полная версия

полная версияThe Classic Myths in English Literature and in Art (2nd ed.) (1911)

Psyche, meanwhile, wandered day and night, without food or repose, in search of her husband. But he was lying heartsick in the chamber of his mother; and that goddess was absent upon her own affairs. Then the white sea gull which floats over the waves dived into the middle deep,

And rowing with his glistening wings arrivedAt Aphrodite's bower beneath the sea.She, as yet unaware of her son's mischance, was joyously consorting with her handmaidens; but he, the sea gull,

But he with garrulous and laughing tongueBroke up his news; how Eros fallen sickLay tossing on his bed, to frenzy stungBy such a burn as did but barely prick:A little bleb, no bigger than a pease,Upon his shoulder 'twas, that killed his ease,Fevered his heart, and made his breathing thick."For which disaster hath he not been seenThis many a day at all in any place:And thou, dear mistress," said he, "hast not beenThyself among us now a dreary space:And pining mortals suffer from a dearthOf love; and for this sadness of the earthThy family is darkened with disgrace…"'Tis plain that, if thy pleasure longer pause,Thy mighty rule on earth hath seen its day:The race must come to perish, and no causeBut that thou sittest with thy nymphs at play,While on the Cretan hills thy truant boyHas with his pretty mistress turned to toy,And, less for pain than love, now pines away."128And Venus cried angrily, "My son, then, has a mistress! And it is Psyche, who witched away my beauty and was the rival of my godhead, whom he loves!"

Therewith she issued from the sea, and, returning to her golden chamber, found there the lad sick, as she had heard, and cried from the doorway, "Well done, truly! to trample thy mother's precepts under foot, to spare my enemy that cross of an unworthy love; nay, unite her to thyself, child as thou art, that I might have a daughter-in-law who hates me! I will make thee repent of thy sport, and the savor of thy marriage bitter. There is one who shall chasten this body of thine, put out thy torch, and unstring thy bow. Not till she has plucked forth that hair, into which so oft these hands have smoothed the golden light, and sheared away thy wings, shall I feel the injury done me avenged." And with this she hastened in anger from the doors.

And Ceres and Juno met her, and sought to know the meaning of her troubled countenance. "Ye come in season," she cried; "I pray you, find for me Psyche. It must needs be that ye have heard the disgrace of my house." And they, ignorant of what was done, would have soothed her anger, saying, "What fault, Mistress, hath thy son committed, that thou wouldst destroy the girl he loves? Knowest thou not that he is now of age? Because he wears his years so lightly must he seem to thee ever to be a child? Wilt thou forever thus pry into the pastimes of thy son, always accusing his wantonness, and blaming in him those delicate wiles which are all thine own?" Thus, in secret fear of the boy's bow, did they seek to please him with their gracious patronage. But Venus, angry at their light taking of her wrongs, turned her back upon them, and with hasty steps made her way once more to the sea.129

And soon after, Psyche herself reached the temple of Ceres, where she won the favor of the goddess by arranging in due order the heaps of mingled grain and ears and the carelessly scattered harvest implements that lay there. The holy Ceres then counseled her to submit to Venus, to try humbly to win her forgiveness, and, mayhap, through her favor regain the lover that was lost.

Obeying the commands of Ceres, Psyche took her way to the temple of the golden-crowned Cypris. That goddess received her with angry countenance, called her an undutiful and faithless servant, taunted her with the wound given to her husband, and insisted that for so ill-favored a girl there was no way of meriting a lover save by dint of industry. Thereupon she ordered Psyche to be led to the storehouse of the temple, where was laid up a great quantity of wheat, barley, millet, vetches, beans, and lentils prepared for food for her pigeons, and gave order, "Take and separate all these grains, putting all of the same kind in a parcel by themselves, – and see that thou get it done before evening." This said, Venus departed and left the girl to her task. But Psyche, in perfect consternation at the enormous task, sat stupid and silent; nor would the work have been accomplished had not Cupid stirred up the ants to take compassion on her. They separated the pile, sorting each kind to its parcel and vanishing out of sight in a moment.

At the approach of twilight, Cytherea returned from the banquet of the gods, breathing odors and crowned with roses. Seeing the task done, she promptly exclaimed, "This is no work of thine, wicked one, but his, whom to thine own and his misfortune thou hast enticed," – threw the girl a piece of black bread for her supper, and departed.

