полная версия

полная версияThe Australian Army Medical Corps in Egypt

In conclusion it should be pointed out that during the whole period under review all necessary services were provided by the military authorities and the Red Cross was administered on military principles. Consequently there were no large expenses, no one received any money in payment for services, and the storage of goods was free.

If the Red Cross is to be administered on non-military lines many charges must be properly made and met, but the efficiency of the system instituted and now set aside must be judged largely from the standpoint of economic administration.

James W. Barrett,Lieut. – Colonel.(In this volume the original report forwarded to Melbourne has been expanded and amplified.)

Appendixes1. Directions for the Conduct of the Red Cross DepotDepot – conduct of.

1. The Depot is placed under the charge of a Medical Officer who will have at his disposal nurses and orderlies in such numbers as the work from time to time may necessitate.

Storage of goods.

2. All goods consigned to the Red Cross Depot shall be placed in store at once and rendered secure under lock and key at other than business hours.

Receipt Book.

3. All goods received will be entered in the Goods Receipt Book.

Requisitions – how dealt with

4. On receipt of requisitions signed by the Officer Commanding any unit, and countersigned by the Officer Commanding First Australian General Hospital, goods will be issued, and if necessary transport provided. Two clear lists shall be prepared on forms provided for the purpose, one to be receipted and returned to Red Cross Depot by the consignee and duplicate to be filed in Office.

Stock-taking.

5. A Stock Book is to be kept showing the nature and quantity of material received, and the quantity distributed, so that at any time the stock remaining can be ascertained. This book to be checked once a month by stock-taking of the contents of the store and certified to by the M.O. in charge.

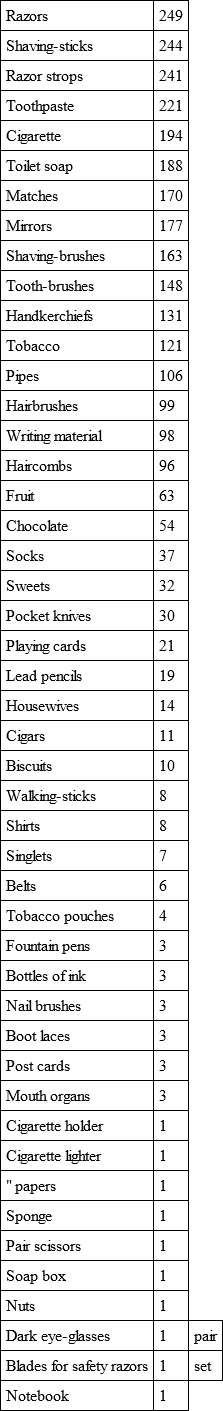

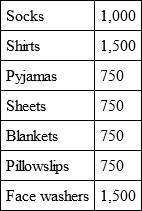

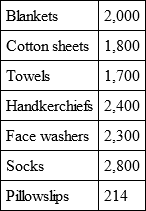

2. Result of Vote at No. 1 Auxiliary Convalescent DepotThe following items represent the wishes of 840 patients at Luna Park on July 29, 1915, ascertained by the O.C., Major Brown.

Four hundred and forty papers were received, a great number of patients failing to vote.

The patients were asked to make a list of twenty to thirty articles that would add to their comfort during their stay in hospital, and which could be supplied by a small fund at his disposal.

The average items on collected lists were 8.

Some critics have objected to the Red Cross assisting Soldiers' Clubs. The following lines are commended to their notice. But for the Australian Branch British Red Cross there would have been no such Soldiers' Clubs as those provided at Esbekieh and Alexandria.

