg, which place they very strongly fortified. Its military advantages were not very great, had an attack from the land side been undertaken, for it was surrounded by high ground; but it had an admirable harbour, and it was very difficult to land troops against the place from the sea side of the town. The harbour lies open to the south-east, and is nearly six miles long, with an average depth of seven fathoms, and an excellent anchorage. There was abundance of fuel in the neighbourhood, both wood and coal; in fact, the whole island was full of both; and there were casemates in the town which could greatly shelter the women and children during a bombardment. Generally some French men-of-war were in the harbour; and in 1757, when the siege was first proposed to be undertaken, so strong was the French fleet at Louisbourg, that the English commanders postponed their operations until the following year. Had our statesmen been better acquainted with geography, it is probable that at the Peace of Utrecht, when Nova Scotia and Newfoundland were authoritatively pronounced to be English territory, Cape Breton would have also been included; but being an island, and separate from Nova Scotia although immediately adjoining it, the French did not consider that it fell within the treaty, and clung to it, as they always had to the maritime provinces of Canada.

The siege of 1758 was not the first to which Louisbourg had been subjected. In 1745 an expedition had been fitted out from Massachusetts – the land forces being American Militia under Colonel Pepperell, and the naval contingent being composed of English men-of-war under Commodore Warren. The amicable relations between the naval and military commanders tended greatly to bring about the ultimate success.

The American Militia were badly trained, and far from well disciplined, but they were brave, headstrong, and animated by strong hatred of their old enemies the French. Powerful as Louisbourg was (it was called the Dunkirk of America) the Americans did not hesitate to attack it, and they were justified by the result. On the 30th April, 1745, the siege commenced; on the 15th June, M. Du Chambon, the Governor of Louisbourg, signed the capitulation.

For a year after this, the town was occupied by the American Militia; but a garrison which included a company of the Royal Artillery was then sent from England, and remained until 1748, when by the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle Louisbourg was restored to the French. The sum of 235,749l. was paid by England to her American colonies, to meet the expenses of the expedition whose success had now been cancelled by diplomacy, and if to this sum be added the expenses of the Navy, and the cost of garrisoning the place for three years, we shall find that at least 600,000l. must have been expended to no purpose.

Time went on; treaties were torn up; and Louisbourg was again the object of English attack. It is this second siege which is the one considered in this chapter; for none of the Royal Artillery were present at the first; the Artillery which fought on that occasion being militia, commanded by an officer who fought against England during the subsequent War of Independence. An indirect interest certainly is attached to that siege in the mind of one studying the annals of the Royal Artillery; for had it been unsuccessful, Annapolis with its little garrison would have been exposed to another assault. From private letters in possession of the descendants of a distinguished Artillery officer – Major-General Phillips – the perilous condition of that town during 1745 can be easily realized. Large bodies of French, and of hostile Indians, were in the immediate neighbourhood, making no secret of their intention to attack Annapolis in force, should the English siege of Louisbourg be unsuccessful. With the news of its capture, the danger to Annapolis disappeared. These local wars between the French and English settlers proved an admirable school for instructing the New Englanders in military operations; nor was it foreseen that the experience thus acquired would be turned against the parent country. Distraction in America helped England in her wars with France in Europe; and such distractions were easy to raise among colonists whose mutual hatred was so great. It was never imagined that the tools which England thus used against France were being sharpened in the process for use against herself in the stern days which were coming on. Colonial rebellion seemed impossible; colonial endurance was believed to be eternal; it was hoped that patriotism and sentiment would be stronger than any hardship, and would condone any injustice. But when the day came when colonists asked the question "Why?" for the Imperial actions towards them, the parental tie was cut, and the lesson taught in the school of local warfare – the lesson of their own strength – became apparent to the children.

The siege of Louisbourg, in 1758, has a threefold interest to the military reader; in connection with the conspicuous services of the Royal Artillery on the occasion; in relation to the story of the gallant Wolfe, who acted as one of the Brigadiers; and in the fact that this was the last place held by the French against England, on the east coast of America. Ghastly for France as the results of the Seven Years' War were, perhaps none were felt more acutely than this loss of Canada, with its episodes of Louisbourg and Quebec. Louis the Well-beloved was sinking into a decrepit debauchee; and in the East and in the West his kingdom was crumbling away. The distinctive characteristics, even at this day, of the French population of Canada, which have survived more than a century of English rule, give an idea of the firm hold France had obtained on the country; and the strength of that hold must have made the pang of defeat proportionately bitter.

