полная версия

полная версияThe Classic Myths in English Literature and in Art (2nd ed.) (1911)

Then Aurora, seeing her son's fate, directed his brothers, the Winds, to convey his body to the banks of the river Æsepus in Mysia. In the evening Aurora, accompanied by the Hours and the Pleiads, bewept her son. Night spread the heaven with clouds; all nature mourned for the offspring of the Dawn. The Æthiopians raised his tomb on the banks of the stream in the grove of the Nymphs, and Jupiter caused the sparks and cinders of his funeral pile to be turned into birds, which, dividing into two flocks, fought over the pile till they fell into the flame. Every year at the anniversary of his death they celebrated his obsequies in like manner. Aurora remained inconsolable. The dewdrops are her tears.166

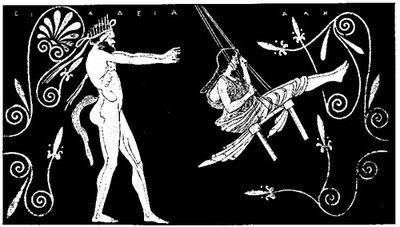

Fig. 101. The Death of Memnon

The kinship of Memnon to the Dawn is certified even after his death. On the banks of the Nile are two colossal statues, one of which is called Memnon's; and it was said that when the first rays of morning fell upon this statue, a sound like the snapping of a harp-string issued therefrom.167

So to the sacred Sun in Memnon's faneSpontaneous concords choired the matin strain;Touched by his orient beam responsive ringsThe living lyre and vibrates all its strings;Accordant aisles the tender tones prolong,And holy echoes swell the adoring song.168CHAPTER XII

MYTHS OF THE LESSER DIVINITIES OF EARTH, ETC

129. Pan, and the Personification of Nature. It was a pleasing trait in the old paganism that it loved to trace in every operation of nature the agency of deity. The imagination of the Greeks peopled the regions of earth and sea with divinities, to whose agency it attributed the phenomena that our philosophy ascribes to the operation of natural law. So Pan, the god of woods and fields,169 whose name seemed to signify all, came to be considered a symbol of the universe and a personification of Nature. "Universal Pan," says Milton in his description of the creation:

Universal Pan,Knit with the Graces and the Hours in dance,Led on the eternal Spring.Later, Pan came to be regarded as a representative of all the Greek gods and of paganism itself. Indeed, according to an early Christian tradition, when the heavenly host announced to the shepherds the birth of Christ, a deep groan, heard through the isles of Greece, told that great Pan was dead, that the dynasty of Olympus was dethroned, and the several deities sent wandering in cold and darkness.

The lonely mountains o'er,And the resounding shore,A voice of weeping heard and loud lament;From haunted spring and dale,Edged with poplar pale,The parting Genius is with sighing sent;With flower-inwoven tresses torn,The nymphs in twilight shade of tangled thickets mourn.170Many a poet has lamented the change. For even if the head did profit for a time by the revolt against the divine prerogative of nature, it is more than possible that the heart lost in due proportion.

His sorrow at this loss of imaginative sympathy among the moderns Wordsworth expresses in the sonnet, already cited, beginning "The world is too much with us." Schiller, also, by his poem, The Gods of Greece, has immortalized his sorrow for the decadence of the ancient mythology.

Fig. 102. Pan Blowing His Pipe, Echo Answering

Ah, the beauteous world while yet ye ruled it, —Yet – by gladsome touches of the hand;Ah, the joyous hearts that still ye governed,Gods of Beauty, ye, of Fable-land!Then, ah, then, the mysteries resplendentTriumphed. – Other was it then, I ween,When thy shrines were odorous with garlands,Thou, of Amathus the queen.Then the gracious veil, of fancy woven,Fell in folds about the fact uncouth;Through the universe life flowed in fullness,What we feel not now was felt in sooth:Man ascribed nobility to Nature,Rendered love unto the earth he trod,Everywhere his eye, illuminated,Saw the footprints of a God. * * * * *Lovely world, where art thou? Turn, oh, turn thee,Fairest blossom-tide of Nature's spring!Only in the poet's realm of wonderLiv'st thou, still, – a fable vanishing.Reft of life the meadows lie deserted;Ne'er a godhead can my fancy see:Ah, if only of those living colorsLingered yet the ghost with me!171 * * * * *

It was the poem from which these stanzas are taken that provoked the well-known reply of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, contained in The Dead Pan. Her argument may be gathered from the following stanzas:

By your beauty which confessesSome chief Beauty conquering you,By our grand heroic guessesThrough your falsehood at the True,We will weep not! earth shall rollHeir to each god's aureole,And Pan is dead.Earth outgrows the mythic fanciesSung beside her in her youth;And those debonair romancesSound but dull beside the truth.Phœbus' chariot course is run!Look up, poets, to the sun!Pan, Pan is dead.130. Stedman's Pan in Wall Street. 172 That Pan, however, is not yet dead but alive even in the practical atmosphere of our western world, the poem here appended, written by one of our recently deceased American poets, would indicate.

