полная версия

полная версияThe Australian Army Medical Corps in Egypt

James W. Barrett, Percival E. Deane

The Australian Army Medical Corps in Egypt / An Illustrated and Detailed Account of the Early Organisation and Work of the Australian Medical Units in Egypt in 1914-1915

INTRODUCTION

The experience of the Australian Army Medical Service, since the outbreak of war, is probably unique in history. The hospitals sent out by the Australian Government were suddenly transferred from a position of anticipated idleness to a scene of intense activity, were expanded in capacity to an unprecedented extent, and probably saved the position of the entire medical service in Egypt.

The disasters following the landing at Gallipoli are now well known, and the following pages will show how well the A.A.M.C. responded to the call then made upon it.

When the facts are fully known, its achievements will be regarded as amongst the most effective and successful on the part of the Commonwealth forces.

In the following pages we have set out the problems which faced the A.A.M.C. in Egypt, regarding both Red Cross and hospital management, the necessities which forced one 520-bed hospital to expand to a capacity of approximately 10,500 beds, and the manner in which the work was done.

The experience gained during this critical period enables us to indicate a policy the adoption of which will enable similar undertakings in future to be developed with less difficulty.

We desire to acknowledge gratefully the permission to publish documents granted by General Sir William Birdwood and Dr. Ruffer of Alexandria, and also much valuable help given by Mr. Howard D'Egville.

The beautiful photographs which are reproduced were mostly taken by Private Frank Tate, to whom our best thanks are due.

In any reference to the work of the Australian Army Medical Corps in Egypt it must never be forgotten that the expansion of No. 1 Australian General Hospital was effected under the personal direction of the officer commanding, Lieut. – Colonel Ramsay Smith, who was responsible for a development probably unequalled in the history of medicine.

The story told is the outcome of our personal experience and consequently relates largely to No. 1 Australian General Hospital, with which we were both connected.

CHAPTER I

THE AUSTRALIAN ARMY MEDICAL CORPS AT THE OUTBREAK OF WAR – THE CALL FOR HOSPITALS – APPEAL TO THE MEDICAL PROFESSION AND THE RESPONSE – RAISING THE UNITS.

CHAPTER IPrior to the outbreak of war in August 1914, the Australian Army Medical Corps consisted of one whole-time medical officer, the Director-General of Medical Services, Surgeon-General Williams, C.B., a part-time principal medical officer in each of the six States (New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia, and Tasmania), and a number of regimental officers. With the exception of the Director-General, all the medical officers were engaged in civil practice, which absorbed the greater portion of their energy.

The system of compulsory military training which came into operation in 1911 was creating a new medical service, by the appointment of Area Medical Officers, whose functions were to render the necessary medical services in given areas, apart from camp work. These also were mostly men in civil practice, to whom the military service was a supplementary means of livelihood.

Camps were formed at periodical intervals for the training of the troops, the duration of the camps rarely exceeding a week. At these camps a certain number of regimental medical officers were in attendance, and were exercised in ambulance and field-dressing work.

In common with the members of other portions of the British Empire, few medical practitioners in Australia had regarded the prospect of war seriously, and in consequence the most active and influential members of the profession, with some notable exceptions, held aloof from army medical service.

In 1907, however, owing to the representations of Surgeon-General Williams, and to the obvious risk with which the Empire was threatened, senior members of the profession volunteered and joined the Army Medical Reserve, so that they would be available for service in time of war. The surgeons and physicians to the principal hospitals received the rank of Major in the reserve, and the assistant surgeons and assistant physicians the rank of Captain. Some attempt was made to give these officers instruction by the P.M.O's, but the response was not enthusiastic, and little came of it.

