полная версия

полная версияHistory of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, Vol. 1

The melancholy fate of this expedition is well known. The detachment of Artillery was cut to pieces at Fort du Quesne, on that ghastly July day in 1755; the whole ten guns were taken; but Captain Ord himself survived to do good service years after, on the American continent. It will be remembered by the reader that George Washington fought on this occasion on the English side, and displayed the same marvellous coolness and courage, as he did on every subsequent occasion.

But events were ripening at Woolwich for great Regimental changes. A small subaltern's detachment left for Dublin, which was to be the parent of the Royal Irish Artillery, a corps which will form the subject of the next chapter. In 1756, a company of miners was formed for service in Minorca, which, on its return to Woolwich, was incorporated into the Regiment, and two other companies having been raised in the same year, and four additional in 1757, there was a total, including the companies of miners and cadets, of twenty-four companies. The largely increased number of company officers, in proportion to the limited number of those in the higher grades, made the prospects of promotion so dismal, that the Regiment was divided into two Battalions, each of which will receive notice in subsequent chapters.

CHAPTER XIV.

The Royal Irish Artillery

The Ordnance Department in Ireland was independent of that in England until the year 1674, when Charles II., availing himself of the vacancy created by the death of the then Irish Master-General – Sir Robert Byron – merged the appointment in that of the Master-General of England; and the combined duties were first performed by Sir Thomas Chicheley. This officer appointed, as his deputies in Ireland, Sir James Cuff and Francis Cuff, Esq. The Masters-General of the Irish Ordnance, whom we find mentioned after this date, were subordinate to the English Masters-General, in a way which had never previously been recognized.

Even after the amalgamation, however, the accounts of the Irish and British Departments of the Ordnance were kept perfectly distinct. When ships were fitted out for service in the Irish seas, their guns and stores were furnished from the Irish branch of the Ordnance. All gunpowder for use in Ireland was issued by the English officials to the Irish Board on payment; and the lack of funds, which was chronic at the Tower during the reigns of the Stuarts, was not unfrequently remedied by calling in the assistance of the Irish Board. Tenders for the manufacture of gunpowder having been received, and the orders then given having been complied with, it was no unusual thing to pay the merchants with Ordnance Debentures, and to ship the powder to Ireland in exchange for a money payment. The correspondence between the two Boards throws light upon the way in which money was found for the English fortifications, and also gives us the value of gunpowder at various times. For example, in August, 1684, one thousand barrels were shipped to Ireland; and the sum received in payment – 2500l.– was ordered to be spent on the fortifications at Portsmouth.

Some of the debentures issued to the creditors of the English Ordnance, in lieu of money, were on security of the grounds in the City of London, called the Artillery Grounds, and carried interest at the rate of two per cent.: others were merely promissory notes issued by the Board, which bore no very high reputation, nor were they easily convertible into money. From certain correspondence in the Tower Library, during the reigns of Charles II. and James II., it would appear that the Board could not be sued before the Law Courts for the amount of their debts; – the letter-books of that period teeming with piteous appeals from the defrauded creditors.

One unhappy man writes that in consequence of the inability of the Board to meet his claims, he "had undergone extreme hardships, even to imprisonment, loss of employment, and reputation." Another in the same year, 1682, writes, that "he is in a very necessitous and indigent condition, having not wherewithal to supply his want and necessity; and he doth in all humility tender his miserable condition to your Honours' consideration."

During periods of actual or expected disturbance in Ireland, stores for that country were often accumulated in Chester, and on the Welsh coast, ready for shipment; from which it may be inferred, that the arrangements in Ireland for their safe keeping were inadequate.

