полная версия

полная версияThe Classic Myths in English Literature and in Art (2nd ed.) (1911)

When Pygmalion reached his home, to his amazement he saw before him his statue garlanded with flowers.

Yet while he stood, and knew not what to doWith yearning, a strange thrill of hope there came,A shaft of new desire now pierced him through,And therewithal a soft voice called his name,And when he turned, with eager eyes aflame,He saw betwixt him and the setting sunThe lively image of his lovèd one.He trembled at the sight, for though her eyes,Her very lips, were such as he had made,And though her tresses fell but in such guiseAs he had wrought them, now was she arrayedIn that fair garment that the priests had laidUpon the goddess on that very morn,Dyed like the setting sun upon the corn.Speechless he stood, but she now drew anear,Simple and sweet as she was wont to be,And once again her silver voice rang clear,Filling his soul with great felicity,And thus she spoke, "Wilt thou not come to me,O dear companion of my new-found life,For I am called thy lover and thy wife?.."My sweet," she said, "as yet I am not wise,Or stored with words aright the tale to tell,But listen: when I opened first mine eyesI stood within the niche thou knowest well,And from my hand a heavy thing there fellCarved like these flowers, nor could I see things clear,But with a strange, confusèd noise could hear."At last mine eyes could see a woman fair,But awful as this round white moon o'erhead,So that I trembled when I saw her there,For with my life was born some touch of dread,And therewithal I heard her voice that said,'Come down and learn to love and be alive,For thee, a well-prized gift, to-day I give.'"138A fuller account of Venus' address to the statue is the following:

O maiden, in mine image made!O grace that shouldst endure!While temples fall, and empires fade,Immaculately pure:Exchange this endless life of artFor beauty that must die,And blossom with a beating heartInto mortality!Change, golden tresses of her hair,To gold that turns to gray;Change, silent lips, forever fair,To lips that have their day!Oh, perfect arms, grow soft with life,Wax warm, ere cold ye wane;Wake, woman's heart, from peace to strife,To love, to joy, to pain!139The maiden was called Galatea. Venus blessed the nuptials, and from the union Paphos was born, by whose name the city, sacred to Venus, is known.

106. Pyramus and Thisbe. 140 Pyramus was the handsomest youth and Thisbe the fairest maiden in Babylonia, where Semiramis reigned. Their parents occupied adjoining houses. Propinquity brought the young people together, and acquaintance ripened into love. They would gladly have married, but their parents forbade. One thing, however, parents could not forbid (for Venus and Cupid favored the match), – that love should glow with equal ardor in the bosoms of both. They conversed by signs and glances, and the fire burned the more intensely that it was covered. In the wall between the two houses there was a crack, caused by some fault in the structure. It afforded a passage to the voice; and tender messages passed back and forth through the gap. When night came and they must say farewell, the lovers pressed their lips upon the wall, she on her side, he on his.

Fig. 80. Thisbe

From the painting by Edward Burne-Jones

One morning, when Aurora had put out the stars and the sun had melted the frost from the grass, they met at the accustomed spot and arranged a meeting for that night at a well-known edifice, standing without the city's bounds, – the Tomb of Ninus. The one who first arrived should await the other at the foot of a white mulberry tree near a cool spring. Evening came. Thisbe, arriving first, sat alone by the monument in the dim light of the evening. Suddenly she descried a lioness, her jaws reeking with recent slaughter, approaching the fountain to slake her thirst. The maiden fled at the sight, dropping her veil as she ran. The lioness, after drinking at the spring, turned toward the woods, and, seeing the veil on the ground, tossed and rent it with her bloody mouth.

Now Pyramus approached the place of meeting. He saw in the sand the footsteps of the lion. He found the veil all rent and bloody. "O, hapless girl," cried he, "I have been the cause of thy death; but I follow thee!" So saying, he drew his sword and plunged it into his heart. The blood spurted from the wound and tinged the white mulberries of the tree all red, and, sinking into the earth, reached the roots, so that the sanguine hue mounted through the trunk to the fruit.