At the same time there were a number of medical officers in the Australian Army Medical Corps who possessed valuable experience of war, notably the Director-General, whose capacity for organisation evidenced in South Africa and elsewhere made for him a lasting reputation. The Principal Medical Officer for Victoria, Colonel Charles Ryan, had served with distinction in the war with Serbia in 1876, and in the war between Russia and Turkey in 1877. A fair number of the regimental officers had seen service in South Africa. The bulk of the medical practitioners concerned, however, had not only no knowledge of military duty, but certainly no conception whatever of military organisation and discipline; and what was still more serious, no real and adequate realisation of the extraordinary part that can be played in war by an efficient medical service by prophylaxis.

Such, then, was the position when war was declared.

The response from the people throughout Australia was, as Australians expected, practically unanimous. They determined to throw in their lot with Great Britain and do everything that was possible to aid. This determination found immediate expression in the decision of the Government of Mr. Joseph Cook, endorsed later by the Government of Mr. Fisher, to raise and equip a division of 18,000 men and send it to the front as fast as possible. The system of compulsory military service entails no obligation on the trainee to leave Australia, and in any event, the system having been introduced so late as 1911, the trainees were not available. The expedition consequently became a volunteer expedition from the outset. Volunteers were rapidly forthcoming, camps were established in the various States and training was actively begun.

Of the difficulty and delays consequent on the raising of such a force – of men mostly civilians, of all classes of society, without clothing, or with insufficient clothing and equipment of all kinds – little need be said. The difficulties were slowly overcome, and the force gradually became somewhat efficient. As both officers and men were learning their business together, the difficulties may well be imagined. In fairness, however, it should be said that from the physical and from the mental point of view the material was probably the finest that could be obtained.

We are, however, only concerned here with the medical aspect of the movement. The medical establishment was modelled on that of Great Britain, and consisted of regimental medical officers and of three field ambulances. The Director-General accompanied the expedition as Director of Medical Services, and Colonel Chas. Ryan, the Principal Medical Officer of the State of Victoria, accompanied the expedition as A.D.M.S. on the staff of General Bridges, the Commander of the Division. Colonel Fetherston took General Williams's place as Acting Director-General of Medical Services, and Colonel Cuscaden the place of Colonel Ryan as Principal Medical Officer of the State of Victoria.

The expedition left in October, a considerable delay having taken place owing to the necessity of finding suitable convoy, a number of German cruisers being still afloat and active. It reached Egypt without serious mishap in December, and at once encamped near the Pyramids at Mena.

There were some difficulties in transit. There was a most extensive outbreak of ptomaine poisoning on one ship, and measles, bronchitis, and pneumonia were much in evidence. The mortality was, however, small. The division on arrival settled down to hard training.

At once difficulties caused by the absence of Lines of Communication Medical Units became obvious. The amount of sickness surprised those who had not profited by previous experience. To meet the difficulty Mena House Hotel was improvised as a hospital and staffed by regimental and field ambulance officers.

At this stage, however, we can leave the division and return to the further development of medical necessities in Australia.

Steps were at once taken in Australia to raise a second division, and subsequently a third and other divisions in the same manner as the preceding. As time passed on, the unsuitability of some of the camps and the lack of medical military knowledge told their tale, and a number of serious outbreaks of disease took place. It is impossible to give accurate statistical evidence, but the Australian public seems to have been shocked that young, healthy, and well-fed men should in camp life have been so seriously damaged and destroyed. The causes as usual were measles, bronchitis, pneumonia, tonsillitis, and later on a serious outbreak of infective cerebro-spinal meningitis which was stamped out with difficulty and took toll (inter alia) in the shape of the lives of three medical men. The sanitation of the Broadmeadows Camp near Melbourne was not such as to provoke respect or admiration. The camp was ultimately regarded as unsuitable, and moved to Seymour, pending the necessary improvements.

It is instructive to note in passing that the Australian public received a shock when they were first informed of the amount of disease among the troops in Egypt. Yet it was apparently nothing like so great as that which existed in Australia, where the usual death-rate is so low. And yet, had the Service really profited by the lessons of the Russo-Japanese war, much of the trouble might have been avoided. The truth of course is that camp life, except under rigorous discipline as regards hygiene, and the loyal observance of that discipline by each soldier, is much more dangerous than the great majority of people seem to imagine. The benefit of the open-air life and of exercise is counteracted by the chances of infection due to crowding, defective tent ventilation, the absence of the toothbrush, and other causes.

