полная версия

полная версияHistory of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, Vol. 1

March 30, 1750. "The Sergeant of the Guard is not to suffer any non-commissioned officer or private man to go out of the Warren gate unless they are dressed clean, their hair combed and tied up, with clean stockings, and shoes well blacked, and in every other respect like soldiers. The cooks are excepted during their cooking hours, but not otherwise."

May 9, 1750. "No subaltern officer is for the future to have a servant out of any of the companies."

July 17, 1750. "The commanding officers of companies are ordered by the general to provide proper wigs for such of their respective men that do not wear their hair, as soon as possible."

July 25, 1750. "Each company is to be divided into three squads. The officers and non-commissioned officers to be appointed to them to be answerable that the arms, accoutrements, &c., are kept in constant good order, and that the men always appear clean."

July 25, 1750. "Joseph Spiers, gunner in Captain Desagulier's company, is by sentence of a Court-martial broke to a matross, and to receive 100 lashes; but General Borgard has been pleased to forgive him the punishment."

A General Court-martial was ordered to assemble at the Academy to try a matross for desertion. The Court, which assembled at 10 A.M. on the 20th October, 1750, was composed of Lieutenant-Colonel Belford as President, with nine captains and three lieutenants as members.

November 3, 1750. "Sergeant Campbell, in Captain Pattison's company, is by sentence of a Regimental Court-martial reduced to a Bombardier for one month, from the date hereof, and the difference of his pay to be stopped."

The death of General Borgard took place in 1751, and he was succeeded by Colonel Belford. This officer was most energetic in drilling officers and men, and in compelling them to attend Academy and all other instructions. Even such an opportunity as the daily relief of the Warren guard was turned to account by him; and the old and new guards were formed into a company for an hour's drill, under the senior officer present, at guard mounting. From one order issued by him, it would seem as if the authority of the captains required support, being somewhat weakened perhaps, as is often the case, by the oversight and interference in small matters by the colonel; for we find it was necessary on March 2, 1751, to order "That when any of the Captains review their companies either with or without arms, all the officers belonging to them were to be present."

Colonel Belford's weakness for the carbine is apparent in many of his orders.

April 1, 1751. "All the officers' servants who are awkward at the exercise of the small arms to be out every afternoon with the awkward men, and the rest of them to attend the exercise of the gun."

A most important official must have been expected in the Warren on the 5th August, 1751, for we find orders issued on the previous evening, as follows:

"The Regiment to be under arms to-morrow morning at nine o'clock. The commanding officers are to see that their respective men are extremely well-powdered, and as clean as possible in every respect. The guard to consist to-morrow of one Captain, two Lieutenants, two Sergeants, four Corporals, and forty men. The forty men are to consist of ten of the handsomest fellows in each of the companies. The Sergeant of the Guard to-morrow morning is not to suffer anybody into the Warren but such as shall appear like gentlemen and ladies."

February 7, 1752. "For the future when any man is discharged he is not to take his coat or hat with him, unless he has worn them a year."

April 6, 1752. "The officer of the Guard is for the future to send a patrol through the town at any time he pleases between half an hour after ten at night and one in the morning, with orders to the Corporal to bring prisoners all the men of the Regiment he finds straggling in the streets. The Corporal is likewise to inspect all the alehouses, where there are lights, and if there are any of the men drinking in such houses, they are also to be brought to the Guard; but the patrol is by no means to interfere with riot or anything that may happen among the town-people."

April 20, 1752. "When any man is to be whipped by sentence of a court-martial, the Surgeon, or his Mate, is to attend the punishment."

February 6, 1753. "The officers are to appear in Regimental hats under arms, and no others."

February 19, 1753. "The officers appointed to inspect the several squads are to review them once every week for the future; to see that every man has four good shirts, four stocks, four pair of stockings, two pair of white, and one pair of black spatterdashes, two pair of shoes, &c.; and that their arms, accoutrements, and clothes are in the best order. What may be required to complete the above number is to be reported to the commanding officer and the Captains. The officers are likewise to see that the men of their squads always appear clean and well-dressed like soldiers; and acquaint their Captains when they intend to review them."

February 20, 1753. "The Captains are to give directions to their Paymasters to see that the initial letters of every man's name are marked with ink in the collar of their shirts."

April 5, 1753. "The Captains or commanding officers of companies are not to give leave of absence to any of their recruits or awkward men."

April 29, 1753. "It is Colonel Belford's positive orders that for the future, either the Surgeon or his Mate always remain in quarters."