Lord Loudon was to have commanded the expedition; and in 1757 the necessary troops and ships were concentrated at Halifax, now the capital of Nova Scotia. But on learning that there were 10,300 of a garrison in Louisbourg, besides fifteen men-of-war and three frigates, he abandoned the idea of an attack, and sailed for New York, leaving garrisons in Halifax and Annapolis.

In the following year, the idea was revived; and General Amherst left Halifax for Louisbourg with a force of 12,260 men, of whom 324 belonged to the Royal Artillery. The naval force consisted of 23 ships of the line and 18 frigates; and the number of vessels employed as transports was 144.

The Artillery train included 2 Captain-Lieutenants, 6 First Lieutenants, 5 Second Lieutenants, and 4 Lieutenant-Fireworkers; besides a staff consisting of a Colonel, an Adjutant, a Quartermaster, and two medical officers. There were no less than 53 non-commissioned officers, to a total rank and file of 63 gunners and 163 matrosses.

The Regiments engaged were as follows: – the 1st Royals, 15th, 17th, 22nd, 28th, 35th, 40th, 45th, 47th, 48th, 58th, two battalions of the 60th Royal Americans, and Frazer's Highlanders. There were eleven officers of miners and engineers, and they were assisted during the siege, and at the demolition of the fortifications, by selected officers from the Infantry Regiments. General Amherst was assisted by the following Brigadiers: – Whitmore, Lawrance, and James Wolfe.

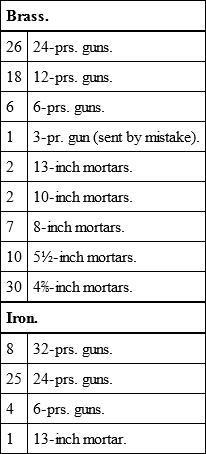

The following guns were taken with the Artillery: —

There were also two 8-inch and four 5½-inch howitzers. Over 43,000 round shot, 2380 case, 41,762 shell, besides a few grape and carcasses, and 4888 barrels of powder accompanied the train.

The fleet was commanded by Admiral Boscawen, assisted by Vice-Admiral Sir Charles Hardy, and Commodore Durell. It consisted, as has been said, of no less than 23 ships of the line, and 18 frigates. Even the harbour of Halifax, Nova Scotia, which has been the witness of so many historical scenes, never saw a finer sight than when on Sunday the 28th May, 1758, this fleet, accompanied by the transports, sailed for Louisbourg. All the arrangements for the embarkation and the siege had been made by Brigadier Lawrance, at Halifax, even down to such details as the prescription of ginger and sugar for the troops, for the purpose of neutralizing the evil effects of the American water – an evil which must certainly have existed in the Brigadier's imagination. But just as they left the harbour, and reached Sambro' Point, they met a vessel from England with General Amherst on board, commissioned to take command of the expedition, as far as the military forces were concerned. The cordial relations between him and Admiral Boscawen assisted, to a marked extent, in bringing about the success of the enterprise.

The orders issued to the troops were intended to excite them to anger against the enemy, at the same time that they should inculcate the strongest discipline. The quaintness of some of them renders them worthy of reproduction. "No care or attention will be wanting for the subsistence and preservation of the troops, such as our situation will admit of. There will be an Hospital, and in time it is hoped there will be fresh meat for the sick and wounded men… The least murmur or complaint against any part of duty will be checked with great severity, and any backwardness in sight of the enemy will be punished with immediate death. If any man is villain enough to desert his colours and go over to the enemy, he shall be excepted in the capitulation, and hanged with infamy as a traitor. When any of our troops are to attack the French regular forces, they are to march close up to them, discharge their pieces loaded with two bullets, and then rush upon them with their bayonets; and the commander of the Highlanders may, when he sees occasion, order his corps to run upon them with their drawn swords… A body of light troops are now training to oppose the Indians, Canadians, and other painted savages of the Island, who will entertain them in their own way, and preserve the women and children of the Army from their unnatural barbarity. Indians spurred on by our inveterate enemy, the French, are the only brutes and cowards in the creation who were ever known to exercise their cruelties upon the sex, and to scalp and mangle the poor sick soldiers and defenceless women. When the light troops have by practice and experience acquired as much caution and circumspection, as they have spirit and activity, these howling barbarians will fly before them… The tents will be slightly intrenched or palisaded, that the sentries may not be exposed to the shot of a miserable-looking Mic-Mac, whose trade is not war, but murder… As the air of Cape Breton is moist and foggy, there must be a particular attention to the fire-arms upon duty, that they may be kept dry, and always fit for use; and the Light Infantry should fall upon some method to secure their arms from the dews, and dropping of the trees when they are in search of the enemy."