The formation of a battalion of Artillery on the Irish establishment was not contemplated until the year 1755, when, on the requisition of the Lord-Lieutenant, a party of twenty-four non-commissioned officers and men of the Royal Artillery, under the command of a First Lieutenant, left Woolwich for Dublin, for that purpose. This detachment, having received considerable augmentation and a special organization, was in the following year styled "The Artillery Company in Ireland," the commissions of the officers being dated the 1st of April, 1756. The company consisted of a Major, a Captain, one First and one Second Lieutenant, three Lieutenant-Fireworkers, five Sergeants, five Corporals, one hundred and six Bombardiers, thirty-four Gunners, one hundred and two Matrosses, and two Drummers. The large number of Bombardiers suggests a special service, probably in the bomb-vessels, for which this class was employed. Major Brownrigg, the commandant of the corps, was replaced in 1758, by Major D. Chevenix, from the 11th Dragoons. Two years later, the company was considerably increased, and was styled the "Regiment of Royal Irish Artillery." It had now a Colonel-in-Chief, and another en seconde, a Lieutenant-Colonel commandant, a Major, four Captains, four First and four Second Lieutenants, and four Lieutenant-Fireworkers. The Masters-General of the Irish Ordnance were ex officio Colonels-in-Chief of the Irish Artillery. The following is a list of those who held this appointment during the existence of the corps: James, Marquis of Kildare, Richard, Earl of Shannon, Charles, Marquis of Drogheda, Henry, Earl of Carhampton, and the Hon. Thomas Pakenham.

Reductions were made in the Regiment at the conclusion of peace in 1763, and again in 1766; but they were chiefly confined to weeding the Regiment of undersized men. In 1774, the rank of Lieutenant-Fireworker was abolished, three years later than the same change had been made in England. In 1778, the Regiment was augmented from four to six companies, the total of the establishment being raised from 228 to 534; and from that date the senior first lieutenant received the rank of Captain-Lieutenant. A further addition of seventy-eight gunners raised the total to 612, and caused an increase in the number of officers, four Second Lieutenants being added in 1782.

In August, 1783, an invalid company was added, consisting of a captain, first and second lieutenant, one sergeant, two corporals, one drummer, three bombardiers, four gunners, and thirty-nine matrosses, and with a few additions to the marching companies raised the establishment to 701. But in three months, a most serious reduction can be traced, not in the cadres, nor among the higher commissioned ranks, but among the subalterns, and the rank and file, and the total fell to 386.

By the monthly returns for October, 1783, we find that the title of matross, although retained in the invalid company, was otherwise abolished; the private soldiers being now all designated gunners. From 1783 to 1789, the establishment remained at 386; and in 1791, it was the same. The returns for the intermediate year have been lost.

In 1793, recruiting on a large scale can be traced, and we find, that in October, 1794, by successive augmentations, the establishment had reached a total of no less than 2069 of all ranks, organized into one invalid and twenty marching companies. By a King's letter, dated 20th May, 1795, these were constituted into two Battalions, the company of invalids remaining distinct. This gave an addition of thirteen Field and Staff Officers, and three Staff Sergeants, raising the total establishment from 2069 to 2085. Each company consisted of 100 of all ranks – except the invalid company, which remained at a total of fifty-three, until 1st October, 1800, when it was raised to 100 – and the strength of the Regiment reached its maximum, 2132.

This establishment continued, until the 1st of March, 1801, when, in anticipation of the amalgamation with the Royal Artillery, eight companies, with a proportion of Field Officers, were reduced, followed next month by a reduction of two more.

On the 1st April, 1801, the remaining ten marching companies, with Field and Staff Officers, were incorporated with the Royal Artillery, and numbered as the 7th Battalion of that corps. By General Order of 17th September, 1801, the invalid company was transferred to the battalion of invalids on the British establishment.

It was a singular coincidence that the officer of the Royal Artillery, who forty-six years before had left Woolwich to organize the first company of the Royal Irish Artillery, should, on the amalgamation, have been the Colonel commandant of the new Battalion. Lieutenant-General Straton had proceeded, in May, 1755, to Ireland, for the former purpose, and he rejoined the Royal Artillery on the 1st April, 1801, as Colonel commandant of the 7th Battalion. He died in Dublin on the 16th May, 1803, after a service of sixty-one years.

At the time of the amalgamation, six of the companies were stationed in Ireland, and four in the West Indies. The Irish Artillery was not exempt from foreign service, and the conduct of the men abroad was as excellent as it always was during the times of even the greatest civil commotion. When, however, they left Ireland on service, their pay became a charge on the English Office of Ordnance; and in the Returns from their own head-quarters we find that any men who might be in England, pending embarkation, were shown as "on foreign service."

