полная версия

полная версияThe Australian Army Medical Corps in Egypt

There is no doubt that one medical officer (who could be attached to the Pathological Laboratory in addition to the Clinical Pathologist) should devote himself entirely to sanitary work. This duty is not taken too seriously, and should be emphasised. It would really be better to rename this officer the "Prophylactic Officer," unless a better term can be found, and it should be his aim and duty, not simply to enforce cleanliness, but to actively exert himself to ward off disease.

Stress may be laid on the usefulness of a sensible chaplain, whose value depends on his own interpretation of his duties. The chaplain (Colonel Kendrew) at No. 1 General Hospital not only attended to the religious needs of men, but earned their affection and respect by managing the extensive post office and library, the canteen, and by helping with Red Cross work. It is just these badly defined functions in a base hospital which a chaplain can discharge so well.

We think also that women might be used in base hospitals as stenographers, ward maids, telephone operators, and the like. Base hospitals in the future are not likely to be housed in tents, and under rough conditions. At present, trained nurses are sent to the Stationary Hospitals. It seems a pity to waste fine young men, who could be combatants, as orderlies in a base hospital.

Masseurs are certainly badly wanted in a base hospital, and it is difficult to understand the objection to their incorporation. The difficulty was removed in Egypt by employing Egyptians.

Electricians, i. e. orderlies who in civil life are electricians, are required in every base hospital, and at Heliopolis they were invaluable for general purposes, and as aids to the radiographer. They should, however, form part of the establishment, and should number two or three.

Is it not clear that chefs, laundrymen, skilled carpenters, and other tradesmen are also required?

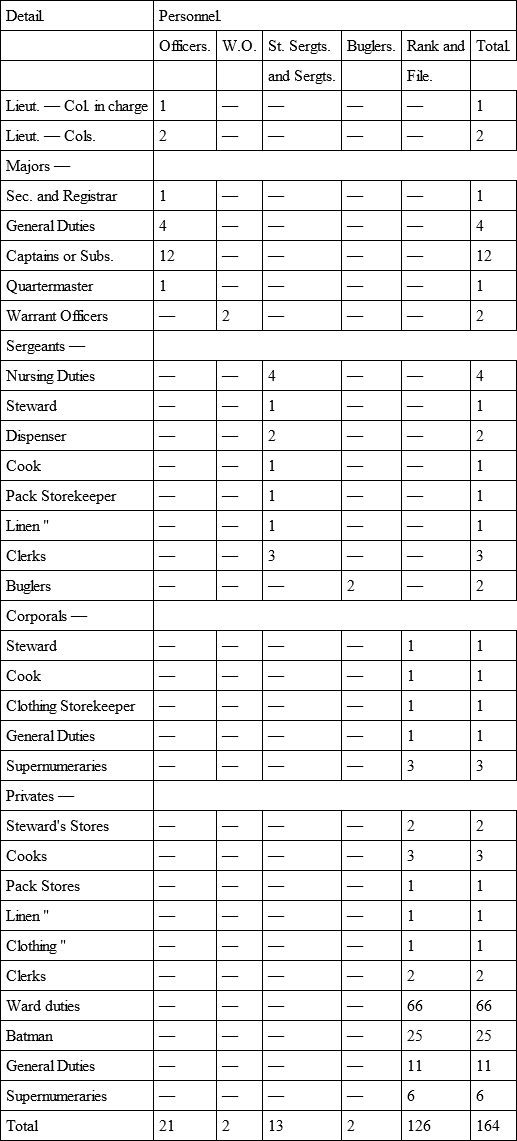

The table which follows represents the establishment of the ordinary 520-bed hospital, R.A.M.C. It has been adopted by Australia, but the Australian establishment allows for 93 nurses instead of 43. If the foregoing suggestions are adopted, as we think they should be, this table would require material alteration.

A GENERAL HOSPITAL (520 BEDS)War Establishments

With reference to the duties of N.C.O.s and men, nothing gave more trouble than the fact that men recruited in Australia were made N.C.O.s before their special qualifications were known. There is no officer in the Army whose position is so thoroughly safeguarded as the N.C.O., and nothing but the adverse decision of a court martial can effect his removal. Yet an unsuitable and even dangerous man, from the point of view of the sick, may do nothing to warrant a court martial (which no one enjoys). These appointments should be made therefore with great care. Such considerations, of course, lead to but one conclusion, viz. the necessity for sketching out these hospitals in time of peace. Scratch enlistments are too dangerous.

The "grouser" is always with us, and sometimes gives trouble. The particular Australian "grouse" was that the Australian hospitals should have been nearer the front than Cairo, and at last No. 3 Australian General Hospital was placed at Mudros.