In September, however, the Imperial Government notified the Australian Government that Lines of Communication Medical Units were required, and for the first time the majority of members of the Australian Army Medical Corps became aware of the nature of Lines of Communication Medical Units. The Government decided to equip and staff a Casualty Clearing Station, then called the Clearing Hospital, two Stationary Hospitals (200 beds each), and two Base Hospitals (each 520 beds). They were organised on the R.A.M.C. pattern, and the total staff required was approximately eighty medical officers. Even at this juncture the matter was not taken very seriously, and there was some doubt as to the nature of the response. The Director of Medical Services was anxious that the base hospitals should be commanded and staffed by men of weight and experience, and accordingly a number of the senior medical consultants in the Australian cities decided to volunteer. The example was infectious and there were over-applications for the positions.

The First Casualty Clearing Station was to a great extent raised and equipped in Tasmania. The First Stationary Hospital was raised and equipped in South Australia, the Second Stationary Hospital in Western Australia, and the Second General Hospital in New South Wales. An exception to this sound territorial arrangement was, however, made in the case of the First Australian General Hospital – an exception which proved unfortunate. The commanding officer, a senior lieutenant-colonel, was resident in South Australia. The hospital itself was recruited from Queensland, but as the Queensland medical profession was hardly strong enough to supply the whole of the medical personnel, most of the consultants, including all the lieutenant-colonels, were recruited in Victoria. Now Brisbane, the capital of Queensland, is some 1,200 miles by rail from Melbourne, and Melbourne about 400 miles by rail from Adelaide, the capital of South Australia. The result of these arrangements was that the captains and some of the majors were recruited in Queensland, together with the bulk of the rank and file and many of the nurses; whilst most of the senior medical officers, the matron, and a number of nurses were recruited in Melbourne, and the commanding officer (Lt. – Colonel Ramsay Smith) from South Australia. He brought with him some seven or eight clerks and orderlies. Furthermore a number of medical students and educated men joined in Melbourne. The bulk of the staff was, however, based in Queensland. This arrangement led to untold difficulties in the way of recruiting, and it is remarkable that the result should have been as satisfactory as it was. The equipment was provided partly from Melbourne, partly from Brisbane, and partly from South Australia. As the commanding officer was in South Australia, as the registrar and secretary was in Melbourne, and as the orderly officer was in Brisbane, some idea of the difficulties can well be imagined – particularly when it is remembered that with the exception of the commanding officer and a few officers, the members of the staff had no experience whatsoever of military matters. Nevertheless an earnest effort was made to secure the necessary equipment and personnel. In Melbourne great trouble was taken to secure as many medical students and educated men as could possibly be obtained.

On the whole the response to the call was more than satisfactory, and Australian people were of the opinion that a stronger staff could not have been secured.

It was at first intimated that specialists were not required, but ultimately after discussion the Government agreed to find the salary of one specialist. Consequently a radiographer was appointed with the rank of Major, and another officer was appointed oculist to the hospital with the rank of honorary Major. Subsequently he was appointed as secretary and registrar in addition, but without salary or allowances.

The equipment of the hospital was on the R.A.M.C. pattern, and was supposed to be complete. Furthermore, the Australian branch of the British Red Cross Society set aside for the use of the hospital one hundred cubic tons of Red Cross goods which were specially prepared and labelled at Government House, Melbourne.

CHAPTER II

THE VOYAGE OF THE "KYARRA" – LACK OF ADEQUATE PREPARATION – DIFFICULTIES OF ORGANISATION – PTOMAINE POISONING.

CHAPTER IIThe mode of conveyance of the hospitals to the front next engaged the attention of the authorities, and negotiations were entered into with various steamship companies. It was desirable that the hospitals should be conveyed under the protection of the regulations of the Geneva Convention.