Next morning, however, the goddess, ordering Psyche to be summoned, commanded her to fetch a sample of wool gathered from each of the golden-shining sheep that fed beyond a neighboring river. Obediently the princess went to the riverside, prepared to do her best to execute the command. But the god of that stream inspired the reeds with harmonious murmurs that dissuaded her from venturing among the golden rams while they raged under the influence of the rising sun. Psyche, observing the directions of the compassionate river-god, crossed when the noontide sun had driven the cattle to the shade, gathered the woolly gold from the bushes where it was clinging, and returned to Venus with her arms full of the shining fleece. But, far from commending her, that implacable mistress said, "I know very well that by the aid of another thou hast done this; not yet am I assured that thou hast skill to be of use. Here, now, take this box to Proserpine and say, 'My mistress Venus entreats thee to send her a little of thy beauty, for in tending her sick son she hath lost some of her own.'"

Psyche, satisfied that her destruction was at hand, doomed as she was to travel afoot to Erebus, thought to shorten the journey by precipitating herself at once from the summit of a tower. But a voice from the tower, restraining her from this rash purpose, explained how by a certain cave she might reach the realm of Pluto; how she might avoid the peril of the road, pass by Cerberus, and prevail on Charon to take her across the black river and bring her back again. The voice, also, especially cautioned her against prying into the box filled with the beauty of Proserpine.

So, taking heed to her ways, the unfortunate girl traveled safely to the kingdom of Pluto. She was admitted to the palace of Proserpine, where, contenting herself with plain fare instead of the delicious banquet that was offered her, she delivered her message from Venus. Presently the box, filled with the precious commodity, was restored to her; and glad was she to come out once more into the light of day.

But having got so far successfully through her dangerous task, a desire seized her to examine the contents of the box, and to spread the least bit of the divine beauty on her cheeks that she might appear to more advantage in the eyes of her beloved husband.

Therewith down by the wayside did she sitAnd turned the box round, long regarding it;But at the last, with trembling hands, undidThe clasp, and fearfully raised up the lid;But what was there she saw not, for her headFell back, and nothing she rememberèdOf all her life, yet nought of rest she had,The hope of which makes hapless mortals glad;For while her limbs were sunk in deadly sleepMost like to death, over her heart 'gan creepIll dreams; so that for fear and great distressShe would have cried, but in her helplessnessCould open not her mouth, or frame a word.130But Cupid, now recovered from his wound, slipped through a crack in the window of his chamber, flew to the spot where his beloved lay, gathered up the sleep from her body and inclosed it again in the box, then waked Psyche with the touch of an arrow. "Again," said he, "hast thou almost perished by thy curiosity. But now perform the task imposed upon thee by my mother, and I will care for the rest."

Fig. 76. Psyche and Cupid on Mount Olympus

From the painting by Thumann

Then Cupid, swift as lightning penetrating the heights of heaven, presented himself before Jupiter with his supplication. Jupiter lent a favoring ear and pleaded the cause of the lovers with Venus. Gaining her consent, he ordered Mercury to convey Psyche to the heavenly abodes. On her advent, the king of the immortals, handing her a cup of ambrosia, said, "Drink this, Psyche, and be immortal. Thy Cupid shall never break from the knot in which he is tied; these nuptials shall indeed be perpetual."

Thus Psyche was at last united to Cupid; and in due season a daughter was born to them whose name was Pleasure.

The allegory of Cupid and Psyche is well presented in the following lines:

They wove bright fables in the days of old,When reason borrowed fancy's painted wings;When truth's clear river flowed o'er sands of gold,And told in song its high and mystic things!And such the sweet and solemn tale of herThe pilgrim-heart, to whom a dream was given,That led her through the world, – Love's worshiper, —To seek on earth for him whose home was heaven!

EROS WITH BOW

In the full city, – by the haunted fount, —Through the dim grotto's tracery of spars, —'Mid the pine temples, on the moonlit mount,Where silence sits to listen to the stars;In the deep glade where dwells the brooding dove,The painted valley, and the scented air,She heard far echoes of the voice of Love,And found his footsteps' traces everywhere.But never more they met! since doubts and fears,Those phantom-shapes that haunt and blight the earth,Had come 'twixt her, a child of sin and tears,And that bright spirit of immortal birth;Until her pining soul and weeping eyesHad learned to seek him only in the skies;Till wings unto the weary heart were given,And she became Love's angel bride in heaven!131

The story of Cupid and Psyche first appears in the works of Apuleius, a writer of the second century of our era. It is therefore of much more recent date than most of the classic myths.

