полная версия

полная версияThe Classic Myths in English Literature and in Art (2nd ed.) (1911)

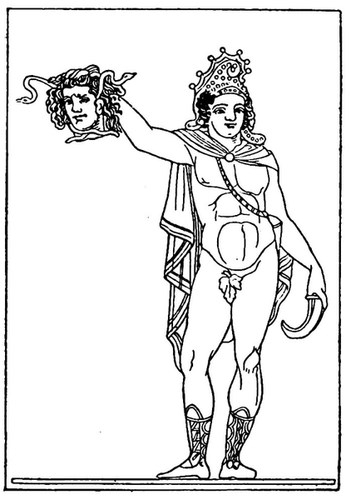

153. Perseus and Atlas. From the body of Medusa sprang the winged horse Pegasus, of whose rider, Bellerophon, we shall presently be informed.

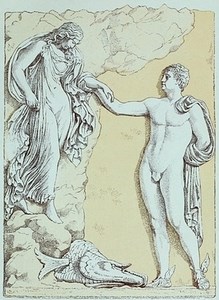

Fig. 120. Perseus with Head of Medusa

After the slaughter of Medusa, Perseus, bearing with him the head of the Gorgon, flew far and wide, over land and sea. As night came on, he reached the western limit of the earth, and would gladly have rested till morning. Here was the realm of Atlas, whose bulk surpassed that of all other men. He was rich in flocks and herds, but his chief pride was his garden of the Hesperides, whose fruit was of gold, hanging from golden branches, half hid with golden leaves. Perseus said to him, "I come as a guest. If thou holdest in honor illustrious descent, I claim Jupiter for my father; if mighty deeds, I plead the conquest of the Gorgon. I seek rest and food." But Atlas, remembering an ancient prophecy that had warned him against a son of Jove who should one day rob him of his golden apples, attempted to thrust the youth out. Whereupon Perseus, finding the giant too strong for him, held up the Gorgon's head. Atlas, with all his bulk, was changed into stone. His beard and hair became forests, his arms and shoulders cliffs, his head a summit, and his bones rocks. Each part increased in mass till the giant became the mountain upon whose shoulders rests heaven with all its stars.

154. Perseus and Andromeda. On his way back to Seriphus, the Gorgon-slayer arrived at the country of the Æthiopians, over whom Cepheus was king. His wife was Cassiopea —

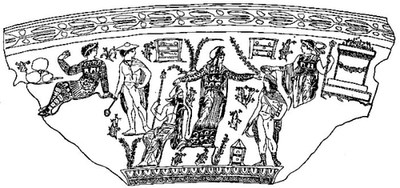

That starred Æthiope queen that stroveTo set her beauty's praise aboveThe sea-nymphs, and their powers offended.208These nymphs had consequently sent a sea monster to ravage the coast. To appease the deities, Cepheus was directed by the oracle to devote his daughter Andromeda to the ravening maw of the prodigy. As Perseus looked down from his aërial height, he beheld the virgin chained to a rock. Drawing nearer he pitied, then comforted her, and sought the reason of her disgrace. At first from modesty she was silent; but when he repeated his questions, for fear she might be thought guilty of some offense which she dared not tell, she disclosed her name and that of her country, and her mother's pride of beauty. Before she had done speaking, a sound was heard upon the water, and the monster appeared. The virgin shrieked; the father and mother, who had now arrived, poured forth lamentations and threw their arms about the victim. But the hero himself undertook to slay the monster, on condition that, if the maiden were rescued by his valor, she should be his reward. The parents consented. Perseus embraced his promised bride; then —

Loosing his arms from her waist he flew upward, awaiting the sea beast.Onward it came from the southward, as bulky and black as a galley,Lazily coasting along, as the fish fled leaping before it;Lazily breasting the ripple, and watching by sand bar and headland,Listening for laughter of maidens at bleaching, or song of the fisher,Children at play on the pebbles, or cattle that passed on the sand hills.Rolling and dripping it came, where bedded in glistening purpleCold on the cold seaweeds lay the long white sides of the maiden,Trembling, her face in her hands, and her tresses afloat on the water.209

Fig. 121. Perseus finds Andromeda

PERSEUS FREEING ANDROMEDA

The youth darted down upon the back of the monster and plunged his sword into its shoulder, then eluded its furious attack by means of his wings. Wherever he could find a passage for his sword, he plunged it between the scales of flank and side. The wings of the hero were finally drenched and unmanageable with the blood and water that the brute spouted. Then alighting on a rock and holding by a projection, he gave the monster his deathblow.