'Twas a dangerous cliff, as they freely confessed,Though to walk near its crest was so pleasant;But over its terrible edge there had slippedA duke, and full many a peasant.So the people said something would have to be done,But their projects did not at all tally:Some said, "Put a fence round the edge of the cliff";Some, "an ambulance down in the valley."But the cry for the ambulance carried the day,For it spread through the neighbouring city,A fence may be useful or not, it is true,But each heart became brimful of pityFor those who had slipped over that dangerous cliff;And the dwellers in highway and alleyGave pounds or gave pence, not to put up a fence,But an ambulance down in the valley."For the cliff is all right if you're careful," they said,"And if folks even slip and are dropping,It isn't the slipping that hurts them so muchAs the shock down below when they're stopping."So day after day, as those mishaps occurred,Quick forth would these rescuers sallyTo pick up the victims who fell off the cliff,With the ambulance down in the valley.Then an old sage remarked, "It's a marvel to meThat people give far more attentionTo repairing results than to stopping the causeWhen they'd much better aim at prevention.Let us stop at its source all this mischief," cried he,"Come, neighbours and friends, let us rally!If the cliff we will fence we might almost dispenseWith the ambulance down in the valley.""Oh, he's a fanatic," the others rejoined."Dispense with the ambulance? Never!He'd dispense with all charities, too, if he could!No, no! We'll support them for ever!Aren't we picking folks up just as fast as they fall?And shall this man dictate to us? Shall he?Why should people of sense stop to put up a fenceWhile their ambulance works in the valley?"But a sensible few, who are practical too,Will not bear with such nonsense much longer;They believe that prevention is better than cure,And their party will soon be the stronger.Encourage them, then, with your purse, voice, and pen,And (while other philanthropists dally)They will scorn all pretence, and put a stout fenceOn the cliff that hangs over the valley.Better guide well the young than reclaim them when old,For the voice of true wisdom is calling:"To rescue the fallen is good, but 'tis bestTo prevent other people from falling.Better close up the course of temptation and crimeThan deliver from dungeon or galley;Better put a strong fence round the top of the cliff,Than an ambulance down in the valley."Joseph Malines.The Red Cross Policy: Wanted, a DefinitionBefore leaving consideration of the details of the Red Cross question, attention should be directed to the numerous changes in the policy adopted by the British Red Cross Society, Australian Branch. No less than three different types of administration were rapidly adopted. It was first placed in the hands of Surgeon-General Williams and the High Commissioner for Australia, in London; then it was placed under a committee in Egypt formed by the High Commissioner for Egypt, Sir Henry MacMahon, and six weeks later two Commissioners were appointed to take the work over. Nothing more clearly illustrates the state of mental instability in which a first experience of war had thrown the population of Australia. The policy which was adopted by Surgeon-General Williams in connection with the Red Cross administration is that which we believe to be sound.

When acting as A.D.M.S. to the Australian Force in Egypt it became my duty (Lieut. – Col. Barrett) to sanction or modify the requisitions of medical stores for the various hospitals and units, and the instructions conveyed to me were that I could sanction any requisition provided that it was reasonable. If, however, it represented a new departure it must be authorised by the D.M.S. Egypt. This meant practically that everything could be obtained from Ordnance, and many of the Red Cross supplies became superfluous. That is to say, any necessary goods in the Red Cross store were utilised, but if they had not been there the Government would have purchased them. In fact, it reduced the field in which the Red Cross could operate to comparatively small proportions. There is no doubt that, had it become necessary, I should have authorised the erection of shelter sheds and recreation huts in the various hospitals as a medical necessity. There was one advantage, and one advantage alone, in effecting these changes with the aid of the Red Cross. The action if sanctioned by superior officers could not be challenged by any one else at the time, and could be effected with extraordinary speed.

I took the view that it was the business of the Officer Commanding the hospital, with the aid of the matron, sisters, and medical officers, to let me know what was thought necessary, and unless the requirement was outrageous it was immediately supplied. As a matter of fact no single request for money or goods was ever refused or seriously modified. Owing to pressure of public criticism another policy began to make its appearance. It was asserted that it was the duty of the Red Cross officer to visit the various hospitals to find out what the patients ought to receive. It will be seen that such a policy removed from the O.C.s of the hospitals, or any one to whom they may have delegated their powers, the responsibility for determining what patients should receive. Such a policy sooner or later must result in the creation of an army of people who are worrying to find out what they can do instead of being properly instructed by those responsible for the welfare of the patients.

It further tended to place in the hands of irresponsible people some control over the medical management of hospital cases. If lay visitors can enter a hospital and provide food for patients, they may next wish to provide drugs, etc. It seemed that the policy laid down in the first instance was sound, useful, and healthy.