The first employment of the Irish Artillery abroad was during the American war. In March, 1777, seventy men embarked, under the command of an officer of the Royal Artillery, and did duty with that corps in a manner which called forth the highest commendations from the officers under whom they served. The Master-General of the Ordnance, Lord Townsend, in a letter to the officer commanding the Irish Artillery, dated 23rd of December, 1777, alludes to these men in the following terms: "I am informed that none among the gallant troops behaved so nobly as the Irish Artillery, who are now exchanged, and are to return. I am sorry they have suffered so much, but it is the lot of brave men, who, so situated, prefer glorious discharge of their duty to an unavailing desertion of it."

The conduct of the Irish Artillery, both in America and in the darkest period of their service, in the West Indies, contrasts so strongly with that of the men enlisted in Ireland for the Royal Artillery at the same time, that evidently the recruiting for the latter corps must have been grossly mismanaged, or, what is more probable, the national corps obtained with ease the best men, while the refuse of the country was left to the recruiting sergeants of the Royal Artillery. In the correspondence of General Pattison, who at one period of the American war commanded the Royal Artillery on that continent, the language employed in describing the recruits enlisted in Ireland, and sent to join the 3rd and 4th Battalions in America, would be strong in any one, but is doubly so, coming from an officer always most courteous in his language, and by no means given to exaggeration.

Three companies of the Irish Artillery embarked for the Continent in 1794, and served in Flanders and the Netherlands, under the Duke of York. But, as has already been hinted, the most severe foreign service undergone by the corps was in the West Indies. In 1793, three companies embarked for these islands, and took honourable part during the following year, in the capture of Martinique, Guadaloupe, and St. Lucia, as well as in the more general operations.

Their strength, on embarkation, had been 15 Officers and 288 non-commissioned officers and men. In less than two years, only forty-three of the men were alive, and of the officers, only four returned to Europe. It accordingly became necessary to reinforce the companies by drafts from Ireland; and in addition to these, two other companies sailed in the winter of 1795; thus bringing the total strength serving in the West Indies to 500 of all ranks. In less than two years, a further reinforcement of 176 officers, non-commissioned officers, and men, was found necessary to repair the ravages of the climate upon the troops; and apparently further drafts in the following year were only avoided, by transferring the head-quarters of one of the companies to the home establishment, and absorbing the men in the others. Four of the companies were still in the West Indies, when the amalgamation took place.

Certain details connected with the organization of the Irish Artillery, immediately prior to their incorporation with the Royal Artillery, remain to be mentioned. On the 19th September, 1798, Lord Carhampton, then Master-General of the Irish Ordnance, notified to the officer commanding the corps, that the formation of the Artillery in Ireland into Brigades had been decided upon; the Brigades to be distinguished as heavy and light. The establishment of a Heavy Brigade was to include four medium 12-pounders, and two 5½-inch howitzers: – of a Light Brigade, four light 6-pounder Battalion guns. The former was to be manned by forty-eight non-commissioned officers and men, the latter by thirty-seven – of the Regiment; while the guns and waggons were to be horsed and driven by the Driver Corps. This improved organization superseded the system of Battalion guns; for while, in September, 1798, one hundred of the Irish Artillery were returned as being attached to these, in November only thirty-seven were so employed; in the following January, only four; and in March, 1799, all were finally withdrawn. The additional gunners from the Militia, who had, at the date of the new organization, been 213 in number, were gradually reduced by its operation, and in the monthly return for September, 1799, they disappear altogether.

It was at first proposed that the 12-pounders and the howitzers of the Heavy Brigades should be drawn by four horses, and the 6-pounders of the Light Brigades by three; but subsequently a 4½-inch howitzer having been added to each Light Brigade, the number of horses to each gun was apparently increased from three to four, and the total number of horses to each Heavy Brigade was seventy-three; – to each Light Brigade, fifty-one. The "two leading horses were ridden by Artillerymen, and the gun was driven by a driver."16 This arrangement applied also to the ammunition waggons. The harness-maker, wheeler, and smith, each rode a spare horse with harness on.

While the guns had four horses, the howitzers in Heavy Brigades had but three, and in Light Brigades only a pair. The Driver Corps furnished to each Heavy Brigade 1 officer, 1 quartermaster, 3 non-commissioned officers, and 26 privates; to each Light Brigade, 5 non-commissioned officers and 14 privates. For the information of the general reader, it may be stated that the Brigades of the Irish Artillery were analogous to the present Field Batteries; the modern Brigade of Artillery meaning a number of Batteries linked together for administrative purposes.

