полная версия

полная версияThe Classic Myths in English Literature and in Art (2nd ed.) (1911)

Fig. 89. Hades and Persephone

Ceres continued her search for her daughter till at length she returned to Sicily, whence she first had set out, and stood by the banks of the river Cyane. The river nymph would have told the goddess all she had witnessed, but dared not, for fear of Pluto; so she ventured merely to take up the girdle which Proserpine had dropped in her flight, and float it to the feet of the mother. Ceres, seeing this, laid her curse on the innocent earth in which her daughter had disappeared. Then succeeded drought and famine, flood and plague, until, at last, the fountain Arethusa made intercession for the land. For she had seen that it opened only unwillingly to the might of Pluto; and she had also, in her flight from Alpheüs through the lower regions of the earth, beheld the missing Proserpine. She said that the daughter of Ceres seemed sad, but no longer showed alarm in her countenance. Her look was such as became a queen, – the queen of Erebus; the powerful bride of the monarch of the realms of the dead.

Fig. 90. Sacrifice to Demeter and Persephone

When Ceres heard this, she stood awhile like one stupefied; then she implored Jupiter to interfere to procure the restitution of her daughter. Jupiter consented on condition that Proserpine should not during her stay in the lower world have taken any food; otherwise, the Fates forbade her release. Accordingly, Mercury was sent, accompanied by Spring, to demand Proserpine of Pluto. The wily monarch consented; but alas! the maiden had taken a pomegranate which Pluto offered her, and had sucked the sweet pulp from a few of the seeds. A compromise, however, was effected by which she was to pass half the time with her mother, and the rest with the lord of Hades.

Of modern poems upon the story of the maiden seized in the vale of Enna, none conveys a lesson more serene of the beauty of that dark lover of all fair life, Death, than the Proserpine of Woodberry, from which we quote the three following stanzas. "I pick," says the poet wandering through the vale of Enna,

I pick the flowers that Proserpine let fall,Sung through the world by every honeyed muse:Wild morning-glories, daisies waving tall,At every step is something new to choose;And oft I stop and gazeUpon the flowery maze;By yonder cypresses on that soft rise,Scarce seen through poppies and the knee-deep wheat,Juts the dark cleft where on her came the fleetThunder-black horses and the cloud's surpriseAnd he who filled the place.Did marigolds bright as these, gilding the mist,Drop from her maiden zone? Wert thou last kissed,Pale hyacinth, last seen, before his face? * * * * *Oh, whence has silence stolen on all things here,Where every sight makes music to the eye?Through all one unison is singing clear;All sounds, all colors in one rapture die.Breathe slow, O heart, breathe slow!A presence from belowMoves toward the breathing world from that dark deep,Whereof men fabling tell what no man knows,By little fires amid the winter snows,When earth lies stark in her titanic sleepAnd doth with cold expire;He brings thee all, O Maiden flower of earth,Her child in whom all nature comes to birth,Thee, the fruition of all dark desire. * * * * *O Proserpine, dream not that thou art goneFar from our loves, half-human, half-divine;Thou hast a holier adoration wonIn many a heart that worships at no shrine.Where light and warmth behold me,And flower and wheat infold me,I lift a dearer prayer than all prayers past:He who so loved thee that the live earth cloveBefore his pathway unto light and love,And took thy flower-full bosom, – who at lastShall every blossom cull, —Lover the most of what is most our own,The mightiest lover that the world has known,Dark lover, Death, – was he not beautiful?154

Fig. 91. Triptolemus and the Eleusinian Deities

117. Triptolemus and the Eleusinian Mysteries. Ceres, pacified with this arrangement, restored the earth to her favor. Now she remembered, also, Celeus and his family, and her promise to his infant son Triptolemus. She taught the boy the use of the plow and how to sow the seed. She took him in her chariot, drawn by winged dragons, through all the countries of the earth; and under her guidance he imparted to mankind valuable grains and the knowledge of agriculture. After his return Triptolemus built a temple to Ceres in Eleusis and established the worship of the goddess under the name of the Eleusinian mysteries, which in the splendor and solemnity of their observance surpassed all other religious celebrations among the Greeks.