When the Commissioners took office they made a number of changes in detail. They shifted the position of the store; they printed different forms of requisition, and they took the goods out of the quartermaster's store and placed them in a store in the hospital, presided over by a volunteer. The goods were then obtained by requisition from the sisters and the matron. But as the President of the Red Cross Inquiry Court pointed out, with one trifling exception the method was not really altered. The control had simply ceased to be military, and had become civil. Consequently a large staff of capable people were withdrawn from their ordinary occupations in Australia, and devoted themselves to an administration which had been hitherto effected entirely by the soldiers. We do not think that the change was right or desirable. It resulted in the creation of another body, not responsible directly to the military authorities, to do what is after all subsidiary work. The inevitable tendency will be for the Red Cross to take on function after function which should be undertaken by military authorities. The Red Cross is already supplying many articles which should be, and can be, supplied by Ordnance. For there is nothing that the Red Cross can supply that Ordnance cannot still more easily supply. It is quite true that the British Red Cross is managed on civil lines, and the British Red Cross supplies goods and does not supply money. But with a full knowledge of both systems we are strongly of opinion that the military method of management is in every respect preferable.

During the Red Cross Inquiry recently finished, to which allusion will be made elsewhere, day after day was necessarily spent by the Court in endeavouring to decide what Red Cross should supply and what Ordnance should supply. What does it matter so long as the patient receives the articles? It does not concern him where they come from, and if the whole is under military control there is no need for this sharp and artificial line of demarcation. We are of opinion that in general the functions of the Red Cross should be to supply those additional comforts and accessories which make sick life more tolerable, to supply any goods which may be donated, and to make helpful donations of money in the way already indicated.

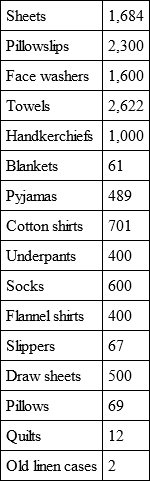

The presence in the store at Heliopolis of large quantities of goods – sheets, blankets, pillows, and the like – which could have been supplied by Ordnance, enabled us to rapidly tide over a great emergency. There is no doubt that the possession of money and goods by the Red Cross will prove of vast service in every campaign by reason of its emergency value. In fact the rapid expansion of No. 1 General Hospital during the crisis of May and June would not have proceeded with such smooth expedition had it not been for the large quantities of Red Cross stores which lay to hand and were instantly passed into the Quartermaster's department. If, however, the supply had been under lay control, we can quite imagine circumstances in which argument, requisitions, forms, etc., might have seriously delayed operations.

Whilst on this subject reference must be made to the help afforded to the hospitals by Red Cross workers. Two schools of thought existed. Some Commanding Officers preferred to have no helpers, because of the trouble some of them gave. Others passed to the other extreme. Our own experience was that the workers organised by Mrs. Elgood were most helpful for the functions they undertook, with one or two exceptions, but those exceptional people gave a certain amount of trouble. They came not to help, but to criticise, and they carried their criticisms not to the Commanding Officer, but to the Australian public, and so caused trouble.

We are convinced that the Japanese method of organising the Red Cross is sound. It is organised and disciplined in time of peace, and when war is declared it becomes part of the army medical reserve and is mobilised for service. Every one is under military control, and consequently these crudities are avoided. If we were to repeat our experience we should have welcomed the visitors, but insisted that they should be under some measure of discipline, and that a serious breach of regulations should be followed by their withdrawal. In some instances visitors wrote to the Commander-in-Chief, and complained of the food the patients were getting. The Commander-in-Chief sent the letters on to us, and we then brought the visitor in contact with the Commanding Officer of the hospital, and the complaint was investigated. How much more direct and simple it would have been if the visitor who saw something he believed to be wrong had immediately asked for the Officer Commanding! But the "secret and confidential" candid friend is apt to become somewhat of a pest.