By this time Thisbe, still trembling with fear, yet wishing not to disappoint her lover, stepped cautiously forth, looking anxiously for the youth, eager to tell him the danger she had escaped. When she came to the spot and saw the changed color of the mulberries, she doubted whether it was the same place. While she hesitated, she saw the form of her lover struggling in the agonies of death. She screamed and beat her breast, she embraced the lifeless body, poured tears into its wounds, and imprinted kisses on the cold lips. "O, Pyramus," she cried, "what has done this? It is thine own Thisbe that speaks." At the name of Thisbe Pyramus opened his eyes, then closed them again. She saw her veil stained with blood and the scabbard empty of its sword. "Thine own hand has slain thee, and for my sake," she said. "I, too, can be brave for once, and my love is as strong as thine. But ye, unhappy parents of us both, deny us not our united request. As love and death have joined us, let one tomb contain us. And thou, tree, retain the marks of slaughter. Let thy berries still serve for memorials of our blood." So saying, she plunged the sword into her breast. The two bodies were buried in one sepulcher, and the tree henceforth produced purple berries.

107. Phaon ferried a boat between Lesbos and Chios. One day the queen of Paphos and Amathus,141 in the guise of an ugly crone, begged a passage, which was so good-naturedly granted that in recompense she bestowed on the ferryman a salve possessing magical properties of youth and beauty. As a consequence of the use made of it by Phaon, the women of Lesbos went wild for love of him. None, however, admired him more than the poetess Sappho, who addressed to him some of her warmest and rarest love-songs.

108. The Vengeance of Venus. Venus did not fail to follow with her vengeance those who dishonored her rites or defied her power. The youth Hippolytus who, eschewing love, preferred Diana to her, she brought miserably to his ruin. Polyphonte she transformed into an owl, Arsinoë into a stone, and Myrrha into a myrtle tree.142 Her influence in the main was of mingled bane and blessing, as in the cases of Helen, Œnone, Pasiphaë, Ariadne, Procris, Eriphyle, Laodamia, and others whose stories are elsewhere told.143

109. Myths of Mercury. According to Homer,144 Maia bore Mercury at the peep of day, – a schemer subtle beyond all belief. He began playing on the lyre at noon; for, wandering out of the lofty cavern of Cyllene, he found a tortoise, picked it up, bored the life out of the beast, fitted the shell with bridge and reeds, and accompanied himself therewith as he sang a strain of unpremeditated sweetness. At evening of the same day he stole the oxen of his half brother Apollo from the Pierian mountains, where they were grazing. He covered their hoofs with tamarisk twigs, and, still further to deceive the pursuer, drove them backward into a cave at Pylos. There rubbing laurel branches together, he made fire and sacrificed, as an example for men to follow, two heifers to the twelve gods (himself included). Then home he went and slept, innocent as a new-born child! To his mother's warning that Apollo would catch and punish him, this innocent replied, in effect, "I know a trick better than that!" And when the puzzled Apollo, having traced the knavery to this babe in swaddling clothes, accused him of it, the sweet boy swore a great oath by his father's head that he stole not the cows, nor knew even what cows might be, for he had only that moment heard the name of them. Apollo proceeded to trounce the baby, with scant success, however, for Mercury persisted in his assumption of ignorance. So the twain appeared before their sire, and Apollo entered his complaint: he had not seen nor ever dreamed of so precocious a cattle-stealer, liar, and full-fledged knave as this young rascal. To all of which Mercury responded that he was, on the contrary, a veracious person, but that his brother Apollo was a coward to bully a helpless little new-born thing that slept, nor ever had thought of "lifting" cattle. The wink with which the lad of Cyllene accompanied this asseveration threw Jupiter into uncontrollable roars of laughter. Consequently, the quarrel was patched up: Mercury gave Apollo the new-made lyre; Apollo presented the prodigy with a glittering whiplash and installed him herdsman of his oxen. Nay even, when Mercury had sworn by sacred Styx no more to try his cunning in theft upon Apollo, that god in gratitude invested him with the magic wand of wealth, happiness, and dreams (the caduceus), it being understood, however, that Mercury should indicate the future only by signs, not by speech or song as did Apollo. It is said that the god of gain avenged himself for this enforced rectitude upon others: upon Venus, whose girdle he purloined; upon Neptune, whose trident he filched; upon Vulcan, whose tongs he borrowed; and upon Mars, whose sword he stole.