After some negotiation and the rejection of larger and more suitable steamers, a coastal steamer, the Kyarra, was selected and was fitted to carry the hospital staff and equipment. The steamer is of about 7,000 tons burden. There were on board approximately 83 medical officers, 180 nurses, and about 500 rank and file, or a total of nearly 800 souls. The cargo space was supposed to be ample, and 100 tons of space were promised for the Red Cross stores.

When ready, the Kyarra proceeded to Brisbane and embarked a portion of the First Australian General Hospital. She then proceeded to Sydney, embarked the Second Australian General Hospital with its stores, equipment, and Red Cross goods, and then left for Melbourne, where she was to embark the remainder of the First Australian General Hospital, the First Stationary Hospital, and the Casualty Clearing Station.

On arrival at Melbourne, however, it was found that she was carrying ordinary cargo, that she was not lighted as required by the rules of the Convention, and that she was already fully loaded. Consequently the whole of the cargo was taken out of her, the ordinary cargo was removed, and she was reloaded. It was found, however, that there was no room for the Red Cross goods belonging to the First Australian General Hospital. Furthermore, a portion of the equipment which subsequently turned out to be invaluable, namely 130 extra beds donated to the hospital by a firm in Adelaide, was nearly left behind. It was only by the exercise of personal pressure that space was found for this valuable addition at the last minute. The importance of this donation will be mentioned later in the story.

Finally, after many delays, the Kyarra left Melbourne on December 5 amidst the goodwill and the blessings of the people, and made her way to Fremantle, there to embark the Second Australian Stationary Hospital and its equipment. She finally left Fremantle with this additional hospital, and made her way across the Indian Ocean.

Lieut. – Col. Martin, Commanding Officer of the No. 2 Australian General Hospital, was promoted to the rank of Colonel for the voyage only. He was promoted for the purpose of placing him in command of the troopship.

The voyage of the Kyarra involved calls at Colombo, Aden, Suez, Port Said, and Alexandria. Those on board believed in the first instance they were proceeding to France, and when they arrived at Alexandria, and found they were all destined for Egypt, many expressed feelings of keen disappointment on the ground that they would have no work to do. They were soon, however, to be undeceived.

The voyage itself does not call for lengthy comment. The ship was unsuitable for the purpose for which she had been chartered. She was small, overcrowded, and not as clean or sanitary as she might have been. Her speed seemed to decrease, and was scarcely respectable at any time; there were apparently breakdowns of the engines; and the food supplied to the officers and nurses was not infrequently inferior in quality and in preparation. In consequence an outbreak of ptomaine poisoning took place, and twenty-two officers and others were infected, two of them seriously.

The arrangements at the men's canteen had not been fully thought out, and in the Tropics it was not possible to obtain fruit of any description. Fresh or tinned fruits were not kept in stock. There was some tinned meat and fish, but the men could obtain nothing to drink except a mixture made from Colombo limes and water.

There was a certain amount of illness apart from ptomaine poisoning, and amongst the cases treated were bronchitis, influenza, tonsillitis, and eye disease. Five cases reacted severely to anti-typhoid inoculation, and required rest in hospital.

On the whole, officers, nurses, and men took the voyage seriously, and did their best to learn something of their work. The officers were drilled, the nurses gave lessons to the orderlies, and systematic lectures were given by the officers. An electric lantern had been provided by the O.C., and lantern lectures were given regularly during the voyage.

The quarters provided in the fore part of the ship for the men were certainly insanitary, and to an extent dangerous. Towards the end of the voyage many cases of rotten potatoes were thrown overboard, having been removed from beneath the quarters occupied by the men. With Red Cross aid, however, provided by the Queensland branch, fans had been installed, and an attempt made to render these quarters more sanitary and habitable. A portion of the deck could not be used because of leaky engines, and neither request nor remonstrance enabled those concerned to get these leaks stopped.

