полная версия

полная версияHistory of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, Vol. 1

Louisbourg and Quebec – two words – yet on Wolfe's grave they would mean pages of heroism.

CHAPTER XIX.

Minden, – and after Minden

Certain Goths and Vandals, connected with the Board of Ordnance in 1799, issued an order granting permission for the destruction of many old documents which had accumulated in the Battalion offices at Woolwich since the year 1758. Had these been vouchers for pecuniary outlay, it is but just to the Honourable Board to say that this permission would never have been granted. But as they referred merely to such trumpery matters as expenditure of life, and the stories of England's military operations, no reluctance was displayed, nor any trouble taken to distinguish between what might have proved useful, and useless to posterity. A gap consequently occurs in the official records of the 1st and 2nd Battalions, which increases twentyfold the labours of the student.

The Battle of Minden was fought during the years represented by that gap, and the difficulties to be overcome in tracing the identical companies of the Royal Artillery which were engaged can only be realised by the reader, who has himself had to burrow among old records and mutilated volumes. The main purpose in this history being to strengthen the Battery as well as the Regimental esprit, it was of the utmost importance that the Companies, which did so much to decide the contest on that eventful day, should be discovered with certainty, for the sake of the existing Batteries who are entitled to their glory, by virtue of succession; and – to make certain that no hasty conclusions have been arrived at – it has been thought desirable to give the data on which they have been based.

Minden was fought in 1759. Fortunately, a fresh distribution of the companies in the two existing Battalions took place in the preceding year; and the names of the officers in each company are given at length in Cleaveland's MS. notes.

Now three companies are known to have been present at Minden. Of one, Captain Phillips', there is fortunately no doubt. It was then No. 5 Company of the 1st Battalion; and after long and glorious service became on the 1st July, 1859, No. 7 Battery, 14th Brigade, when that change in the nomenclature of the companies took place, which is always baffling the student. On the 1st January, 1860, the exigencies of the service required yet another christening, and it became, on transfer, No. 4 Battery of the 13th Brigade, which it now is. This Battery was undoubtedly present at Minden.

The tracing of the other two companies is not so easy. It is on record that one was commanded by Captain Cleaveland. In 1758, this officer was in command of No. 2 Company of the 2nd Battalion, but in the winter of that year he exchanged with Captain Tovey, of the 1st Battalion, and almost immediately marched with his new company to join the Allied Armies on the Continent. This was then No. 4 Company of the 1st Battalion; and as Captain Cleaveland exchanged into it on the 30th October, 1758, and was in Germany with his Company in the beginning of December, (no second exchange having taken place,) there can be little doubt that another of the Companies at Minden was No. 4 Company of the 1st Battalion, now designated No. 3 Battery of the 5th Brigade.

Judging from a mention of Captain Drummond in one of Prince Ferdinand's despatches, the third company present at the battle would at first sight appear to have been No. 6 of the 2nd Battalion, commanded by Captain Thomas Smith, – Captain Drummond being at that date his Captain-Lieutenant. But there is no mention of Captain Smith in any of the despatches; and as there is a very frequent and most honourable mention of Captain Forbes Macbean, who was undoubtedly present in command of one of the companies, it would appear that Captain-Lieutenant Drummond must have been transferred to some other company for this service. Fortunately the Records of the 1st Battalion – generally a wilderness at this time – contain a key to the solution of the difficulty, for they show that Captain Forbes Macbean (on his promotion on 1st January, 1759, the very year that Minden was fought) took command of No. 8 Company of the 1st Battalion, now A Battery, 11th Brigade. As he never exchanged, and is specially mentioned as having taken his company to Germany, this may be assumed with certainty to have been the third of the companies present at Minden.

A little confusion has been caused by the mention of Captain Foy in Prince Ferdinand's General Order after the battle; and one writer, generally marvellously accurate, assumes that he commanded one of the companies engaged. But, in the first place, he was then merely a Captain-Lieutenant, and much junior even to Captain Drummond, and, in the second, he was then holding a special appointment, namely, that of Bridge-master to the Artillery. Although he and Captain Drummond had undoubtedly each charge of some guns during the battle, he was certainly not there with his Company. Indeed, in a contemporary notice, we find that this officer proceeded alone to join the Allied Army in the capacity named above. He held a similar appointment in America afterwards for nine years, and died in that country in 1779.