Fig. 92. Demeter, Triptolemus, and Proserpina

118. Orpheus and Eurydice.155 Of mortals who have visited Hades and returned, none has a sweeter or sadder history than Orpheus, son of Apollo and the Muse Calliope. Presented by his father with a lyre and taught to play upon it, he became the most famous of musicians, and not only his fellow mortals but even the wild beasts were softened by his strains. The very trees and rocks were sensible to the charm. And so also was Eurydice, – whom he loved and won.

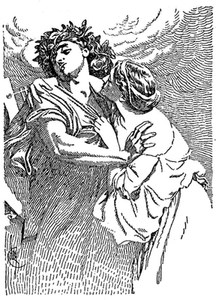

Fig. 93. Orpheus and Eurydice

From the painting by Lord Leighton

Hymen was called to bless with his presence the nuptials of Orpheus with Eurydice, but he conveyed no happy omens with him. His torch smoked and brought tears into the eyes. In keeping with such sad prognostics, Eurydice, shortly after her marriage, was seen by the shepherd Aristæus, who was struck with her beauty and made advances to her. As she fled she trod upon a snake in the grass, and was bitten in the foot. She died. Orpheus sang his grief to all who breathed the upper air, both gods and men, and finding his complaint of no avail, resolved to seek his wife in the regions of the dead. He descended by a cave situated on the side of the promontory of Tænarus, and arrived in the Stygian realm. He passed through crowds of ghosts and presented himself before the throne of Pluto and Proserpine. Accompanying his words with the lyre, he sang his petition for his wife. Without her he would not return. In such tender strains he sang that the very ghosts shed tears. Tantalus, in spite of his thirst, stopped for a moment his efforts for water, Ixion's wheel stood still, the vulture ceased to tear the giant's liver, the daughters of Danaüs rested from their task of drawing water in a sieve, and Sisyphus sat on his rock to listen.156 Then for the first time, it is said, the cheeks of the Furies were wet with tears. Proserpine could not resist and Pluto himself gave way. Eurydice was called. She came from among the new-arrived ghosts, limping with her wounded foot. Orpheus was permitted to take her away with him on condition that he should not turn round to look at her till they should have reached the upper air. Under this condition they proceeded on their way, he leading, she following. Mindful of his promise, without let or hindrance the bard passed through the horrors of hell. All Hades held its breath.

Fig. 94. Farewell of Orpheus and Eurydice

… On he slept,And Cerberus held agape his triple jaws;On stept the bard. Ixion's wheel stood still.Now, past all peril, free was his return,And now was hastening into upper airEurydice, when sudden madness seizedThe incautious lover; pardonable fault,If they below could pardon: on the vergeOf light he stood, and on Eurydice(Mindless of fate, alas! and soul-subdued)Lookt back.There, Orpheus! Orpheus! there was allThy labor shed, there burst the Dynast's bond,And thrice arose that rumor from the lake."Ah, what!" she cried, "what madness hath undoneMe! and, ah, wretched! thee, my Orpheus, too!For lo! the cruel Fates recall me now;Chill slumbers press my swimming eyes… Farewell!Night rolls intense around me as I spreadMy helpless arms … thine, thine no more … to thee."She spake, and, like a vapor, into airFlew, nor beheld him as he claspt the voidAnd sought to speak; in vain; the ferry-guardNow would not row him o'er the lake again,His wife twice lost, what could he? whither go?What chant, what wailing, move the Powers of Hell?Cold in the Stygian bark and lone was she.Beneath a rock o'er Strymon's flood on high,Seven months, seven long-continued months, 'tis said,He breath'd his sorrows in a desert cave,And sooth'd the tiger, moved the oak, with song.157

The Thracian maidens tried their best to captivate him, but he repulsed their advances. Finally, excited by the rites of Bacchus, one of them exclaimed, "See yonder our despiser!" and threw at him her javelin. The weapon, as soon as it came within the sound of his lyre, fell harmless at his feet; so also the stones that they threw at him. But the women, raising a scream, drowned the voice of the music, and overwhelmed him with their missiles. Like maniacs they tore him limb from limb; then cast his head and lyre into the river Hebrus, down which they floated, murmuring sad music to which the shores responded. The Muses buried the fragments of his body at Libethra, where the nightingale is said to sing over his grave more sweetly than in any other part of Greece. His lyre was placed by Jupiter among the stars; but the shade of the bard passed a second time to Tartarus and rejoined Eurydice.