In January, 1799, there were twenty-five Brigades in Ireland, and at this point they remained until the amalgamation with the Royal Artillery. Although it is not probable that they were all horsed at that date, there were no less than 1027 officers and men at the appointed stations of the Brigades, and in the language of an old document in the Royal Artillery Record Office, "the New Irish Field Artillery had not only form, but consistency."

In addition to these Brigades of Field Artillery, the Regiment was divided into detachments – generally eight in number, – stationed in the chief harbours, garrisons, and forts, for service with heavy ordnance. The invalid company was scattered over the country, many of the non-commissioned officers and men being totally unfit for service. The Regiment was actively employed in the field during the Rebellion; "and it must be recorded to the honour of the Royal Irish Regiment of Artillery, that though exposed to every machination of the disaffected, and to the strongest temptations, they preserved throughout an unsullied character, and manifested on all occasions a true spirit of loyalty, zeal, and fidelity to His Majesty's service and Government."17

The dress of the Royal Irish Artillery was as follows: – Blue coat with scarlet facings, cuff and collar gold embroidered; yellow worsted lace being used for all beneath the rank of corporal; gold-laced cocked hat, black leather cockade, white cloth breeches, with short gaiters and white stockings in summer, and long gaiters in winter. The non-commissioned officers and men wore their hair powdered and clubbed. In 1798 jackets were introduced according to the pattern adopted for the Army; and the gold lace was removed from the cocked hats.

At the date of the amalgamation the Regiment was armed with cavalry carbines, – the bayonet and pouch, containing from sixteen to eighteen rounds, being carried on the same belt. A cross belt was also worn to which the great-coat was suspended, resting on the left hip. At an earlier period, the Regiment had been armed with long Queen Anne's fusils, which were replaced, when worn out, by arms of various patterns, until at length the cavalry carbine was adopted.

One cannot but be struck – in studying the history of this national corps of Artillery – with the rapidity of its formation, and its attainment of high discipline and professional knowledge, – keeping pace in its career of half a century with the constant changes, with which even in those days this arm was harassed; nor can one read without pride and interest those pages of loyalty at home, gallantry on service abroad, and patient endurance under suffering and disease in the West Indies, – at once as fatal as active war, and yet destitute of the excitement which in war enables the soldier willingly to undergo any hardship.

CHAPTER XV.

First Battalion. – The History and Present Designation of the Companies

In the beginning of the year 1757, the Regiment consisted of nineteen companies, with four field officers. On the 2nd April four additional companies were added, giving a total of twenty-four companies, inclusive of the Cadet Company.

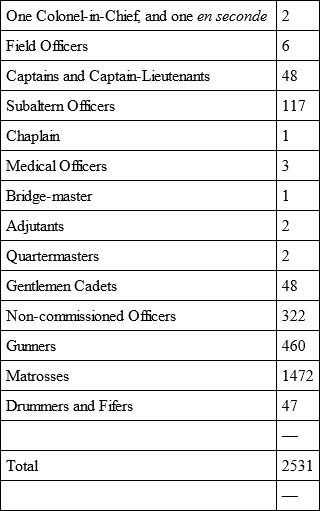

But there was no organization in existence corresponding to the Battalion, or present Brigade, system. The number of company officers was very great, being no less than 140 at the end of 1756; and as there were only four field officers, the prospect of promotion to the younger men was very disheartening. By introducing the Battalion system, and dividing the companies in some way which should give an excuse for an augmentation in the higher ranks, stagnation would be less immediate, and discontent among the junior ranks postponed. Charles, Duke of Marlborough, being then Master-General, approved of this change, and the Regiment was on the 1st August, 1757, divided into two Battalions, each having three field officers, and a separate staff. The strength of the Regiment, after this change had been introduced, was as follows: —