The joyful parents, with Perseus and Andromeda, repaired to the palace, where a banquet was opened for them. But in the midst of the festivities a noise was heard of warlike clamor, and Phineus, who had formerly been betrothed to the bride, burst in, demanding her for his own. In vain, Cepheus remonstrated that all such engagements had been dissolved by the sentence of death passed upon Andromeda, and that if Phineus had actually loved the girl, he would have tried to rescue her. Phineus and his adherents, persisting in their intent, attacked the wedding party and would have broken it up with most admired disorder, but

Mid the fabled Libyan bridal stoodPerseus in stern tranquillity of wrath,Half stood, half floated on his ankle plumesOut-swelling, while the bright face on his shieldLooked into stone the raging fray.210Leaving Phineus and his fellows in merited petrifaction, and conveying Andromeda to Seriphus, the hero there turned into stone Polydectes and his court, because the tyrant had rendered Danaë's life intolerable with his attentions. Perseus then restored to their owners the charmed helmet, the winged shoes, and the pouch in which he had conveyed the Gorgon's head. The head itself he bestowed upon Minerva, who bore it afterward upon her ægis or shield. Of that Gorgon shield no simpler moral interpretation can be framed than the following:

What was that snaky-headed Gorgon shieldThat wise Minerva wore, unconquered virgin,Wherewith she freezed her foes to congealed stone,But rigid looks of chaste austerity,And noble grace that dashed brute violenceWith sudden adoration and blank awe!211With his mother and his wife Perseus returned to Argos to seek his grandfather. But Acrisius, still fearing his doom, had retired to Larissa in Thessaly. Thither Perseus followed him, and found him presiding over certain funeral games. As luck would have it, the hero took part in the quoit throwing, and hurled a quoit far beyond the mark. The disk, falling upon his grandfather's foot, brought about the old man's death, and in that way the prophecy was fulfilled. Of Perseus and Andromeda three sons were born, through one of whom, Electryon, they became grandparents of the famous Alcmene, sweetheart of Jove and mother of Hercules.

155. Bellerophon and the Chimæra. 212 The horse Pegasus, which sprang from the Gorgon's blood, found a master in Bellerophon of Corinth. This youth was of the Hellenic branch of the Greek nation, being descended from Sisyphus and through him from Æolus, the son of Hellen.213 His adventures should therefore be recited with those of Jason and other descendants of Æolus in the next chapter, but that they follow so closely on those of Perseus. His father, Glaucus, king of Corinth, is frequently identified with Glaucus the fisherman. This Glaucus of Corinth was noted for his love of horse racing, his fashion of feeding his mares on human flesh, and his destruction by the fury of his horses; for having upset his chariot, they tore their master to pieces. As to his son, Bellerophon, the following is related:

In Lycia a monster, breathing fire, made great havoc. The fore part of his body was a compound of the lion and the goat; the hind part was a dragon's. The king, Iobates, sought a hero to destroy this Chimæra, as it was called. At that time Bellerophon arrived at his court. The gallant youth brought letters from Prœtus, the son-in-law of Iobates, recommending Bellerophon in the warmest terms as an unconquerable hero, but adding a request to his father-in-law to put him to death. For Prœtus, suspecting that his wife Antea looked with too great favor on the young warrior, schemed thus to destroy him.

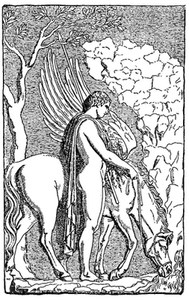

Iobates accordingly determined to send Bellerophon against the Chimæra. Bellerophon accepted the proposal, but before proceeding to the combat, consulted the soothsayer Polyidus, who counseled him to procure, if possible, the horse Pegasus for the conflict. Now this horse had been caught and tamed by Minerva and by her presented to the Muses. Polyidus, therefore, directed Bellerophon to pass the night in the temple of Minerva. While he slept, Minerva brought him a golden bridle. When he awoke, she showed him Pegasus drinking at the well of Pirene. At sight of the bridle, the winged steed came willingly and suffered himself to be taken. Bellerophon mounted him, sped through the air, found the Chimæra, and gained an easy victory.