Other mortals who visited the Stygian realm and returned were Hercules, Theseus, Ulysses, and Æneas.158

CHAPTER X

MYTHS OF NEPTUNE, RULER OF THE WATERS

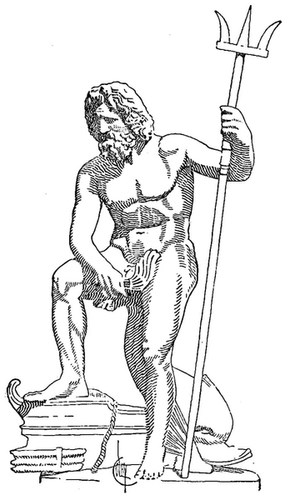

Fig. 95. Poseidon

119. Lord of the Sea. Neptune (Poseidon) was lord both of salt waters and of fresh. The myths that turn on his life as lord of the sea illustrate his defiant invasions of lands belonging to other gods, or his character as earth shaker and earth protector. Of his contests with other gods, that with Minerva for Athens has been related. He contested Corinth with Helios, Argos with Juno, Ægina with Jove, Naxos with Bacchus, and Delphi with Apollo. That he did not always make encroachments in person upon the land that he desired to possess or to punish, but sent some monster instead, will be seen in the myth of Andromeda159 and in the following story of Hesione,160 the daughter of Laomedon of Troy.

Neptune and Apollo had fallen under the displeasure of Jupiter after the overthrow of the giants. They were compelled, it is said, to resign for a season their respective functions and to serve Laomedon, then about to build the city of Troy. They aided the king in erecting the walls of the city but were refused the wages agreed upon. Justly offended, Neptune ravaged the land by floods and sent against it a sea monster, to satiate the appetite of which the desperate Laomedon was driven to offer his daughter Hesione. But Hercules appeared upon the scene, killed the monster, and rescued the maiden. Neptune, however, nursed his wrath; and it was still warm when the Greeks marched against Troy.

Of a like impetuous and ungovernable temper were the sons of Neptune by mortal mothers. From him were sprung the savage Læstrygonians, Orion, the Cyclops Polyphemus, the giant Antæus whom Hercules slew, Procrustes, and many another redoubtable being whose fortunes are elsewhere recounted.161

120. Lord of Streams and Fountains. As earth shaker, the ruler of the deep was known to effect convulsions of nature that made Pluto leap from his throne lest the firmament of the underworld might be falling about his ears. But as god of the streams and fountains, Neptune displayed milder characteristics. When Amymone, sent by her father Danaüs to draw water, was pursued by a satyr, Neptune gave ear to her cry for help, dispatched the satyr, made love to the maiden, and boring the earth with his trident called forth the spring that still bears the Danaïd's name. He loved the goddess Ceres also, through whose pastures his rivers strayed; and Arne the shepherdess, daughter of King Æolus, by whom he became the forefather of the Bœotians. His children, Pelias and Neleus, by the princess Tyro, whom he wooed in the form of her lover Enipeus, became keepers of horses – animals especially dear to Neptune. Perhaps it was the similarity of horse-taming to wave-taming that attracted the god to these quadrupeds; perhaps it was because they increased in beauty and speed on the pastures watered by his streams. It is said, indeed, that the first and fleetest of horses, Arion, was the offspring of Neptune and Ceres, or of Neptune and a Fury.