There is another and more serious aspect of the matter. The medical officer is alone competent to judge what food should be issued to patients. Visitors who criticise the diet of the patient are assuming a function which they are obviously unable to discharge. Diet sheets are provided for each ward, and on these is entered the number of different diets prescribed by the medical officer. These diet sheets should be the only and the final authority of what should be issued to the patient in the way of eatables. As it happened, ladies sometimes brought into the different wards of the hospital foods which constituted an added danger to the patient. On one occasion green melons were issued to a large number of sick men by kind-hearted visitors. The men became so ill that the medical officer confiscated the melons, made inquiries, and only then ascertained the source of supply. A strong-looking soldier on a milk diet might evoke the sympathies of a lady visitor, who lodged a complaint regarding the supply of food, but the nature of his disease and the method of treatment adopted by his medical officer are surely the principal consideration. As everything conceivable in the nature of food and drink can be supplied through these diet sheets, the obvious course is to pass all Red Cross foodstuffs directly into the Quartermaster's department to be distributed in the ordinary, and the only safe, channel. This was the practice followed at Heliopolis.

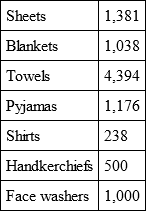

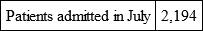

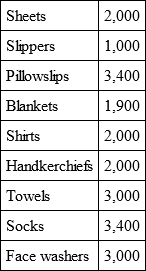

The following articles were supplied in this way at the time of expansion, and show what assistance a properly controlled Red Cross system can render.

QUARTERMASTER'S REPORT BY LIEUTENANT P. E. DEANEAssistance rendered the First Australian

General Hospital by Red Cross in Hospital

Expansion

AprilSkating Rink opened.

Abbassia Venereal Diseases Hospital opened.

Casino Infectious " " "

The following were obtained immediately on requisition on Red Cross:

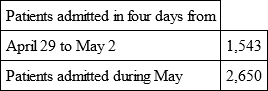

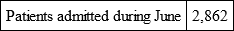

Great rush of patients – Luna Park expanded, Palace Hotel expanded.

Rush of wounded continues. Atelier occupied, Sporting Club commenced.

Special hospital organised hurriedly by the department on June 17. Ras el Tin Convalescent Home, Alexandria.

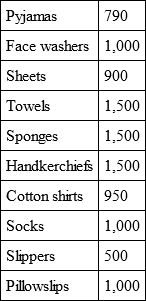

Red Cross Supplies

Wounded still pour in. Sporting Club increased by addition of tennis court wards, Atelier and Luna Park accommodation increased.

Choubra Infectious Hospital hurriedly established and equipped by the department; 400-bed tent hospital added to Sporting Club.

Red Cross Supplies

CHAPTER X

SUGGESTED REFORMS – DEFECTS WHICH BECAME OBVIOUS IN WAR-TIME – RECOMMENDATIONS TO PROMOTE EFFICIENCY – DANGERS TO BE AVOIDED – CONCLUSION.

CHAPTER XThe experience gained in connection with the establishment and extension of the First Australian General Hospital suggests modifications which should immensely increase efficiency. A base hospital modelled on the R.A.M.C. pattern may work exceedingly well in times of peace, or when staffed by R.A.M.C. or I.M.S. officers who have devoted their whole lives to the work. But base hospitals constructed during a great war, and staffed almost entirely with civilian elements the majority of whom are untrained in administration of any kind, do not work in all cases with the necessary degree of smoothness. It certainly does appear that changes in the base hospital establishment might be introduced with advantage.

In the first place there arises the question whether it is necessary for the Commanding Officer to be a medical practitioner, or whether, as in the case of the convalescent hospitals, he might be a combatant officer, or at all events a non-medical officer. The general consensus of opinion is that he should be a medical officer, though there is a great deal to be said on the other side. Almost the whole of his work is administrative, though he necessarily must have a good knowledge of clinical methods. But unless such an officer be selected not simply with regard to seniority, but with regard to experience in administrative methods, and unless he be tactful and watchful, troubles are very likely to ensue. His task is beset with difficulties if he possesses character and insists on efficiency. Whatever doubt there may be, however, about the Commanding Officer, there need be none about many of the other positions. A noteworthy feature of the First Australian General Hospital was the continual complaint from the medical officers that they had not come away to do administrative work. This distaste for administrative work was a constant source of trouble.