Now we have always understood that a large base hospital cannot be placed far from a great city. A city grows in a particular place for natural reasons – water supply, lighting, transit, etc. The hospital gets the benefit of all these agencies, whereas it was necessary at Lemnos to create them. The result was somewhat disastrous as regards supplies, and might have been foreseen.

"Grousers" should stay at home, and exercise their privileges there.

The difficulties of obtaining supplies by requisition were easily surmounted at Heliopolis because of the broad policy adopted by the Officer Commanding the Australian Intermediate Base, Colonel Sellheim, C.B.

Ordnance cannot supply the varied requirements of a group of expert medical officers during a great war, and delays cause untold annoyance to active men. On the other hand, it would never do to give the staff a free hand to purchase when and how it pleased.

The institution of "local purchase orders" met the difficulty. The O.C. of the hospital sent in a requisition for something which could not be obtained from Ordnance, marking it "urgently required." The A.D.M.S. endorsed it, or, if it were an entirely new line, asked the D.M.S. to endorse it. The Ordnance officer then issued a local purchase order to the medical officer, who made the purchase. The method combined a measure of control with reasonable speed in execution.

We have no sympathy with the usual references to military red-tape. If the administration is competent, the military system is thoroughly sound from the business point of view, and from the standpoint of record difficult to improve on. It may be at times a little cumbersome, but it is much easier to fall in with it than to attempt to effect alteration during war. We never had any real difficulty with requisitions, although supplies were sometimes withheld from us on grounds of policy not disclosed at the moment.

There is no doubt that the erratic changes of staff were injurious. Some medical officers preferred the front, others the base, and an attempt was made to effect an orderly system of periodical exchange. Orders, however, were continually arriving to send so many medical officers, so many nurses, and so many orderlies, here and there, with the result that at the end of ten months the original medical staff had disappeared, many of the nurses were new, and so were most of the orderlies. Whenever there was a shortage of staff near the front, the base hospitals were depleted. These changes were inevitable in the circumstances, but they emphasised the value of the advice given by Colonel Manifold, that there cannot be too many unattached junior medical officers in a campaign.

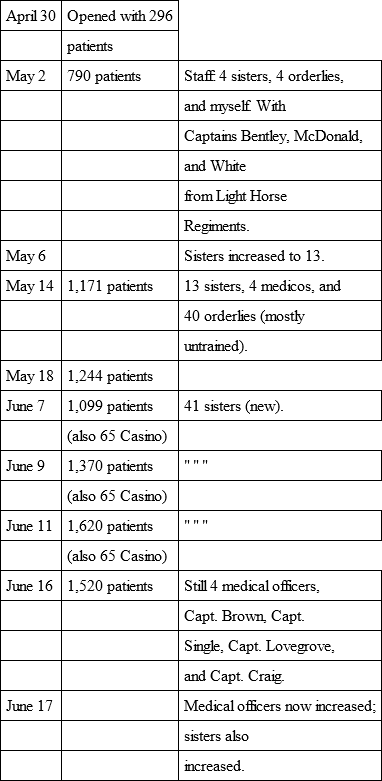

The following report from Major Brown, Officer Commanding Luna Park No. 1 Auxiliary Hospital, shows what he experienced owing to these oscillations:

First Australian General Hospital, Luna Park

With reference to orderlies, the work from May 3 has been done with 10 A.M.C. men and 30 men drawn from the patients.

On June 17, 40 reinforcement A.M.C. men were detailed for duty. Up to June 16 over 1,600 patients have been discharged. On May 23 the Operating Theatre was opened.

For the 1,600 patients we had six cooks with six natives to assist.

T. F. BROWN, Captain,Officer in Charge, Luna Park.Heliopolis,

June 17, 1915.

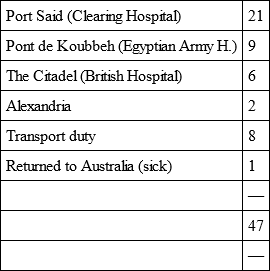

Of the 93 nurses belonging to the hospital, within a week of landing no fewer than 47 were taken away and dispatched to various parts of Egypt, viz.:

No. 1 Australian General Hospital was much inspected by keen and curious, as well as sympathetic, eyes. His Highness the Sultan, Their Excellencies Sir Henry and Lady MacMahon, the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Egypt, the General Officer Commanding Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, and many other distinguished people honoured the hospital by an inspection.

The following letters were written by three distinguished visitors. Two Corps Orders are also attached.