Just where the Treasury's marble frontLooks over Wall Street's mingled nations;Where Jews and Gentiles most are wontTo throng for trade and last quotations;Where, hour by hour, the rates of goldOutrival, in the ears of people,The quarter chimes, serenely tolledFrom Trinity's undaunted steeple, —Even there I heard a strange, wild strainSound high above the modern clamor,Above the cries of greed and gain,The curbstone war, the auction's hammer;And swift, on Music's misty ways,It led, from all this strife for millions,To ancient, sweet-do-nothing daysAmong the kirtle-robed Sicilians.

Fig. 103. The Music Lesson

And as it still'd the multitude,And yet more joyous rose, and shriller,I saw the minstrel where he stoodAt ease against a Doric pillar:One hand a droning organ play'd,The other held a Pan's pipe (fashionedLike those of old) to lips that madeThe reeds give out that strain impassioned.'T was Pan himself had wandered here,A-strolling through the sordid city,And piping to the civic earThe prelude of some pastoral ditty!The demigod had cross'd the seas, —From haunts of shepherd, nymph, and satyr,And Syracusan times, – to theseFar shores and twenty centuries later.A ragged cap was on his head:But – hidden thus – there was no doubtingThat, all with crispy locks o'erspread,His gnarlèd horns were somewhere sprouting;His club-feet, cased in rusty shoes,Were cross'd, as on some frieze you see them.And trousers, patched of divers hues,Conceal'd his crooked shanks beneath them.

Fig. 104. Bacchic Dance

He filled the quivering reeds with sound,And o'er his mouth their changes shifted,And with his goat's-eyes looked aroundWhere'er the passing current drifted;And soon, as on Trinacrian hillsThe nymphs and herdsmen ran to hear him,Even now the tradesmen from their tills,With clerks and porters, crowded near him.The bulls and bears together drewFrom Jauncey Court and New Street Alley,As erst, if pastorals be true,Came beasts from every wooded valley;The random passers stay'd to list, —A boxer Ægon, rough and merry, —Broadway Daphnis, on his trystWith Naïs at the Brooklyn Ferry.

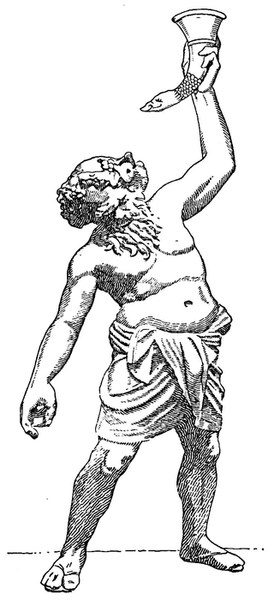

Fig. 105. Silenus

A one-eyed Cyclops halted longIn tatter'd cloak of army pattern,And Galatea joined the throng, —A blowsy, apple-vending slattern;While old Silenus stagger'd outFrom some new-fangled lunch-house handyAnd bade the piper, with a shout,To strike up "Yankee Doodle Dandy!"A newsboy and a peanut girlLike little Fauns began to caper:His hair was all in tangled curl,Her tawny legs were bare and taper.And still the gathering larger grew,And gave its pence and crowded nigher,While aye the shepherd-minstrel blewHis pipe, and struck the gamut higher.O heart of Nature! beating stillWith throbs her vernal passion taught her, —Even here, as on the vine-clad hill,Or by the Arethusan water!New forms may fold the speech, new landsArise within these ocean-portals,But Music waves eternal wands, —Enchantress of the souls of mortals!So thought I, – but among us trodA man in blue with legal baton;And scoff'd the vagrant demigod,And push'd him from the step I sat on.Doubting I mused upon the cry —"Great Pan is dead!" – and all the peopleWent on their ways: – and clear and highThe quarter sounded from the steeple.

