полная версия

полная версияThe Australian Army Medical Corps in Egypt

In the First Australian General Hospital every care was taken to minimise the inconvenience; a very large number of excellent ice chests were purchased, an enormous quantity of ice was used, and the necessary steps thus taken to diminish the amount of food decomposition and prevent ptomaine poisoning. Fans and punkahs were used, and the nights were quite tolerable.

Medical Organisation in EgyptWhen the Australian forces pass three miles from Australian shores they cease, at all events technically, to be under Australian control, and pass under the control of the Commander-in-Chief. On arrival in Egypt they passed under the control of General Sir John Maxwell, G.O.C. – in-Chief, Egypt. The medical section passed under the command of the Director of Medical Services, Surgeon-General Ford. The D.M.S. Australian Imperial Force, Surgeon-General Williams, arrived in Egypt in February and was placed on the staff of General Ford to assist in managing these units. He left for London on duty on April 25, and one of us (J. W. B.) was appointed A.D.M.S. for the Australian Force in Egypt on the staff of General Ford. Later, Colonel Manifold, I.M.S., was appointed D.D.M.S. for Australian and other medical units. Thus the Australian medical units were under the same command as New Zealand or British units, but with separate intermediaries.

The Risk of CholeraIn view of the risk of cholera, the following note by Dr. Armand Ruffer, C.M.G., President of the Sanitary, Maritime and Quarantine Council of Egypt, Alexandria, was issued and, later on, inoculation was practised on an extensive scale.

Dr. Ruffer's Views on Cholera(Report begins) "The first point is that although, in many epidemics, cholera has been a water-borne disease, yet a severe epidemic may occur without any general infection of the water supply. This was clearly the case in the last epidemic in Alexandria. Attention to the water supply, therefore, may not altogether prevent an epidemic. The second point is that the vibrio of cholera may be present in a virulent condition in people showing no, or very slight symptoms of cholera, e. g. people with slight diarrhœa, etc.

The segregation of actual cases of cholera, therefore, is not likely to be followed by any degree of success, because this measure would not touch carriers or mild cases, unless orders were given to consider as contacts all foreign foes, and all soldiers who have been in contact with them. This is clearly impossible.

There cannot be any reasonable doubt, therefore, that if the Turkish army becomes infected with cholera, the British Army will undoubtedly become infected also.

Undoubtedly inoculation is the cheapest and quickest way of protection of the troops, provided this process confers immunity against cholera.

It is very difficult to estimate accurately the protection given by inoculation against cholera. My impression from reading the literature on the subject is that: (1) The inoculations must be done at least twice. (2) The inoculations, if properly made, are harmless as a rule. (3) The inoculations confer a certain protection against cholera. I may add that I arrived at this opinion before the war, when the French editors, Messrs. Masson & Co., asked me to write the article "Cholera" for the French standard textbook on pathology. My opinion was therefore quite unprejudiced by the present circumstances.

The cholera inoculations were harmless as a rule; that is, they were not always harmless. Savas has described certain cases of fulminating cholera amongst people inoculated during the progress of an epidemic. In my opinion, the people so affected were in the period of incubation when they were inoculated, and the operation gave an extra stimulus, so to speak, to the dormant vibrio. One knows that, experimentally, a small dose of toxin, given immediately after or before the inoculation of the microorganism producing the toxin, renders this microorganism more virulent.

The conclusion to be drawn is that inoculations should be carried out before cholera breaks out.

I am afraid I know of no certain facts to guide me in estimating the length of the period of immunity produced by inoculations. Judging by analogy, I should say that it is certainly not less than six months, that it, almost certainly, lasts for one year, and very probably lasts far longer.

I understand that 90,000 doses of cholera vaccine have been sent from London. I take it that the inoculation material has been standardised and its effects investigated, but, in any case, I consider that a few very carefully performed experiments should be undertaken at once in Egypt, in order to make sure of the exact method of administration to be adopted under present conditions.

Probably, a good deal may be done by the timely exhibition of drugs, such as phenacetin, etc., to mitigate the more or less unpleasant effects of preventive inoculation.