After a favourable passage, the fleet anchored in Gabreuse Bay, on Friday the 2nd June. This bay is about three leagues by sea from Louisbourg harbour, and to the southwest of it. Here it was resolved to attempt a landing; but for days the elements fought for the French. Incessant fogs and a tremendous surf rendered the enterprise hopeless, until Thursday, the 8th June. The landing was ultimately effected under the fire of the ships; the leading boats containing the four senior companies of grenadiers, and all the light infantry of the force, under General Wolfe, whose courage and skill on this occasion were conspicuous. With a loss of 111 killed and wounded, they succeeded in driving the enemy back, and the other regiments were able to land. A change of weather prevented the landing of Artillery, baggage, and stores, so that the troops were exposed for the night to great discomfort. The spirit of the men under Wolfe on this occasion was remarkable. Boats were swamped, or dashed to pieces on the rocks; many men were drowned; and all had to leap into the water up to the waist; but nothing could restrain their ardour. Not merely did they drive the enemy back, but they captured 4 officers and 70 men, and 24 pieces of Ordnance.

From this day until the 19th, when the Royal Artillery opened upon the town from a line of batteries which had been thrown up along the shore, the operations of the army were weary and monotonous in the extreme. With the exception of Wolfe's party, which was detached to secure a battery called the Lighthouse Battery, – an undertaking in which he succeeded, the duties of the troops consisted in making roads, and transporting from the landing-place guns, ammunition, and stores. In all the arrangements for the investment and bombardment, Colonel Williamson was warmly supported by General Amherst; and the Admiral lent his assistance by landing his marines to work with the Artillery, and by sending four 32-pounders with part of his own ship's company, for a battery whose construction had been strongly recommended. It was nearly ten o'clock on the night of the 19th, when the English batteries opened on the shipping and on the Island Battery. This last was a powerful battery commanding the entrance to the harbour, and with a double ditch to the land side to strengthen it. It was the chief obstacle to the English movements, and smart as our fire was, it returned it with equal warmth. A battery of six 24-pounders was thrown up at the lighthouse for the sole purpose of attempting to silence this particular battery; and on the 25th it succeeded. The fire on the rest of the fortifications of Louisbourg was marvellously true, and incessant; and as of late years they had been somewhat neglected, and in many places sea-sand had been used with the mortar in their construction, the effect of the English fire was more rapidly apparent.

One precaution had been taken on this occasion by the French, which had been omitted by them in 1745, as they had too good reason to remember. When compelled to evacuate the Grand Battery, they set fire to it, and rendered it utterly useless; so that the course pursued by the English in the former siege, when they turned the guns of the battery against the town, could not be repeated. The effects of the English fire in the siege of 1758, when the Royal Artillery was represented, were thus described by a French officer who was in the town: – "Each cannon shot from the English batteries shook and brought down immense pieces of the ruinous walls, so that, in a short cannonade, the Bastion du Roi, the Bastion Dauphin, and the courtin of communication between them, were entirely demolished, all the defences ruined, all the cannon dismounted, all the parapets and banquettes razed, and became as one continued breach to make an assault everywhere."21

An attempt was made by the Governor of Louisbourg to procure a cessation of fire against a particular part of the works, behind which he said was the hospital for the sick and wounded. As however, there were shrewd reasons for believing that not the hospital, but the magazine, was the subject of his anxious thoughts, his request was refused, but he was informed that he might place his sick on board ship, where they would be unmolested, or on the island under our sentries. These offers, however, were not accepted.