102. Keats' Ode to Psyche. To this fact allusion is made in the following poem:

O Goddess! hear these tuneless numbers, wrungBy sweet enforcement and remembrance dear,And pardon that thy secrets should be sungEven into thine own soft-conchèd ear:Surely I dreamt to-day, or did I seeThe wingèd Psyche with awakened eyes?I wandered in a forest thoughtlessly,And, on the sudden, fainting with surprise,Saw two fair creatures, couchèd side by sideIn deepest grass, beneath the whispering roofOf leaves and tumbled blossoms, where there ranA brooklet, scarce espied!'Mid hushed, cool-rooted flowers, fragrant-eyed,Blue, silver-white, and budded Tyrian,They lay calm-breathing on the bedded grass;Their arms embracèd, and their pinions, too;Their lips touched not, but had not bade adieu,As if disjoinèd by soft-handed slumber,And ready still past kisses to outnumberAt tender eye-dawn of Aurorean love:The wingèd boy I knew:But who wast thou, O happy, happy dove?His Psyche true!O latest born and loveliest vision farOf all Olympus' faded hierarchy!Fairer than Phœbe's sapphire-regioned star,Or Vesper, amorous glowworm of the sky;Fairer than these, though temple thou hast none,Nor altar heaped with flowers;Nor virgin-choir to make delicious moanUpon the midnight hours;No voice, no lute, no pipe, no incense sweetFrom chain-swung censer teeming;No shrine, no grove, no oracle, no heatOf pale-mouthed prophet dreaming.O brightest! though too late for antique vowsToo, too late for the fond believing lyre,When holy were the haunted forest boughs,Holy the air, the water, and the fire;Yet even in these days so far retiredFrom happy pieties, thy lucent fans,Fluttering among the faint Olympians,I see, and sing, by my own eyes inspired.So let me be thy choir, and make a moanUpon the midnight hours;Thy voice, thy lute, thy pipe, thy incense sweetFrom swingèd censer teeming,Thy shrine, thy grove, thy oracle, thy heatOf pale-mouthed prophet dreaming.Yes, I will be thy priest, and build a faneIn some untrodden region of my mind,Where branchèd thoughts, new grown with pleasant pain,Instead of pines shall murmur in the wind:Far, far around shall those dark clustered treesFledge the wild-ridgèd mountains steep by steep;And there by zephyrs, streams, and birds and bees,The moss-lain Dryads shall be lulled to sleep;And in the midst of this wide quietnessA rosy sanctuary will I dressWith the wreathèd trellis of a working brain,With buds, and bells, and stars without a name,With all the gardener Fancy e'er could feign,Who breeding flowers, will never breed the same;And there shall be for thee all soft delightThat shadowy thought can win,A bright torch, and a casement ope at night,To let the warm Love in!The loves of the devotees of Venus are as the sands of the sea for number. Below are given the fortunes of a few: Hippomenes, Hero, Pygmalion, Pyramus, and Phaon. The favor of the goddess toward Paris, who awarded her the palm of beauty in preference to Juno and Minerva, will occupy our attention in connection with the story of the Trojan War.

Fig. 77. Artemis of Gabii

103. Atalanta's Race. 132 Atalanta, the daughter of Schœneus of Bœotia, had been warned by an oracle that marriage would be fatal to her happiness. Consequently she fled the society of men and devoted herself to the sports of the chase. Fair, fearless, swift, and free, in beauty and in desire she was a Cynthia, – of mortal form and with a woman's heart. To all suitors (for she had many) she made answer: "I will be the prize of him only who shall conquer me in the race; but death must be the penalty of all who try and fail." In spite of this hard condition some would try. Of one such race Hippomenes was to be judge. It was his thought, at first, that these suitors risked too much for a wife. But when he saw Atalanta lay aside her robe for the race with one of them, he changed his mind and began to swell with envy of whomsoever seemed likely to win.

The virgin darted forward. As she ran she looked more beautiful than ever. The breezes gave wings to her feet; her hair flew over her shoulders, and the gay fringe of her garment fluttered behind her. A ruddy hue tinged the whiteness of her skin, such as a crimson curtain casts on a marble wall. Her competitor was distanced and was put to death without mercy. Hippomenes, not daunted by this result, fixed his eyes on the virgin and said, "Why boast of beating those laggards? I offer myself for the contest." Atalanta looked at him with pity in her face and hardly knew whether she would rather conquer so goodly a youth or not. While she hesitated, the spectators grew impatient for the contest and her father prompted her to prepare. Then Hippomenes addressed a prayer to Cypris: "Help me, Venus, for thou hast impelled me." Venus heard and was propitious.