May 23, 1753. "No non-commissioned officer or private man to appear with ruffles under arms."

June 15, 1753. "No man to be enlisted for the future who is not full five feet nine inches without shoes, straight limbed, of a good appearance, and not exceeding twenty-five years of age."

January 2, 1754. "No officer to appear under arms in a bob-wig for the future."

October 19, 1754. "When any of the men are furnished with necessaries, their Paymasters are immediately to give them account in writing of what each article cost."

October 28, 1754. No Cadet is for the future to take any leave of absence but by Sir John Ligonier, or the commanding officer in quarters."

November 8, 1754. "In order that the sick may have proper airing, one of the orderly Corporals is every day, at such an hour as the Surgeon shall think proper, to collect all those in the Infirmary who may require airing, and when he has sufficiently walked them about the Warren, he is to see them safe into the Infirmary. If any sick man is seen out at any other time, they will be punished for disobedience of orders."

March 17, 1755. "All officers promoted, and those who are newly appointed, are to wait on Colonel Belford with their commissions as soon as they receive them."

July 20, 1755. "If any orderly or other non-commissioned officer shall excuse any man from duty or exercise without his officer's leave, he will be immediately broke."

August 1, 1755. "As there are bomb and fire-ship stores preparing in the Laboratory, the officers who are not acquainted with that service, and not on any other duty, will please to attend, when convenient, for their improvement."

August 8, 1755. "It is ordered that no non-commissioned officer or soldier shall for the future go out of the Warren gate without their hats being well cocked, their hair well-combed, tied, and dressed in a regimental manner, their shoes well blacked, and clean in every respect… And it is recommended to the officers and non-commissioned officers, that if they at any time should meet any of the men drunk, or not dressed as before mentioned, to send them to the Guard to be punished."

February 13, 1756. "The Captains are forthwith to provide their respective companies with a knapsack and haversack each man."

February 16, 1756. "For the future, when any Recruits are brought to the Regiment, they are immediately to be taken to the Colonel or commanding officer for his approbation; as soon as he has approved of them, they are directly to be drawn for, and the officers to whose lot they may fall are forthwith to provide them with good quarters, and they are next day to be put to the exercise."

March 16, 1756. "The Captains are to attend parade morning and afternoon, and to see that the men of their respective companies are dressed like soldiers before they are detached to the guns."

March 30, 1756. "It is recommended to the officers to confine every man they see dirty out of the Warren, or with a bad cocked hat."

March 31, 1756. "The officers are desired not to appear on the parade for the future with hats otherwised cocked than in the Cumberland manner."

April 2, 1756. "It is the Duke of Marlborough's orders that Colonel Belford writes to Captain Pattison to acquaint General Bland that it is His Royal Highness's commands that the Artillery take the right of all Foot on all parades, and likewise of dragoons when dismounted."

May 1, 1756. "It is Colonel Belford's orders that no non-commissioned officer, or private man, is to wear ruffles on their wrists when under arms, or any duty whatsoever for the future."

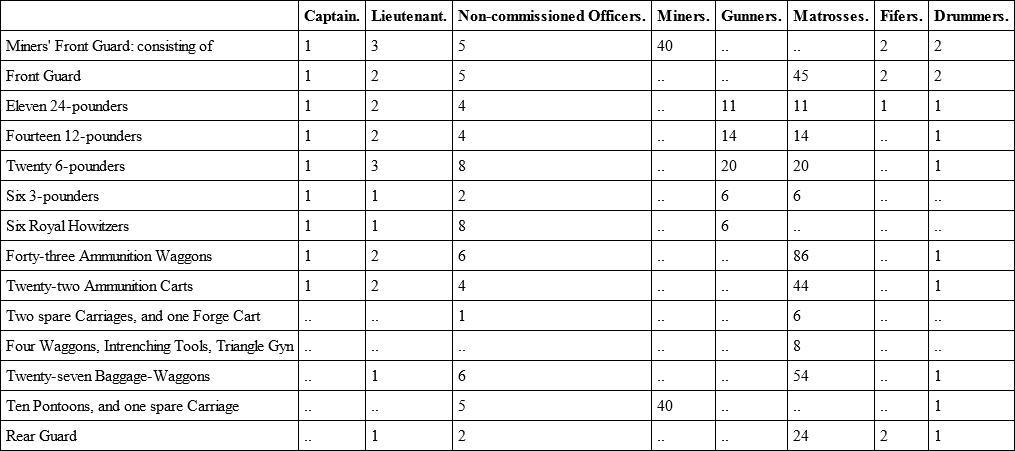

About this time, a camp was ordered to be formed at Byfleet, where the Master-General of the Ordnance was present, and as many of the Royal Artillery as could be spared. Most of the Ordnance for the camp went from the Tower, and the following disposition of the Artillery on the march from London to Byfleet may be found interesting.