Fig. 122. Bellerophon and Pegasus

After the conquest of this monster, Bellerophon was subjected to further trials and labors by his unfriendly host, but by the aid of Pegasus he triumphed over all. At length Iobates, seeing that the hero was beloved of the gods, gave him his daughter in marriage and made him his successor on the throne. It is said that Bellerophon, by his pride and presumption, drew upon himself the anger of the Olympians; that he even attempted to fly to heaven on his winged steed; but the king of gods and men sent a gadfly, which, stinging Pegasus, caused him to throw his rider, who wandered ever after lame, blind, and lonely through the Aleian field, and perished miserably.

156. Hercules (Heracles): His Youth. 214 Alcmene, daughter of Electryon and granddaughter of Perseus and Andromeda, was beloved of Jupiter. Their son, the mighty Hercules, born in Thebes, became the national hero of Greece. Juno, always hostile to the offspring of her husband by mortal mothers, declared war against Hercules from his birth. She sent two serpents to destroy him as he lay in his cradle, but the precocious infant strangled them with his hands. In his youth he passed for the son of his stepfather Amphitryon, king of Thebes, grandson of Perseus and Andromeda, and son of Alcæus. Hence his patronymic, Alcides. Rhadamanthus trained him in wisdom and virtue, Linus in music. Unfortunately the latter attempted one day to chastise Hercules; whereupon the pupil killed the master with a lute. After this melancholy breach of discipline, the youth was rusticated, – sent off to the mountains, where among the herdsmen and the cattle he grew to mighty stature, slew the Thespian lion, and performed various deeds of valor. To him, while still a youth, appeared, according to one story, two women at a meeting of the ways, – Pleasure and Duty. The gifts offered by Duty were the "Choice of Hercules." Soon afterward he contended with none other than Apollo for the tripod of Delphi; but reconciliation was effected between the combatants by the gods of Olympus, and from that day forth Apollo and Hercules remained true friends, each respecting the prowess of the other. Returning to Thebes, the hero aided his half brother Iphicles and his reputed father Amphitryon in throwing off the yoke of the city of Orchomenus, and was rewarded with the hand of the princess Megara. A few years later, while in the very pride of his manhood, he was driven insane by the implacable Juno. In his madness he slew his children, and would have slain Amphitryon, also, had not Minerva knocked him over with a stone and plunged him into a deep sleep, from which he awoke in his right mind. Next, for expiation of the bloodshed, he was rendered subject to his cousin Eurystheus and compelled to perform his commands. This humiliation, Juno, of course, had decreed.

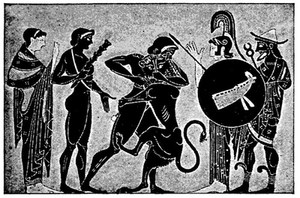

157. His Labors. Eurystheus enjoined upon the hero a succession of desperate undertakings, which are called the twelve "Labors of Hercules." The first was the combat with the lion that infested the valley of Nemea, the skin of which Hercules was ordered to bring to Mycenæ. After using in vain his club and arrows against the lion, Hercules strangled the animal with his hands and returned, carrying its carcass on his shoulders; but Eurystheus, frightened at the sight and at this proof of the prodigious strength of the hero, ordered him to deliver the account of his exploits, in future, outside the town.

Fig. 123. Heracles and the Nemean Lion

His second labor was the slaughter of the Hydra, a water serpent that ravaged the country of Argos and dwelt in a swamp near the well of Amymone. It had nine heads, of which the middle one was immortal. Hercules struck off the heads with his club; but in the place of each dispatched, two new ones appeared. At last, with the assistance of his faithful nephew Iolaüs, he burned away the other heads of the Hydra and buried the ninth, which was immortal, under a rock.

Fig. 124. Heracles and the Hydra

His third labor was the capture of a boar that haunted Mount Erymanthus in Arcadia. The adventure was, in itself, successful. But on the same journey Hercules made the friendship of the centaur Pholus, who, receiving him hospitably, poured out for him without stint the choicest wine that the centaurs possessed. As a consequence, Hercules became involved in a broil with the other centaurs of the mountain. Unfortunately his friend Pholus, drawing one of the arrows of Hercules from a brother centaur, wounded himself therewith and died of the poison.