The two most prominent of the Artillery officers present at Minden were Captain Phillips, who commanded, and Captain Macbean; and both deserve more than passing notice. The former joined the Regiment as a cadet gunner in 1746, became Lieutenant-Fireworker in the following year, Second Lieutenant in 1755, and First Lieutenant in 1756. When holding this rank, he was appointed to the command of a company of miners raised in 1756 for duty in Minorca, but no longer required after the capitulation of Port Mahon. Instead of disbanding them, however, the Board of Ordnance converted them into a company of Artillery, and added them to the Regiment. Greatly to the indignation of the officers of a corps, whose promotion then, as now, was by seniority, Lieutenant Phillips was transferred with the company, as a Captain, without having passed through the intermediate grade of Captain-Lieutenant. If the end ever justifies the means, this job on the part of Sir John Ligonier, then Lieutenant-General of the Ordnance, was justified by Captain Phillips' subsequent career both in Germany and in America. A minor point in connection with this officer is worthy of mention. He was the first to originate a band in the Royal Artillery – not a permanent one, however – the present Band only dating as far back as 1771, when the 4th Battalion was formed, and with it the nucleus of what has developed into probably the best military band in the world. Captain Phillips died – a general officer – in Virginia, in the year 1781, from illness contracted on active service.

Forbes Macbean, the next most worthy of mention, began his career in the Regiment, as a Cadet Matross, and died in 1800 as Colonel-Commandant of the Invalid Battalion. He was present at Fontenoy, as has already been mentioned; in Germany during the campaign of which Minden was part; in Portugal, where he reached the rank of Inspector-General of the Portuguese Artillery; and in Canada, in the years 1778-9, as commanding the Royal Artillery. He is mentioned in Kane's List, as having been the second officer in the Regiment who obtained the blue ribbon of Science, the Fellowship of the Royal Society – an honour borne by a good many in the Regiment now, and valued by every one who appreciates its position as a scientific corps.

The battle of Minden was the first during the operations in Germany of the Allied Army under Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick, at which special notice was made of the English troops.

These operations commenced in 1757, the year in which Prince Ferdinand assumed the command of the Allied Army, and terminated in 1762. On the 8th March, 1758, Prince Ferdinand captured Minden from the French – a town situated on the river Weser, about 45 miles W.S.W. from Hanover; and retained possession of it until July, 1759, when it was retaken from General Zastrow and his Hessian troops by the French under M. de Broglio.

During this interval, however, the Allied Army had been strengthened by the arrival of the following Regiments from England, sent by King George, as Elector of Brunswick-Luneberg, viz., Cavalry: Horse Guards Blue, Bland's, Howard's, Inniskillen, and Mordaunt's. Infantry: Napier's, Kingsley's, Welsh Fusiliers, Home's, and Stuart's.

These were afterwards joined by the North British Dragoons, and Brudenel's Regiment of Foot. The Artillery which first accompanied this force consisted of a Captain, six subalterns, and 120 non-commissioned officers and men, but in 1759 it was reinforced to a total strength of three companies. At first nothing but light 6-pounders had come, for use as battalion guns, and had this state of matters remained unaltered, this chapter need never have been written. But with the reinforcements of 1759 came also twenty-eight guns of heavier calibre, and the Artillery was now divided into independent Brigades or Batteries, with a proportion merely of battalion guns; and as it now ceased to march in one column, as had formerly been the case, the great kettledrums were no longer carried with the companies.