Advanced Guard: – Consisting of 1 non-commissioned officer and 12 matrosses.

Giving a total of 29 officers, 61 non-commissioned officers, 57 gunners, 330 matrosses, 80 miners, 7 fifers, and 12 drummers.

This train of Artillery left the Tower in July, and remained in Byfleet until October, practising experiments in mining, and the usual exercises of Ordnance, under the immediate eye of the Master-General himself, the Duke of Marlborough, who marched at the head of the train, and encamped with it. An interesting allusion to a custom long extinct appears in the orders relative to the camp. We find certain artificers detailed for the flag-gun and the flag-waggon. The former was always one of the heaviest in the field; and the custom is mentioned in 1722, 1747, and in India in 1750. Colonel Miller, in alluding to this custom in his valuable pamphlet, expresses his opinion that the flag on the gun corresponded to the Queen's colour, and that on the waggon to the Regimental colour, the latter probably bearing the Ordnance Arms. The guns had been divided into Brigades, corresponding to the modern Batteries. Four 24-pounders, five 12-pounders, five 6-pounders, and six 3-pounders, respectively, constituted a Brigade. The howitzers were in Brigades of three. The discipline insisted upon was very strict. Lights were not allowed even in the sutler's tents after ten o'clock; no man was allowed to go more than a mile from camp without a pass; officers were not allowed to appear in plain clothes upon any occasion; strong guards were mounted in every direction, with most voluminous orders to obey, – orders which seem occasionally unreasonable. The Captain of the Guard had to see the evening gun fired, and was made "answerable for any accident that might happen" – a somewhat heavy responsibility, as accidents are not always within the sphere of control, where the executive officer's duties are placed. Whenever the weather was fine, all the powder was carefully aired, and all articles of equipment requiring repair were laid out for inspection. The powers of the commanding officers of companies in granting indulgences to their men were curtailed. No artificer was allowed to be employed at any time on any service but His Majesty's, without the leave of the Duke of Marlborough himself, or the commandant in the camp; and should any officer excuse a man from parade he was to be put in arrest for disobedience of orders.

Colonel Belford revelled in the discipline of the camp. It brought back to his mind the old days in Flanders when he worked so hard to imbue his men with a strict military spirit, and, with the Master-General by his side, he felt renewed vigour and keenness. The Regiment was attracting greater attention every year; augmentations were continuous. The year before the Byfleet camp was formed, six companies had been added: this year there were three more; and in 1757, four additional companies were to be raised. The King had reviewed the Regiment, and the Duke of Cumberland came to Woolwich every year to inspect and encourage. Who can tell whether the new organization of 1757, which divided the Regiment into Battalions and accelerated the stagnant promotion, did not come from the long days of intercourse at Byfleet between Colonel Belford and the Master-General? The opportunities offered by such a meeting must have been priceless to a man who was so fond of his Regiment. Nothing is so infectious as enthusiasm; and we learn from Colonel Belford's orders and letters that he was an enthusiastic gunner. The early History of the Regiment is marked by the presence in its ranks of men eminent in their own way, and perfectly distinct in character, yet whose talents all worked in the same direction, the welfare of their corps. Who could be more unlike than Borgard and his successor, Colonel Belford? And yet a greater difference is found between the scientific Desaguliers, and the diplomatic and statesmanlike Pattison, the model of a liberal-minded, high-spirited soldier. These four men are the milestones along the road of the Regiment's story from 1716 to 1783. They mark the stages of continuous progress; but there the parallel fails. For they were no stationary emblems. Their whole life was engrossed in their Regiment. To one, discipline was dear; to another, military science; to another, gunnery, and the laboratory; and they drew along with them in the pursuits they loved all those whose privilege it was to serve under them. It was in a small and distinct way a representation of what the Regiment in its present gigantic proportions would be, if the suggestions quoted in the commencement of this volume were heartily adopted by all who belong to it. Out of the faded pages and musty volumes which line the walls of the Regimental Record Office, there seems to come a voice from these grand old masters, "Be worthy of us!" To them, their corps was everything; to its advancement every taste or talent they possessed was devoted. With its increased proportions, there has now come an increased variety of tastes, of learning, and of accomplishments; and the lives of our great predecessors in the corps read like a prayer over the intervening years, beseeching us all to work together for the Regiment's good.