The fourth labor of Hercules was the capture of a wonderful stag of golden antlers and brazen hoofs, that ranged the hills of Cerynea, between Arcadia and Achaia.

His fifth labor was the destruction of the Stymphalian birds, which with cruel beaks and sharp talons harassed the inhabitants of the valley of Stymphalus, devouring many of them.

His sixth labor was the cleaning of the Augean stables. Augeas, king of Elis, had a herd of three thousand oxen, whose stalls had not been cleansed for thirty years. Hercules, bringing the rivers Alpheüs and Peneüs through them, purified them thoroughly in one day.

Fig. 125. Heracles bringing Home the Boar

His seventh labor was the overthrow of the Cretan bull, – an awful but beautiful brute, at once a gift and a curse bestowed by Neptune upon Minos of Crete.215 This monster Hercules brought to Mycenæ.

His eighth labor was the removal of the horses of Diomedes, king of Thrace. These horses subsisted on human flesh, were swift and fearful. Diomedes, attempting to retain them, was killed by Hercules and given to the horses to devour. They were then delivered to Eurystheus; but, escaping, they roamed the hills of Arcadia, till the wild beasts of Apollo tore them to pieces.

His ninth labor was of a more delicate character. Admeta, the daughter of Eurystheus, desired the girdle of the queen of the Amazons, and Eurystheus ordered Hercules to get it. The Amazons were a nation dominated by warlike women, and in their hands were many cities. It was their custom to bring up only the female children, whom they hardened by martial discipline; the boys were either dispatched to the neighboring nations or put to death. Hippolyta, the queen, received Hercules kindly and consented to yield him the girdle; but Juno, taking the form of an Amazon, persuaded the people that the strangers were carrying off their queen. They instantly armed and beset the ship. Whereupon Hercules, thinking that Hippolyta had acted treacherously, slew her and, taking her girdle, made sail homeward.

Fig. 126. Heracles with the Bull

The tenth task enjoined upon him was to capture for Eurystheus the oxen of Geryon, a monster with three bodies, who dwelt in the island Erythea (the red), – so called because it lay in the west, under the rays of the setting sun. This description is thought to apply to Spain, of which Geryon was king. After traversing various countries, Hercules reached at length the frontiers of Libya and Europe, where he raised the two mountains of Abyla and Calpe as monuments of his progress, – the Pillars of Hercules; or, according to another account, rent one mountain into two and left half on each side, forming the Strait of Gibraltar. The oxen were guarded by the giant Eurytion and his two-headed dog, but Hercules killed the warders and conveyed the oxen in safety to Eurystheus.

One of the most difficult labors was the eleventh, – the robbery of the golden apples of the Hesperides. Hercules did not know where to find them; but after various adventures, arrived at Mount Atlas in Africa. Since Atlas was the father of the Hesperides, Hercules thought he might through him obtain the apples. The hero, accordingly, taking the burden of the heavens on his own shoulders,216 sent Atlas to seek the apples. The giant returned with them and proposed to take them himself to Eurystheus. "Even so," said Hercules; "but, pray, hold this load for me a moment, while I procure a pad to ease my shoulders." Unsuspectingly the giant resumed the burden of the heavens. Hercules took the apples.

Fig. 127 Heracles and Cerberus

His twelfth exploit was to fetch Cerberus from the lower world. To this end he descended into Hades, accompanied by Mercury and Minerva. There he obtained permission from Pluto to carry Cerberus to the upper air, provided he could do it without the use of weapons. In spite of the monster's struggling he seized him, held him fast, carried him to Eurystheus, and afterward restored him to the lower regions. While in Hades, Hercules also obtained the liberty of Theseus, his admirer and imitator, who had been detained there for an attempt at abducting Proserpine.217

After his return from Hades to his native Thebes, he renounced his wife Megara, for, having slain his children by her in his fit of madness, he looked upon the marriage as displeasing to the gods.

Two other exploits not recorded among the twelve labors are the victories over Antæus and Cacus. Antæus, the son of Poseidon and Gæa, was a giant and wrestler whose strength was invincible so long as he remained in contact with his mother Earth. He compelled all strangers who came to his country to wrestle with him, on condition that if conquered, they should suffer death.

Hercules encountered him and, finding that it was of no avail to throw him, – for he always rose with renewed strength from every fall, – lifted him up from the earth and strangled him in the air.