Fig. 106. Satyr

131. Other Lesser Gods of Earth. Of the company of the lesser gods of earth, besides Pan, were the Sileni, the Sylvans, the Fauns, and the Satyrs, all male; the Oreads and the Dryads or Hamadryads, female. To these may be added the Naiads, for, although they dwelt in the streams, their association with the deities of earth was intimate. Of the nymphs, the Oreads and the Naiads were immortal. The love of Pan for Syrinx has already been mentioned, and his musical contest with Apollo. Of Silenus we have seen something in the adventures of Bacchus. What kind of existence the Satyr enjoyed is conveyed in the following soliloquy:

Fig. 107. Satyr swinging Maiden

The trunk of this tree,Dusky-leaved, shaggy-rooted,Is a pillow well suitedTo a hybrid like me,Goat-bearded, goat-footed;For the boughs of the gladeMeet above me, and throwA cool, pleasant shadeOn the greenness below;Dusky and brown'dClose the leaves all around;And yet, all the while,Thro' the boughs I can seeA star, with a smile,Looking at me…

Fig. 108. Satyr Drinking

Why, all day long,I run aboutWith a madcap throng,And laugh and shout.Silenus gripsMy ears, and stridesOn my shaggy hips,And up and downIn an ivy crownTipsily rides;And when in dozeHis eyelids close,Off he tumbles, and ICan his wine-skin steal,I drink – and feelThe grass roll – sea high;Then with shouts and yells,Down mossy dells,I stagger afterThe wood-nymphs fleet,Who with mocking laughterAnd smiles retreat;And just as I claspA yielding waist,With a cry embraced,– Gush! it melts from my graspInto water cool,And – bubble! trouble!Seeing double!I stumble and gaspIn some icy pool!173

132. Echo and Narcissus. 174 Echo was a beautiful Oread, fond of the woods and hills, a favorite of Diana, whom she attended in the chase. But by her chatter she came under the displeasure of Juno, who condemned her to the loss of voice save for purposes of reply.

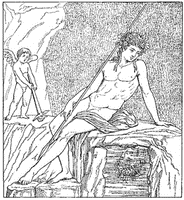

Fig. 109. Narcissus

Subsequently having fallen in love with Narcissus, the beautiful son of the river-god Cephissus, Echo found it impossible to express her regard for him in any way but by mimicking what he said; and what he said, unfortunately, did not always convey her sentiments. When, however, he once called across the hills to her, "Let us join one another," the maid, answering with all her heart, hastened to the spot, ready to throw her arms about his neck. He started back, exclaiming, "Hands off! I would rather die than thou shouldst have me!" "Have me," said she; but in vain. From that time forth she lived in caves and among mountain cliffs, and faded away till there was nothing left of her but her voice. But through his future fortunes she was constant to her cruel lover.

This Narcissus was the embodiment of self-conceit. He shunned the rest of the nymphs as he had shunned Echo. One maiden, however, uttered a prayer that he might some time or other feel what it was to love and meet no return of affection. The avenging goddess heard. Narcissus, stooping over a river brink, fell in love with his own image in the water. He talked to it, tried to embrace it, languished for it, and pined until he died. Indeed, even after death, it is said that when his shade passed the Stygian river it leaned over the boat to catch a look of itself in the waters. The nymphs mourned for Narcissus, especially the water-nymphs; and when they smote their breasts, Echo smote hers also. They prepared a funeral pile and would have burned the body, but it was nowhere to be found. In its place had sprung up a flower, purple within and surrounded with white leaves, which bears the name and preserves the memory of the son of Cephissus.

133. Echo, Pan, Lyde, and the Satyr. Another interesting episode in the life of Echo is given by Moschus:175

Pan loved his neighbor Echo; Echo lovedA gamesome Satyr; he, by her unmoved,Loved only Lyde; thus through Echo, Pan,Lyde, and Satyr, Love his circle ran.Thus all, while their true lovers' hearts they grieved,Were scorned in turn, and what they gave received.O all Love's scorners, learn this lesson true:Be kind to love, that he be kind to you.134. The Naiads. These nymphs guarded streams and fountains of fresh water and, like the Naiad who speaks in the following verses, kept them sacred for Diana or some other divinity.

