полная версия

полная версияThe Australian Army Medical Corps in Egypt

3. I shall be glad if you will communicate to the men in the Hospital the fact that comforts are being supplied from the Fund of the British Red Cross Society (Australian Branch), the administration of which fund is in the hands of Surgeon-General W. D. C. Williams, C.B.

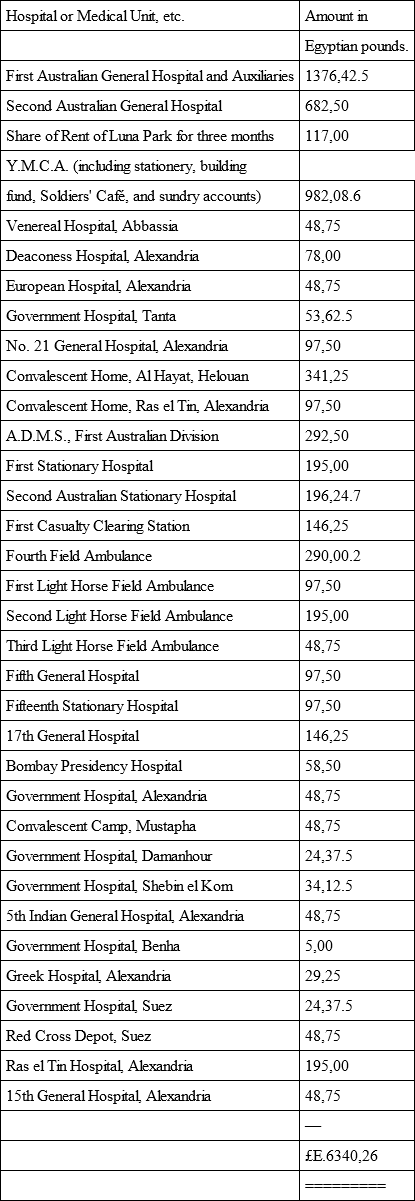

(Signed)James W. Barrett,Major,for W. D. C. Williams,Surgeon-General.Grants of Money made to Various Hospitals from Red Cross Funds

The Egyptian pound is to the British pound sterling as 100:97·5.

In addition, a considerable amount of money had been spent in other countries. There was, however, no knowledge in Egypt of the sum which would be ultimately available. Furthermore, in the absence of instructions from Australia, no serious departure had been made from the policy originally laid down. In fact I am doubtful to a degree whether any Red Cross movement should in normal conditions go beyond the successful policy adopted.

2. Red Cross Store.– Goods received were passed into the Red Cross store, the contents of the cases ascertained as far as possible, and entered in books kept for that purpose. They were issued on requisition signed by the Officer Commanding any medical unit. Corresponding entry was made in the book of issue, and the difference between the stock received and that issued from day to day was shown in the form of a stock sheet. Stock-taking was effected from time to time.

The store was staffed at first by two nurses and three orderlies, later it was staffed by a sergeant and six or seven orderlies who were approved by the military authorities. The staff therefore consisted of myself, with my own clerical staff, the orderly officer of the hospital, Captain Max Yuille (latterly Captain Dunn), the sergeant and seven orderlies, together with extra helpers at times. The store was connected by telephone with the hospital, and every effort made, compatible with the excessive demands on the time of all, to manage it in a methodical manner.

3. Receipt of Goods.– The receipt of goods has, owing to the peculiarities of Egypt and the circumstances of the war, given a good deal of trouble, and I am making it the subject of a separate memorandum. It may suffice here to say that it will never be satisfactory until the Red Cross Society in Australia cables, when the ship leaves Fremantle, precisely the number of packages on board, the port of destination, and the probable time of arrival of the ship; and also accurately informs the officers commanding the ship of the nature of the Red Cross goods on board. In this connection it may be interesting to note the following letter from Colonel Onslow, who has just arrived by the Runic in Egypt, and who, but for the printed instructions drawn up by me and conveyed to him at Suez, would not have known that any Red Cross goods were on board:

Continental Hotel, Cairo,September 13, 1915.Lieut. – Colonel Barrett,

A.A.M.C.