"Shepheard's Hotel, Cairo,"May 20, 1915."Dear Colonel Ramsay Smith,

"Allow me to congratulate you upon the admirable medical arrangements at Heliopolis, and upon the excellent hospital you have established there. One is at first disposed to say, 'How well the building adapts itself to a hospital!' until the true fact becomes revealed of the genius displayed in converting a decidedly refractory building into a place for the sick. You and your staff have done wonders and have once more shown that in the land of Egypt 'it is possible to make bricks without straw.'

"Australia may well be proud of the part she has played in this war, and I can pay no higher compliment than by saying that the medical arrangements of the Australian Army are as splendid as are the fighting qualities of its men.

"Above all I was impressed with the energy and enthusiasm with which the work at Heliopolis is being carried on, with the ingenuity and resource displayed at every turn, and with the thoroughness that was manifest in every department of the vast hospital.

"The generosity with which Australia has provided motor ambulances for the whole country and Red Cross stores for every one, British or French, who has been in want of same is beyond all words.

"I only hope that the people of Australia will come to know of the splendid manner in which their wounded have been cared for, and of the noble and generous work which the great colony has done under the banner of the Red Cross.

"Yours sincerely,"(Signed) Frederick Treves.""Turf Club, Cairo,"June 21, 1915."Dear Colonel Ramsay Smith,

"I am just off to the Dardanelles, and then back to Cairo, but I felt that I must write and thank you for your kindness in sending me those excellent and interesting photographs, which I shall treasure, and the memory of the interesting day I spent with you at your wonderful hospital. I also thank you for your report and for the copy of Sir F. Treves's letter.

"You must feel proud of your work at Heliopolis, on which I heartily congratulate you. It is a monument of skill in administration and the surmounting of what would at first appear to be insurmountable difficulties.

"Hoping soon to see you again,"Yours very sincerely,"(Signed) A. W. Mayo-Robson.""St. Mark's Buildings, Alexandria,"June 5, 1915."Dear Major Barrett,

"I have been away at the front or I should have written to you sooner to thank you for the interesting visit which you enabled Sir Frederick Treves and myself to pay to your hospital and stores. I enclose an extract of a report which I made on May 25 to the Hon. Arthur Stanley, Chairman of the British Red Cross Society and Order of St. John in London.

"You may have noticed a minute published in the press with the approval of the G.O.C., Sir John Maxwell, in which it was laid down that all Red Cross work, except the Australian Red Cross work, should be under the control of the British Red Cross and Order of St. John. I hope you will not think that in drafting this minute in this way I wished to convey that we were not working in perfect harmony with your Red Cross, but I feel that we could hardly suggest to you that you should be in any way under our control. At the same time, I hope that when you either come here, or when I come back to Cairo, that we may have an opportunity of conferring together so that we may so co-ordinate as far as possible our mutual work.

"May I add that I went to the Dardanelles in a transport with over a thousand of your brave soldiers, many of whom were returning to the Peninsula after having already been wounded. It is impossible to speak too highly of their gallantry, and of the splendid spirit they displayed. I need not tell you that I heard of their fighting qualities at the front, since their heroic deeds in this campaign have already become a matter of history.

"Yours sincerely,"(Signed) Courtauld Thomson,"Chief Commissioner for British RedCross and Order of St. John, Malta,Egypt, and Near East Commission."[Copy]Extract from a Report from Lieut. – Colonel Sir Courtauld Thomson, Chief Commissioner of the British Red Cross and Order of St. John, to the Hon. Arthur Stanley, dated May 25, 1915.

"A striking feature in Cairo is the remarkable work which is being done by the Australian Red Cross. They have not only two exceptionally large hospitals and the large convalescent home, but they supply the motor transport for the wounded for the whole of Egypt. They have also very large Red Cross stores which they have brought with them. With these articles they have been more than generous, and I am informed that they have given away to the hospitals for our own troops something like 75 per cent. of whatever they had."

Extract from Corps Orders, March 28, 1915

"Appreciation.– The D.M.S. Egypt, who visited the Hospital yesterday afternoon, has requested the Officer Commanding to convey to the officers, nurses, N.C.O.s, and men in the Hospital his appreciation of the work done and the thorough character of the organisation."

Extract from Corps Orders, May 1, 1915

"Appreciation.– The D.M.S. Egypt, Surgeon-General Ford, witnessed the detraining of the invalids who arrived here Wednesday evening. He asked Major Barrett to convey to the Officer Commanding his great appreciation of the excellence of the arrangements and the efficient and quiet manner in which the work was done.

"He congratulates officers and men on the splendid work they are doing and requests that it shall be communicated to them in Corps Orders."