Dian white-arm'd has given me this cool shrineDeep in the bosom of a wood of pine:The silver-sparkling showersThat hive me in, the flowersThat prink my fountain's brim, are hers and mine;And when the days are mild and fair,And grass is springing, buds are blowing,Sweet it is, 'mid waters flowing,Here to sit and know no care,'Mid the waters flowing, flowing, flowing,Combing my yellow, yellow hair.The ounce and panther down the mountain sideCreep thro' dark greenness in the eventide;And at the fountain's brinkCasting great shades, they drink,Gazing upon me, tame and sapphire-eyed;For, awed by my pale face, whose lightGleameth thro' sedge and lilies yellowThey, lapping at my fountain mellow,Harm not the lamb that in affrightThrows in the pool so mellow, mellow, mellow,Its shadow small and dusky-white.Oft do the fauns and satyrs, flusht with play,Come to my coolness in the hot noonday.Nay, once indeed, I vowBy Dian's truthful brow,The great god Pan himself did pass this way,And, all in festal oak-leaves clad,His limbs among these lilies throwing,Watch'd the silver waters flowing,Listen'd to their music glad,Saw and heard them flowing, flowing, flowing,And ah! his face was worn and sad!Mild joys like silvery waters fall;But it is sweetest, sweetest far of all,In the calm summer night,When the tree-tops look white,To be exhaled in dew at Dian's call,Among my sister-clouds to moveOver the darkness, earth bedimming,Milky-robed thro' heaven swimming,Floating round the stars above,Swimming proudly, swimming proudly, swimming,And waiting on the Moon I love.So tenderly I keep this cool, green shrine,Deep in the bosom of a wood of pine;Faithful thro' shade and sun,That service due and doneMay haply earn for me a place divineAmong the white-robed deitiesThat thread thro' starry paths, attendingMy sweet Lady, calmly wendingThro' the silence of the skies,Changing in hues of beauty never ending,Drinking the light of Dian's eyes.176135. The Dryads, or Hamadryads, assumed at times the forms of peasant girls, shepherdesses, or followers of the hunt. But they were believed to perish with certain trees which had been their abode and with which they had come into existence. Wantonly to destroy a tree was therefore an impious act, sometimes severely punished, as in the cases of Erysichthon and Dryope.

136. Erysichthon,177 a despiser of the gods, presumed to violate with the ax a grove sacred to Ceres. A venerable oak, whereon votive tablets had often been hung inscribed with the gratitude of mortals to the nymph of the tree, – an oak round which the Dryads hand in hand had often danced, – he ordered his servants to fell. When he saw them hesitate, he snatched an ax from one, and boasting that he cared not whether it were a tree beloved of the goddess or not, addressed himself to the task. The oak seemed to shudder and utter a groan. When the first blow fell upon the trunk, blood flowed from the wound. Warned by a bystander to desist, Erysichthon slew him; warned by a voice from the nymph of the tree, he redoubled his blows and brought down the oak. The Dryads invoked punishment upon Erysichthon.

The goddess Ceres, whom they had supplicated, nodded her assent. She dispatched an Oread to ice-clad Scythia, where Cold abides, and Fear and Shuddering and Famine. At Mount Caucasus, the Oread stayed the dragons of Ceres that drew her chariot; for afar off she beheld Famine, forespent with hunger, pulling up with teeth and claws the scanty herbage from a stony field. To her the nymph delivered the commands of Ceres, then returned in haste to Thessaly, for she herself began to be an hungered.

The orders of Ceres were executed by Famine, who, speeding through the air, entered the dwelling of Erysichthon and, as he slept, enfolded him with her wings and breathed herself into him. In his dreams the caitiff craved food; and when he awoke, his hunger raged. The more he ate, the more he craved, till, in default of money, he sold his daughter into slavery for edibles. Neptune, however, rescued the girl by changing her into a fisherman; and in that form she assured the slave-owner that she had seen no woman or other person, except herself, thereabouts. Then, resuming her own appearance, she was again and again sold by her father; while by Neptune's favor she became on each occasion a different animal, and so regained her home. Finally, increasing demands of hunger compelled the father to devour his own limbs; and in due time he finished himself off.

137. Dryope, the wife of Andræmon, purposing with her sister Iole to gather flowers for the altars of the nymphs, plucked the purple blossoms of a lotus plant that grew near the water, and offered them to her child. Iole, about to do the same thing, perceived that the stem of the plant was bleeding. Indeed, the plant was none other than a nymph, Lotis, who, escaping from a base pursuer, had been thus transformed.

Dryope would have hastened from the spot, but the displeasure of the nymph had fallen upon her. While protesting her innocence, she began to put forth branches and leaves. Praying her husband to see that no violence was done to her, to remind their child that every flower or bush might be a goddess in disguise, to bring him often to be nursed under her branches, and to teach him to say "My mother lies hid under this bark," – the luckless woman assumed the shape of a lotus.