My Dear Sir,

You will remember that on Saturday last you asked me to write to you regarding the Red Cross Stores on the Transport A 54 Runic of which I was in military command.

When I took command on August 9 in Sydney I had no information as to there being any Red Cross Stores on board except that one of the ladies of the Red Cross Committee had told me that a few stores were to be put on board and would be at my disposal if needed for the troops under my command.

Subsequently I saw some half a dozen cases which I assumed to be those to which she had alluded.

On arrival at Suez, September 9, the printed instructions as to disposal of Red Cross Stores were handed to me. This caused me to make inquiries. The ship's purser knew nothing of any such stores and they were not shown in the manifest.

But from the Chief Officer I learned that a large number of which he had an incomplete list had been placed in one of the holds. It was even then too late for me to ascertain their number or nature, as I was in the midst of disembarking returning ship stores, etc. They were therefore landed without the required list.

But if either a wireless had been sent to me a day or two beforehand, or if the persons responsible for shipping had informed me in Sydney, there would have been no difficulty whatever. Under the lack of system which would seem to prevail in shipping these stores from Australia it would not be surprising if they were overcarried and lost.

Yours faithfully,(Signed) J. Macarthur Onslow,Colonel.I publish this letter simply to show the difficulties and to indicate the magnitude of the task. I do not think any one is to blame, but rectification is wanted. A huge commercial concern has gradually grown up and now requires firm paid commercial management. The Australian Red Cross has become a gigantic Commercial Institution with attendant advantages and disadvantages.

It should be remembered that goods are shipped in Australia from at least six different ports separated by distances of hundreds of miles, that nearly the whole of the work has been amateur, and that it is difficult to inaugurate a proper business system rapidly.

The following are the printed directions referred to by Colonel Onslow:

Headquarters, Cairo.From A.D.M.S., Australian Force,

Headquarters, Cairo.

To O.C. Troopship —

1. Will you please instruct a Medical Officer to make a list in duplicate of the surplus medical stores and Red Cross goods, including ambulances, on the ship. He will hand one list to the representative of Australian Intermediate Base (Captain Clayton) and retain the other.

2. Will you please detail a Medical Officer, or if that be impossible another Commissioned Officer, who will see that these goods are put on the train, and travel with them to their point of destination.

3. At the place of destination he will hand them over with an inventory to a representative of A.D.M.S. Australian Force (Lieut. – Colonel Barrett), from whom he will obtain a receipt. He will not, under any circumstances, hand them over to any one else, or take any verbal receipt.

4. If it be impossible to send the goods by passenger train they may proceed by goods train, in which case an N.C.O. or orderly must be detailed to travel in the brake van; and deliver the goods to a representative of A.D.M.S. Australian Force (Lieut. – Colonel Barrett) in precisely the same way.

5. You will please detail a fatigue party of sufficient strength for unloading the goods from the transport and placing them on the train, and in addition supply any guard that is necessary to protect them until this work is completed.

6. It is undesirable in any circumstances to send goods by troop train. It is much better to send them by goods train.

7. Will you please convey these orders in writing to the Medical Officer or Officer concerned. If any conflicting orders be issued he can then produce this authority.

A.D.M.S. Australian Force.4. Distribution of Goods.– The distribution of goods was effected on requisition signed by the O.C. of the medical unit requiring them, transport was provided by the Red Cross Society to the railway station (usually by motor lorries) and at public expense on the railways. I soon learnt that in Egypt in time of war there is no certainty of the delivery of the goods to the proper quarter unless some one is sent with them. The railway officials will frequently hand over goods to a military officer without obtaining a receipt. Accordingly one or more orderlies were sent with every train conveying Red Cross goods. They handed the goods to the consignee and brought back the receipt.

In the Australian hospitals the distribution of goods was effected by two methods. Anything wanted from the central store could be obtained by requisition signed by the O.C. of the hospital, and countersigned by myself as Red Cross officer. Very large quantities of goods were thus transferred from the central store to the quartermaster's department. They were then issued in the ordinary way by requisition of the sisters or medical officers, and those receiving them were not aware whether they were receiving Red Cross goods or Ordnance goods. The system had the merit of extreme simplicity, and was very speedy in its operation. It certainly seemed at the time far less important that patients should know where the goods came from than that they should obtain them promptly. Later on the expediency of putting a Red Cross label on everything supplied became obvious and was adopted as a policy.