As I am on this subject, may I point out the necessity of establishing at the front a laboratory for the early diagnosis of cholera and of dysentery. Cholera has appeared in the last three wars in which Turkey has been engaged, and therefore the chances of the peninsula of Gallipoli becoming infected are great. The early diagnosis of cases of cholera, especially when slight, is extremely difficult and often can be settled by bacteriological examination only.

There never has been a war without dysentery, and almost surely our troops will be infected in time, if they are not already infected. But whereas in previous wars the treatment of dysentery was not specific, the physician is now in possession of rapid methods of treatment, provided he can tell what kind of dysentery (bacillary or amœbic or mixed) he is dealing with.

This differential diagnosis is a hopeless task unless controlled at every step by microscopical and bacteriological examination.

The French are keenly aware of this fact, so much so that they have sent, for that very purpose, three skilled bacteriologists, two of whom are former assistants at the Pasteur Institute, to the Gallipoli Peninsula" (Report ends).

Other Infectious DiseasesThe Infectious Diseases Hospitals were filled mostly with cases of measles and its complications, including severe otitis media. Cases of erysipelas, scarlatina, scabies, and diphtheria were met with in small numbers. In the autumn there was a severe epidemic of mumps.

Through the summer and autumn many cases of diarrhœa and of both amœbic and bacillary dysentery made their appearance. There is good ground for believing that many so-called diarrhœal cases were dysenteric.

There is little doubt short of absolute scientific proof that the greater part of the intestinal diseases are fly borne.

The following table shows the admissions into the hospital, the deaths, and causes of death, to July 31, 1915.

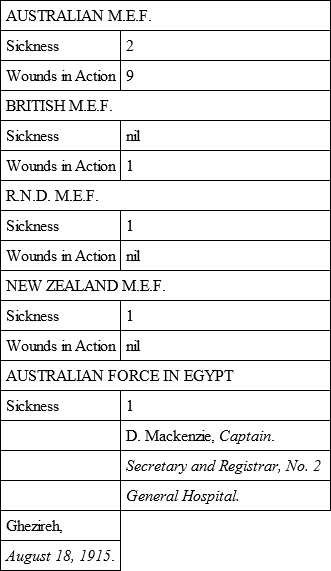

A subsequent table shows the deaths and causes of death in No. 2 Australian General Hospital from May 3 to August 18.

Admissions and Deaths into No. 1 AustralianGeneral HospitalFrom February to July inclusive

In May and June 5,512 men were admitted, of whom 1,219 were Australians and New Zealanders in camp, 2,967 Australians and New Zealanders from the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, 1,050 British, and 276 Naval Division from the same force.

Australian Imperial ForceReturn showing Number of Deaths at No. 2Australian General Hospital, GhezirehFrom May 3, 1915, to August 18, 1915

This chapter would be incomplete unless proper acknowledgment were made of the most valuable post mortem demonstrations given by Major Watson.

CHAPTER VIII

VENEREAL DISEASES – THE GREATEST PROBLEM OF CAMP LIFE IN EGYPT – CONDITIONS IN CAIRO – METHODS TAKEN TO LIMIT INFECTION – MILITARY AND MEDICAL PRECAUTIONS – SOLDIERS' CLUBS.

CHAPTER VIIIThe venereal-disease problem has given a great deal of trouble in Egypt as elsewhere. The problem in Egypt does not differ materially from the problem anywhere else, but a number of fine soldiers have been disabled more or less permanently.

When the First Australian Division landed in Egypt and camped at Mena, the novelty of the surroundings and the lack of intuitive discipline resulted in somewhat of an outbreak, both with regard to conduct and to sexual matters. Both of these phases have been greatly exaggerated, but nevertheless there was substantial ground for apprehension, and the following letter from General Birdwood, Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Army Corps, to the officers commanding units was sufficient evidence of the necessity for action.

"For Private Circulation only"Divisional Headquarters, Mena,"December 18, 1914."The following letter written by Major-General W. R. Birdwood, C.B., C.S.I., C.I.E., D.S.O., Commanding the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, to Major-General W. T. Bridges, C.M.G., Commanding the First Australian Division, has been printed for private circulation.