If variety of taste is to produce opposition in working, or dissipation of strength and talent, what a cruel answer the Present gives to the Past! But, if it is to raise the Regiment in the eyes, not merely of military critics, but of that other world of science, across whose threshold not a few Artillerymen have passed with honour, then the variety of tastes working together, and yet independently – conducing to the one great end – is the noblest response that can be made to those who showed us in the Regiment's earliest days how to forget self in a noble esprit de corps.

CHAPTER XIII.

To 1755

A number of interesting events can be compressed into a chapter, covering the period between the end of the war in Flanders and the year 1755.

The dress and equipment of the Regiment underwent a change. In 1748, the last year of the war, the field staffs of the gunners, their powder horns, slings, and swords, and the muskets of the matrosses were laid aside, and both ranks were armed with carbines and bayonets – thus paving the way for the step taken in the year 1783, when the distinction between the two ranks was abolished. The non-commissioned officers retained their halberds until 1754, when they were taken from the corporals and bombardiers, who fell into the ranks with carbines. In 1748, black spatterdashes were introduced into the Regiment, for the first time into any British corps. In 1750, the sergeants' coats were laced round the button-holes with gold looping, the corporals, bombardiers, and the privates having yellow worsted looping in the same way. The corporals and bombardiers had gold and worsted shoulder-knots; the surtouts were laid aside, and complete suits of clothing were issued yearly.14

At the end of the war, the Regiment consisted of ten companies, and for the first time, reliefs of the companies abroad were carried out, those at Gibraltar and Minorca being relieved by companies at Woolwich. The strength of the Regiment remained unchanged until 1755, when six new companies were raised, making a total of sixteen, exclusive of the Cadet company.

The year 1751 was marked by several important Regimental events. The father of the Regiment, old General Borgard, died; and was succeeded by Colonel Belford. The vexed question of the Army rank of Artillery officers was settled by the King issuing a declaration under his Sign-Manual, retrospective in its effects, deciding "the rank of the officers of the Royal Regiment of Artillery to be the same as that of the other officers of his Army of the same rank, notwithstanding their commissions having been hitherto signed by the Master-General, the Lieutenant-General, or the principal officers of the Ordnance, which had been the practice hitherto." From this date all commissions of Artillery officers were signed by the sovereign, and countersigned by the Master-General of the Ordnance.

This year also saw the abolition of an official abuse dating back before the days of the Regiment's existence. Up to this time, all non-commissioned officers, gunners, matrosses, and even drummers, had warrants signed by the Master-General, and countersigned by his secretary, for which a sergeant paid 3l., a matross or drummer, 1l. 10s., and the intermediate grades in proportion.

This was now abolished, with great propriety, as an old MS. says, "as no one purpose appears to have been answered by it, but picking of the men's pockets." Doubtless, there were in the Tower officials who would not endorse this statement; and who were of opinion that a very material purpose was answered by it.

In February of this year, also, the officers of the Regiment entered into an agreement for the establishment of a fund for the benefit of their widows, no such fund having as yet existed. Each officer agreed to subscribe three days' pay annually, and three days' pay on promotion; but this subscription apparently was felt to be too high, or it was considered proper that some assistance should be rendered to the fund by the Government, for in 1762 a Royal Warrant was issued, directing one day's pay to be stopped from each officer for the Widows' Fund, and that one non-effective matross – in other words a paper man – should be mustered in each company, the pay of such to be credited to the fund. By this means it was hoped that the widow of a Colonel Commandant would obtain 50l. per annum; of a Lieutenant-Colonel, 40l.; of a Major, 30l.; of a Captain, 25l.; of a Lieutenant, Chaplain, or Surgeon, 20l.; and of a Lieutenant-Fireworker, 16l. But, either the officers would not marry, or the married officers would not die, for in 1772 another warrant was issued, announcing that the fund was larger than was necessary, and directing the surplus to be given as a contingent to the Captains of companies. It is somewhat anticipating matters, but it may here be said that a few years later the officers of the Regiment again took the matter into their own hands, and formed a marriage society, membership of which was nominally voluntary, but virtually compulsory, until about the year 1850, after which it failed to receive the support of the corps, its rules not being suited to modern ideas. On 13th May, 1872, these rules were abrogated at a public meeting of the officers at Woolwich, and the society, with its accumulated capital of 50,000l., was thrown open on terms sufficiently modern and liberal to tempt all who had hitherto refrained from joining it. At that meeting, the original charter of the society, signed by the officers serving in the Regiment at the time, was submitted to their successors, and there was a dumb eloquence in the faded parchment with its long list of signatures, which it would be impossible to express in words.