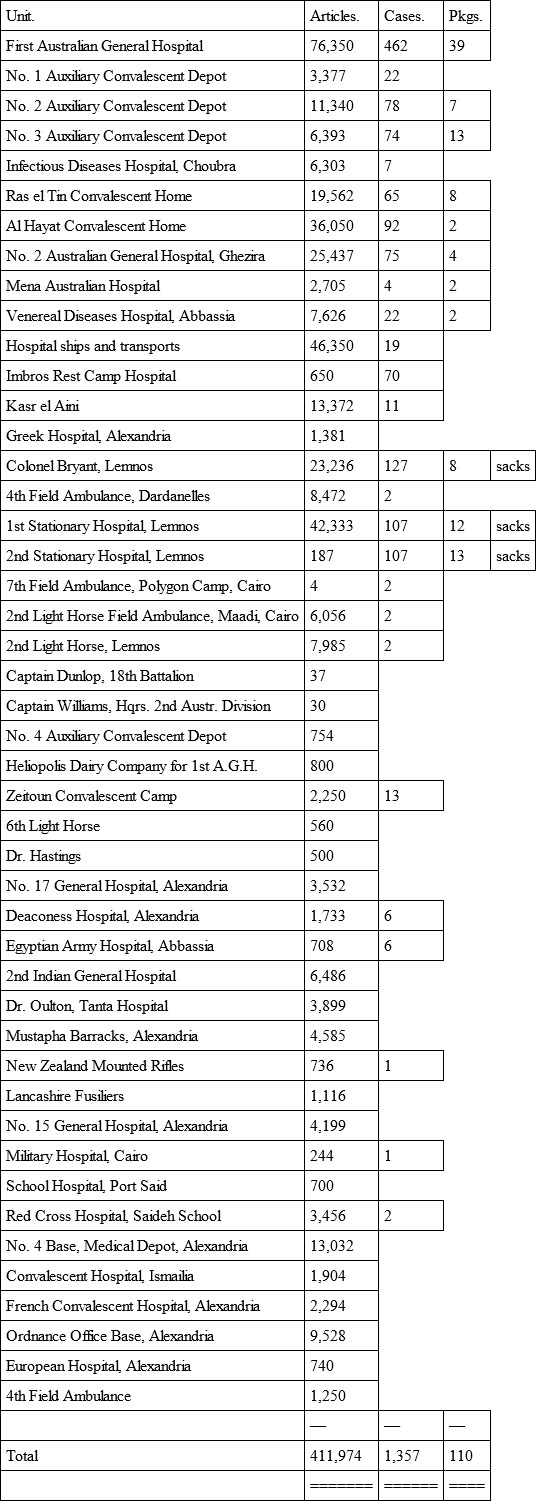

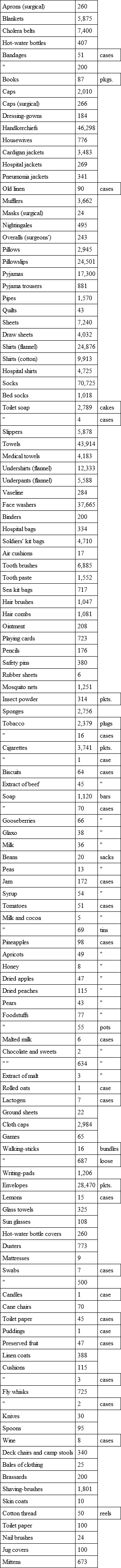

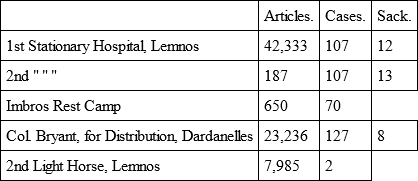

5. Scope of Operations.– At first the operations of the Society were confined to Egypt, but soon, in conjunction with the British Red Cross, goods were forwarded to the Dardanelles and elsewhere. The tables show the quantity of goods sent to transports in the Mediterranean and transports leaving for Australia. No request was ever refused. When dispatching goods to the Dardanelles it was considered better to act, as far as possible, through the British Red Cross Society.