"V. C. M. SELLHEIM,"Colonel, A.A. and Q.M.G.""HEADQUARTERS: AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND ARMY CORPS,"SHEPHEARD'S HOTEL, CAIRO,"December 27, 1914."MY DEAR GENERAL,

"You will, I know, not misunderstand me if I write to you about the behaviour of a very small proportion of our contingents in Cairo, as I know well that not only you, but all your officers and non-commissioned officers and nearly all the men must be of one mind in wishing only for the good name of our contingents.

"Sir John Maxwell had to write recently complaining of the drunkenness of some of our men in the Cairo streets. During Christmas time some small licence might perhaps have been anticipated, but that time is now over, and I still hear of many cases of drunkenness, and this the men must stop.

"I advisedly say 'the men must stop,' because I feel it is up to the men themselves to put a stop to it by their own good feeling. I wonder if they fully realise that only a few days' sailing from us our fellow-countrymen are fighting for their lives, and fighting as we have never had to do before, simply because they know the very existence of their country is at stake as the result of their efforts.

"We have been given some breathing time here by Lord Kitchener for one object, and one object only – to do our best to fit ourselves to join in the struggle to the best advantage of our country. I honestly do not think that all of our men realise that this is the case. Cairo is full of temptations, and a few of the men seem to think they have come here for a huge picnic; they have money and wish to get rid of it. The worst of it is that Cairo is full of some, probably, of the most unscrupulous people in the world, who are only too anxious to do all they can to entice our boys into the worst of places, and possibly drug them there, only to turn them out again in a short time to bring disgrace on the rest of us.

"Surely the good feeling of the men as a whole must be sufficient to stop this when they realise it. The breathing time we have left us is but a short one and we want every single minute of it to try and make ourselves efficient. We have to remember too that our Governments of the Commonwealth and Dominion have sent us here at a great sacrifice to themselves, and they fully rely on us upholding their good name, and indeed doing much more than that, for I know they look to us to prove that these two contingents contain the finest troops in the British Empire (whose deeds are going down in history), whom they look forward to welcome with all honours when we have done our share, and I hope even more than our share, in ensuring victory over a people who would take all we hold dear from us if we do not crush them now.

"But there is no possibility whatever of our doing ourselves full justice unless we are every one of us absolutely physically fit, and this no man can possibly be if he allows his body to become sodden with drink or rotten from women, and unless he is doing his best to keep himself efficient he is swindling the Government which has sent him to represent it and fight for it. From perhaps a selfish point of view, too, but in the interests of our children and children's children, it is as necessary to keep a 'clean Australia' as a 'White Australia.'

"A very few men can take away our good name. Will you appeal to all to realise what is before us, and from now onwards to keep before them one thought and only one thought until this war is finished with honour – that is, a fixed determination to think of nothing and to work for nothing but their individual efficiency to meet the enemy.

"If the men themselves will let any who do not stick to this know what curs they think them in shirking the work for which it has been their privilege to be selected, then, I know well, any backslidings will stop at once – not from thoughts of punishments, but from good feeling, which is what we want.

"I have just been writing to Lord Kitchener telling him how intensely proud and well-nigh overwhelmed I feel at finding myself in command of such a magnificent body of men as we have here; no man could feel otherwise. He will, I know, follow every movement of ours with unfailing interest, and surely we will never risk disappointing him by allowing a few of our men to give us a bad name. This applies equally to every one of us, from General down to the last-joined Drummer.

"Will you and your men see to it?

"Yours very sincerely,"W. R. Birdwood."Those who possessed any experience of life could not but realise that 18,000 particularly vigorous fine men, brought up in a country where discipline is conspicuous by its absence, and landed for the first time in a semi-eastern city such as Cairo, were likely to behave in such a manner that a small minority would get into trouble. Active steps were taken to meet the difficulties, and to prevent recurrence of the outbreaks when the Second Division and other reinforcements arrived.

General Birdwood accordingly issued the following circular:

"Warning to Soldiers respecting Venereal Disease"Venereal diseases are very prevalent in Egypt. They are already responsible for a material lessening of the efficiency of the Australasian Imperial Forces, since those who are severely infected are no longer fit to serve. A considerable number of soldiers so infected are now being returned to Australia invalided, and in disgrace. One death from syphilis has already occurred.