138. Rhœcus. 178 The Hamadryads could appreciate services as well as punish injuries.

Hear now this fairy legend of old Greece,As full of freedom, youth, and beauty still,As the immortal freshness of that graceCarved for all ages on some Attic frieze.179Rhœcus, happening to see an oak just ready to fall, propped it up. The nymph, who had been on the point of perishing with the tree, expressed her gratitude to him and bade him ask what reward he would. Rhœcus boldly asked her love, and the nymph yielded to his desire. At the same time charging him to be mindful and constant, she promised to expect him an hour before sunset and, meanwhile, to communicate with him by means of her messenger, – a bee:

Now, in those days of simpleness and faith,Men did not think that happy things were dreamsBecause they overstepped the narrow bournOf likelihood, but reverently deemedNothing too wondrous or too beautifulTo be the guerdon of a daring heart.So Rhœcus made no doubt that he was blest,And all along unto the city's gateEarth seemed to spring beneath him as he walked,The clear, broad sky looked bluer than its wont,And he could scarce believe he had not wings,Such sunshine seemed to glitter through his veinsInstead of blood, so light he felt and strange.But the day was past its noon. Joining some comrades over the dice, Rhœcus forgot all else. A bee buzzed about his ear. Impatiently he brushed it aside:

Then through the window flew the wounded bee,And Rhœcus, tracking him with angry eyes,Saw a sharp mountain peak of ThessalyAgainst the red disk of the setting sun, —And instantly the blood sank from his heart…… Quite spent and out of breath he reached the tree,And, listening fearfully, he heard once moreThe low voice murmur, "Rhœcus!" close at hand:Whereat he looked around him, but could seeNaught but the deepening glooms beneath the oak.Then sighed the voice, "O Rhœcus! nevermoreShalt thou behold me or by day or night,Me, who would fain have blessed thee with a loveMore ripe and bounteous than ever yetFilled up with nectar any mortal heart:But thou didst scorn my humble messengerAnd sent'st him back to me with bruisèd wings.We spirits only show to gentle eyes,We ever ask an undivided love,And he who scorns the least of Nature's worksIs thenceforth exiled and shut out from all.Farewell! for thou canst never see me more."Then Rhœcus beat his breast, and groaned aloud,And cried, "Be pitiful! forgive me yetThis once, and I shall never need it more!""Alas!" the voice returned, "'tis thou art blind,Not I unmerciful; I can forgive,But have no skill to heal thy spirit's eyes;Only the soul hath power o'er itself."With that again there murmured, "Nevermore!"And Rhœcus after heard no other sound,Except the rattling of the oak's crisp leaves,Like the long surf upon a distant shore,Raking the sea-worn pebbles up and down.The night had gathered round him: o'er the plainThe city sparkled with its thousand lights,And sounds of revel fell upon his earHarshly and like a curse; above, the sky,With all its bright sublimity of stars,Deepened, and on his forehead smote the breeze:Beauty was all around him and delight,But from that eve he was alone on earth.According to the older tradition, the nymph deprived Rhœcus of his physical sight; but the superior insight of Lowell's interpretation is evident.

139. Pomona and Vertumnus. 180 Pomona was a Hamadryad of Roman mythology, guardian especially of the apple orchards, but presiding also over other fruits. "Bear me, Pomona," sings one of our poets, —

Bear me, Pomona, to thy citron groves,To where the lemon and the piercing lime,With the deep orange, glowing through the green,Their lighter glories blend. Lay me reclinedBeneath the spreading tamarind that shakes,Fanned by the breeze, its fever-cooling fruit.181

Fig. 110. A Rustic

This nymph had scorned the offers of love made her by Pan, Sylvanus, and innumerable Fauns and Satyrs. Vertumnus, too, she had time and again refused. But he, the deity of gardens and of the changing seasons, unwearied, wooed her in as many guises as his seasons themselves could assume. Now as a reaper, now as haymaker, now as plowman, now as vinedresser, now as apple-picker, now as fisherman, now as soldier, – all to no avail. Finally, as an old woman, he came to her, admired her fruit, admired especially the luxuriance of her grapes, descanted on the dependence of the luxuriant vine, close by, upon the elm to which it was clinging; advised Pomona, likewise, to choose some youth – say, for instance, the young Vertumnus – about whom to twine her arms. Then he told how the worthy Iphis, spurned by Anaxarete, had hanged himself to her gatepost; and how the gods had turned the hard-hearted virgin to stone even as she gazed on her lover's funeral. "Consider these things, dearest child," said the seeming old woman, "lay aside thy scorn and thy delays, and accept a lover. So may neither the vernal frosts blight thy young fruits, nor furious winds scatter thy blossoms!"

When Vertumnus had thus spoken, he dropped his disguise and stood before Pomona in his proper person, – a comely youth. Such wooing, of course, could not but win its just reward.