On July 5 I wrote to General Birdwood, Commanding Officer A. and N.Z. Army Corps, asking him whether I could establish a Red Cross store at Anzac. He replied that it was impossible, but at his suggestion a Red Cross store at Mudros in the island of Lemnos was organised in conjunction with the British Red Cross Society. The Army Medical Corps at Anzac was then advised to requisition on Mudros. The difficulties, however, of landing goods at Mudros were very great – so great that the British Red Cross Society was compelled to buy launches and lighters. The Australian Red Cross Commissioners are about to supplement the purchase. The tables show the quantity and character of the goods sent forward in spite of many difficulties. It was often necessary to send an orderly in the hospital ship to Mudros and Anzac to ensure delivery.

6. Other Activities.– The British Red Cross Australian Branch arranged through the Y.M.C.A. for the free distribution of stationery to the soldiers in hospitals in Egypt. With the assistance of the Y.M.C.A. and some English ladies in Cairo a number of committees were formed to entertain the sick and wounded in various ways. A cinema was purchased, a small orchestra was engaged to visit the hospitals, bands of ladies agreed to take flowers and the like to the hospitals, and everything was done that could be done to render the tedium of convalescence less objectionable.

Large recreation huts were built at many of the hospitals at the expense of the Australian Branch.

This phase of the work should not be passed over without the most handsome acknowledgment to the English ladies in Cairo. These public-spirited ladies, headed by Mrs. Elgood, thoroughly organised what I may call the lighter side of hospital work, and not only by their personal attention, but also by their tactful skill, succeeded in making the conditions of the sick and wounded much more comfortable. Furthermore although we left Australia knowing that the Y.M.C.A. did good work in camps, yet the practical experience of the Y.M.C.A. work in Egypt has left an indelible impression on our minds. Headed by Mr. Jessop, their secretary, there was no service in connection with the sick and wounded which they failed to render when provided with the proper means. We felt the utmost confidence in entrusting them with any undertaking, provided that the position was clearly defined and provided that they were not hampered in their activities.

In passing it may be said that until June 15 the shortage of nurses and medical officers was considerable. Of lay helpers there were few in Cairo during the summer, and the principle was invariably adopted of using all existing agencies to cover the ground, the necessary support being given by the Red Cross Society. It was on this principle that Mrs. Elgood acted, it was on this principle that the Y.M.C.A. acted, and it is on this principle that all great organisations can be most successfully conducted. If it had become necessary to create an independent organisation to provide cinemas and bands, to disburse stationery in Egypt and at the Dardanelles, distribute flowers, fruit, games, etc., a very large number of soldiers would have been employed who were much better employed otherwise. Furthermore, they would not have done the work as well as Mrs. Elgood's staff or the Y.M.C.A.

7. Issue of Purchased Goods.– As the fund grew in volume it was decided to spend some of it in the purchase of articles desired by the men. A vote was taken at No. 1 Auxiliary Convalescent Depot (Luna Park) to ascertain the articles the men most desired – see appendix. Boxes containing a number of articles were issued to every patient on admission. This has involved an expenditure rising to £500 per month. A sample box has already been sent to Australia. In each box the following note was placed:

"The object of the Australian Red Cross Society is to provide comfort and help to the wounded and sick soldiers, such as hospital clothing, invalid comforts, tobacco, toilet necessaries, books, magazines, newspapers, and the like, and also recreation huts for entertainment, etc.

"These comforts are supplied over and above the hospital necessaries which the Commonwealth of Australia furnishes on so liberal a scale.

"The Society hopes that your stay in the hospital will be short and pleasant, and that your convalescence will be rapid so that you can speedily serve your country again. The Society asks you to accept the contents of this box as an indication of Australia's desire to help you."

8. Convalescent Home at Montazah.– The Montazah palace, which was owned by the late Khedive, was offered to Lady Graham by H.H. the Sultan as a Convalescent Home for soldiers. The British Red Cross Society and the Australian Branch combined and agreed to find £3,500 to equip it. This beautiful hospital consists of a number of buildings situated on the shore of the Mediterranean, with artificial harbours and provision for bathing, fishing, and boating. It is now in excellent order and is most successful.