In July, 1759, the French re-occupied Minden; and, outside the town, Prince Ferdinand was encamped with his Army, the right resting on Minden Marsh, the left on the Weser, but on a somewhat extended arc, and with intervals so great as to appear dangerous. He resolved to make a stand against the French, who had been considerably strengthened and were now under the command of M. de Contades. The French Commander had obtained permission from Paris to attack the Allies, and on the evening of the 31st July he issued the most detailed orders to his army as to the hours of movement, disposition of the troops, and order of battle. Prince Ferdinand anticipating the movements of the French, had issued orders for his army to march at 5 A.M. on the morning of the 1st August, moving in eight columns towards Minden, thus narrowing the arc on which they would deploy, and proportionately diminishing the intervals. By the hour the Allies marched, the French, who had moved two hours before, were drawn up in order of battle, and at 6.30 A.M. the Allied Army was similarly formed. The appearance of the armies now was that of the arcs of two concentric circles, Minden being the centre, and the French Army being on the inner and smaller arc. The French had confidence in superior numbers – in the protection of the guns of the fortress in case of retreat – and in the prestige of recent successes. Their commander had boasted of his intention of surrounding Prince Ferdinand's army, and sending their capitulation to Paris. His plan was to make a powerful attack on General Wangenheim's corps, the left of the Allied Army, and somewhat detached from the main body; which he hoped to turn. But, as the event turned out, Wangenheim's division did not change its position during the whole engagement. About 7 A.M. a French battery commenced harassing the English Artillery, as it advanced in column of route on right of the Allied infantry; but as soon as possible Captain Macbean brought his battery – known as the heavy brigade – into action, and soon silenced the enemy's fire. Although he had only ten medium 12-pounders, manned by his own and Captain Phillips's companies – and two of these were disabled during this Artillery duel – he succeeded in overcoming a battery of thirty guns. While he was thus engaged, the celebrated attack of the British infantry on the French cavalry was taking place. The British, accompanied by the Hanoverian Guards, and Hardenberg's Regiment, marched for some 150 paces, exposed both to a cross fire from the enemy's batteries, and a musketry fire from the infantry; but, notwithstanding their consequent losses, and their continued exposure on both flanks, so unshaken were they, and so courageously did they fight, that in a very short time the French cavalry was routed. It is doubtful if their gallantry has ever been exceeded. Captain Macbean, being now at leisure, advanced his battery, came into action to the left, and – first preventing the French cavalry from reforming – followed by opening fire upon the Saxon troops who were now attacking the British infantry. The value of this assistance was very great.

On the left of the Allies, the Artillery fire was equally successful, and the Hanoverians and Hessians greatly distinguished themselves. Notwithstanding the unhappy and severely expiated blunder of Lord George Sackville, in failing to obey the orders for advancing his cavalry, before 10 A.M. the French army fled in confusion. At this time, Prince Ferdinand advanced the English guns on the right, as close to the morass as they could be taken, to prevent the French from returning to their old camp on the Minden side of Dutzen; and in this he completely succeeded, – the enemy being compelled to retire behind the high ground, with their right on the Weser. The victorious army encamped on the field of battle, and on totalling their losses, they were found to amount to 2800 killed and wounded, 1394 of that number being British. The French lost in killed, wounded, and prisoners, between 7000 and 8000; besides 43 cannon, 10 pairs of colours, and 7 standards.

The Royal Artillery had present on this memorable day in addition to Captain Macbean's heavy brigade, two light 12-pounders, three light 6-pounders, and four howitzers, under Captain-Lieutenant Drummond; and four light 12-pounders, three light 6-pounders, and two howitzers, under Captain-Lieutenant Foy. There were also twelve light 6-pounders with six British battalions. Captain Phillips commanded the whole three companies at the battle.

The two points which strike one most after the perusal of the accounts of this engagement are the stolidity and nerve of English infantry under fire, and the advantage of independent action on the part of Field Artillery.

Minden was a cruel blow at the system of battalion guns. And although battalion guns have long disappeared, the mere concentration of them into batteries was not enough, while those batteries had to accommodate their movements to those of the battalions to which they were attached. Billed ordnance – with a range double that of the infantry weapon – had been in existence for years; and yet general officers at reviews and field-days made the batteries keep with the battalions; – advancing, retiring, dressing together, as if the only advantage of a gun over a rifle was the size of the projectile, and not also increased range. It seemed never to dawn upon their understanding that by bringing their Artillery within range of the enemy's infantry fire, as by their system they certainly did, they would ensure for their batteries, after half an hour's engagement, a ghastly paraphernalia of dead horses and empty saddles. It was not until the year 1871, that an order was issued by one who is at once Commander-in-Chief of the Army, and Colonel of the Royal Artillery, giving to field batteries in the field that inestimable boon, comparative freedom of action. The lesson was a long time in learning; and one of the best teachers was one of the oldest – this very Battle of Minden – which, in the words of one who took part in it, was of such importance in its results, that it "entirely defeated the French views, disconcerted all their schemes, and rescued Hanover, Brunswick, and Hesse from the rapacious hands of a cruel ambitious, and elated enemy."