Looking back, does it not seem essential that these hospitals should have been formed, at all events in outline, in time of peace? That their commanding officers and essential staff should have been marked out beforehand, so that on the declaration of war the gaps could have been filled in from the reserve without difficulty? Satisfactory appointments are much less likely to be made in the turmoil which follows the declaration of war than in the atmosphere of deliberate calm which prevails in time of peace. Had such an arrangement prevailed, the First Australian General Hospital would certainly never have been recruited from three States distant from one another hundreds of miles.

Finally, Australian hospitals in time of war should either be regarded as responsible solely to the Australian military authorities and Government, or handed over without reserve to the R.A.M.C., and placed entirely under the control of the British authorities. Where two different authorities exist, as in the case of the First General Hospital, a large amount of trouble and delay is almost certain to ensue. The adoption of the latter course is in our judgment absolutely essential if efficiency is to be secured.

As is invariably the case, weaknesses in any system are only revealed by costly experience. But while in the Australian Medical Service the experience need not have been so costly, we can at least profit by what has occurred, and frame a stronger and a better policy for the future.

On the whole, the record of work done in most trying circumstances is, we think, satisfactory. It is true that the universal democratic fault was evidenced in the lack of preparation for conditions which were fairly obvious. Nevertheless the adaptability and growth of the hospitals in time of great emergency were achievements of the highest order.

Yet it would be unwise to leave the subject with the usual Anglo-Saxon expression of satisfaction that the crisis was passed. The history reviewed has too deep a significance. It must be regarded not merely as an individual incident, but as an indication of the inefficiency evidenced by too many departments of the Empire.

The causes which found the medical services unprepared, which forced them to expand to the breaking-point, and which led to the criticism of the hospital authorities, are not departmental or sectional – they are national. If attacks on individuals are permitted, initiative will be stifled; if on the other hand we are content to follow the time-worn policy of "muddling through," the virile people who skirt the border lines of our Empire will sooner or later bid us make way for stronger men.

Our policy for the future must be one of scientific organisation and calculated preparation in every department. We must not only appoint capable administrators, but also trust them. We can again, if we like, obtain that temporary mental tranquillity which comes to a democracy – and to an ostrich – which does not or will not see the calamity which threatens it, but temporary beatitude will be purchased at the price of an Empire. Never was it more certainly true that the price of liberty is eternal vigilance.

CHAPTER XI

POSTSCRIPTCLOSURE OF AUSTRALIAN HOSPITALS – THE FLY CAMPAIGN – VENEREAL DISEASES – Y.M.C.A. AND RED CROSS – MULTIPLICITY OF FUNDS – PROPHYLAXIS – CONDITION OF RECRUITS ON ARRIVAL – HOSPITAL ORGANISATION – THE HELP GIVEN BY ANGLO-EGYPTIANS.

One of us (J. W. B.) was invalided to England in the middle of November 1915, and returned to Egypt at the end of March 1916.

He resigned his commission in the Australian Army Medical Corps on February 28, and was appointed temporary Lt. – Col. in the R.A.M.C. on February 29. On his return to Egypt he was appointed Consulting Aurist to the Forces in Egypt, and was a member of the Council of the British Red Cross Society and of the Y.M.C.A. He consequently had an opportunity of witnessing the termination of many of the arrangements for which he had been in part originally responsible, and desires to make brief reference to them.

No. 1 Australian General Hospital with its many off-shoots, including the four auxiliary hospitals and the venereal disease hospital, was located in Egypt for periods of twelve to eighteen months. No. 2 Australian General Hospital was in Egypt about fourteen months. Yet it was stated that each and every one of these hospitals when established were to be temporarily located in Egypt for a few weeks. Luna Park, i. e. No. 1 Auxiliary Hospital, was in existence approximately sixteen months. An enormous number of sick and wounded, said to be 18,000, was passed through it with an infinitesimal death-rate, viz. four or five persons. Since the end of 1915, the No. 3 Australian General Hospital was moved from Mudros to the Barracks at Abbassia, Cairo. The expenditure necessary to fit the barracks for the reception of No. 3 Australian General Hospital and the time taken are very interesting, since they show how utterly impossible any such arrangement would have been during the inrush of wounded in 1915. Stress is laid on the value of auxiliary hospitals as the only practicable means of surmounting difficulties at that time, in the report of the Committee of Inquiry into the Administration of the Australian Branch British Red Cross in Egypt.

Looking back at the practical conclusion of the work of the Australian Army Medical Corps in Egypt, it is quite evident that the policy originally adopted was the only one possible in the circumstances, and the results have fully justified it.