It has already been stated that Colonel Pattison and Major Lewis had been permitted to retire on full pay, on account of infirmity. The source from which their income was derived, and the use to which it was devoted after their death, can best be described in Colonel Miller's words: "To this purpose there was appropriated the pay allowed for two tinmen and twenty-four matrosses, the number of effective matrosses being reduced from forty-four to forty in each company, whilst forty-four continued to appear as the nominal strength. At the death of Jonathan Lewis, a warrant dated 25th September, 1751, approved of the non-effectives being still kept up, and directed the sum of 273l. 15s. a year (15s. a day) then available to be applied thus: – 173l. 15s. to Colonel Belford (as colonel commandant), and 100l. to Catherine Borgard, widow of Lieutenant-General Albert Borgard, towards the support of herself and her two children, who were left unprovided for. When Colonel Thomas Pattison died, a warrant dated 27th February, 1753, directed that the annuity to Mrs. Borgard should in future be paid out of another source, and applied the balance of the fund derived from the non-effective tinmen and matrosses to increasing the pay of the fireworkers from 3s. to 3s. 8d. a day."

"In 1763 the increased pay of the fireworkers was entered in the estimates, and the pay of colonel commandant was raised to 2l. 4s. a day."

During the period to which this chapter refers, a review of the Regiment by the King took place in the Green Park; and as it was thought worthy of entry in General Macbean's diary, and shows the way in which the Regiment was formed upon such an occasion, it may not be deemed out of place in this work. There were five companies present besides the Cadets, and the numbers were as follows: – Field officers, three; Captains, five; Captain-Lieutenants, six; four First, and seven Second Lieutenants; Lieutenant-Fireworkers, seventeen; one Chaplain, one Adjutant, one Quartermaster, one Bridge-master, one Surgeon and his Mate, fifteen Sergeants, fifteen Corporals, one Drum-Major, ten Drummers and six Fifers, forty Bombardiers, forty-eight Cadets, ninety-eight Gunners, and 291 Matrosses. The companies were formed up as a Battalion; three light 6-pounders being on the flanks, and the Cadets formed up on the right as a Battalion.

Although there was peace for England in Europe up to 1755, there was no lack of expeditions elsewhere. Besides Jamaica and Virginia, which demanded guns and stores, Artillery was required for the East Indies and America. It was for service in the former country that the augmentation of four companies with an additional Major was made in March, 1755.

They were raised and equipped in thirty days, and embarked immediately, the Board giving permission to Major Chalmers, who was in command, to fill up any vacancies which might occur, by promoting the senior on the spot. These companies were in the pay of the East India Company, and formed part of the expedition under Clive and Admiral Watson. One of the companies was lost on the passage, only three men being saved. It was Captain Hislop's company, but that officer had been promoted while serving in the East Indies, and it was commanded on the voyage by the Captain-Lieutenant, N. Jones. As soon as the disaster was known in England, another company was raised, and on its arrival in India Captain Hislop assumed the command. This officer had gone out with five officers, sixty men, and twelve cadets, and a small train of Artillery, attached to the 39th Regiment, under Colonel Aldercon. His new company was the last of the Royal Artillery which served in Bengal, until the outbreak of the Indian Mutiny.15

The expedition to America was the ill-fated one commanded by General Braddock. The detachment of Royal Artillery was only fifty strong; it left England under the command of Captain-Lieutenant Robert Hind, with two Lieutenants, three Fireworkers, and one cadet; and on its arrival in America was joined by Captain Ord, who assumed the command. This officer had been quartered with his company at Newfoundland; but at the request of the Duke of Cumberland he was chosen to command the Artillery on this expedition. The guns which accompanied the train were ten in number, all light brass guns – four being 12-pounders, and six 6-pounders. The civil attendants of the train were twenty-one in number, including conductors and artificers; and there were attached to the train – attendants not generally found in such lists – "ten servants, and six necessary women." There were also five Engineers, and practitioner Engineers.