While I think it was right to take a share in the erection of this convalescent home, which indeed could not have been obtained as a military hospital, it immediately raised in mind the consideration of the propriety of the Red Cross conducting hospitals in any circumstances. It is of course the English practice, and the special circumstances of Great Britain may make it necessary to erect Red Cross hospitals. The Commonwealth of Australia has never prevented the establishment of as many hospitals as may be considered necessary in the field. In my judgment it is better to limit the conduct of military hospitals and convalescent hospitals to official authority, leaving the Red Cross to supplement the work in the way already indicated. Otherwise the Red Cross is simply doing Governmental work. The Red Cross may do the work very well indeed, but the advantage is not obvious.

9. Motor Transport.– The motor ambulances presented by the Australian Branch have been housed in two garages, one at Heliopolis and the other at Gezira. They were both designed by Surgeon-General Williams and provided from Red Cross Funds. It is not too much to say that the organisation of the motor transport assisted materially in saving the position. For a long time, with the exception of some New Zealand ambulances, there were no other ambulances in Egypt. At Heliopolis a repairing plant was installed at Red Cross expense in order to reduce the cost of repairs.

There is no doubt that the British Red Cross Australian Branch was at the outset of exceptional service because it possessed on the spot stores, money, and motor transport.

10. Bureau of Inquiry.– The British Red Cross Society instituted a bureau of inquiry in order to obtain supplemental information about the sick and wounded. Inquiries on an elaborate scale are made at the office of the Commonwealth Government, but certain supplementary and private inquiries can be made with profit. The British Red Cross Society was requested to undertake such inquiries and to charge Australian Red Cross for the extra assistance necessitated.

11. Hospital Trains.– At an early stage steps were taken to equip hospital trains running from Alexandria to Cairo with everything the officers in charge required.

Furthermore, arrangements were made at Red Cross expense to provide a restaurant car on all trains conveying sick and wounded to Suez. For detailed arrangements see page 166. This arrangement has proved of great benefit. The men obtained free lime juice and water and their rations. They could purchase in addition comforts at bed-rock prices. The innovation may seem a small one, but it was not effected without considerable trouble owing to shortage of rolling stock.

List of Red Cross Goods issued to Units fromend of March to September 3, 1915Prepared by Staff-Sergeant Hudson

1. The Restaurant Car can be placed on the train and the cost of same, £7 10s., guaranteed by Lieut. Colonel Barrett.

2. Meals will be provided for Commissioned Officers, P.T. 20 lunch or dinner, P.T. 5 afternoon tea, at stated times.

3. Meals and afternoon tea will be provided for N.C.O.s in the Restaurant Car at half price.

4. Sandwiches, P.T. 1, and non-alcoholic drinks (soda water, lemonade, etc.), P.T. 1, will be served in the cars by the attendants of the Restaurant Car to soldiers who desire to purchase them.

5. In addition, water will be provided in each carriage for the use of soldiers in fantasses, and lime juice will be supplied, two bottles in each carriage, free.

Notice to this effect will be posted in every carriage on the troop train.

July 1, 1915.