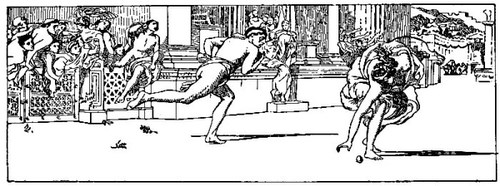

Fig. 78. Atalanta's Race

From the painting by Poynter

She gathered three golden apples from the garden of her temple in her own island of Cyprus and, unseen by any, gave them to Hippomenes, telling him how to use them. Atalanta and her lover were ready. The signal was given.

They both started; he, by one stride, first,For she half pitied him so beautiful,Running to meet his death, yet was resolvedTo conquer: soon she near'd him, and he feltThe rapid and repeated gush of breathBehind his shoulder.From his hand now droptA golden apple: she lookt down and sawA glitter on the grass, yet on she ran.He dropt a second; now she seem'd to stoop:He dropt a third; and now she stoopt indeed:Yet, swifter than a wren picks up a grainOf millet, rais'd her head: it was too late,Only one step, only one breath, too late.Hippomenes had toucht the maple goalWith but two fingers, leaning pronely forth.She stood in mute despair; the prize was won.Now each walkt slowly forward, both so tired,And both alike breathed hard, and stopt at times.When he turn'd round to her, she lowered her faceCover'd with blushes, and held out her hand,The golden apple in it."Leave me now,"Said she, "I must walk homeward."He did takeThe apple and the hand."Both I detain,"Said he, "the other two I dedicateTo the two Powers that soften virgin hearts,Eros and Aphrodite; and this oneTo her who ratifies the nuptial vow."She would have wept to see her father weep;But some God pitied her, and purple wings(What God's were they?) hovered and interposed.133But the oracle was yet to be fulfilled. The lovers, full of their own happiness, after all, forgot to pay due honor to Aphrodite, and the goddess was provoked at their ingratitude. She caused them to give offense to Cybele. That powerful goddess took from them their human form: the huntress heroine, triumphing in the blood of her lovers, she made a lioness; her lord and master a lion, – and yoked them to her car, where they are still to be seen in all representations in statuary or painting of the goddess Cybele.

104 Hero and Leander were star-crossed lovers of later classical fiction.134 Although their story is not of supernatural beings, or of events necessarily influenced by supernatural agencies, and therefore not mythical in the strict sense of the word, it deserves to be included here both because of its pathetic beauty and its long literary tradition. The poet Marlowe puts the story into English thus:

On Hellespont, guilty of true love's blood,In view and opposite two cities stood,Sea-borderers, disjoin'd by Neptune's mightThe one Abydos, the other Sestos hight.At Sestos Hero dwelt; Hero the fair,Whom young Apollo courted for her hair,And offer'd as a dower his burning throne,Where she should sit, for men to gaze upon…Some say, for her the fairest Cupid pin'd,And, looking in her face, was strooken blind.But this is true: so like was one the other,As he imagined Hero was his mother;And oftentimes into her bosom flew,About her naked neck his bare arms threw,And laid his childish head upon her breast,And, with still panting rockt, there took his rest.In Abydos dwelt the manly Leander, who, as luck would have it, bethought himself one day of the festival of Venus in Sestos, and thither fared to do obeisance to the goddess.

On this feast-day, – O cursèd day and hour! —Went Hero through Sestos, from her towerTo Venus' temple, where unhappily,As after chanc'd, they did each other spy.So fair a church as this had Venus none;The walls were of discolored jasper-stone, …And in the midst a silver altar stood:There Hero, sacrificing turtle's blood,Vail'd to the ground, veiling her eyelids close;And modestly they opened as she rose:Thence flew Love's arrow with the golden head;And thus Leander was enamourèd.Stone-still he stood, and evermore he gaz'd,Till with the fire, that from his countenance blaz'd,Relenting Hero's gentle heart was strook:Such power and virtue hath an amorous look.It lies not in our power to love or hate,For will in us is overrul'd by fate.When two are stript long e'er the course begin,We wish that one should lose, the other win;And one especially do we affectOf two gold ingots, like in each respect:The reason no man knows; let it suffice,What we behold is censur'd by our eyes.Where both deliberate, the love is slight:Who ever lov'd, that lov'd not at first sight?He kneel'd; but unto her devoutly prayed:Chaste Hero to herself thus softly said,"Were I the saint he worships, I would hear him";And, as she spake those words, came somewhat near him.He started up; she blush'd as one asham'd;Wherewith Leander much more was inflam'd.He touch'd her hand; in touching it she trembled:Love deeply grounded, hardly is dissembled…So they conversed by touch of hands, till Leander, plucking up courage, began to plead with words, with sighs and tears.