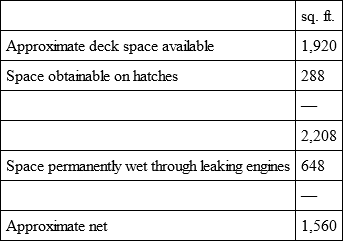

The following measurements show what trouble so simple a fault can cause. In the tropics the wet portion of the deck could not of course be used for sleeping purposes.

Approximate Deck Space Available for No. 1General and No. 2 Stationary Hospitalson Fore Deck

As the number of men occupying these quarters (including sergeants and warrant officers) was about 300, the space available approximated 5 sq. ft. per man.

Notwithstanding these conditions, the usual peculiarity of Anglo-Saxon human nature showed itself when at the end of the voyage the officers were required to sign the necessary certificates stating that the catering had been satisfactory. Only three refused to sign; the remainder signed, mostly with qualifications.

The manner in which the average Australian makes light of his misfortunes was strikingly illustrated on one occasion. A long, mournful procession of privates slowly walked around the deck. In front, with bowed head, was a soldier in clerical garb, an open book in his hand. Immediately behind him were four solemn pall-bearers, carrying the day's meat ration, which is stated to have been "very dead." Apparently the entire ship's company acted as mourners. The procession wended its way to the stern, where an appropriate burial service was read; the ship's bugler sounded the "last post," and the remains were committed to the deep. Needless to say the usual formality of stopping the ship during the burial service was not observed on this occasion. An attempt to repeat the performance was fortunately stopped by those in authority, and all subsequent "burials" were strictly unceremonious.

Those who go to war must expect to rough it, but on a peaceful ocean, secure from the enemy, and in a modern passenger ship, it should be possible to provide food which does not imperil those who consume it, and also to ensure reasonable comfort.

With reference to the defects of the ship it should be said that when the Kyarra was chartered Australians had not realised the colossal nature of the war, and had not begun to think on a large scale, and those responsible had neither tradition nor experience to guide them. Furthermore the commander and officers of the Kyarra courteously did their best, but it was evident they understood the difficulty of transforming a coastal steamer into a Hospital Transport.

The Geneva Convention does not seem to be fully understood, and experience shows what complicated conditions arise, and how easy it is to commit an unintentional breach of the Regulations. But in war there can be no excuses.

CHAPTER III

ARRIVAL AND SETTLEMENT IN EGYPT – DISPOSAL OF THE HOSPITAL UNITS – TREATMENT OF CAMP CASES – THE ACQUISITION OF MANY BUILDINGS – WHERE THE THANKS OF AUSTRALIA ARE DUE.

CHAPTER IIIOn arrival at Alexandria, there seemed to be no great hurry in disembarking, and many of the older medical officers were fully persuaded that the units were not wanted in France; that there was very little to do in Egypt; and that if their services were not required it would be fairer to inform them of the fact, and let them go home again. They were soon to be undeceived. A message was received asking the O.C.s of the various units to visit Cairo, where they waited on Surgeon-General Ford, Director of Medical Services to the Force in Egypt. They were informed that there was more than enough work for all these Lines of Communication Medical Units in Egypt.

The First Australian General Hospital was to be placed in the Heliopolis Palace Hotel at Heliopolis. The Second Australian General Hospital was to take over Mena House and release the regimental medical officers and officers of the Field Ambulances from the hospital work they were doing. The First Stationary Hospital was to be placed with the military camp at Maadi, and the Second Australian Stationary Hospital was to go into camp at Mena and undertake the treatment of cases of venereal diseases. The First Casualty Station was temporarily lodged in Heliopolis, and then sent to Port Said to form a small hospital there in view of the imminent fighting on the Canal. These dispositions were made as soon as possible.

It should be noted at this juncture that the bulk of the Australian Forces, namely the First Division, was camped at Mena. A certain quantity of Light Horse was encamped at Maadi, whilst the Second Division, composed chiefly of New Zealanders, was encamped near Heliopolis. New Zealand had not provided any Lines of Communication Units, but her sick had been accommodated at the British Military Hospital, Citadel, Cairo, and also at the Egyptian Army Hospital, Abbassia.