"Intercourse with public women is almost certain to be followed by disaster. The soldier is therefore asked to consider the matter from several points of view. In the first place if he is infected he will not be efficient and he may be discharged. But the evil does not cease even with the termination of his military career, for he is liable to infect his future wife and children.

"Soldiers are also urged to abstain from the consumption of any native alcoholic beverage offered to them for sale.

"These beverages are nearly always adulterated, and it is said that the mixture offered for sale is often composed of pure alcohol and other ingredients, including urine, and certainly produces serious consequences to those who consume it. As these drinks are drugged, a very small amount is sufficient to make a man absolutely irresponsible for his actions.

"The General Commanding the Australasian Forces, therefore, asks each soldier to realise that on him rests the reputation of the Australasian Force, and he is urged at all costs and hazards to avoid the risk of contracting venereal disease or disgracing himself by drink."

This leaflet was entrusted to Lieut. – Col. Barrett to deliver to troops on arrival, and he accordingly visited Port Said and Suez, interviewed the officers on the transports, and fully explained the position to them. They were requested to use their influence with the men in the direction of restraint. Subsequently after the destruction of the Konigsberg the transports began to arrive at irregular intervals and it became impossible to meet the officers at the ports. They were then interviewed at Abbassia or Heliopolis, and later still by order of General Spens, G.O.C. Training Depot, the men themselves were addressed on the day of their arrival. The form of address was simple. The dangers of infection were pointed out to them – particularly as regards typhoid fever, dysentery, bilharzia, and venereal disease. They were shown how the first three diseases could be avoided. So far as venereal disease was concerned they were informed that the matter was in their own hands. They were asked to imitate the Japanese, and by their own efforts preserve their health with the same care that they bestowed on their rifles or their ammunition, the preservation of health and arms being equally important. Passages from the famous rescript of the Emperor of Japan before the Russian war were quoted in which it was stated in substance that if the normal proportion of sick existed in the Japanese army defeat was a practical certainty; but that if they followed the direction of their medical officers and took the same care of their bodies as they took of their equipment, the number of troops saved thereby would make all the difference in the ensuing conflict.

General Birdwood asked for the whole-hearted and enthusiastic co-operation of all officers in doing their best to control their men, and to prevent them from exposing themselves to the risk of venereal disease. Some little time before the issue of the circular 3 per cent. of the Force were affected by venereal disease on any one day. Fortunately, as a result of the efforts made, the tendency was to diminution, but the amount of venereal disease was still sufficiently great to give concern and anxiety.

There is no doubt that the action of General Birdwood prevented outbreaks and limited the amount of disease. It is also equally true that in spite of his efforts the amount of disease was too large to be contemplated with equanimity.

The Venereal Diseases Hospital, Abbassia, was nearly always full, but from time to time drafts of men were sent back to Australia. One draft of 450 soldiers was sent to Malta early in the campaign. The principle involved in the policy of returning them to Australia was as follows. In Egypt they were useless as soldiers, whether suffering from gonorrhœa or syphilis. They required a large number of medical men and attendants to take care of them. They knew they had disgraced themselves and were a source of trouble to every one concerned. On shipboard they could not get into trouble. They were more likely to be cured, and could then be returned to Egypt, and if not cured could be treated in Australia at leisure. Against this policy the argument was used that diseases were being introduced into Australia, but as a matter of fact a minority of the men suffering from venereal disease brought it from Australia to Egypt. They arrived at Suez suffering from gonorrhœa contracted in some cases at Fremantle. Furthermore the business of those conducting the campaign was to wage a successful war, and to keep the base as free from encumbrance as possible. The total number returned to Australia in this way was as follows:

From February to September 14, 1,344, and in addition 450 were sent to Malta.

At first they were sent in ships with other cases and sometimes segregated on board, but difficulties arose at the Australian ports. The people who welcomed the returned soldiers were sometimes enthusiastic in greeting venereal cases by mistake, and sometimes non-venereal cases were regarded with suspicion because they came from a ship known to convey venereal patients. It was finally decided by the Australian Government that venereal cases should be conveyed in ships by themselves, the first consignment of 369 being sent in the Port Lincoln.