On the day after the battle, Prince Ferdinand issued a General Order, thanking the army for their gallantry, and particularizing, among others, "the three English Captains, Phillips, Drummond, and Foy;" and on discovering that he had omitted mention of Captain Macbean, he wrote the following letter to him in his own hand.

"To Captain Macbean, of the British Artillery.

"Sir, – It is from a sense of your merit, and a regard to justice, that I do in this manner declare I have reason to be infinitely satisfied with your behaviour, activity, and zeal, which in so conspicuous a manner you made appear at the battle of Thonhausen, on the 1st of August. The talents you possess in your profession did not a little contribute to render our fire superior to that of the enemy, and it is to you and your Brigade that I am indebted for having silenced the fire of a battery of the enemy, which extremely galled the troops, and particularly the British infantry.

"Accept then, sir, from me the just tribute of my most perfect acknowledgment, accompanied by my most sincere thanks. I shall be happy in every opportunity of obliging you, desiring only occasions of proving it; being with the most distinguished esteem,

"Your devoted and entirely affectionate servant,

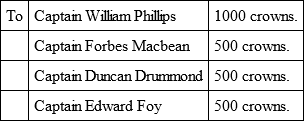

(Signed) "Ferdinand,"Duke of Brunswic and Luneberg."Subsequently, as a further proof of his appreciation of the services of the Royal Artillery at Minden or Thonhausen, as the battle was also named, the Prince directed the following gratuities to be presented to the senior officers: —

The story of the remaining operations of the Allied Army, in so far as they bear upon the services of the Royal Artillery, may be briefly stated. In 1760, two additional companies were sent to Germany, the Regiment having in the interim been augmented by a third battalion. The British guns now with the army were as follows: – eight heavy, twelve medium, and six light 12-pounders; thirty light 6-pounders; three 8-inch, and six Royal mortars. Before the end of the war the armament was changed to eight heavy, six medium, and four light 12-pounders; twenty-four heavy, and thirty-four light 6-pounders; eight 8-inch, and four Royal howitzers. Captain Macbean is the prominent Artillery officer during the rest of the campaign: except, perhaps, at Warberg, where, on the 30th July, 1760, Captain Phillips astounded every one by bringing up the Artillery at a gallop, and so seconding the attack as utterly to prevent the enemy, who had passed the Dymel, from forming on the other side; and by the accuracy and rapidity of his fire, converting their retreat into a precipitate rout. Perhaps it was young blood that prompted this unexpected action; for, as has already been stated, he was but a boy compared with most captains; if so, it contributes somewhat to atone for Sir John Ligonier's favouritism. More than thirty years were to pass before Horse Artillery should form part of the British army, and show what mobility it was possible to attain; and more than a century ere Field Artillery should reach the perfection it now possesses, a perfection which treads closely on the heels of the more brilliant branch. During the Seven Years' War, so unwieldy was the movement of Artillery in the field, that this little episode, which makes modern lips smile, was thought worthy of a record denied to events which would now be considered far more important.

Although more than two years passed between the Battle of Minden and the conclusion of peace, the custom which then prevailed of armies going into winter-quarters curtailed the time for active operations; and even when the forces were manœuvring, much of the time was spent in empty marching and counter-marching. At Warberg, as at Minden, the heaviest loss fell upon the English troops, of whom 590 were killed or wounded; their gallantry – more especially in the case of the Highlanders and grenadiers – being again conspicuous. Among the trophies taken on this occasion from the enemy were ten guns.