HERMES OF PRAXITELES

Fig. 81. Hermes and Dog

The most famous exploit of the Messenger, the slaughter of Argus, has already been narrated.

CHAPTER VIII

MYTHS OF THE GREAT DIVINITIES OF EARTH

110. Myths of Bacchus. Since the adventures of Ceres, although she was a goddess of earth, are intimately connected with the life of the underworld, they will be related in the sections pertaining to Proserpine and Pluto. The god of vernal sap and vegetation, of the gladness that comes of youth or of wine, the golden-curled, sleepy-eyed Bacchus (Dionysus), – his wanderings, and the fortunes of mortals brought under his influence (Pentheus, Acetes, Ariadne, and Midas), here challenge our attention.

Fig. 82. Silenus taking Dionysus to School

111. The Wanderings of Bacchus. After the death of Semele,145 Jove took the infant Bacchus and gave him in charge to the Nysæan nymphs, who nourished his infancy and childhood and for their care were placed by Jupiter, as the Hyades, among the stars. Another guardian and tutor of young Bacchus was the pot-bellied, jovial Silenus, son of Pan and a nymph, and oldest of the Satyrs. Silenus was probably an indulgent preceptor. He was generally tipsy and would have broken his neck early in his career, had not the Satyrs held him on his ass's back as he reeled along in the train of his pupil. After Bacchus was of age, he discovered the culture of the vine and the mode of extracting its precious juice; but Juno struck him with madness and drove him forth a wanderer through various parts of the earth. In Phrygia the goddess Rhea cured him and taught him her religious rites; and then he set out on a progress through Asia, teaching the people the cultivation of the vine. The most famous part of his wanderings is his expedition to India, which is said to have lasted several years. Returning in triumph, he undertook to introduce his worship into Greece, but was opposed by certain princes who dreaded the disorders and madness it brought with it. Finally, he approached his native city Thebes, where his own cousin, Pentheus, son of Agave and grandson of Harmonia and Cadmus, was king. Pentheus, however, had no respect for the new worship and forbade its rites to be performed.146 But when it was known that Bacchus was advancing, men and women, young and old, poured forth to meet him and to join his triumphal march.

Fig. 83. Bearded Dionysus and Satyr

Fauns with youthful Bacchus follow;Ivy crowns that brow, supernalAs the forehead of Apollo,And possessing youth eternal.Round about him fair Bacchantes,Bearing cymbals, flutes, and thyrses,Wild from Naxian groves or Zante'sVineyards, sing delirious verses.147

It was in vain Pentheus remonstrated, commanded, and threatened. His nearest friends and wisest counselors begged him not to oppose the god. Their remonstrances only made him the more violent.

112. The Story of Acetes. Soon the attendants returned who had been dispatched to seize Bacchus. They had succeeded in taking one of the Bacchanals prisoner, whom, with his hands tied behind him, they brought before the king. Pentheus, threatening him with death, commanded him to tell who he was and what these new rites were that he presumed to celebrate.

Fig. 84. Satyr and Mænad with Child Dionysus

The prisoner, unterrified, replied that he was Acetes of Mæonia; that his parents, being poor, had left him their fisherman's trade, which he had followed till he had acquired the pilot's art of steering his course by the stars. It once happened that he had touched at the island of Dia and had sent his men ashore for fresh water. They returned, bringing with them a lad of delicate appearance whom they had found asleep. Judging him to be a noble youth, they thought to detain him in the hope of liberal ransom. But Acetes suspected that some god was concealed under the youth's exterior, and asked pardon for the violence done. Whereupon the sailors, enraged by their lust of gain, exclaimed, "Spare thy prayers for us!" and, in spite of the resistance offered by Acetes, thrust the captive youth on board and set sail.