A certain number of the gonorrhœal cases recovered and became fit for service, but too often they relapsed.

The authorities were fully alive to the damage which was being done, and persistent and earnest attempts were made to deal with it from many different points of view. General Maxwell issued an order prohibiting the sale of drink after an early hour (10 p.m.) in the evening, and also prohibiting soldiers from being found in Cairo after an early hour. There is no doubt that both of these directions proved to be of considerable value.

Moral Conditions in CairoSomething must be said, however, about the moral conditions in Cairo, about which exaggerated and perverse notions seem to be entertained. Cairo, like all large cities in the world, possesses its quota of prostitutes, who differ only from prostitutes elsewhere in that the quarters are dirtier and that the women are practically of all nationalities, except English. The quarter in which they live is evil-smelling, and is provided with narrow streets and objectionable places of entertainment. It contains a considerable infusion of Eastern musicians and the like, and is plentifully supplied with pimps of the worst class. These men were promptly dealt with by the police, the authorities giving the most sympathetic assistance to the military.

As in other countries, there were graduations in the class of women employed, and the personal impression gained by the authorities was that the danger of infection was greatest from those at the top and the bottom of the social scale. Prostitutes who were registered were examined by a New Zealand gynecologist, who did the work very thoroughly, and conscientiously, and with kindness. Women who were free from disease were furnished with a ticket indicating that they were healthy. At the beginning of the war there were 800 of these women in Cairo, but as the war progressed the number grew to 1,600. The arrangement then differed in no way from the arrangements in Melbourne or Sydney except that the surveillance of the police was direct, and medical examination was insisted upon. It further had this advantage over those of Melbourne and Sydney, that the women were confined to one particular part of the city, and no one need come in contact with them unless they wanted to. Consequently for those who went to this quarter there is no excuse, since they acted deliberately.

ProphylaxisAt the same time, when all these measures were weighed in the balance – plain speaking to the men on arrival, police surveillance, medical examination, etc. – it was felt that more might be done. A number of medical officers accordingly gave instruction to their men in the means of effecting prophylaxis and of preventing infection in the event of association with these women. The medical officers acted entirely on their own responsibility. They advised the men to avoid the risk, but as they knew a certain number would not take their advice in any circumstances – in fact the men said as much – they showed them how to avoid infection if they would take the necessary trouble.

Result of ProphylaxisIn the case of our own unit, the First Australian General Hospital, trouble was taken to explain in detail the consequences of venereal diseases to the men, and to those with whom they would be associated in later life. They were asked to refrain from taking the risk, but for those who would not take the advice – and there was bound to be a percentage – the necessary directions and material were provided for preventing infection. The result was challenged by a medical officer, and an immediate examination of all the men made, when it was found that in the whole of the unit only one man was infected. In other words, the precautions taken had practically stamped the disease out of the unit, and shortly after arrival in Cairo.

Once the disease was acquired the treatment was troublesome to a degree. The men knew they were disgraced; they would probably be sent back to Australia; and in some cases, those of the finer men, the consequences were serious. Mostly, however, they developed an attitude of sullenness and indifference, a tendency to lack of discipline, and they rendered the management of camps difficult. These troubles to a large extent disappeared when a suitable hospital was established.

Soldiers' ClubsBut another and constructive side of the matter appealed forcibly to those concerned. Why not supply for the benefit of the men places of entertainment with music, refreshments, and the like, similar to and better than those which the prostitutes supplied, but minus the prostitute. In other words, why not give a healthy and reasonable alternative? After consultation with His Excellency Sir Henry MacMahon, with the G.O.C. – in-Chief, General Sir John Maxwell, and with the D.M.S. Egypt, General Ford, the Australian Red Cross Society determined to combine with the Y.M.C.A. and establish clubs for the soldiers in central positions where these requirements would be met. They accordingly established a club at the quay in Alexandria, and a magnificent open-air club in the Esbekieh Gardens, Cairo. They were both immediately successful, and have played a most important part in the further limitation of the amount of venereal disease. It is difficult to give statistical evidence, but there is no doubt that by these various means a sensible difference has been produced in the incidence of disease amongst the troops.