12. Soldiers' Clubs.– Reference has been made in the chapter on Venereal Diseases to the damage done to Australian troops in Egypt by venereal disease. Reference has also been made to the establishment of soldiers' clubs and recreation huts in various places to provide a counter-attraction to those entertainments furnished by the prostitute and her degraded male attendants. After the various repressive steps already referred to had been taken, an earnest attempt was made to organise this constructive work. The valuable assistance of Mr. Jessop and the Y.M.C.A. was again invited. The Y.M.C.A. proposed to build in Alexandria on the sea front a large building to be used as a central soldiers' club, and to be available for convalescents and the healthy. The Y.M.C.A. had only £250 available and required £1,000. The British Red Cross Society was appealed to and hesitated. A cable was dispatched to London, and an expenditure of £250 authorised. Surgeon-General Williams, after consultation with His Excellency Sir Henry MacMahon, the G.O.C. – in-Chief, Sir John Maxwell, and the D.M.S. Egypt, General Ford, decided to make a grant of £500 in addition for the purpose. The club was opened on September 12, and from its opening was a pronounced success. The soldier on leave, tramping about the streets of Alexandria, gets leg-weary and falls an easy victim to the wiles of the various agents abroad. He now can visit his own club, where the entry is free to all men in uniform. He there receives war telegrams, stationery, cheap and excellent meals, and enjoys various forms of entertainment. He meets his friends, and can spend the time under the most pleasant conditions. The building already requires extension, as the pressure on the accommodation is so great. Similar action was taken in Cairo, where after many unsuccessful attempts the Rink Theatre in the beautiful Esbekieh gardens was obtained, owing to the sympathetic help given by His Excellency Sir Henry MacMahon and other authorities. This open-air theatre is a little over an acre in extent, and is a valuable property. It had been leased to a restaurant keeper in the vicinity. Arrangements were made for the supply of light refreshments at bed-rock prices in the theatre, and other meals at low prices at the restaurant which is about fifty yards away. In addition a soldiers' club, managed by ladies, is equidistant, and at this comfortable resort refreshments are supplied in quiet rooms at low rates. Naturally the club has become a resort for all the soldiers in Cairo. Major Harvey, Commissioner of Police, has cleared the surrounding gardens of undesirable characters. The club was placed under the management of a joint committee of which Her Excellency Lady MacMahon is Patroness, and Lady Maxwell is President. The executive committee consists of three members of the Y.M.C.A., and the expenses of managing the club were provided by the British Red Cross Society, Australian Branch, for the first three months. It was soon found that in order to make the club successful the athletic element must be developed, and splendid programmes were arranged – boxing, fencing, skating contests, and the like. The club provides writing-paper, games, war telegrams, Australian and other newspapers, shower baths, and other conveniences. As many as 1,500 soldiers are present on some of these occasions, and the club is visited by officers who periodically drop in amongst the men. Altogether the success has exceeded even the sanguine expectations of those who founded it.

The British Red Cross Society, Australian Branch, was most fortunate in securing such a site, as any one acquainted with the conditions of Cairo is fully aware.

The exact extent to which these clubs have contributed to the limitation of venereal disease cannot be accurately measured, but there is no doubt whatever in the minds of any one acquainted with the facts respecting their salutary and healthy influence. Under the new constitution of the Australian Red Cross money cannot be devoted to their maintenance, because it is not being used exclusively for the sick and wounded. Such is the ruling, although many convalescents use the clubs. It is regrettable that such a rigid ruling should have been established. It is absurd to permit men to become infected and then to assist them by doles of chocolate and tobacco, and yet to refuse to provide the necessary funds which assist so materially in preventing infection.

13. Nurses' Rest Homes.– The nurses in the hospitals had done excellent work under trying conditions, and it became obvious that many of them would break down unless holidays and rest were provided.

The British and Australian Red Cross Branches combined under the Presidency of Her Excellency Lady MacMahon, and opened two rest homes – one in Ramleh near the beach, and the other at Aboukir Bay, the site of Nelson's victory.

They were furnished by the Red Cross Societies and have been maintained by the Commonwealth Government so far as the Australian nurses are concerned. They have met a great want and have proved a boon and a blessing.

Conclusion.– The work has been very heavy and the circumstances far from easy. Taking everything into consideration and realising the pressure at both ends, the result can only be regarded as more than satisfactory. The policy of the Red Cross Society requires, however, some consideration.

The policy adopted until lately was that reasonable intimation should be given to the Red Cross Society of the requirements of those who want help. Under public pressure another policy may make its appearance – that of compelling the Red Cross Society to find out what people want. A word of caution is necessary. This policy will almost certainly result in the creation of an extensive business organisation and in the Red Cross undertaking much work which the Government should do. In my opinion the Red Cross Society is entirely ancillary, its functions being to provide comforts and other things which the Government cannot supply, and to act decisively at critical moments. It should, however, refrain from embarking on great national undertakings.

Every one will endeavour to help the Commissioners in their extensive and difficult task, and will look forward to the Australian Red Cross maintaining the high reputation which it has already gained amongst responsible officers in Egypt.