121. Pelops and Hippodamia. 162 To Pelops, brother of Niobe, Neptune imparted skill in training and driving horses, – and with good effect. For it happened that Pelops fell in love with Hippodamia, daughter of Œnomaüs, king of Elis and son of Mars, – a girl of whom it was reported that none could win her save by worsting the father in a chariot race, and that none might fail in that race and come off alive. Since an oracle, too, had warned Œnomaüs to beware of the future husband of his daughter, he had provided himself with horses whose speed was like the cyclone. But Pelops, obtaining from Neptune winged steeds, entered the race and won it, – whether by the speed of his horses or by the aid of Hippodamia, who, it is said, bribed her father's charioteer, Myrtilus, to take a bolt out of the chariot of Œnomaüs, is uncertain. At any rate, Pelops married Hippodamia. He was so injudicious, however, as to throw Myrtilus into the sea; and from that treachery sprang the misfortunes of the house of Pelops. For Myrtilus, dying, cursed the murderer and his race.

Fig. 96. Pelops winning the Race, Hippodamia looking on

CHAPTER XI

MYTHS OF THE LESSER DIVINITIES OF HEAVEN

122. Myths of Stars and Winds. The tales of Stars and Winds and the other lesser powers of the celestial regions are closely interwoven. That the winds which sweep heaven should kiss the stars is easy to understand. The stories of Aurora (Eos) and of Aura, of Phosphor and of Halcyone, form, therefore, a ready sequence.

Fig. 97. Phosphor, Eos, and Helios (the Sun) rising from the Sea

123. Cephalus and Procris. 163 Aurora, the goddess of the dawn, fell in love with Cephalus, a young huntsman. She stole him away, lavished her love upon him, tried to content him, but in vain. He cared for his young wife Procris more than for the goddess. Finally, Aurora dismissed him in displeasure, saying, "Go, ungrateful mortal, keep thy wife; but thou shalt one day be sorry that thou didst ever see her again."

Cephalus returned and was as happy as before in his wife. She, being a favorite of Diana, had received from her for the chase a dog and a javelin, which she handed over to her husband. Of the dog it is told that when about to catch the swiftest fox in the country, he was changed with his victim into stone. For the heavenly powers, who had made both and rejoiced in the speed of both, were not willing that either should conquer. The javelin was destined to a sad office. It appears that Cephalus, when weary of the chase, was wont to stretch himself in a certain shady nook to enjoy the breeze. Sometimes he would say aloud, "Come, gentle Aura, sweet goddess of the breeze, come and allay the heat that burns me." Some one, foolishly believing that he addressed a maiden, told the secret to Procris. Hoping against hope, she stole out after him the next morning and concealed herself in the place which the informer had indicated. Cephalus, when tired with sport, stretched himself on the green bank and summoned fair Aura as usual. Suddenly he heard, or thought he heard, a sound as of a sob in the bushes. Supposing it to proceed from some wild animal, he threw his javelin at the spot. A cry told him that the weapon had too surely met its mark. He rushed to the place and raised his wounded Procris from the earth. She, at last, opened her feeble eyes and forced herself to utter these words: "I implore thee, if thou hast ever loved me, if I have ever deserved kindness at thy hands, my husband, grant me this last request; marry not that odious Breeze!" So saying, she expired in her lover's arms.