The fire of the enemy's Artillery slackened perceptibly about the 13th July, and continued getting feebler, so that in a fortnight's time an occasional shot was all that was fired. At the commencement of the siege there were in Louisbourg 218 pieces of ordnance, exclusive of 11 mortars; but such was the effect of the English fire, not merely in dismounting and disabling the guns, but (as the deserters reported) in killing and wounding the gunners, that some days before the 27th July, when the capitulation was signed, the French reply to our Artillery fire was simply nil. The gallantry of the French commandant, the Chevalier de Drucour, was undoubted; but he was sorely tried by the fears and prayers of the unhappy civil population, to whom military glory was a myth, but a bombardment a very painful reality. Madame de Drucour did all in her power to inspire the troops with increased ardour; while there were any guns in position to fire, she daily fired three herself; and showed a courage which earned for her the respect both of friend and enemy. But misfortunes came fast upon one another. A shot from the English batteries striking an iron bolt in the powder magazine of the French ship 'Entreprenant,' an explosion followed, which set fire to her, and to two others alongside, the 'Capricieuse' and 'Superbe.' The confusion which ensued baffles description; and not the least startling occurrence was the self-discharge of the heated guns in the burning ships, whose shot went into the town, and occasionally into the other two men-of-war which had escaped a similar fate to that which befell the three which have been named. Four days later, on the 25th July, a party of 600 British sailors entered the harbour, boarded the only two ships which remained, the 'Prudent' and 'Bienfaisant,' set fire to the former, which had gone aground, and towed the latter out of the harbour to the English fleet.

Their batteries being destroyed, the fortifications one vast breach, their ships of war burnt or captured, and there being no prospect of relief, the French commander had no alternative but capitulation. He first proposed to treat, but was informed in reply, that unless he capitulated in an hour the English fleet would enter the harbour and bombard the town. So, after a little delay, he consented, on condition that the French troops should be sent as prisoners of war to France.

The articles of capitulation were signed on the 27th July, 1758, and immediately three companies of grenadiers took possession of the West Gate, while General Whitmore superintended the disarming of the garrison.

The expenditure of ammunition by the Royal Artillery during the siege was as follows: – 13,700 round shot, 3340 shell, 766 case shot, 156 round shot fixed, 50 carcasses, and 1493 barrels of powder. Eight brass, and five iron guns were disabled; and one mortar.

Of the English army, 524 were killed or wounded; and at the capture of the place, there were 10,813 left fit for duty. The total strength of the French garrison, including sailors and marines on shore, at the same date, was 5637 of all ranks, of whom 1790 were sick or wounded.

After the capitulation many of the English men-of-war moved into the harbour; and the demolition of the fortifications by the Engineers and working-parties was methodically commenced. The approach of the winter, and the heavy garrison duties, suspended the work for a time; and it was not until the 1st June, 1760, that the uninterrupted destruction of the works was commenced, under Captain Muckell of the Company of Miners, assisted by working parties from the infantry, of strength varying according to the work, from 160 to 220 daily. The miners and artificers numbered a little over 100. The whole work was completed on the 10th November, 1760, there having been only two days' intermission, besides Sundays, one being the King's birthday, and the other being Midsummer Day. The reason for keeping this latter day is thus mentioned in a MS. diary of the mining operations at Louisbourg, now in the Royal Artillery Record Office, which belonged to Sir John Ligonier: – "According to tradition among the miners, Midsummer was the first that found out the copper mines in Cornwall, for which occasion they esteem this a holy day, and all the miners come from below ground to carouse, and drink to the good old man's memory."

The fortifications of Louisbourg have never been rebuilt; and with the disappearance of its garrison its importance vanished. Cape Breton and the Island of St. John, now called Prince Edward's Island, fell into English hands almost immediately, and have never since been ruled by any other. The former is now part of Nova Scotia; its capital is no longer Louisbourg, but Sydney; and its French population has vanished – being replaced, to a great extent, by Highlanders from Scotland.

Although the purpose of this work has made the Artillery part of the army's duties the most prominent in the chapter, it cannot be denied that, to the ordinary reader, Wolfe is the centre of attraction. The time was drawing near when the brave spirit which animated him at Louisbourg was to fire his exhausted and weary frame, and raise him from his sickbed to that encounter on the Plains of Abraham, which his own death and that of his opponent were to render famous for all time. And the fire which then breathed life for the moment into his own frame inspired the men under his command at Louisbourg. The foremost duties, the posts of danger, were always his; and with such a guide his followers never failed. On one evening in June he was issuing orders to his division, which was to be employed during the night in bringing up guns to a new and exposed post. It was necessary to warn the men that the fire of the enemy would be probably warmer than usual, to check the working-parties: but with simple confidence, he said, "He does not doubt but that the officers and soldiers will co-operate with their usual spirit, that they may have at least their share in the "honours of this enterprise." Of a truth, he who asks his men to do nothing that he will not do himself, – who trusts them, instead of worrying and doubting them, – and who holds before his own eyes and theirs that ideal of duty which is of all virtues the most God-like, is the man to lead men; and such a man was Wolfe.