No. of Companies, 24: —

The recruiting of Battalions was always carried on by means of parties scattered over England and Scotland, but the men so obtained were liable to be transferred to other Battalions, whose wants might be greater. This system, which still obtains, prevents, and perhaps wisely, any great Battalion, or Brigade esprit de corps. The real esprit should be for the Regiment first, and then for the Battery. The organization, by whatever name it may be called, which links a certain number of Batteries together for special purposes, has never been allowed the official respect which is paid to the Battalion system in the Infantry. In the absence of such respect, and in the knowledge that the men who might receive their instruction in one Brigade or Battalion were liable to transfer to another, immediately on the completion of their drills, is to be found the reason why both in the days of Battalions and Brigades there has been no esprit found strong enough to weaken that which should exist in every Artilleryman's mind for his Regiment at large, instead of for a detail of it. At the same time, the transfer system can be carried to an injurious extent. The instruction of recruits is more likely to be thorough, if the instructor feels that he himself is likely to retain under his command those whom he educates. The consciousness that the "Sic vos non vobis" system is to be applied to himself must diminish to a certain extent his zeal in instruction. And therefore while no one should be allowed to imagine that his own Battery or his own Brigade is to be considered before the Regiment at large, there can be no doubt that the Depôt system for feeding the Regimental wants is far less cruel than that by which volunteers are called, or transfers ordered, from one portion of the Regiment to another.

The establishment of the 1st Battalion varied very much with the signs of the times. Before the Peninsular War, its greatest strength was in 1758, the year after its formation, when it consisted of 13 companies, and a total of 1383 of all ranks. In 1772, it fell to 8 companies, with a total of 437; but during the American War of Independence, it reached a total of 1259, divided into 11 companies. After the peace of 1783, it was again reduced, falling to a total of 648, in ten companies. During the Peninsular War, the average strength of the Battalion was 1420, the number of companies remaining the same; but as only one company of the Battalion served in the Peninsula, its increased numbers were evidently intended to assist in feeding the companies of other Battalions. After Waterloo it was greatly reduced, and for the next thirty years, its average strength was 700, in 8 companies. In 1846, it rose to a total of 842, and on the outbreak of the War with Russia, in which no fewer than five companies of the Battalion were engaged, further augmentations took place, the totals standing during the war as follows: in 1854, 1208; in 1855, 1336; and in 1856, 1468.