Fig. 98. Sun, rising, preceded by Dawn

From the painting by Guido Reni

Fig. 99. Sunrise; Eos pursuing Cephalus

124. Dobson's The Death of Procris. A different version of the story is given in the following:

Procris, the nymph, had wedded Cephalus; —He, till the spring had warmed to slow-winged daysHeavy with June, untired and amorous,Named her his love; but now, in unknown ways,His heart was gone; and evermore his gazeTurned from her own, and even farther rangedHis woodland war; while she, in dull amaze,Beholding with the hours her husband changed,Sighed for his lost caress, by some hard god estranged.So, on a day, she rose and found him not.Alone, with wet, sad eye, she watched the shadeBrighten below a soft-rayed sun that shotArrows of light through all the deep-leaved glade;Then, with weak hands, she knotted up the braidOf her brown hair, and o'er her shoulders castHer crimson weed; with faltering fingers madeHer golden girdle's clasp to join, and pastDown to the trackless wood, full pale and overcast.And all day long her slight spear devious flew,And harmless swerved her arrows from their aim,For ever, as the ivory bow she drew,Before her ran the still unwounded game.Then, at the last, a hunter's cry there came,And, lo! a hart that panted with the chase.Thereat her cheek was lightened as with flame,And swift she gat her to a leafy place,Thinking, "I yet may chance unseen to see his face."Leaping he went, this hunter Cephalus,Bent in his hand his cornel bow he bare,Supple he was, round-limbed and vigorous,Fleet as his dogs, a lean Laconian pair.He, when he spied the brown of Procris' hairMove in the covert, deeming that apartSome fawn lay hidden, loosed an arrow there;Nor cared to turn and seek the speeded dart,Bounding above the fern, fast following up the hart.But Procris lay among the white wind-flowers,Shot in the throat. From out the little woundThe slow blood drained, as drops in autumn showersDrip from the leaves upon the sodden ground.None saw her die but Lelaps, the swift hound,That watched her dumbly with a wistful fear,Till, at the dawn, the hornèd wood-men foundAnd bore her gently on a sylvan bier,To lie beside the sea, – with many an uncouth tear.125. Ceyx and Halcyone. The son of Aurora and Cephalus was Phosphor, the Star of Morning. His son Ceyx, king of Trachis in Thessaly, had married Halcyone, daughter of Æolus.164 Their reign was happy until the brother of Ceyx met his death. The direful prodigies that followed this event made Ceyx feel that the gods were hostile to him. He thought best therefore to make a voyage to Claros in Ionia to consult the oracle of Apollo. In spite of his wife's entreaties (for as daughter of the god of winds she knew how dreadful a thing a storm at sea was), Ceyx set sail. He was shipwrecked and drowned. His last prayer was that the waves might bear his body to the sight of Halcyone, and that it might receive burial at her hands.

In the meanwhile, Halcyone counted the days till her husband's promised return. To all the gods she offered frequent incense, but more than all to Juno. The goddess, at last, could not bear to be further pleaded with for one already dead. Calling Iris, she enjoined her to approach the drowsy dwelling of Somnus and bid him send a vision to Halcyone in the form of Ceyx, to reveal the sad event.

Fig. 100. The God of Sleep

Iris puts on her robe of many colors, and tinging the sky with her bow, seeks the cave near the Cimmerian country, which is the abode of the dull god, Somnus. Here Phœbus dare not come. Clouds and shadows are exhaled from the ground, and the light glimmers faintly. The cock never there calls aloud to Aurora, nor watchdog nor goose disturbs the silence. No wild beast, nor cattle, nor branch moved with the wind, nor sound of human conversation breaks the stillness. From the bottom of the rock the river Lethe flows, and by its murmur invites to sleep. Poppies grow before the door of the cave, from whose juices Night distills slumbers which she scatters over the darkened earth. There is no gate to creak on its hinges, nor any watchman. In the midst, on a couch of black ebony adorned with black plumes and black curtains the god reclines, his limbs relaxed in sleep. Around him lie dreams, resembling all various forms, as many as the harvest bears stalks, or the forest leaves, or the seashore sand grains.

Brushing away the dreams that hovered around her, Iris lit up the cave and delivered her message to the god, who, scarce opening his eyes, had great difficulty in shaking himself free from himself.

Then Iris hasted away from the drowsiness creeping over her, and returned by her bow as she had come. But Somnus called one of his sons, Morpheus, the most expert in counterfeiting forms of men, to perform the command of Iris; then laid his head on his pillow and yielded himself again to grateful repose.

Morpheus flew on silent wings to the Hæmonian city, where he assumed the form of Ceyx. Pale like a dead man, naked and dripping, he stood before the couch of the wretched wife and told her that the winds of the Ægean had sunk his ship, that he was dead.

Weeping and groaning, Halcyone sprang from sleep and, with the dawn, hastening to the seashore, descried an indistinct object washed to and fro by the waves. As it floated nearer she recognized the body of her husband. In despair, leaping from the mole, she was changed instantly to a bird, and poured forth a song of grief as she flew. By the mercy of the gods Ceyx was likewise transformed. For seven days before and seven days after the winter solstice, Jove forbids the winds to blow. Then Halcyone broods over her nest; then the way is safe to seafarers. Æolus confines the winds that his grandchildren may have peace.