Later writers tell of an army of Pygmies which, finding Hercules asleep after his defeat of Antæus, made preparations to attack him, as if they were about to attack a city. But the hero, awakening, laughed at the little warriors, wrapped some of them up in his lion's skin, and carried them to Eurystheus.

Fig. 128. Heracles and Antæus

Cacus was a giant who inhabited a cave on Mount Aventine and plundered the surrounding country. When Hercules was driving home the oxen of Geryon, Cacus stole part of the cattle while the hero slept. That their footprints might not indicate where they had been driven, he dragged them backward by their tails to his cave. Hercules was deceived by the stratagem and would have failed to find his oxen, had it not happened that while he was driving the remainder of the herd past the cave where the stolen ones were concealed, those within, beginning to low, discovered themselves to him. Hercules promptly dispatched the thief.

Through most of these expeditions Hercules was attended by Iolaüs, his devoted friend, the son of his half brother Iphicles.

158. His Later Exploits. On the later exploits of the hero we can dwell but briefly. Having, in a fit of madness, killed his friend Iphitus, he was condemned for the offense to spend three years as the slave of Queen Omphale. He lived effeminately, wearing at times the dress of a woman and spinning wool with the handmaidens of Omphale, while the queen wore his lion's skin. But during this period he contrived to engage in about as many adventures as would fill the life of an ordinary hero. He rescued Daphnis from Lityerses and threw the bloodthirsty king218 into the river Mæander; he discovered the body of Icarus219 and buried it; he joined the company of Argonauts, who were on their way to Colchis to secure the golden fleece, and he captured the thievish gnomes, called Cercopes. Two of these grotesque rascals had made off with the weapons of Hercules while he was sleeping. When he had caught them he strapped them, knees upward, to a yoke and so bore them away. Their drollery, however, regained them their liberty. It is said that some of them having once deceived Jupiter were changed to apes.

159. The Loss of Hylas. 220 In the Argonautic adventure Hercules was attended by a lad, Hylas, whom he tenderly loved and on whose account he deserted the expedition in Mysia; for Hylas had been stolen by the Naiads.

… Never was Heracles apart from Hylas, not when midnoon was high in heaven, not when Dawn with her white horses speeds upwards to the dwelling of Zeus, not when the twittering nestlings look towards the perch, while their mother flaps her wings above the smoke-browned beam; and all this that the lad might be fashioned to his mind, and might drive a straight furrow, and come to the true measure of man…

And Hylas of the yellow hair, with a vessel of bronze in his hand, went to draw water against supper-time for Heracles himself and the steadfast Telamon, for these comrades twain supped ever at one table. Soon was he ware of a spring in a hollow land, and the rushes grew thickly round it, and dark swallowwort, and green maidenhair, and blooming parsley, and deer grass spreading through the marshy land. In the midst of the water the nymphs were arranging their dances, – the sleepless nymphs, dread goddesses of the country people, Eunice, and Malis, and Nycheia, with her April eyes. And now the boy was holding out the wide-mouthed pitcher to the water, intent on dipping it; but the nymphs all clung to his hand, for love of the Argive lad had fluttered the soft hearts of all of them. Then down he sank into the black water, headlong all, as when a star shoots flaming from the sky, plumb in the deep it falls; and a mate shouts out to the seamen, "Up with the gear, my lads, the wind is fair for sailing."

Then the nymphs held the weeping boy on their laps, and with gentle words were striving to comfort him. But the son of Amphitryon was troubled about the lad, and went forth, carrying his bended bow in Scythian fashion, and the club that is ever grasped in his right hand. Thrice he shouted, "Hylas!" as loud as his deep throat could call, and thrice again the boy heard him, and thrice came his voice from the water, and, hard by though he was, he seemed very far away. And as when a bearded lion, a ravening lion on the hills, hears the bleating of a fawn afar off and rushes forth from his lair to seize it, his readiest meal, even so the mighty Heracles, in longing for the lad, sped through the trackless briars and ranged over much country.

Reckless are lovers: great toils did Heracles bear, in hills and thickets wandering; and Jason's quest was all postponed to this…

Thus loveliest Hylas is numbered with the Blessed; but for a runaway they girded at Heracles – the heroes – because he roamed from Argo of the sixty oarsmen. But on foot he came to Colchis and inhospitable Phasis.