The Registrar, as the principal executive officer of the hospital, whose business it is to carry out the decisions of the Commanding Officer, is at present invariably a medical officer. The greater part of his work does not need medical knowledge, and the difficulty might be obviated by the adoption of one of two methods. Either the Registrar might be an educated business man or he might have such a one as his immediate understudy. In the latter event a very small portion of his day would be taken up with the duties of the Registrar's office.

Similarly the orderly officer, whose business it is to deal with details concerning the rank and file, is usually a medical officer, and in some hospitals it is the practice to change this officer from day to day. At No. 1 General Hospital, however, his functions were so important that one medical officer was permanently told off to do this work. There is no doubt that the orderly officer need not be a medical officer, and might well be an invalided combatant officer, transferred to the army medical service.

Owing to modern developments another officer has made his appearance who is not provided for in any establishment – that is, the transport officer. Motor transport has become so large a portion of the work of the base hospital that a special officer is requisite for the purpose. There is no reason whatever why such an officer should be a medical man.

If these changes were made it would result in releasing at least three officers for clinical purposes.

The amount of clerical work that was necessitated by the returns furnished to the War Office, the Australian Government, Headquarters Egypt, and other departments was so great that a large staff of very competent clerks was required. The future establishment should certainly include not only a number of trained stenographers, but some one versed in statistical work. The lessons to be learned are so numerous and so important that something of the kind should be done. Furthermore, in the Quartermaster's department there was a demand not only for stenographers, but for men who had been accustomed to the methodical ways of a large warehouse.

Were all these changes made there is no doubt that the efficiency of the administration would be increased and the burden of the work lightened.

As regards clinical work other desirable changes might be made. Senior men who have been in full practice, and who come to a base hospital as physicians or surgeons with the rank of lieutenant-colonel, are apt to be entrusted with the detailed administration of medical or surgical wards. They are often unfitted by training for such administration and are frequently disinclined to undertake the work. It would be far better to leave the actual detailed administration of the wards in the hands of a comparatively junior man with the rank of major, and to retain these senior officers as consultants only. Consultants of course possess great powers, since their authority as regards the clinical work itself is absolute. They can do as much or as little as they like, but they are in complete control and are absolutely responsible for the treatment of the cases. Our own feeling is that in such a position they would be far more comfortable and would be more efficient.

On the subject of specialists there is much to be said. It is almost incredible that a base hospital should have been formed without being provided with an ophthalmic and aural specialist. The change has been made since war began, but it seems inconceivable that any one should have contemplated the efficient handling of wounds and diseases without such aid. At the First General Hospital the ophthalmic and aural department was the largest and most heavily worked department in the hospital, partly owing to the fact that one of us had been appointed Consulting Oculist to the Forces in Egypt, and that much of the work consequently centred at Heliopolis.

Similarly the failure of the Australian Government to provide dentists in the first instance is difficult to understand. The day has gone by when it is possible to exclude from the force a man who possesses dentures or defective teeth, and it is practically impossible to complete the work for the recruits before they leave. So it became necessary at No. 1 General Hospital to borrow two dentists from the New Zealand Government, to fit them out with Red Cross money and goods, and in this way to meet informally the difficulty. Subsequently the Australian Government appointed a corps of dentists, and the problem was to some extent solved, though even now the demand far exceeds the supply. There is no doubt that dentists are wanted not only at the base hospitals, but also near the firing line, as the dispatch of a man from the firing line to the base hospital to obtain dental treatment represents a waste of time and money.

It is further desirable to attach one or more anæsthetists to every hospital.

It must, however, be said that the constant changes of staff which took place at No. 1 Hospital owing to the various exigencies of the military situation rendered it extremely difficult to keep a physician or surgeon in any fixed position for any length of time. Consequently a certain amount of pliability and adaptability was absolutely necessary. At the same time, if the organisation were sketched in the manner indicated, the problem would have been more simple, and good results easier to obtain.