126. Aurora and Tithonus. 165 Aurora seems frequently to have been inspired with the love of mortals. Her greatest favorite, and almost her latest, was Tithonus, son of Laomedon, king of Troy. She stole him away and prevailed on Jupiter to grant him immortality; but forgetting to have youth joined in the gift, after some time she began to discern, to her great mortification, that he was growing old. When his hair was white she left his society; but he still had the range of her palace, lived on ambrosial food, and was clad in celestial raiment. In time he lost the power of using his limbs; and then she shut him up in his chamber, whence his feeble voice might at times be heard. Finally, she turned him into a grasshopper.

127. Tennyson's Tithonus. The following is, according to a fine poetic conception, the lament of the old man when but a white-haired shadow:

The woods decay, the woods decay and fall,The vapors weep their burthen to the ground,Man comes and tills the field and lies beneath,And after many a summer dies the swan.Me only cruel immortalityConsumes: I wither slowly in thine arms,Here at the quiet limit of the world,A white-haired shadow roaming like a dreamThe ever silent spaces of the East,Far-folded mists, and gleaming halls of morn.Alas! for this gray shadow, once a man —So glorious in his beauty and thy choice,Who madest him thy chosen, that he seem'dTo his great heart none other than a God!I ask'd thee, "Give me immortality."Then didst thou grant mine asking with a smile,Like wealthy men who care not how they give;But thy strong Hours indignant work'd their wills,And beat me down and marr'd and wasted me,And tho' they could not end me, left me maim'dTo dwell in presence of immortal youth,Immortal age beside immortal youth,And all I was, in ashes. Can thy love,Thy beauty, make amends, tho' even now,Close over us, the silver star, thy guide,Shines in those tremulous eyes that fill with tearsTo hear me? Let me go: take back thy gift:Why should a man desire in any wayTo vary from the kindly race of men,Or pass beyond the goal of ordinanceWhere all should pause, as is most meet for all?A soft air fans the cloud apart; there comesA glimpse of that dark world where I was born.Once more the old mysterious glimmer stealsFrom thy pure brows, and from thy shoulders pure,And bosom beating with a heart renew'd.Thy cheek begins to redden thro' the gloom,Thy sweet eyes brighten slowly close to mine,Ere yet they blind the stars, and the wild teamWhich love thee, yearning for thy yoke, arise,And shake the darkness from their loosen'd manes,And beat the twilight into flakes of fire.Lo! ever thus thou growest beautifulIn silence, then before thine answer givenDepartest, and thy tears are on my cheek.Why wilt them ever scare me with thy tears,And make me tremble lest a saying learntIn days far-off, on that dark earth, be true?"The gods themselves cannot recall their gifts."Ay me! ay me! with what another heartIn days far-off, and with what other eyesI used to watch – if I be he that watched —The lucid outline forming round thee; sawThe dim curls kindle into sunny rings;Changed with thy mystic change, and felt my bloodGlow with the glow that slowly crimson'd allThy presence and thy portals, while I lay,Mouth, forehead, eyelids, growing dewy-warmWith kisses balmier than half-opening budsOf April, and could hear the lips that kiss'dWhispering I knew not what of wild and sweet,Like that strange song I heard Apollo sing,While Ilion like a mist rose into towers.Yet hold me not forever in thine East:How can my nature longer mix with thine?Coldly thy rosy shadows bathe me, coldAre all thy lights, and cold my wrinkled feetUpon thy glimmering thresholds, when the steamFloats up from those dim fields about the homesOf happy men that have the power to die,And grassy barrows of the happier dead.Release me, and restore me to the ground;Thou seëst all things, thou wilt see my grave:Thou wilt renew thy beauty morn by morn;I earth in earth forget these empty courts,And thee returning on thy silver wheels.128. Memnon, the son of Aurora and Tithonus, was king of the Æthiopians. He went with warriors to assist his kindred in the Trojan War, and was received by King Priam with honor. He fought bravely, slew Antilochus, the brave son of Nestor, and held the Greeks at bay until Achilles appeared. Before that hero he fell.