Then Bacchus (for the youth was indeed he), as if shaking off his drowsiness, asked what the trouble was and whither they were carrying him. One of the mariners replied, "Fear nothing; tell us where thou wouldst go, and we will convey thee thither." "Naxos is my home," said Bacchus; "take me there, and ye shall be well rewarded." They promised so to do; but, preventing the pilot from steering toward Naxos, they bore away for Egypt, where they might sell the lad into slavery. Soon the god looked out over the sea and said in a voice of weeping, "Sailors, these are not the shores ye promised me; yonder island is not my home. It is small glory ye shall gain by cheating a poor boy." Acetes wept to hear him, but the crew laughed at both of them and sped the vessel fast over the sea. All at once it stopped in mid-sea, as fast as if it were fixed on the ground. The men, astonished, pulled at their oars and spread more sail, but all in vain. Ivy twined round the oars and clung to the sails, with heavy clusters of berries. A vine laden with grapes ran up the mast and along the sides of the vessel. The sound of flutes was heard, and the odor of fragrant wine spread all around. The god himself had a chaplet of vine leaves and bore in his hand a spear wreathed with ivy. Tigers crouched at his feet, and forms of lynxes and spotted panthers played around him. The whole crew became dolphins and swam about the ship. Of twenty men Acetes alone was left. "Fear not," said the god; "steer towards Naxos." The pilot obeyed, and when they arrived there, kindled the altars and celebrated the sacred rites of Bacchus.

Fig. 85. Dionysus at Sea

So far had Acetes advanced in his narrative, when Pentheus, interrupting, ordered him off to his death. But from this fate the pilot, rendered invisible by his patron deity, was straightway rescued.

Meanwhile, the mountain Cithæron seemed alive with worshipers, and the cries of the Bacchanals resounded on every side. Pentheus, angered by the noise, penetrated through the wood and reached an open space where the chief scene of the orgies met his eyes. At the same moment the women saw him, among them his mother Agave, and Autonoë and Ino, her sisters. Taking him for a wild boar, they rushed upon him and tore him to pieces, – his mother shouting, "Victory! Victory! the glory is ours!"

So the worship of Bacchus was established in Greece.

It was on the island of Naxos that Bacchus afterward found Ariadne, the daughter of Minos, king of Crete, who had been deserted by her lover, Theseus. How Bacchus comforted her is related in another section. How the god himself is worshiped is told by Edmund Gosse in the poem from which the following extracts are taken:

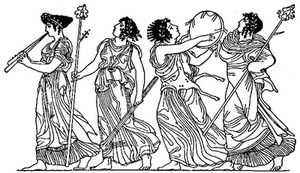

Fig. 86. Bacchic Procession

Behold, behold! the granite gates unclose,And down the vales a lyric people flows;Dancing to music, in their dance they flingTheir frantic robes to every wind that blows,And deathless praises to the vine-god sing.Nearer they press, and nearer still in sight,Still dancing blithely in a seemly choir;Tossing on high the symbol of their rite,The cone-tipped thyrsus of a god's desire;Nearer they come, tall damsels flushed and fair,With ivy circling their abundant hair;Onward, with even pace, in stately rows,With eye that flashes, and with cheek that glows,And all the while their tribute-songs they bring,And newer glories of the past disclose,And deathless praises to the vine-god sing.… But oh! within the heart of this great flight,Whose ivory arms hold up the golden lyre?What form is this of more than mortal height?What matchless beauty, what inspirèd ire!The brindled panthers know the prize they bear,And harmonize their steps with stately care;Bent to the morning, like a living rose,The immortal splendor of his face he shows,And where he glances, leaf and flower and wingTremble with rapture, stirred in their repose,And deathless praises to the vine-god sing…148

Fig. 87. Dionysus visiting a Poet

113. The Choice of King Midas. 149 Once Silenus, having wandered from the company of Bacchus in an intoxicated condition, was found by some peasants, who carried him to their king, Midas. Midas entertained him royally and on the eleventh day restored him in safety to his divine pupil. Whereupon Bacchus offered Midas his choice of a reward. The king asked that whatever he might touch should be changed into gold. Bacchus consented. Midas hastened to put his new-acquired power to the test. A twig of an oak, which he plucked from the branch, became gold in his hand. He took up a stone; it changed to gold. He touched a sod with the same result. He took an apple from the tree; you would have thought he had robbed the garden of the Hesperides. He ordered his servants, then, to set an excellent meal on the table. But, to his dismay, when he touched bread, it hardened in his hand; when he put a morsel to his lips, it defied his teeth. He took a glass of wine, but it flowed down his throat like melted gold.