The fortune of war changed repeatedly; and the British troops received further reinforcements, including three battalions of the Guards. Lord George Sackville having been cashiered was succeeded in the command of the English contingent by the Marquis of Granby; and a cheerful feeling prevailed among the troops, since the news had arrived of the conquest of Canada.

On the 12th February, 1761, Captain Macbean received the brevet rank of Major, and was ordered to proceed with a brigade of eight heavy 12-pounders, to join the Hereditary Prince near Fritzlar, on the following day. This town was garrisoned by 1200 French troops under M. de Narbonne; and Major Macbean – having been entrusted with the command of the whole Artillery of the Prince's army – commenced the bombardment on the 14th, placing his batteries within 300 yards of the wall, and advancing some light pieces even nearer, to scour the parapet with grape. As, however, he had no guns heavier than 12-pounders, and the walls were made of flint, his fire, although hot and steady, made little or no impression; nor could he do much damage to the gates, which were barricaded with felled trees, and immense heaps of earth and stones.

The Hereditary Prince, although expressing himself pleased with Major Macbean's dispositions, was evidently impatient to take the city; so Major Macbean suggested shelling it with howitzers, a suggestion which was approved of. So successful was the fire, that in about an hour's time the enemy capitulated, being allowed to march out with the honours of war.

Major Macbean received the Prince's special thanks; and the town was ordered to pay him 4000 crowns in lieu of their bells, a perquisite in those days of the commanding officer of Artillery, when a siege was crowned with success.

From this time, matters looked well for the Allies. On the 25th June, 1761, news reached the army of the reduction of Belleisle; and in October, 1762, tidings of the British successes at the Havannah arrived. On both occasions, a feu de joie was fired. On the 1st November, 1762, Cassel capitulated; a signal victory was gained over the combined Austrians and Imperialists, near Freytag, by Prince Henry of Prussia, which filled the Allied camp with joy; and on the 14th November, word reached the army that the preliminaries of peace had been signed at Fontainebleau. On the 24th December, Prince Ferdinand wrote to King George, congratulating him on the peace, and asking permission to quit the army, where his presence was no longer necessary; and at the same time he announced to the British troops, that the remembrance of their gallantry would not cease but with his life; and that "by the skill of their officers he had been enabled at the same time to serve his country, and to make a suitable return for the confidence which His Britannic Majesty had been pleased to honour him with."

On the 13th January, 1763, the thanks of the House of Commons was conveyed to the British troops for "their meritorious and eminent services;" and on the 25th January, their homeward march through Holland commenced; through the provinces of Guelderland, Nimeguen, and Breda, to Williamstadt, where they took ship for England.

And, as sleep on the eyes of the weary, so peace descended for a time on those towns and hamlets by the Weser and the Rhine, which had been for so many years unwilling pawns on the great chess-board of war.

CHAPTER XX.

The Third Battalion. – The History and Present Designationof the Companies

Not very long after the Battle of Minden, and while the lessons of the war were urging on the military world the increasing importance of Artillery, the Board of Ordnance resolved to increase the Royal Artillery still further. This was done by transferring five companies from the existing battalions, and by raising five others; the ten being combined into the Third Battalion with a staff similar to that of the other two. Each company of the battalion consisted of a Captain, a Captain-Lieutenant, a First and Second Lieutenant, 3 Lieutenant-Fireworkers, 3 sergeants, 3 corporals, 8 bombardiers, 20 gunners, 62 matrosses, and 2 drummers; making a total of 105 per company.

The total of all ranks, on the formation of the battalion, was 1054. At the end of the Seven Years' War, the battalion was reduced to 554; but as the troubles in America became visible, it was again increased; and in 1779, the establishment of all ranks stood at 1145. At the peace of 1783, it fell to 648; rising, however, in 1793, during England's continental troubles, to 1240. It reached its maximum during the Peninsular War, when its strength was no less than 1461 of all ranks. In the year 1778, when the 4th Battalion was raised, two companies were taken from the 3rd; but they were replaced in 1779.

For thirty years after the reductions made in 1816, the average strength of the battalion was 700; but from that time it gradually rose until, at the commencement of the war with Russia, it stood at 1128, and in the following year it reached 1220.