The Fly CampaignVery active steps were taken during 1916 in the direction of a campaign for the destruction of flies. The only addition that need be made to previous remarks is reference to the ingenious fly traps which have been devised. A large one was designed by Lt. – Col. Andrew Balfour, C.M.G., and is described in the journal of the Army Medical Corps of July 1916. A modified form of this trap, furnished by the British Red Cross in Egypt, costs about 16s., and was most effective. These traps have been known to catch as many as 20,000 flies a day.

The smaller trap, which can be used indoors, and is made of zinc gauze, was made in large quantities by the British Red Cross Society in Alexandria, and distributed throughout Egypt.

Another kind of trap, a Japanese invention, with clockwork mechanism, manufactured by Owari Tokei, Kabushiki, Kwaisha, Japan, has also been very successful. As many as 3,000 flies have been captured in one instance in an hour. It has a considerable advantage over the other traps in that its mechanism interests everyone.

Like all fly traps, however, the utility of these devices depends upon placing them in the hands of men whose business it is to see that they are properly baited and cared for, and on some ingenuity with regard to the baits. For the larger traps placed out-of-doors the best baits were found to be fishes' heads or the entrails of fowls, whilst the best bait for the smaller indoor trap was a mixture of beer or whisky and sugar.

It is, of course, quite evident that the destruction of flies by traps is not logically sound, since the proper method of control of the fly pest is by the destruction of all refuse; but as that is impracticable in Egypt, the traps were of great assistance.

In 1916 the fly pest as usual became marked during two periods in the year; viz. at the beginning and the end of summer. At the height of summer the dryness and desiccation evidently prevent the breeding of flies, a fact to be borne in mind in Australia.

The returns given in the House of Commons respecting the Gallipoli Campaign place the casualties at 116,000, and the cases invalided at 96,000. As a very large number of the cases of the sick were due to intestinal infections, some idea of the damage which may be caused by flies can be imagined.

The discovery of bilharzia eggs and the organisms of dysentery and diarrhœa in the fæces of flies made it clear that the fly plays an even larger part in disseminating disease than has hitherto been understood. It really would appear that if the flies were destroyed infective diseases would fall to small proportions.

The Venereal-Disease ProblemThe venereal-disease problem in the early part of 1916 gave very great concern, and active measures were taken to deal with it. In spite of all the ameliorating influences the problem reached its most serious phase in March and April 1916, as questions put in the House of Commons show (vide Lancet, April 8, 1916). I think I express the conviction of certainly 90 per cent. of medical men in stating that nothing but education and educated prophylaxis will ever enable us to get rid of this source of destruction.

Y.M.C.A. and Red CrossThe Soldiers' Club in the Ezbekieh Garden grew in favour and was extended in area and staff. In the autumn of 1915 some ladies became available, and did splendid service in the superintendence of the catering for the men in the Club, and by their presence there did much to help.

A more extended experience of the work of the Y.M.C.A. and of the Red Cross has given much cause for thought. The Y.M.C.A. organisation appears to me to be excellent, since it is the organisation which caters for the social welfare of the soldier, wherever he may be, whether in camp or at the base; and the work is conducted by men whose business it is to understand him and see that all reasonable wants are gratified. In Egypt as I write (July 1916) there are no fewer than forty-seven Y.M.C.A. huts and centres, and Y.M.C.A. officers in the desert, in the oases, and elsewhere, doing their very best to make the soldiers comfortable. In other words, the business of the Y.M.C.A. is to provide comfort by personal service over and above military necessaries for the men who are well.

The Red Cross Society, on the other hand, attends to the wants of the sick and wounded, and its functions have already been discussed. They may, however, be supplemented by the following definition of the work of the Red Cross which was furnished by the High Commissioner for Egypt, Sir Henry MacMahon:

"Government supplies all the necessities for the care, treatment, and transport of the sick and wounded, while the Red Cross supplements these necessities by everything that can in any way go to the comfort and well-being of the sick and wounded soldiers. The distinction between necessities and comforts is sometimes so indefinite that the Red Cross, wherever possible, endeavours to have both ready to hand for use when needed."

And later:

"A word must be said here about the work of the Red Cross Stores. The object of the Red Cross has never been to supply in any large quantities the goods which the War Office sends to the wounded, but it does its best to provide the troops with such things as the War Office does not supply at all or cannot supply at a given time. A State Department, bound as it rightly is by hard-and-fast rules, cannot work as quickly as a private body with more elastic regulations; moreover, the supplies of any department may change at times, hence it happens that the British Red Cross occasionally supply certain things more than the War Office can, or it may supplement the War Office supplies, and it does so until the War Office steps in again. Further, the Red Cross supplies many things or small luxuries which the authorities cannot possibly supply, and these are just the things which are most appreciated by the sick and wounded."