He strove to divest himself of his power; he hated the gift he had lately coveted. He raised his arms, all shining with gold, in prayer to Bacchus, begging to be delivered from this glittering destruction. The merciful deity heard and sent him to wash away his fault and its punishment in the fountainhead of the river Pactolus. Scarce had Midas touched the waters, before the gold-creating power passed into them, and the river sands became golden, as they remain to this day.

Thenceforth Midas, hating wealth and splendor, dwelt in the country and became a worshiper of Pan, the god of the fields. But that he had not gained common sense is shown by the decision that he delivered somewhat later in favor of Pan's superiority, as a musician, over Apollo.150

CHAPTER IX

FROM THE EARTH TO THE UNDERWORLD

114. Myths of Ceres, Pluto, and Proserpine. The search of Ceres for Proserpine, and of Orpheus for Eurydice, are stories pertaining both to Earth and Hades.

115. The Rape of Proserpine. 151 When the giants were imprisoned by Jupiter under Mount Ætna, Pluto (Hades) feared lest the shock of their fall might expose his kingdom to the light of day. Under this apprehension, he mounted his chariot drawn by black horses, and made a circuit of inspection to satisfy himself of the extent of the damage. While he was thus engaged, Venus, who was sitting on Mount Eryx playing with her boy Cupid, espied him and said, "My son, take thy darts which subdue all, even Jove himself, and send one into the breast of yonder dark monarch, who rules the realm of Tartarus. Dost thou not see that even in heaven some despise our power? Minerva and Diana defy us; and there is that daughter of Ceres, goddess of earth, who threatens to follow their example. Now, if thou regardest thine own interest or mine, join these two in one." The boy selected his sharpest and truest arrow, and sped it right to the heart of Pluto.

In the vale of Enna is a lake embowered in woods, where Spring reigns perpetual. Here Proserpine (Persephone) was playing with her companions, gathering lilies and violets, and singing, one may imagine, such words as our poet Shelley puts into her mouth:

Sacred Goddess, Mother Earth,Thou from whose immortal bosom,Gods, and men, and beasts, have birth,Leaf and blade, and bud and blossom,Breathe thine influence most divineOn thine own child, Proserpine.If with mists of evening dewThou dost nourish these young flowersTill they grow, in scent and hue,Fairest children of the hours,Breathe thine influence most divineOn thine own child, Proserpine.152Pluto saw her, loved her, and carried her off. She screamed for help to her mother and her companions; but the ravisher urged on his steeds and outdistanced pursuit. When he reached the river Cyane, it opposed his passage, whereupon he struck the bank with his trident, and the earth opened and gave him a passage to Tartarus.

116. The Wanderings of Ceres. 153 Ceres (Demeter) sought her daughter all the world over. Bright-haired Aurora, when she came forth in the morning, and Hesperus, when he led out the stars in the evening, found her still busy in the search. At length, weary and sad, she sat down upon a stone, and remained nine days and nights in the open air, under the sunlight and moonlight and falling showers. It was where now stands the city of Eleusis, near the home of an old man named Celeus. His little girl, pitying the old woman, said to her, "Mother," – and the name was sweet to the ears of Ceres, – "why sittest thou here alone upon the rocks?" The old man begged her to come into his cottage. She declined. He urged her. "Go in peace," she replied, "and be happy in thy daughter; I have lost mine." But their compassion finally prevailed. Ceres rose from the stone and went with them. As they walked, Celeus said that his only son lay sick of a fever. The goddess stooped and gathered some poppies. Then, entering the cottage, where all was in distress, – for the boy Triptolemus seemed past recovery, – she restored the child to life and health with a kiss. In grateful happiness the family spread the table and put upon it curds and cream, apples, and honey in the comb. While they ate, Ceres mingled poppy juice in the milk of the boy. When night came, she arose and, taking the sleeping boy, molded his limbs with her hands, and uttered over him three times a solemn charm, then went and laid him in the ashes. His mother, who had been watching what her guest was doing, sprang forward with a cry and snatched the child from the fire. Then Ceres assumed her own form, and a divine splendor shone all around. While they were overcome with astonishment, she said, "Mother, thou hast been cruel in thy fondness; for I would have made thy son immortal. Nevertheless, he shall be great and useful. He shall teach men the use of the plow and the rewards which labor can win from the soil." So saying, she wrapped a cloud about her and mounting her chariot rode away.