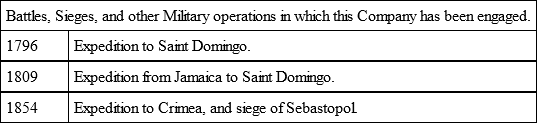

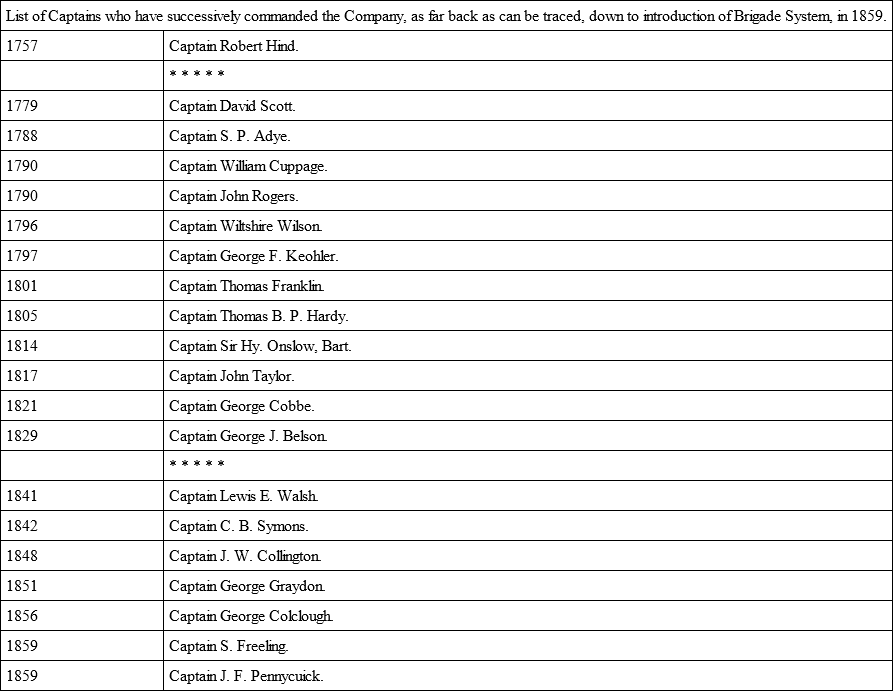

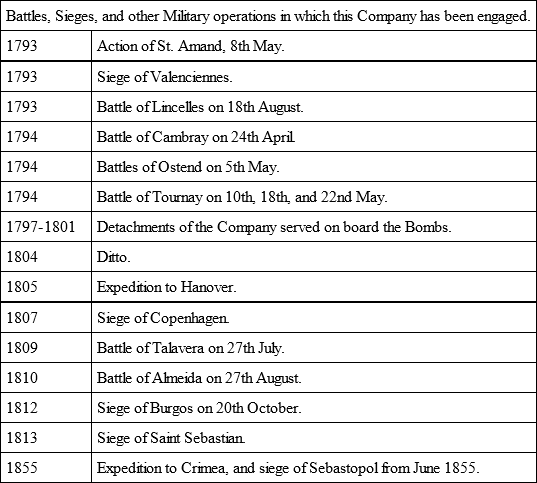

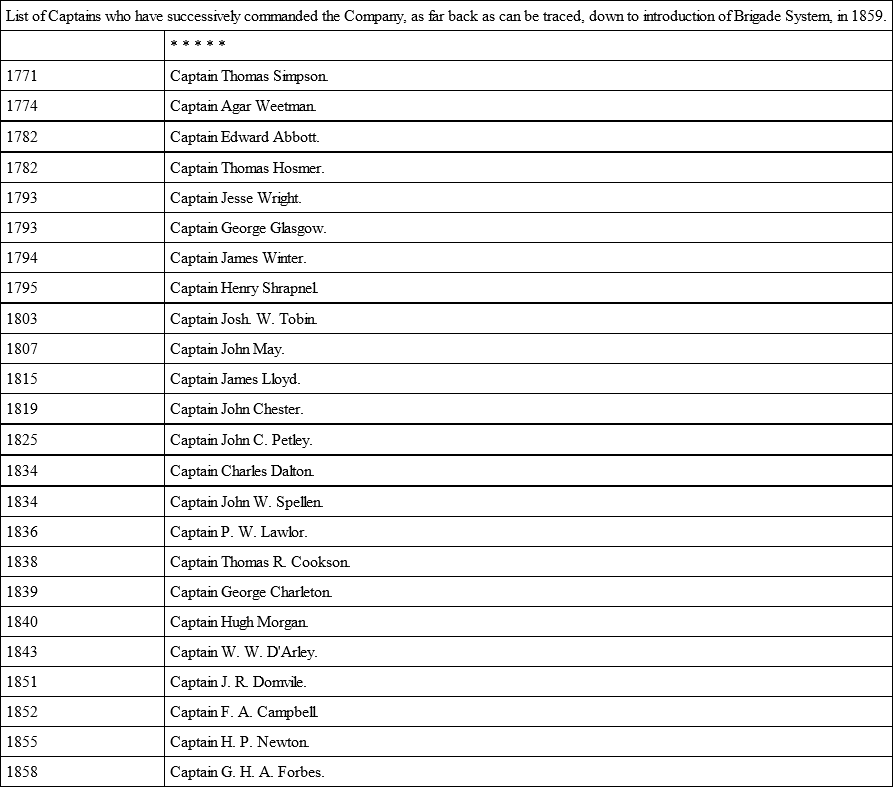

The names of the various Captains who have successively commanded the companies of the 1st Battalion, down to the introduction of the Brigade system, and the new nomenclature in 1859, are given in the following pages, as far as the state of the Battalion Records will admit. The list of the various military operations in which they were severally engaged is also given; and the names which the companies received at the reorganization referred to. It has been thought advisable to give this now in a short but complete form, but in studying the various campaigns, the services of the companies alluded to will occasionally receive more detailed notice.

It is to be remembered that the history of these companies is the legitimate property of the Batteries, which represent them. It is hoped that the publication of their antecedents in this way will not merely interest those in any way connected with them, but will create a feeling of pride which will materially aid discipline, and check negligence. It is believed that with such a past to appeal to as many of the Batteries will find they have, a commander will find a weapon in dealing with his men more powerful than the most penal code, for in each line there seems to be a voice speaking from the dead, and urging those who are, to be worthy of those who have been.

No. 1 COMPANY, 1st BATTALION,

Now "F" BATTERY, 9th BRIGADE.

No. 2 COMPANY, 1st BATTALION,

Now "B" BATTERY, 1st BRIGADE.

No. 3 COMPANY, 1st BATTALION,