These arguments he us'd, and many more;Wherewith she yielded, that was won before.Hero's looks yielded, but her words made war:Women are won when they begin to jar.Thus having swallow'd Cupid's golden hook,The more she striv'd, the deeper was she strook:Yet, evilly feigning anger, strove she still,And would be thought to grant against her will.So having paus'd awhile, at last she said,"Who taught thee rhetoric to deceive a maid?Ay me! such words as these should I abhor,And yet I like them for the orator."With that Leander stoop'd to have embrac'd her,But from his spreading arms away she cast her,And thus bespake him: "Gentle youth, forbearTo touch the sacred garments which I wear." …Then she told him of the turret by the murmuring sea where all day long she tended Venus' swans and sparrows:

"Come thither." As she spake this, her tongue tripp'd,For unawares, "Come thither," from her slipp'd;And suddenly her former color chang'd,And here and there her eyes through anger rang'd;And, like a planet moving several waysAt one self instant, she, poor soul, assays,Loving, not to love at all, and every partStrove to resist the motions of her heart:And hands so pure, so innocent, nay, suchAs might have made Heaven stoop to have a touch,Did she uphold to Venus, and againVow'd spotless chastity; but all in vain;Cupid beats down her prayers with his wings…

Fig. 79. Hero and Leander

From the painting by Keller

For a season all went well. Guided by a torch which his mistress reared upon the tower, he was wont of nights to swim the strait that he might enjoy her company. But one night a tempest arose and the sea was rough; his strength failed and he was drowned. The waves bore his body to the European shore, where Hero became aware of his death, and in her despair cast herself into the sea and perished.

A picture of the drowning Leander is thus described by Keats:135

Come hither all sweet maidens soberly,Down looking aye, and with a chasten'd light,Hid in the fringe of your eyelids white,And meekly let your fair hands joinèd be,As if so gentle that ye could not see,Untouch'd, a victim of your beauty bright,Sinking away to his young spirit's night,Sinking bewilder'd 'mid the dreary sea:'Tis young Leander toiling to his death;Nigh swooning he doth purse his weary lipsFor Hero's cheek, and smiles against her smile.O horrid dream! see how his body dipsDead-heavy; arms and shoulders gleam awhile;He's gone; up bubbles all his amorous breath!105. Pygmalion and the Statue. 136 Pygmalion saw so much to blame in women, that he came at last to abhor the sex and resolved to live unmarried. He was a sculptor, and had made with wonderful skill a statue of ivory, so beautiful that no living woman was to compare with it. It was indeed the perfect semblance of a maiden that seemed to be alive and that was prevented from moving only by modesty. His art was so perfect that it concealed itself, and its product looked like the workmanship of nature. Pygmalion at last fell in love with his counterfeit creation. Oftentimes he laid his hand upon it as if to assure himself whether it were living or not, and could not even then believe that it was only ivory.

The festival of Venus was at hand, – a festival celebrated with great pomp at Cyprus. Victims were offered, the altars smoked, and the odor of incense filled the air. When Pygmalion had performed his part in the solemnities, he stood before the altar and, according to one of our poets, timidly said:

O Aphrodite, kind and fair,That what thou wilt canst give,Oh, listen to a sculptor's prayer,And bid mine image live!For me the ivory and goldThat clothe her cedar frameAre beautiful, indeed, but cold;Ah, touch them with thy flame!Oh, bid her move those lips of rose,Bid float that golden hair,And let her choose me, as I chose,This fairest of the fair!And then an altar in thy courtI'll offer, decked with gold;And there thy servants shall resort,Thy doves be bought and sold!137According to another version of the story, he said not, "bid mine image live," but "one like my ivory virgin." At any rate, with such a prayer he threw incense on the flame of the altar. Whereupon Venus, as an omen of her favor, caused the flame to shoot up thrice a fiery point into the air.